полная версия

полная версияSpain

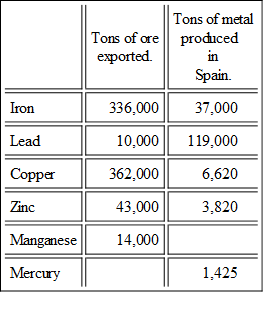

The quantity of mineral contained in the rocks of Spain is no less remarkable than the exceptional variety of its distribution; but owing to a series of adverse circumstances, the industrial production affords a most inadequate idea of the capabilities of the mines, if developed by a fair amount of capital and skill. The following figures, showing the production in 1875, are derived from the last official reports issued by the Spanish Government, and are certainly below the truth:—

These figures do not include the bar iron produced directly from ore in Spain, nor 160 tons of argentiferous copper ore, 89 tons of cobalt ore, and 440 tons of nickel ore. The silver extracted in Spain amounted to more than 16,000 lbs. troy, while four times that amount was contained in exported argentiferous lead. The coal extracted amounted to 666,000 tons, lignite above 27,000, sulphur above 3000, and phosphorite above 12,000 tons. The year 1875 was, however, peculiarly unfavourable to Spanish mining, and the working of the Bilbao mines, which now produce nearly 2,000,000 tons yearly of excellent iron ore, was then practically suspended by the Carlist war. All disadvantages cannot, however, arrest the steady increase of mineral production in Spain, although under more normal political circumstances the above figures would have been greatly exceeded.

The chief coal district is that of Oviedo, Palencia, Leon, and Santander. The coal-field of Oviedo, occupying an extent of 230 square miles, and including a large number of workable beds, is of excellent quality, but as yet little developed, owing to high railway tariffs, bad condition of ports, traditional prejudices, want of skill and capital, and of a local market for inferior qualities. These obstacles will probably soon be overcome, and the development of the associated iron ores afford an important field of enterprise.

The coal-field of Palencia, a continuation of that of Oviedo, is in course of development by the Northern Railway Company. Smaller coal-fields of great local importance exist in the provinces of Cordova, Seville, Gerona, Burgos, Cuenca, Guadalajara, and Ciudad Real; that of Gerona, although of small extent and very friable quality, has already occasioned the construction of a railway of considerable length. Iron is mainly obtained from Biscay, Oviedo, Murcia, and Almeria, but is abundant in other provinces. Lead is worked chiefly in Murcia, Jaen, Almeria, Badajoz, and Ciudad Real; the presence of antimony or of a predominating admixture of blende is very common, but Spain is on the whole the most important lead-producing country in Europe. Copper is obtained mainly from the Rio Tinto mines and others in Huelva; also from Seville, Palencia, Almeria, and Santander; but many other districts contain veins yielding more or less of copper ore. Zinc has been chiefly procured from superficial pockets of calamine in Santander and the neighbouring districts; but in the form of blende it is widely distributed in association with lead. Silver ores are worked in Almeria and Guadalajara. The immense impregnation of cinnabar of Almaden, in Ciudad Real, affords nearly all the mercury, but a little is obtained from other mines in the same province and in Oviedo, Granada, and Almeria. Manganese is obtained from Huelva, Oviedo, Teruel, Almeria, Murcia, and Zamora. Nickel ore is worked in Malaga; cobalt in Oviedo and Castellon. Tin occurs in a number of small veins in Galicia; and in the rocks of Salamanca, Murcia, and Almeria, as well as in diluvial gravels. The Spanish side of the Pyrenees contains numerous veins of argentiferous lead, many of copper, and some of cobalt, nickel, argentiferous copper, pyrolusite, &c., few of which are worked. The lead-mines on the border between Catalonia and Aragon supplied the Carlists with ammunition during the late civil war. The fact that more than 12,000 concessions of mines already exist in Spain, while a large number of lapsed concessions may be found, affords a better idea of the mineral wealth of the country than the enumeration of the mines actually worked.

That such enormous mineral resources should have as yet yielded no greater results is easily explained. The Roman and Moorish workings, although traditionally of fabulous yield, are of small depth, owing to insufficient machinery for pumping. Till the present century, the working of mines was forbidden by the Spanish Government, with the object of favouring the development of the American colonies. The mining laws of 1825 and 1849, suddenly placing the acquirement of mines within the reach of every substantial peasant, produced a fever of speculation, and a recklessness in the application of unskilled labour, which naturally conduced to the discouragement of mining enterprise, while the recurring civil wars excluded foreign capital and skill. Spaniards have a mania for erecting smelting-works on the mines, a practice occasionally justified by difficulties of transport, but which has caused much loss of capital through inherent difficulties and want of metallurgical skill. Endless litigation, arising from the defects of the first mining laws, and the inexperience of the surveying engineers, contributed to ruin the small capitalists who had attempted to work the mines. Foreign capital is now the chief requirement. The existing mining law, greatly improved since 1868, is the simplest in Europe; the expense of a concession is almost nominal, and the royalties on ore are extremely moderate. Large mining adventures in Spain rapidly develope industrial conditions and profoundly affect the habits of the population. Even in times of civil war a modus vivendi between the conflicting parties can be more easily secured than might be expected. The development of means of transport, already considerable before the last Carlist war, is being seriously resumed under the present Government. The Spanish peasantry, when suitably treated, will be found a fair-dealing, intelligent, and industrious class. It must, however, be remembered that in the peculiar physical, political, municipal, and fiscal conditions of Spain, no mining enterprise can safely be undertaken without thorough investigation of all the external circumstances, claims, and prospects concerned; since more mining speculations have failed from inattention to such matters than from any disappointment as regards the quality or quantity of ore. P. W. S. M.

CHAPTER IV.

ETHNOLOGY, LANGUAGE, AND POPULATION

ON the first glance at a map of Spain and Portugal we are apt to think that few countries could have so well-defined a frontier as that formed by the Pyrenees, the Mediterranean, and the Atlantic. In so compact a country, and one so distinct and so shut off from the rest of Europe, we should expect to find a more unmixed and a more homogeneous population than in any of those states whose frontiers are more open and conventional. But such is very far from being the case. Even at the present time the Pyrenees are no boundary throughout their whole course, either as to race or language. The Basque overlaps them at one end, and the Provençal at the other. Moreover, they have been a political boundary throughout their whole length only since the middle of the seventeenth century. Navarre was united to the Spanish crown in 1515, and Rousillon to France only in 1659. Ecclesiastically, both the dioceses of Bayonne and of Narbonne advanced far into Spain. So far from the population of Spain being unmixed and pure, the contrary is far nearer the truth. As Senor Tubino has well observed, from its position at the south-western angle of Europe, and the most westerly of Mediterranean lands, beyond which lay only the impassable ocean, it must early have become a very eddy of nations, where all the tribes and races who have successively held command of the Mediterranean must necessarily have halted, over which and in which all invaders who have crossed the Pyrenees from Northern Europe, or have passed the Straits of Gibraltar from Africa, must have surged in almost ceaseless conflict. To think of Spain as ever having been at any given time occupied solely by any single race or people is to lose the clue to her whole history. Of this not only the social and political condition of the country, but the toponymy and nomenclature of her map afford decisive proof.

We first hear of Spain in history about the sixth century before Christ, as then inhabited by the "Iberi" and "Kelt-Iberi," with here and there colonies of more unmingled Kelts. It is more than probable that both of these races succeeded anterior ones, the existence of which we trace only through the remains of præhistoric archæology, in the flint, stone, and bronze instruments, similar to those found elsewhere in Europe; these were also probably followed by races whose remains we find in the sculptors of the so-called "Toros" (bulls) of Guisando, and in the builders of the Megalithic monuments, the dolmens, menhirs, and circles which are found from Algeria to the Orkneys. For all purposes of history we must take the "Iberi" and the "Kelts," with their mixed tribes, as our starting-point. These we find scattered in much confusion throughout the Peninsula. Either the tribes were constantly shifting their ground, owing to petty wars and tribal dissensions or to unknown economic conditions, or the successive Greek and Latin writers from whom we get our information have not themselves been clear as to the distinction of these races. Speaking loosely, we may say that the more purely Keltic tribes held their ground in the north-west and west, in Galicia and Portugal, with a few scattered colonies further south. Andalusia, parts of the centre, the north and north-east were inhabited by the "Iberi;" while the Kelt-Iberian tribes lay chiefly in the centre and on the eastward slope. Both of these great races have left clear traces on the maps of ancient Spain. There can be no reasonable doubt that the "Illiberris" which we find in classical maps is a transcription of the Basque "Iriberri," which we still find in the French Basque country and in Navarre, meaning "New-Town," or more exactly, "Town-new;" that when the Romans called a town which they built in Galicia "Iria-Flavia," in honour of their then empress, they really used the Basque word "Iri," a town or city, just as the colonists of the United States and Canada used the French "ville" or English "town," and named a new city Louisville, Charleston, Georgetown, in the North American colonies. So, too, any one who compares the name "Peña," given to mountains and mountain-chains on the map of Spain, together with the river names, "Tamaris," "Deva," and the town and district of "Britonia" or "Britannia" in the north-west, can hardly doubt that these names were given by the same Keltic race who have left us so many "Pens" and "Bens" in Northern Britain, who gave the names "Tamar" and "Dee" to Devonshire and Cheshire streams, and called our own island Britannia, and themselves Britons. Which of these races is the older? the Iberi, i.e. Basque, or the Keltic? How can we decide this? Language is a deceitful tool as regards race. A people may utterly forget their original language, and adopt that of their conquerors or of some superior race with whom they have come in contact. Of this we have not only numerous examples in the past, as in the Latin and romance tongues superseding many a more ancient idiom, but we can see the same change actually going on in our colonies and dependencies in our own day. Still there is a certain rough chronology in language. A monosyllabic language we may presume, in default of evidence to the contrary, to have preceded one whose characteristic is agglutination; and again, a language which agglutinates or incorporates its members is presumably prior to an inflexional or analytic one. Now the Basque, the modern form of some one of those tongues which the Greeks and Romans called Iberian, belongs to the second of these classes, and the Keltic to the third. Another mode of investigating the antiquity of a language is to study the original names of the most necessary objects of daily life, and see if they can reveal to us anything about the state of civilization of those who used them before the language took a literary shape or any books were written in it. A language in which we find all the words expressing articles of greater civilization to be borrowed from other tongues we may presumably deem older than the languages from which it has borrowed them. Now in the Basque, Escuara, the undoubtedly native words for cutting instruments seem all to have their root from words signifying stone, or rock, and all such words which imply the use of metal seem to be borrowed. The language as it were represents the "stone" age, before the use of metals was known. It is also singularly poor in collective and general terms; thus, while many of the names for separate kinds of trees are native, the most common collective term arbola, "the tree," is clearly borrowed from the Latin. Although the arguments from anthropology, the form of the skull, &c., as compared with other races, are of still more dubious value than those derived from language, yet they all tend to the same conclusion. We may then hold from these convergent lines of reasoning, at least as a provisional hypothesis, that the Iberian or Basque race is older in Spain than the Keltic, and consequently that in the representatives of the former we have the remains of the oldest historical people of which we have any record in the country.

We said above that, from its geographical position, the Peninsula would necessarily be the final-halting-place in ancient times of all the masters of the Mediterranean as they pushed westward. There we should find their farthest outposts. Thus in Spain we have, at first dimly seen, successive colonies of Egyptians, Phœnicians, and Greeks. There it was that Carthaginians and Romans met to dispute the supremacy of the Mediterranean and of the civilized world. When, after a long occupation, during which it Latinized Spain more completely than any other country except Italy, the Roman Empire fell, successive waves of barbarian destroyers swept across the land, Sueves, Alans, Vandals, Visigoths, in wild confusion and internecine strife, wrecked the civilization which they could neither appreciate nor understand. The last of these races, the Visigoths, who ruled the longest, strove hard to found an empire from 450 to 710, but without success. The real power which held society together then, and which wrought what little order and law still existed, was the Church, and not the State. The Councils of the Church were the true legislative assemblies, and the real representatives of the people in those times. Yet, with all the power of the Church to uphold it, the Visigothic Empire remained so weak that it fell at the first shock of the Mohammedan Arabs. The Moors or Arabs landed in Spain in the year 711. In ten years they had conquered all of the Peninsula that they cared to hold; in eleven years more, 732, they had been defeated at Poictiers by Charles Martel, and had withdrawn for ever from France, except from the district of Narbonne. This rich province they held for many years, and it would seem to them to be more than an equivalent for the bare and humid mountains of Galicia and the Asturias, or the higher Pyrenees, which alone in the Peninsula were exempt from their sway. The Arabs and the Moors of Barbary are the last great race that has occupied Spain. Jews and a few Gipsies are the only peoples that have entered since. A few remnants of Berber tribes, isolated from their countrymen by the rapid advance of the Christian army in the tenth and eleventh centuries, like the Maragatos of Astorga, have remained in North-Western Spain, and doubtful remains of other peoples are found here and there, but none of these are in sufficient numbers to influence the nation as a whole. No country was more completely Romanized than Spain. In fact, after the Augustan age we might almost say that the best Latin writers were Spaniards born; Seneca, Quintilian, Lucian, and Martial were all natives of Spain. Hosius, the champion of Latin Christianity in the early part of the fourth century, was a Spaniard. The names of many of the towns are still Roman. Yet the Arabs have left almost a deeper mark upon the toponymy of the country. Look at the map of Spain, and we see, even up to the Pyrenees, how many Arabic names there are, especially of rivers and mountains, upon the map of Spain. Only in Galicia and the Asturias the Keltic and the Latin, in the Basque Provinces the Basque, and in Catalonia the Romance names have held their own. In all the rest the Roman names would have probably died away, but that the language of the Church was Latin, and preserved the Roman names of cities, monasteries, and shrines. Down even to the twelfth century it might seem doubtful which language would prevail, so many Arabs wrote in Spanish, and Spaniards in Arabic, or wrote Spanish in Arabic characters. The struggle was decided by the sword; the expulsion of the Arabs was also the expulsion of their tongue. Yet the Arabs have left far more traces on Spanish than Spanish has done on Arabic. The Spanish Jews, however, had forgotten their Semitic tongue, and to this day the sacred language of the Jews of the Balkan Peninsula, and of many of the Syrian Jews, even of those at Jerusalem, is not Hebrew but Spanish; their liturgical works are written in that tongue, and they use it always in the synagogue.

In spite, however, of all this mixture of races and of languages, Spain and the Spanish language has perhaps fewer dialects than any other European speech. From the Central Pyrenees to the Straits of Gibraltar only one dialect is used, the Spanish or Castilian, the purest and noblest of those which sprang from the decaying Latin. At the inner angle of the Bay of Biscay Basque is still spoken by a population of about 400,000 souls. The Galician dialect is far more closely allied to the Portuguese than to the Spanish, and should be considered as belonging to the former tongue. Between Galicia and the Basque Provinces are the many Patois, or Bables, of Asturia, which alone of the Romance tongues in the Peninsula have kept the three distinct genders, the masculine, feminine, and neuter terminations of the Latin adjective. The speech of Leon, too, may be classed as a separate dialect. In Catalonia, Valencia, and the Balearic Isles a Provençal or Romance dialect is spoken, the Lemosin as it was called in mediæval times, and which stretched from the Loire to the frontiers of Murcia, and from the western coast of the Bay of Biscay, with few interruptions, almost to the Black Sea. In the thirteenth century the Catalan dialect more resembled that of the Gascon Béarnais, or the Western Languedocian, than of the neighbouring Provence, but centuries of intercourse have since modified it, and the three dialects of Catalonia, Valencia, and the Balearic Isles must now be classed as a Provençal speech.

The tongues of all these successive occupiers of the soil have doubtless left traces in the noble Spanish language, but in very unequal proportions. A very few words belong to the old Iberian speech, but it is to that, perhaps, that Spanish owes the purity and the paucity of its vowel sounds, as from the Arabic it has gained the gutturals which have prevented its sinking to the effeminate softness of the Italian, and it still preserves the lofty sonority of the Latin. Some few of the elements of its vocabulary may be traced to the Keltic, less to the Teutonic languages. From Arabic it has taken more, and those words of more important character. But the bulk of the language still remains Latin. It is essentially one of the Romance dialects which sprang from the "lingua rustica," the country speech of the decaying Roman Empire. It has been calculated that six-tenths of its words are Latin, a tenth Gothic or Teutonic, one-tenth liturgical and Greek, one-tenth American or modern borrowings, and one-tenth Arabic. But as to this last, we must not forget that the different parts of the vocabulary of a language have a very different value. Some could be well dispensed with, some are of first necessity. There are words which we only see in print, and seldom or never hear spoken; there are words which belong only to science or to pedantry; but there are others which are in daily and hourly use, and whose employment is many times more frequent than the whole number of words in all the rest of the language put together. It is thus that the contribution of Arabic to Spanish vocabulary is of far more importance than is apparent by its numerical proportion; many of the most common terms, especially of those used in the south of Spain, are of Arabic origin.

Thus has been formed the noble Spanish tongue, the richest and most dignified of all that have sprung from the decay of Latin. Marvellously adapted to oratory and to verse, most incisive and mordant in the tongues of the lowest class, stately and sonorous almost to a fault, it is yet unequalled in grace and tenderness in the old romances and in the mouths of women and of children. Italian is its only rival. While reading its stately sentences, and marking the majestic rhythm of Scio's grand translation of the Bible and of its other religious literature, we can well understand why Spain's greatest emperor, the lord of many lands and of many tongues, spoke Spanish only to his God. It is rare to find a foreigner who has mastered Spanish, who does not ever afterwards delight in its use above all other tongues except his own.

The population of Spain, according to the census of 1877, is 16,625,000, including the Balearic and Canary Islands, and the North African possessions. The number of inhabitants in Spain has fluctuated much at different periods, according as war, emigration, or bad government have affected the condition of the people. In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries the population, according to the only estimates procurable, was about 9,000,000; in 1621, at the close of Philip III.'s reign, it had sunk to 6,000,000, the lowest point on record; it gradually rose from 7,500,000 at the end of the seventeenth century to 10,500,000 at the close of the eighteenth. The wars of Napoleon then lowered it by 500,000, but in 1821 it had recovered, and reached 11,600,000. A more rapid increase then took place till 1832, when the population numbered 14,600,000. The Carlist and civil wars which marked the beginning of the reign of Isabella II. reduced it by more than 2,000,000, if the returns are exact. In 1837 and in 1846 it stood at 12,200,000. In 1857 at 15,500,000, whence it mounted rapidly to 16,800,000 in 1870, a total which the late Carlist war and that in Cuba has reduced by some 200,000; and at the last census, 1877, as said above, the returns were 16,625,000.

The number of inhabitants to the square mile is 90, just half that of France, about a third that of Great Britain, and a fifth that of Belgium. This comparative scarcity is easily accounted for when we consider that nearly one-half (46 per cent.) of the territory still remains uncultivated; and although a considerable portion of this consists of mountain or of naturally sterile soil, a still larger portion of it is susceptible of some kind of cultivation, and even the portion under cultivation would under good husbandry, support a much larger population than it actually does.

More than two-thirds (66.75 per cent.) of the whole working population of Spain are engaged in agriculture, and the total produce, including cereals and cattle of all kinds, wine and fruits, cork, woods, esparto grass, &c., after supplying the demand for home consumption, leaves a surplus of agricultural produce for exportation of the value of 14,000,000l. sterling. Those engaged in manufacturing industry and in commerce are reckoned at 10½ per cent, of the working population; but in Spain, as elsewhere, the relative numbers are slowly changing, following the conditions of modern European life; a greater proportionate number are annually withdrawn from agriculture, and are being added to the population of the great towns, and to the manufacturing industries. Thus, until the last census the highest population of Spain per square kilometre was to be found, not in the manufacturing provinces of Barcelona and Valencia, nor in the great mining provinces, but in the fishing and agricultural province of Pontevedra, in Galicia. In 1870 Pontevedra numbered 107, Barcelona 98 inhabitants to the square kilometre. In 1877 it is Barcelona that numbers 108, and Pontevedra 100 only. Next after these provinces come the two Basque ones of Guipuzcoa 88, and Biscay 87. The one almost wholly agricultural, the other mining and agricultural. The nearest after them is the province of Madrid, with only 77 per square kilometre, and Corunna and Alicante with 75. These figures will, we think, sufficiently indicate the character of Spanish industry.