полная версия

полная версияSpain

VALENCIA includes the three provinces of Castellon de la Plana, Valencia, and Alicante, all three lying along the Mediterranean, and facing east and southwards from the mighty buttress sierras which form the eastern wall of the great central plateau. It is in these provinces that we gradually pass from the Mediterranean climate to the "Tierra caliente," the warm lands and African products of south-eastern Spain. Here too we meet with the finest Roman remains; and Moorish architecture begins to form a prominent feature in the characteristics of each city. The speech is still a dialect of the Provençal, and the fiery Provençal nature is still apparent in the political history of the cities of Valencia. The hill-sides, bare of trees, are covered either with the esparto grass or with strongly aromatic herbs and shrubs. The rainfall gradually lessens; the streams all assume a torrential character, nearly dry in summer, swollen with rapid floods in winter; but they are greatly utilized for irrigation. By this means are formed the "huertas," gardens, and "vegas," plains, oases of beauty and fertility lying in the bosom of the barren hills, which serve as frames to pictures as valuable for their productiveness as they are enchanting in their beauty. The chief towns in the province of Castellon are Castellon de la Plana (23,000), Vinaroz (9000), Villareal (8000), both near the Mediterranean; Segorbe on the Palancia, and numerous smaller towns in the interior. Benicarlo and Vinaroz, on the coast to the north of the province, are noted for their excellent red wines, quantities of which are exported to France for mixing with inferior French vintages, whence they find their way to England as Rousillon or Bordeaux. Valencia, a city of 143,000 inhabitants, and with a fine artificial harbour called the "grao," is the third city in population in Spain; but its commerce is little more than that of Santander and Bilbao, cities only one fourth of its size. The value of British imports, chiefly of coal, cod-fish, guano, and petroleum, in 1878, was 136,450l., and of exports, chiefly of fruits to Britain, 524,984l. The "huerta" of Valencia, with its canals for irrigation, its "acequias," "norias," and other devices to draw the waters of the Guadalaviar, is one of the most successful examples in Spain of regulated application of water to agriculture. The quantity of water allotted to each property, the hour of opening or closing the sluices, are regulated according to laws and customs descended from Moorish times. So great is the drain upon the streams that the waters of some of the smaller rivers are entirely absorbed in the summer, and even of the Guadalaviar but little then reaches the sea. It is from the huerta of Valencia that the oranges come which form the delight of the population of Paris at the new year; hence are the raisins and the almonds and candied fruits equally dear to the British housekeeper. Rice is successfully cultivated on some of the lower grounds near the coast, and fruits and vegetables of every kind abound; but the Spaniards complain that they lack the richness and lusciousness of flavour belonging to those grown in other parts. "In Valencia," say they, "grass is like water, meat like grass, men like women, and the women worth nothing." The district was formerly noted for its silk-growing and stuffs of silk; also for the fine pottery known as Majolica ware from its carriers to the Italian ports, the sailors of Majorca and the Balearic Isles. It was also the earliest place of printing in Spain, and celebrated as a school of poetry and the arts; but nearly all this ancient fame is lost. To the south of Valencia is the large lake or lagoon of Albufera, the most extensive of the many lagoons along the Mediterranean coast, about nine miles long and twenty-seven miles round; it is full of fish, and frequented by wild fowls, and its varied inhabitants recall those of the Nile rather than those of any part of Europe. In the north of the province is Murviedro (7000), the ancient Saguntum, with its port almost entirely blocked up. Considerable remains of the older city still exist, with inscriptions in idioms yet unknown, and are a treasure to archæologists. The largest of the other cities are Alcira (13,000) on the Jucar, and Jativa (14,000). The southern coasts of Valencia and the neighbouring districts of Alicante abound in sites of picturesque beauty, and the position of many of the ruined monasteries, built generally on the hills with a distant prospect of the sea, can hardly be excelled.

Alicante, whose huertas and vegas with their appliances for irrigation rival those of Valencia, has but 34,000 inhabitants. Orihuela, in its rich wheat-growing district of never-failing harvest, has 21,000, and Alcoy 32,000. The smaller towns are numerous, and from the little ports in the north of the province, round Cape Nao, a good deal of coasting trade is done with the neighbouring Balearic Isles. From Denia, Tabea, and Altea, nearly 100,000 tons of raisins are shipped every year, chiefly for Great Britain. At Elche (20,000) is the celebrated forest of palms of which we have before spoken, and the leaves of which are sent to Rome for the ceremonies of Easter week. The number of the trees is gradually declining, as the produce hardly repays the great amount of labour required. In the church at Elche religious plays or mysteries are occasionally performed, with an enthusiasm and solemnity both of actors and spectators equal to that of the Passionspiel of Ober-Ammergau.

MURCIA contains the two provinces, Murcia and Albacete. The first faces the Mediterranean; the second, besides comprising the Sierras of Alcazar and Segura, climbs those boundary mountains, and advances far into the plateau of La Mancha, and thus contains within its limits the sources of the Guadiana as well as those of the Mundo and the Segura. Murcia, in its higher parts, is very thinly peopled, and in spite of the fertile plains in the lower course of the Segura and the Sangonera, and the rich mining district round Cartagena, has only two-thirds as many inhabitants to the square mile as Valencia. Murcia is perhaps the driest province of Spain, and the one in which the want of water is the most generally felt, yet it is in this province that the floods are the most pernicious and destructive. Year by year the irrigation works become less effective. Ancient dams broken down by the floods are not restored. Since 1856, however, a new source of wealth has been opened to this province by the export of the esparto grass, which grows on all the low hills, and which, in addition to its use in the country for numerous native fabrics, is now largely exported for paper-making. The export began only in 1856. In 1873 it had reached 67,000 tons for England alone; in 1875 the money value of the whole export was 400,000l., but it declined to 30,000l. in 1877, and 284,000l. in 1878, since which date it has gradually lessened. Murcia, the chief city, is an irrigated plain on the Segura, has a population of 91,000. It is one of the chief seats of silk cultivation in Spain. Lorca (52,000), on the Sangonera, offers another example of the extreme fertility that can be obtained by irrigation in a suitable climate. Cartagena (75,000), with its grand harbour and docks, is one of the three naval arsenals in Spain; but has greatly fallen from its ancient wealth and importance. Like Barcelona and Valencia it has distinguished itself by its extreme democratic and cantonalist opinions, and has revolted against the republic equally as against the monarchy. In its neighbourhood are some of the richest lead and silver mines in Spain, and which have been worked since Carthaginian and Roman times. The coal imported from England for smelting purposes amounts to 80,000 tons yearly. The tonnage of British vessels employed was over 200,000 in 1877. Along the coast are various lagoons and salt-lakes (salinas), where salt is made on a considerable scale; it is exported chiefly to the Baltic. The Barilla plant, for making soda, is also cultivated along the coast; and, of the plants in the salinas, it is computed that at least one-sixth of the species are African. Albacete (16,000), situated at the junction both of road and railway from Murcia and Valencia to Madrid, is chiefly celebrated for its trade in common cutlery. It is here that the large stabbing knives (navajas) are made, and for the use of which both Valencians and Murcians have an unenviable notoriety. On the plateau of this province (Albacete) are found (Salinas) salt-lakes formed by evaporation, the only examples of this kind in Western Europe. The only other town of any importance in the province is Almanza (9000), on the edge of the plateau before making the descent into Valencia. The numerous names compounded of "pozo," well, and "fuente," fountain, in this province, attest its arid character, where fresh water is scarce enough to make its presence a distinguishing mark to any spot.

ANDALUSIA embraces the whole of southern Spain from Murcia to the frontier of Portugal. Its seaboard includes both the Mediterranean and the Atlantic. In Cabo de Gata, 2°10' W., it has the extreme south-easterly point of Spain; and in Cabo de Tarifa, 36°2' N., the extreme southerly point, not only of Spain, but of Europe. One chain of its mountains, the Sierra de Nevada, contains the highest summits of the peninsula; and its river, the Guadalquiver, from Seville to the ocean is the only stream of real service for navigation in the whole of Spain. Its wines and olives, its grapes and oranges, and fruits of all kinds, are the finest, its horses and its cattle are the best, its bulls are the fiercest, of all Spain. The sites of its cities rival in their entrancing beauty those of any other European land; while, wanting though they may be in deeper qualities, its sons and daughters yield not in wit or attractive grace or beauty to those of any other race. The Moor has left a deeper mark here than elsewhere, even as he kept his favourite realm of Granada for centuries after he had lost the rest of Spain. And when the sun of Moorish glory set, it was from Andalusia that the vision of the New World rose upon astonished Europe. The year of the conquest of Granada (1492) was also that of the discovery of America. All things take an air of unwonted beauty and of picturesque grace in this land of sun and light; even the gipsy race, avoided and abhorred in other countries of Europe, at Granada, as at Moscow, becomes one of the attractions of the tourist. The province is not entirely of one type. It unites many kinds of beauty; even in Andalusia are "despoblados" and "destierros," dispeopled and deserted wastes, under Christian hands, but once fertile and inhabited under Moorish rule. Savage wildness and barrenness reign in its lofty mountain chains as much as softer beauty does in the "huertas" and "vegas." But from the minerals the one district is equally valuable as the other. The province possesses the richest mines, as well as the richest fruits and wines, of the whole of Spain. ANDALUSIA, is divided into the provinces of Almeria, Granada, Malaga, on the Mediterranean; Cadiz, Seville, Huelva, on the Atlantic coast; and Cordova and Jaen inland, along the upper waters of the Guadalquiver.

In Almeria (40,000) the flat-roofed houses are built round a central court, the "patio," wherein is often a fountain, and palm and vine for shade; while oranges, myrtles, passion-flowers, and other gay or odoriferous shrubs or flowers, add their colour and perfume. The type and the manners of the inhabitants tell us that we are already in the land of the Moors. Almeria has declined from what it was when one of the chief ports of transit between the Moors of Africa and their brethren of south-eastern Spain; but from the growing importance of the Spanish colony in Oran, its trade is now fast reviving. The exports are lead and silver ore from the mines of the neighbourhood, fruits of all kinds, and a little wine. The tonnage of British shipping employed at Almeria was, in 1875, 117,123 tons; 1876, 85,840 tons; 1877, 89,988 tons. The chief exports in 1877 were about 10,000 tons of esparto grass, 280,000 barrels of grapes, 10,000 tons of minerals, and nearly 10,000 of calamine. The sugar-cane is also grown here. The whole province is mountainous, covered with the spurs and offshoots of the mighty Sierra Nevada, the Sierras de Gador, de Filabres, de Cabrera, de Aljamilla, all which have their terminations in headlands which run into the Mediterranean. The basins of the rivers of the region are often cleft by these smaller ranges, and thus they receive their waters from both the northern and southern slopes of the Sierra Nevada. The only other towns of importance are Cuevas de Vera (20,000), and Velez-Rubio (13,000), in the north of the province on the road between Murcia and Granada, where some lead-mines have been lately opened. The ports, except Almeria, are all small; Dalias, on the confines of Granada, is noted for the magnificent grapes and raisins shipped there.

Granada (76,000) is one of the most celebrated spots of Europe, a city of enchantment and of romance. It is one of the few places of renown, the sight of which does not disappoint the traveller. The natural advantages of its position would be sufficient to mark it as a city of unusual beauty, were there no masterpieces of art and of architecture, or storied memories, connected with it. It is situated in an upland valley, at an elevation of 2200 feet above the sea level—sufficiently high in that climate to prevent the summer's heat from being oppressively exhausting, and not too high to hinder the choicest semi-tropical fruits and flowers from growing in the open air—surrounded, yet not too closely, by mountain ranges, of which those to the east are the very highest in Spain—Mulhacen (11,700), Alcazaba (11,600), and Veleta (11,400). The ice and snow on their summits not only cool the hot winds which blow over them from Africa, but provide the means of making the iced water which is the Spaniard's greatest luxury. Its climate is second in its equable range only to that of its coast towns, Motril and Malaga. It is watered by the united streams of the Darro and the Jenil, which meet within the city, both hurrying from their mountain home to join the Guadalquiver between Cordova and Seville; and with their fertilizing waters dispersed in irrigation they make the "Vega," or plain, of Granada one of the noted gardens of the world. Granada is worth all the praise that has been sung or written of it. On an isolated hill to the east, cut off from the town and from the Generalife by the ravine through which the Darro flows, and enclosed with a wall flanked by twelve towers, stands the celebrated group of buildings known by the name of the Alhambra, perhaps the fairest palace and fortress at once ever inhabited by a Moslem monarch. Almost unrivalled in the beauty of its site, it outstrips all rivals in the beauty of its Arab architecture. The mosque of Cordova is grander, and the tombs of the Caliphs at Cairo may be in a purer style, but they lack the variety and richness of these diverse buildings. The Alhambra hill is to Arabic what the Acropolis of Athens was to Hellenic art; only to the attractions of the plastic arts were added in the case of the Alhambra the triumphs of the gardener's skill. Shrubs and flowers delighted the eyes with colour, or gratified the sense of smell with sweetest odours, while water, skilfully conducted from the neighbouring hills, purled among the beds, or leaped in fountains, or filled the baths with purest streams. Thus every sense and taste was gratified, and Granada was indeed an earthly paradise to the Moor. Even in its decay, and seen in fragments only, it is one of the world's wonders, a treasure and delight to pilgrims of art from every land. But we must not waste our space in detailing the beauties of Granada; its trade, sadly diminished from what it was formerly, is chiefly in fruits and silk and leather stuffs. Next to Granada, the chief city in the province is Loja (15,000), near the Jenil, and the little port of Motril (13,500), sheltered under the highest summits of the Sierra Nevada, is said to possess the most equable climate of the Spanish Mediterranean ports. It is here, in the extensive alluvial plain stretching from Motril to the sea, that the sugar-cane is most extensively cultivated, producing in 1877, 113,636 tons of cane. Far inland, and separated from Motril by the mountain mass, is Baza (13,500). The mineral riches of the Sierra Nevada have never been adequately explored; from specimens used in the construction of Granada, it must possess marbles of rare beauty; metals, too, abound, but few of its mines are worked. In picturesque beauty, when seen near at hand, these mountains are not nearly equal to the Pyrenees and to many minor chains; with rounded summits, they are bare and denuded of wood, and are entirely without the glacier forms, and the lakes and rushing streams, which delight us in the Alps.

Malaga.—The greater part of this province lies in an amphitheatre of mountains, stretching from the Sierra de Almijarras on the east to those of De la Nieve and of Ronda to the west. It faces the full southern sun, but is watered and irrigated by torrential streams from the mountains, at times almost dry, at others, as in December, 1880, rushing down in most destructive floods. The city, with over 110,000 inhabitants, boasts not only the finest climate in Spain, on which account it is greatly frequented by invalids in the winter, but its commerce is second in value to that of Barcelona. Its wealth and exports are almost wholly agricultural, consisting of luscious wines—which, however, have a greater reputation on the continent than in England—oil, fruits, and especially dried raisins; oranges, olives, figs, sugar, and sweet potatoes. Bananas, and all other tropical and semi-tropical products of Spain are here found in perfection. Upwards of 2,000,000 boxes of raisins, 3,000,000 gallons of oil, and 1,100,100 gallons of wine, besides other fruits, esparto grass, and minerals (chiefly lead), are annually exported. The tonnage of British vessels in 1878 was about 158,000 tons. It has been a city and port from great antiquity; but though a favourite residence of the Moors, they have left fewer remains here than at Granada, Seville, Cordova, Toledo, and many a place of lesser note. Antequerra (25,000), on the Guadaljorce, on the northern slope of the sierras, guards the defile leading to Malaga, and was formerly of great military importance. The Cueva del Menjal, in the neighbourhood, is a fine dolmen. Ronda (20,000), the chief town of the sierra of the same name, is remarkable for its position on both sides of an enormous fissure (el Tajo) from 300 to 600 feet deep, and which is spanned by a magnificent bridge, constructed by the architect Archidone, in 1761. Velez Malaga (24,000) is a small sheltered port to the east of Malaga, with a trade in fruits and wines.

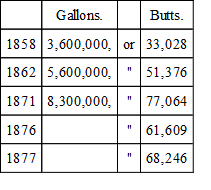

Cadiz, the most southerly province of Spain, includes the capes of Trafalgar and Tarifa, and the Punta de Europa, or the English Rock of Gibraltar. This province is also the principal seat of the great sherry trade. The town (65,000) and port have greatly fallen from their former importance, when Spain possessed nearly all the Americas south of California, and but for the Transatlantic steamers to Cuba and the West Indies, and to the Philippine Islands in the East Indies, would probably decline still more. The application of steam, allowing ocean vessels to ascend the Guadalquiver rapidly to Seville, has arrested there a great deal of the produce which formerly came to Cadiz, but which is now shipped at the former town. The total tonnage of the port is now about 800,000; the imports over 2,000,000l., of which about one-sixth is British; but of the exports, which are about the same in value, fully two-thirds go to Great Britain. Cadiz itself is undoubtedly one of the oldest ports of Western Europe, and is situated on a narrow promontory, formed into an island by the channel of San Pedro. Unlike most of the southern cities of Spain, its houses are of great height and of several stories, the contracted space of its site having occasioned this architectural modification. The city is excellently supplied with fish; the market is noted both for the quantity and the variety of its supply, which amounts to nearly 900 tons annually. Round the Bay of Cadiz are situated towns and harbours of considerable size, whose united commerce is almost equal to that of Cadiz itself. Of these, Puerto de St. Maria (22,000), on the northern side of the bay, is the great harbour for the shipment of sherry wines. Immense quantities of salt are made, chiefly for exportation, in the Salinas between Puerto Real and San Fernando (26,000), and Chiclana (20,000), on the San Pedro canal, which cuts off the Isle of Leon from the mainland. The export of wine from the whole Bay was, in

Xeres de la Frontera (64,000), situated about thirty miles from Cadiz, surrounded by vineyards, is a city of Bodegas, or wine-cellars, the principal of which, as well as of the vineyards, are in the hands of foreigners. It is one of the busiest of Spanish commercial towns, and, like Barcelona, is on that account less peculiarly Spanish than many others. The exportation of sherry wines from the district, and those shipped at Port St. Mary, amounted, in 1873, to 98,924 butts; 1874, 65,365 butts; from Jerez alone, in 1875, 43,727 butts; 1876, 42,272 butts; 1877, 41,660 butts; 87 per cent, of which goes to Great Britain and her colonies. The decrease in later years is probably caused by the greater amount of lighter French wines now consumed in England. San Lucar de Barrameda (22,000), at the mouth of the Guadalquiver, is noted for its winter-gardens, which are said to date from Moorish times, and which supply Cadiz and Seville with their earliest fruits and vegetables. From its vineyards, too, comes the stomachic Manzanilla sherry, flavoured with the wild camomile, which grows abundantly in its vineyards. Arcos (12,000), on the Guadalete, is the only other Spanish town of importance in the province; but to the south lies the isolated rock and fortress of Gibraltar (25,000), captured by the Earl of Peterborough in 1704. Though held only as an English garrison (5000), and made almost impregnable as a fortress, it is yet of considerable commerce from its position as a port of call for vessels passing the Straits of Gibraltar, and also from its contraband trade with Spain, which is a source of constant irritation between the two nations. In natural history, it is remarkable for its apes (macacus inuus), as the only spot in Europe where any species of monkey lives, and it is doubtful whether even these would survive without the aid of occasional importations from Morocco.

Seville is the typical province of Andalusia, and its city of 133,000 ranks fourth in population of the cities of Spain. The Moors have left deeper outward traces at Granada, but here they have fused more thoroughly with the population, and have given it the Oriental grace and culture which is lacking in the former place; their wit belongs to themselves. Seville is peculiarly the home of Spanish art; the greatest of her painters, Murillo and Velasquez, were born there, and Zurbaran painted his best pieces to adorn her walls. Her writers are scarcely less noted. The most celebrated novelist of modern Spain, Cecilia Bohl de Faber (Fernan Caballero), had her home there. There Amador de los Rios composed his chief works. The Becquers—both the painter and the novelist—were born there. It is a city of predilection for all of artistic tastes. The Giralda, a tower of Moorish architecture, rivals, if it does not surpass, in its exquisite proportions the campanille of Italian art. The Alcazar is a home of beauty. The patios, or inner courts, of many of the houses have remains of Moorish decoration. The Cathedral shows that Christian lags not far behind Moslem architecture. But Seville, on the Guadalquiver, is not a mere city of pleasure. Like Paris, its gay exterior contains a great deal of real work and commerce within. Since the invention of steam, allowing sea-going vessels to breast with ease the current of the Guadalquiver, it has drawn to itself a great deal of the traffic which formerly passed through the harbours of the Bay of Cadiz. The tonnage of its shipping amounts to about 120,000 tons, and the value of its imports to over 2,000,000l., and of its exports to 1,750,000l., one-half of which belongs to Great Britain. Among its manufactories, one of porcelain, carried on by a British company, but employing Spanish methods, is celebrated; and its tobacco manufactory, with its 1000 women workers, is the largest government establishment of the kind in Spain. The city long enjoyed almost a monopoly of West Indian and of Manilla productions; the wealth brought by the galleons was deposited here, and here are still preserved the "Archivos de las Indias." It possesses both a university and a mint. The lower part of the Guadalquiver runs through marshy lands, which in places present almost impenetrable jungles. In these are bred the bulls which supply the bull-fights with their victims, and which make Seville the great school of tauromachia in Spain. The finest Andalusian horses are also produced in this province, and the wines, though not equal to those of the neighbouring provinces of Cadiz and Cordova, are still highly esteemed. Besides Seville, the chief towns are Ecija (24,000) on the Jenil, a place of large trade; Carmona (18,000); Ossuna (16,000). Utrera, Lebriga, and Marchena would be considerable towns in other provinces, but we can only indicate them here. From the absence of mountains Seville has not the mineral wealth of some other provinces, but coal is worked at Villanueva del Rio, and the copper-mines at Arnalcollar yield 20,000 tons of ore; other outlying deposits of the Huelva beds are found in this province, and a great part of the lead from the Linares mines is shipped here.