полная версия

полная версияEnglish: Composition and Literature

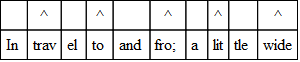

Variations in Metres. In music the bar or measure is not always filled with exactly the same kind of notes arranged in the same order. If the signature reads 3/8, the measure may be filled by any notes that added together equal three eighth notes. It may be a quarter and an eighth, an eighth and a quarter, a dotted quarter, or three eighth notes. So, in poetry the verses are not always as regular as in “Marmion” and “Hiawatha,” although poetry is more regular than music and there are usually few variations of metre in any one poem. A knowledge of the most common forms of variation is necessary to correct scansion.

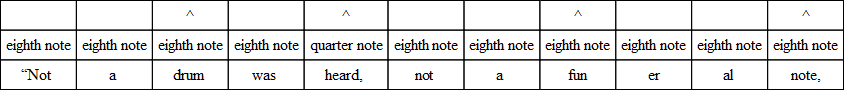

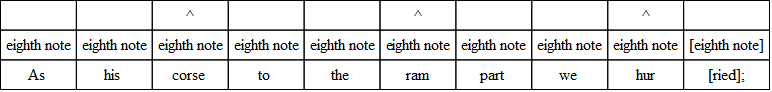

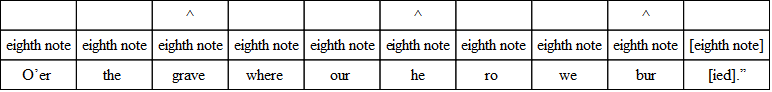

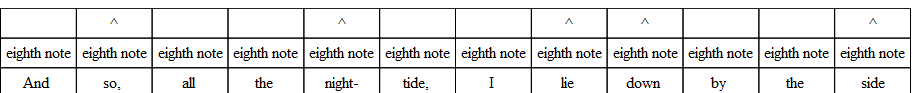

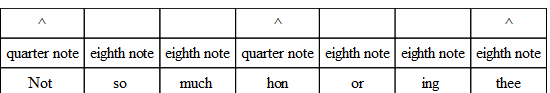

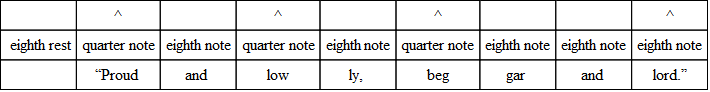

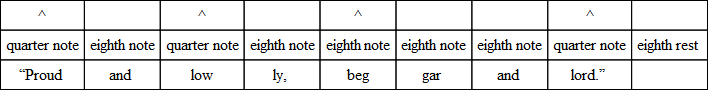

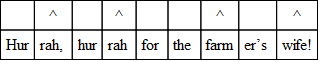

The commonest variation in verse is the substitution of three eighths for the quarter and the eighth, or the eighth and the quarter. And the very opposite of this often occurs; that is, the substitution of the two-syllable foot for the three-syllable foot. The following, from “The Burial of Sir John Moore,” illustrates what is done. Notice, however, that the beat is quite regular, and the lines lilt along as if there were no change.

In reading this the first time, a person is not likely to notice that there are three feet in it containing but two syllables. The rhythm is perfectly smooth, and cannot be called irregular. The accent remains on the last syllable of the foot.

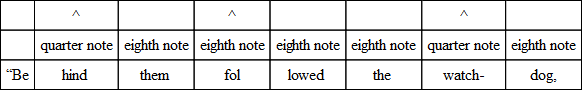

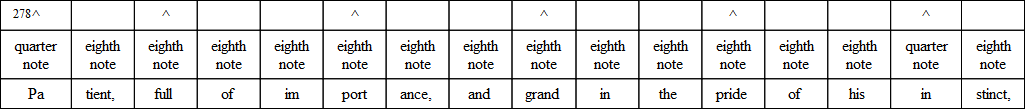

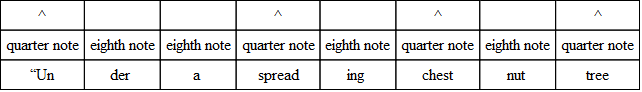

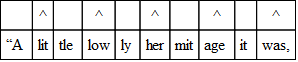

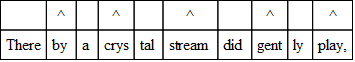

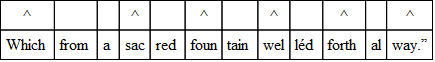

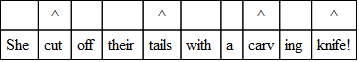

In the following selection from “Evangeline,” trochees are substituted for dactyls, yet there is no break in the rhythm. It does not seem in the least irregular.

These examples are enough to illustrate the fact that one kind of foot may be substituted for another and not make the rhythm feel irregular. So long as the accent is not changed from the first syllable to the last, or from the last to the first, there is no jar in the flow of the lines. The trochee and the dactyl are interchangeable; and the iambus and the anapest are interchangeable.

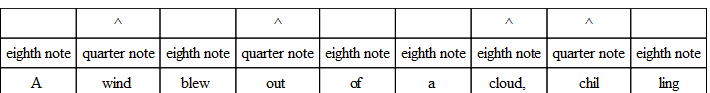

We may take a step further. There are many times when some sudden change of thought, some strong emotion forces a poet to break the smooth rhythm, that the verses may harmonize with his feeling. Such a variation is like an exclamation or a dash thrown into prose. The following is taken from “Annabel Lee.” The regular foot has the accent on the last syllable. It is anapestic, in tetrameters and trimeters. But note the shudder in the third line when the accent is changed on the word “chilling.” The music and the thought are in perfect harmony.

“And this was the reason that, long ago,In this kingdom by the sea,

Another beautiful example is found in the last stanza of the same poem. It is in the first two feet of the fifth line. Here the regular accent has yielded to an accent on the middle syllable and there are two amphibrachs. Notice, too, how it is almost impossible to tell in the next foot whether the accent goes upon the second or upon the third syllable. It is hovering between the form of the first two feet and the anapest of the last foot.

“For the moon never beams, without bringing me dreamsOf the beautiful Annabel Lee;And the stars never rise, but I feel the bright eyesOf the beautiful Annabel Lee;

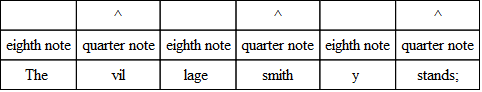

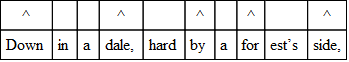

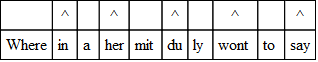

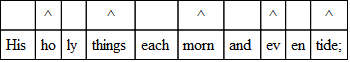

As has already been said, the iambus is the common foot of English verse. It is made of a short and a long syllable. At the beginning of a poem an unaccented syllable seems weak; and so very frequently the first foot of a poem is trochaic; often the first two or three feet are of this kind. At such a place the irregularity does not strike one. The following is an illustration:—

In this stanza the prevailing foot is iambic, but the first foot is trochaic. In the following beautiful lines by Ben Jonson, there is the same thing:—

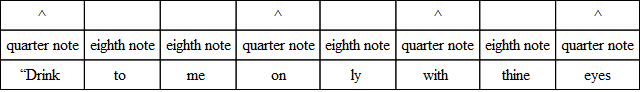

A similar substitution may occur in any other verse of the stanza; but we feel the change more than when it is found in the first verse. The second stanza of Jonson’s song furnishes an example of the substitution of a trochee for an iambus:—

“I sent thee late a rosy wreath,

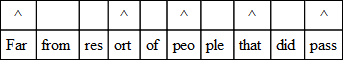

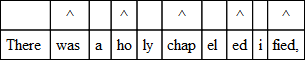

Of all the great poets, but few have been such masters of the art of making musical verse as Spenser. The following stanza is from “The Faerie Queene;” and the delicate changes from one foot to another are so skillfully made that one has to look twice before he finds them.

First and Last Foot. From the lines on “The Burial of Sir John Moore,” another fact about metres may be derived. The second and fourth lines apparently have one too many syllables. This may occur when the accent is upon the last syllable of the foot; that is, when the foot is an iambus or an anapest.

Again, the last foot of each line may be one syllable short. This may occur when the accent is on the first syllable of a foot; that is, when the foot is trochaic or dactylic. The scheme is like this:

The last foot of a verse of poetry, then, may have more or fewer syllables than the regular number; still the foot takes up the regular time and cannot be deemed unrhythmical.

The first foot of a line, too, may contain an extra syllable; a good example has been given in the lines on page 273, beginning,—

“Ah, the autumn days fade out, and the nights grow chill.”

And the first foot of a line may lack a syllable, as in the first line of “Break, Break, Break,” by Tennyson.

In a line like the following, it is sometimes difficult to tell whether the syllable is omitted from the first or the last foot. If from the first, the verse is iambic, and is scanned like this:—

If the last foot is not full, the line is trochaic.

Now if the whole of “London Bridge,” from which this line is quoted, be read, there will be found several lines that are trochaic beyond question; and the last line of the chorus is iambic. The majority of trochaic lines leads us to decide that the verse is trochaic. From this example one learns to appreciate how nearly alike are trochaic and iambic verses. Both are composed of alternating accented and unaccented syllables; and the kind of metre depends upon which comes first in the foot. In Blake’s “Tiger, Tiger,” there is not a line that clearly shows what kind of verse the poet used. If the unaccented syllable is supplied at the beginning the poem is iambic; if at the end, it is trochaic.

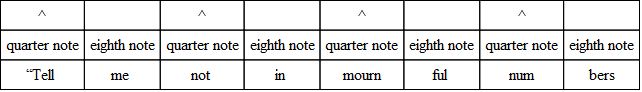

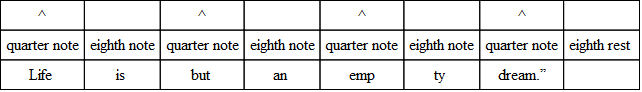

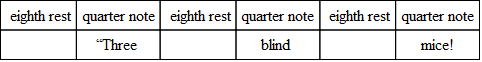

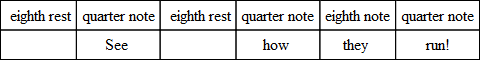

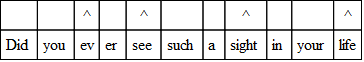

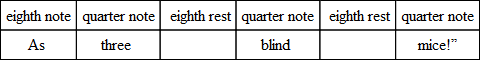

“Tiger, Tiger, burning brightIn the forests of the night,What immortal hand or eyeFramed thy fearful symmetry?”Silences may occur in the middle of a verse of poetry as well as at the beginning or the end. In the following nursery rhyme it is clear that the prevailing foot is anapestic, though several feet are iambic, and in the first two lines and the last line a single syllable makes a foot. Silences are introduced here as rests are in music.

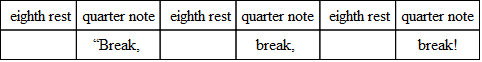

Like this is the scansion of Tennyson’s “Break, Break, Break.”

In scanning, then, it is necessary—

First. To determine by reading a number of verses the kind of foot that predominates, and to make this the basis of the metrical scheme.

Second. To remember that one kind of foot may be substituted for another, at the will of the poet, introducing into the poem a delicate variety of rhythm.

Third. To keep in mind that the first foot of a verse and the last foot may have more or fewer syllables than the regular foot of the poem.

Fourth. That silences, like rests in music, may be introduced into a verse and give to it a perfect smoothness of rhythm.

Kinds of Poetry. It is a difficult thing to give a definition of poetry. Many have done so, yet no one has been fortunate enough to have his definition go without criticism. In general, it may be said that poetry deals with serious subjects, that it appeals to the feelings rather than to the reason, that it employs beautiful language, and that it is written in some metrical form.

Poetry has been divided into three great classes: narrative, lyric, and dramatic.

Narrative poetry deals with events, real or imaginary. It includes, among other varieties, the epic, the metrical romance, the tale, and the ballad.

The epic is a narrative poem of elevated character telling generally of the exploits of heroes. The “Iliad” of the Greeks, the “Æneid” of the Romans, the “Nibelungen Lied” of the Germans, “Beowulf” of the Anglo-Saxons, and “Paradise Lost” are good examples of the epic.

The metrical romance is any fictitious narrative of heroic, marvelous, or supernatural incidents derived from history or legend, and told at considerable length. “The Idylls of the King” are romances.

The tale is but little different from the romance. It leaves the field of legend and occupies the place in poetry that a story or a novel does in prose. “Marmion” and “Enoch Arden” are tales.

A ballad is a short narrative poem, generally rehearsing but one incident. It is usually vigorous in style, and gives but little thought to elegance. “Sir Patrick Spens,” “The Battle of Otterburne,” and “Chevy Chase” are examples.

Lyric poetry finds its source in the author’s feelings and emotions. In this it differs from narrative poems, which find their material in external events and circumstances. Epic poetry is written in a grand style, generally in pentameter, or hexameter; while the lyric adopts any verse that suits the emotion. The principal classes of lyric poetry are the song, the ode, the elegy, and the sonnet.

The song is a short poem intended to be sung. It has great variety of metres and is generally divided into stanzas. “Sweet and Low,” “Ye Banks and Braes o’ Bonnie Doon,” “John Anderson, My Jo, John,” are songs.

An ode is a lyric expressing exalted emotion; it usually has a complex and irregular metrical form. Collins’s “The Passions,” Wordsworth’s “Intimations of Immortality,” and Lowell’s “Commemoration Ode,” are well known.

An elegy is a serious poem pervaded by a feeling of melancholy. It is generally written to commemorate the death of some friend. Milton’s “Lycidas” and Gray’s “Elegy in a Country Churchyard” are examples of this form of lyric.

A sonnet is a lyric that deals with a single thought, idea, or sentiment in a fixed metrical form. The sonnet always contains fourteen lines. It has, too, a very definite rhyme scheme. Some of the best English sonnets have been written by Shakespeare, Wordsworth, and Mrs. Browning.

Dramatic poetry presents a course of human events, and is generally designed to be spoken on the stage. Because such poetry presents human character in action, the term “dramatic” has come to be applied to any poetry having this quality. Many of Browning’s poems are dramatic in this sense. In the first sense of the word, dramatic poetry includes tragedy and comedy.

Tragedy is a drama in which the diction is dignified, the movement impressive, and the ending unhappy.

Comedy is a drama of a light and amusing character, with a happy conclusion to its plot.

Exercises in Metres. Enough of each poem is given below so that the kind of metre can be determined. Always name the verse form and write the verse scheme. Some hard work will be necessary to work out the irregular lines, but it is only by work on these that any ability in scanning can be gained. Always read a stanza two or three times to get the swing of the rhythm. Remember the silences, and the substitutions that may be made.

1. “I stood on the bridge at midnightAs the clocks were striking the hour,And the moon rose over the city,Behind the dark church tower.“Among the long black raftersThe wavering shadows lay,And the current that came from the oceanSeemed to lift and bear them away.”2. “All things are new;—the buds, the leaves,That gild the elm-tree’s nodding crest,And even the nest beneath the eaves;—There are no birds in last year’s nest!”

3. “Meanwhile we did our nightly chores,—Brought in the wood from out of doors,Littered the stalls, and from the mowsRaked down the herd’s-grass for the cows;Heard the horse whinnying for his corn;And, sharply clashing horn on horn,Impatient down the stanchion rowsThe cattle shake their walnut bows;While, peering from his early perchUpon the scaffold’s pole of birch,The cock his crested helmet bentAnd down his querulous challenge sent.”

4. “You know, we French stormed Ratisbon:A mile or so away,On a little mound, NapoleonStood on our storming day;With neck out-thrust, you fancy how,Legs wide, arms locked behind,As if to balance the prone browOppressive with its mind.”

5. “Come, read to me some poem,Some simple and heartfelt lay,That shall soothe this restless feeling,And banish the thoughts of day.“Not from the grand old masters,Not from the bards sublime,Whose distant footsteps echoThrough the corridors of Time.“For, like strains of martial music,Their mighty thoughts suggestLife’s endless toil and endeavor;And to-night I long for rest.“Read from some humbler poetWhose songs gushed from his heart,As showers from the clouds of summer,Or tears from the eyelids start;“Who through long days of labor,And nights devoid of ease,Still heard in his soul the musicOf the wonderful melodies.”

6. “Hickory, dickery, dock,The mouse ran up the clock;The clock struck one,And the mouse ran down;Hickory, dickery, dock.”

7. “Two brothers had the maiden, and she thought,Within herself: ‘I would I were like them;For then I might go forth alone, to traceThe mighty rivers downward to the sea,And upward to the brooks that, through the year,Prattle to the cool valleys. I would knowWhat races drink their waters; how their chiefsBear rule, and how men worship there, and howThey build, and to what quaint device they frame,Where sea and river meet, their stately ships;What flowers are in their gardens, and what treesBear fruit within their orchards; in what garbTheir bowmen meet on holidays, and howTheir maidens bind the waist and braid the hair.’”

(In this quotation we have blank verse; that is, verse that does not rhyme. It is iambic pentameter,—the most common verse in great English poetry. What poems are you familiar with that use this verse-form?)

1. “A wet sheet and a flowing sea,A wind that follows fastAnd fills the rustling sailsAnd bends the gallant mast;And bends the gallant mast, my boys,While like the eagle freeAway the good ship flies, and leavesOld England on the lee.“O for a soft and gentle wind;I heard a fair one cry;But give to me the snoring breezeAnd white waves heaving high;And white waves heaving high, my lads,The good ship tight and free—The world of waters is our home,And merry men are we.“There’s tempest in yon horned moon,And lightning in yon cloud;But hark the music, mariners!The wind is piping loud;The wind is piping loud, my boys,The lightning flashes free—While the hollow oak our palace is,Our heritage the sea.”2. “Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary,Over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore,While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping,As of some one gently rapping, rapping at my chamber door—‘’T is some visitor,’ I muttered, ‘tapping at my chamber door—Only this, and nothing more.’”

3. “Somewhat back from the village streetStands the old-fashioned country-seat,Across its antique porticoTall poplar trees their shadows throw;And from its station in the hallAn ancient timepiece says to all,—‘Forever—never!Never—forever!’”

4. “Listen, my children, and you shall hearOf the midnight ride of Paul Revere,On the eighteenth of April, in seventy-five;Hardly a man is now aliveWho remembers that famous day and year.”

5. “Sweet and low, sweet and low,Wind of the western sea,Low, low, breathe and blow,Wind of the western sea!Over the rolling waters go,Come from the dying moon, and blow,Blow him again to me;While my little one, while my pretty one, sleeps.“Sleep and rest, sleep and rest,Father will come to thee soon;Rest, rest, on mother’s breast,Father will come to thee soon;Father will come to his babe in the nest—Silver sails all out of the westUnder the silver moon:Sleep, my little one, sleep, my pretty one, sleep.”

6. “See what a lovely shell,Small and pure as a pearl,Lying close to my foot,Frail, but a work divine,Made so fairily wellWith delicate spire and whorl,How exquisitely minute,A miracle of design!”

(If the pupils have Palgrave’s “Golden Treasury of Songs and Lyrics,” they have a great fund of excellent material illustrating all varieties of metrical variation. There are very few pieces of literature that illustrate so many varieties of metre as Wordsworth’s “Ode on the Intimations of Immortality.”)

APPENDIX

A. SUGGESTIONS TO TEACHERS

The Course of Study on pages xx-xxvi contemplates five days a week for the study of English. The text which is to be the subject of the term’s work should first be studied for a few weeks. After it has been mastered, three days of each week should be given to literature and two to composition. In practice I have found it best to have the study of literature occupy three consecutive days,—for example, Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday. This arrangement leaves Monday and Friday for composition. Friday is used for the study of the text-book and for general criticism and suggestion. On Monday the compositions should be written in the classroom. To have them so written is, at least during the first year, distinctly better. The first draft of the composition should be brought to class ready for amendment and copying. During the writing the teacher should be among the pupils offering assistance, and insisting upon good penmanship. Care at the beginning will form a habit of neatness, and keep the penmanship up to a high standard.

The arrangement suggested is only one plan. This works well. Many others may be adopted. But no plan should be accepted which makes the number of essays fewer than one a week; nor should the number of days given to literature be smaller than three a week.

During the second year, if the instructor thinks it can be done without loss, the compositions may be written outside of school hours and brought to class on a definite day. A pupil should not be allowed to put off the writing of a composition any more than a lesson in geometry. On Monday of each week a composition should be handed in; irregularity only makes the work displeasing and leads to shirking. Writing out of school gives more time for criticism and study of composition, and during the second year this extra time is much needed.

By the third year the pupils certainly can do the work out of school. As the compositions increase in length, more time will be necessary for their preparation. The teacher should, however, know exactly what progress has been made each week; and by individual criticisms and by wise suggestions she should help the pupil to meet the difficulties of his special case.

In order that the instructor may have time for individual criticism, she should have two periods each day vacant in which to meet pupils for consultation. To make this clear, suppose that a teacher of English has one hundred pupils in her classes. She should have no more, for one hundred essays a week are enough for any person to correct. If there be six recitation periods daily, place twenty-five pupils in each of four sections for the study of literature, composition, and general criticism. This leaves two periods each day to meet individuals, giving ten pupils for each period. These should come on scheduled days, with the same regularity as for class recitation. The pupil’s work should have been handed in on the second day before he comes up for consultation, in order that the teacher may be competent to give criticisms of any value. The inspiration of the first reading cannot be depended upon to suggest any help, nor is there time for such a reading during the recitation.

There will be need of class recitation in argument. Ten days or two weeks are all that is necessary for text-book work. This should be done before pupils read the “Conciliation.” In the reading constantly keep before the pupils the methods of the author.