полная версия

полная версияEnglish: Composition and Literature

Only a little removed from metaphor is epithet. An epithet is a word, generally a descriptive adjective or a noun, used, not to give information, but to impart strength or ornament to diction. It is like a shortened metaphor. It is very often found in impassioned prose or verse. Notice that in each epithet there is a comparison; that the figure is based on likeness.

“Here are sever’d lipsParted with sugar breath.”“Base dog! why shouldst thou stand here?”

Personification is a figure that ascribes to inanimate things, abstract ideas, and the lower animals the attributes of human beings. It is plain that there must be some resemblance of the lower to the higher, else this figure could not be used. Personification, like the epithet, is a modification of the metaphor. Indeed, in every personification there is also a metaphor.

“When the sweet wind did gently kiss the treesAnd they did make no noise.”“But ever heaves and moans the restless Deep.”

Apostrophe is an address to the dead as if living; to abstract ideas or inanimate objects as if they were persons. It is a variety of personification.

“O Caledonia! stern and wild,Meet nurse for a poetic child!”“Wee, modest, crimson-tippèd flower,Thou’s met me in an evil hour;For I maun crush amang the stoureThy slender stem.”“Milton! thou shouldst be living at this hour.”Allegory is a narrative in which material things and circumstances are used to illustrate and enforce high spiritual truths. It is a continued personification. Bunyan’s “Pilgrim’s Progress” and Spenser’s “Faerie Queene” are good examples of allegory.

All these figures are varieties of metaphor. In them there is always an implied, not an expressed, comparison.

A simile is an expressed comparison between unlike things that have some common quality. This comparison is usually indicated by like or as.

“Ilbrahim was like a domesticated sunbeam, brightening moody countenances, and chasing away the gloom from the dark corners of the cottage.”

(Does this figure change to another in its course?)

“How far that little candle throws its beams!So shines a good deed in a naughty world.”Of retired Dutch valleys, Irving wrote:—

“They are like those little nooks of still water which border a rapid stream; where we may see the straw and bubble riding quietly at anchor, or slowly revolving in their mimic harbor, undisturbed by the rush of the passing current.”

Figures based upon Sentence Structure. There are a number of figures that express emotion by simply changing the normal order of the sentence. Among these are inversion, exclamation, interrogation, climax, and irony.

Inversion is a figure intended to give emphasis to the thought by a change from the natural order of the words in a sentence.

“Thine be the glory!”

“Few were the words they said.”

“He saved others; himself he cannot save.”

Exclamation is an expression of strong emotion in abrupt, inverted, or elliptical phrases. It is among sentences what the interjection is among words.

“How far that little candle throws its beams!”

“Oh, what a rogue and peasant slave am I!”

Interrogation is a figure in which a question is asked, not to get an answer, but for the sake of emphasis.

“Do men gather grapes from thorns, or figs from thistles?”

“Fear ye foes who kill for hire?Will ye to your homes retire?”“Am I a coward?”

Climax is a figure in which the intensity of the thought and emotion gradually increases with the successive groups of words or phrases. (See p. 211.)

“Your children do not grow faster from infancy to manhood than they [the American colonists] spread from families to communities, from villages to nations.”

Irony is a figure in which one thing is said and the opposite is meant.

“And Job answered and said, No doubt but ye are the people, and wisdom shall die with you.”

“O Jew, an upright judge, a learned judge!”

Four other figures should be mentioned: metonymy, synecdoche, allusion, and hyperbole.

Metonymy calls one thing by the name of another which is closely related to the first. The most common relations are cause and effect, container and thing contained, and sign and the thing signified.

“From the cradle to the grave is but a day.”

“I did dream of money-bags to-night.”

Synecdoche is that figure of speech in which a part is put for the whole, or the whole for a part.

“Fifty sail came into harbor.”

“The redcoats are marching.”

Allusion is a reference to something in history or literature with which every one is supposed to be acquainted.

“A Daniel come to judgment! yea, a Daniel!”

Men still sigh for the flesh pots of Egypt; still worship the golden calf.

There is no “Open Sesame” to the treasures of learning; they must be acquired by hard study.

Milton and Shakespeare are full of allusions to the classic literature of Greece and Rome.

Hyperbole is an exaggerated statement made for effect.

“He was tall, but exceedingly lank, with narrow shoulders, long arms and legs, hands that dangled a mile out of his sleeves, feet that might have served for shovels, and his whole frame most loosely hung together.”

“And, if thou prate of mountains, let them throwMillions of acres on us, till our ground,Singeing his pate against the burning zone,Make Ossa like a wart!”Exercises in Figures. Name the following figures. Of those that are based upon likeness, tell in what the similarity consists. In many of the selections more than one figure will be found.57

1. “The long, hard winter of his youth had ended; the spring-time of his manhood was turning green like the woods.”

2. A pig came up to a horse and said, “Your feet are crooked, and your hair is worth nothing.”

3. “The words of his mouth were smoother than butter, but war was in his heart; his words were softer than oil, but they were drawn swords.”

4. “The lily maid of Astolat.”

5. “O Truth! O Freedom! how are ye still bornIn the rude stable, in the manger nursed!”6. “The birch, most shy and ladylike of trees,Her poverty, as best she may, retrieves,And hints at her foregone gentilitiesWith some saved relics of her wealth of leaves.”

7. “O friend, never strike sail to a fear! Come into port grandly, or sail with God the seas!”

8. “Primroses smile and daisies cannot frown.”

9. “How deeply and warmly and spotlessly Earth’s nakedness is clothed!—the ‘wool’ of the Psalmist nearly two feet deep. And as far as warmth and protection are concerned, there is a good deal of the virtue of wool in such a snow-fall. It is a veritable fleece, beneath which the shivering earth (‘the frozen hills ached with pain,’ says one of our young poets) is restored to warmth.”

10. “We can win no laurels in a war for independence. Earlier and worthier hands have gathered them all. Nor are there places for us by the side of Solon and Alfred and other founders of States. Our fathers have filled them.”

11. “I put on righteousness, and it clothed me; my judgment was as a robe and diadem.

“I was eyes to the blind, and feet was I to the lame.

“I was father to the poor; and the cause which I knew not I searched out.

“And I brake the jaws of the wicked, and plucked the spoil out of his teeth.”

12. “His head and his heart were so well combined that he could not avoid becoming a power in his community.”

Spenser, writing of honor, says:—

1. “In woods, in waves, in wars, she wonts to dwell,And will be found with peril and with pain;Nor can the man that moulds an idle cellUnto her happy mansion attain:Before her gate high God did Sweat ordain,And wakeful watches ever to abide;But easy is the way and passage plainTo pleasure’s palace: it may soon be spied,And day and night her doors to all stand open wide.”2. “Over the vast green sea of the wilderness, the moon swung her silvery lamp.”

3. “The peace of the golden sunshine was supreme. Even a tiny cloudlet anchored in the limitless sky would not sail to-day.”

4. “A short way further along, I come across a boy gathering palm. He is a town boy, and has come all the way from Whitechapel thus early. He has already gathered a great bundle—worth five shillings to him, he says. This same palm will to-morrow be distributed over London, and those who buy sprigs of it by the Bank will know nothing of the blue-eyed boy who gathered it, and the murmuring river by which it grew. And the lad, once more lost in some squalid court, will be a sort of Sir John Mandeville to his companions—a Sir John Mandeville of the fields, with their water-rats, their birds’ eggs, and many other wonders. And one can imagine him saying, ‘And the sparrows there fly right up into the sun, and sing like angels.’ But he won’t get his comrades to believe that.“

5. “We wandered to the Pine ForestThat skirts the Ocean’s foam;The lightest wind was in its nest,The tempest in its home.The whispering waves were half asleep,The clouds were gone to play,And on the bosom of the deepThe smile of heaven lay;It seemed as if the hour were oneSent from beyond the skiesWhich scattered from above the sunThe light of Paradise.“We paused amid the pines that stoodThe giants of the waste,Tortured by storms to shapes as rudeAs serpents interlaced,—And soothed by every azure breathThat under heaven is blown,To harmonies and hues beneath,As tender as its own:Now all the tree-tops lay asleepLike green waves on the sea,As still as in the silent deepThe ocean woods may be.”6. “When a bee brings pollen into the hive, he advances to the cell in which it is to be deposited and kicks it off as one might his overalls or rubber boots, making one foot help the other; then he walks off without ever looking behind him; another bee, one of the indoor hands, comes along and rams it down with his head and packs it in the cell as the dairy-maid packs butter into a firkin.”

7. “For thy desires

Are wolfish, bloody, starved, and ravenous.”

8. “What a piece of work is man! how noble in reason! how infinite in faculty! in form and moving how express and admirable! in action how like an angel! in apprehension how like a god! the beauty of the world! the paragon of animals!”

9. “And in her cheeks the vermeil red did shew

Like roses in a bed of lilies shed.”

10. He betrayed his friend with a Judas kiss.

11. “A true poet is not one whom they can hire by money and flattery to be a minister of their pleasures, their writer of occasional verses, their purveyor of table wit; he cannot be their menial, he cannot even be their partisan. At the peril of both parties let no such union be attempted. Will a Courser of the Sun work softly in the harness of a Dray-horse? His hoofs are of fire, and his path is through the heavens, bringing light to all lands; will he lumber on mud highways, dragging ale for earthly appetites from door to door?”

12. “Hath a dog money? is it possibleA cur can lend three thousand ducats?”13. “Kind hearts are more than coronets,And simple faith than Norman blood.”

14. They sleep together,—the gray and the blue.

15. “Have not the Indians been kindly and justly treated? Have not the temporal things—the vain baubles and filthy lucre of this world—which were apt to engage their worldly and selfish thoughts, been benevolently taken from them? And have they not, instead thereof, been taught to set their affections on things above?” (Quoted from Meiklejohn’s “The Art of Writing English.”)

16. “Poetry is truth in its Sunday clothes.”

17. “His words were shed softer than leaves from the pine,

And they fell on Sir Launfal as snows on the brine,

That mingle their softness and quiet in one

With the shaggy unrest they float down upon.”

18. Too much red tape caused a great amount of suffering in the beginning of the war.

19. “Roll on, thou deep and dark blue ocean, roll!

Ten thousand fleets sweep over thee in vain.”

20. “The old Mountain has thrown a stone at us for fear we should forget him. He sometimes nods his head, and threatens to come down.”

21. “But pleasures are like poppies spread:You seize the flow’r, its bloom is shed;Or like the snow falls in the river,A moment white—then melts for ever;Or like the borealis race,That flit ere you can point their place;Or like the rainbow’s lovely formEvanishing amid the storm.”CHAPTER XI

VERSE FORMS 58

No pupil has passed through the graded schools without being told that he should not sing verses, though no one is inclined to sing prose. One can scarcely help singing verse, and one cannot well sing prose.

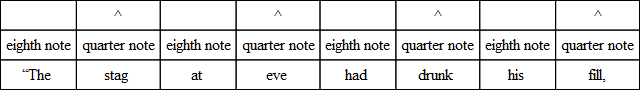

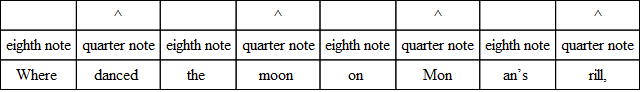

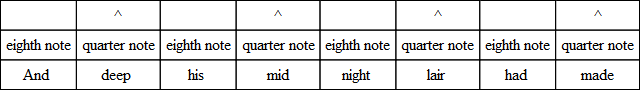

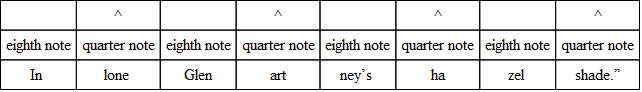

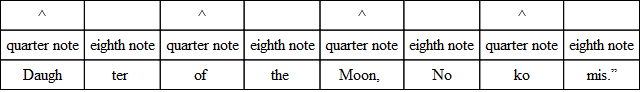

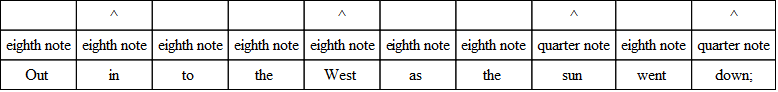

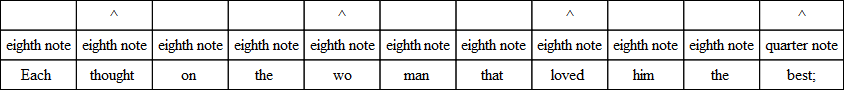

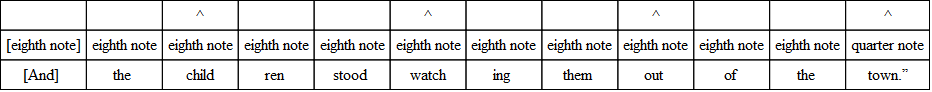

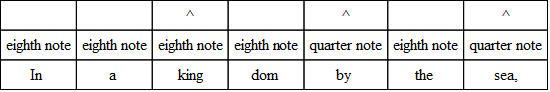

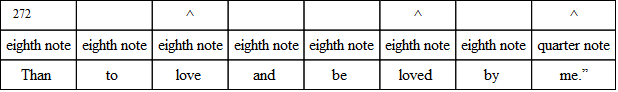

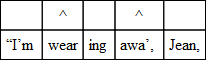

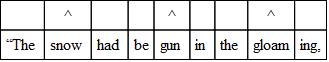

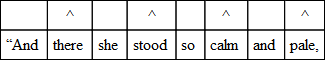

What is there about the form that leads a person to sing verses of poetry? For example, when a person reads the first lines of “The Lady of the Lake,” he falls naturally into a sing-song which can be represented by musical notation as follows:—

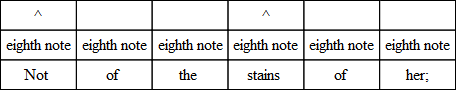

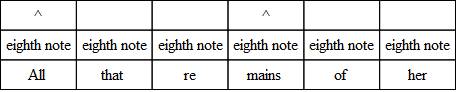

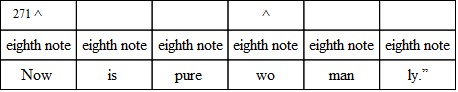

The second, fourth, sixth, and eighth syllables in each of these lines are naturally accented in reading, while the other syllables are read without stress. The eight syllables of each line fall naturally into groups of two, an unaccented syllable followed by an accented syllable, just as in the musical notation given, an unaccented eighth note is followed by an accented quarter.

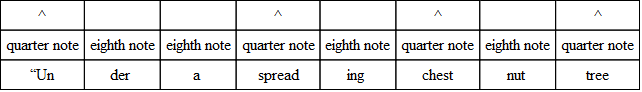

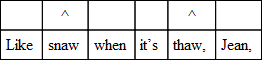

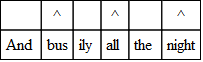

In “Hiawatha” the accented syllable comes first, and the unaccented follows it.

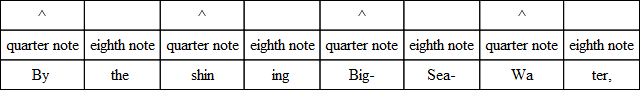

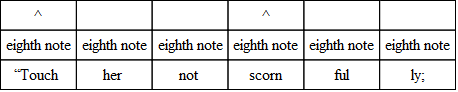

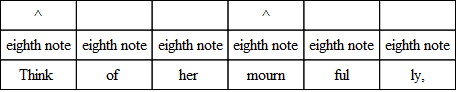

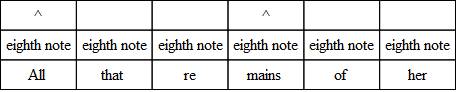

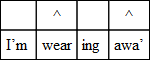

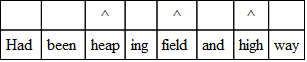

So, too, there are groups in which there are three syllables. The accent may fall on any one of the three. In the following stanza from “The Bridge of Sighs,” the accent falls on the first syllable of each group.

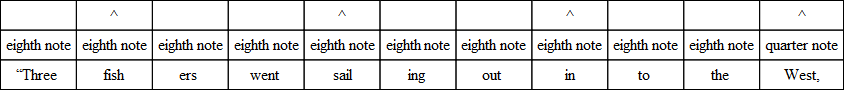

The accent may be upon the second syllable of the group. This is not common. The following is from “The Three Fishers.”

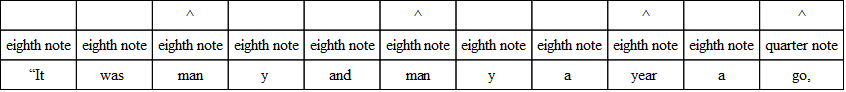

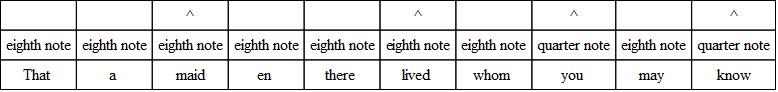

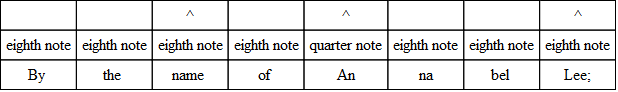

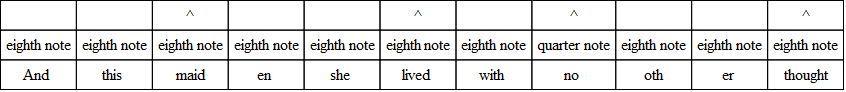

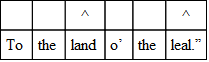

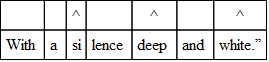

Or the accent may be upon the last syllable of the group. This form is very common. It is found in the poem entitled “Annabel Lee.”

Poetic Feet. If all these verses be observed carefully, it will be seen that in each group of syllables there is one accented syllable combined with one or two unaccented. Such a group of syllables is called a foot. The foot is the basis of the verse; and from the prevailing kind of foot that is found in any verse, the verse derives its name.

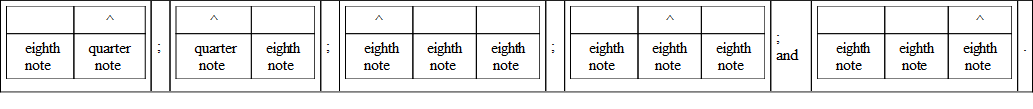

A foot is a group of syllables composed of one accented syllable combined with one or more unaccented. It will be noticed further that if musical notation be used, all of these forms are but variations of the one form, represented by the standard measure 3/8. They are:—

Accordingly there are five forms of poetic feet made of this musical rhythm. Of these, four are in common use.

An Iambus is a two-syllable foot accented on the last syllable. Verse made of this kind of feet is called iambic. It is the most common form found in English poetry. Example:—

“The stag at eve had drunk his fill.”

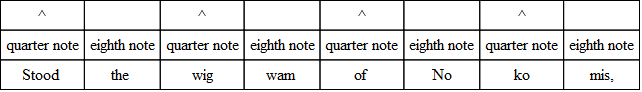

A Trochee is a two-syllable foot accented on the first syllable. Verse made of this kind of feet is called trochaic. Example:—

“Stood the wigwam of Nokomis.”

A Dactyl is a three-syllable foot accented on the first syllable. Such verse is called dactylic. Example:—

“Touch her not scornfully.”

An Amphibrach is a three-syllable foot accented on the middle syllable. It is uncommon. Example:—

“Three fishers went sailing out into the West.”

An Anapest is a three-syllable foot accented on the last syllable. Example:—

“It was many and many a year ago.”

A Spondee is a very uncommon foot in English. It consists of two long syllables accented about equally. It occurs as an occasional foot in a four-syllable rhythm. No English poem is entirely spondaic. The four-syllable foot and the spondee are so uncommon that there is little use in the pupil’s knowing more than that there are such things. The example below is quoted from Lanier’s “The Science of English Verse.”

Kinds of Metre. A verse is a single line of poetry. It may contain from one foot to eight feet.

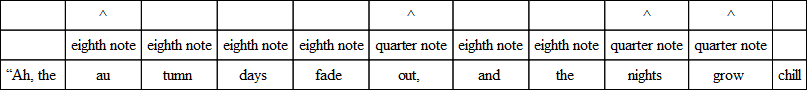

A line made of one foot is called monometer. It is never used throughout a poem, except as a joke, but it sometimes occurs as an occasional verse in a poem that is made of longer lines. The two lines which follow are from the song of “Winter” in Shakespeare’s “Love’s Labour’s Lost.” The last is monometer.

“Then nightly sings the staring owlTu-whit.”A line containing two feet is called dimeter. It also is uncommon; but it does sometimes make up a whole poem; as, “The Bridge of Sighs,” already mentioned. Another example is:—

It is frequently met as an occasional line in a poem. Wordsworth’s “Daisy” shows it.

“Bright Flower! for by that name at last,When all my reveries are past,I call thee, and to that cleave fast,Sweet, silent creature!That breath’st with me in sun and air,Do thou, as thou art wont, repairMy heart with gladness, and a shareOf thy meek nature!”A line containing three feet is called trimeter. Example:—

A line containing four feet is called tetrameter. “Marmion” is written in tetrameters. See the extract on p. 276.

A line containing five feet is called pentameter. This line is very common in English poetry. It gives room enough for the poet to say something, and is not so long that it breaks down with its own weight. Shakespeare’s Plays, Milton’s “Paradise Lost,” Tennyson’s “Idylls of the King,”—indeed, most of the great, serious work of the master-poets has been done in this verse.

A line containing six feet is called hexameter. This is the form adopted in the Iliad and the Odyssey of the Greeks, and the Æneid of the Romans; it has been used sometimes by English writers in treating dignified subjects. “The Courtship of Miles Standish” and “Evangeline” are written in hexameter.

Verses of seven and eight feet are rare; they are called heptameter and octameter, respectively. The heptameter is usually divided into a tetrameter and a trimeter; the octameter, into two tetrameters. Poe’s “Raven” and Tennyson’s “Locksley Hall” are in octameters, and Bryant’s “The Death of the Flowers” is in heptameters.

A verse is named from its prevailing kind of foot and the number of feet. For example, “The Merchant of Venice” is in iambic pentameter, and “The Courtship of Miles Standish” is in dactylic hexameter.

Stanzas. A stanza is a group of verses, but these verses are not necessarily of the same length. Monometer, dimeter, and trimeter are not often used for a whole stanza; but they are frequently found in a stanza, introducing variety into it. A stanza made up of tetrameter alternating with trimeter is very common. The stanzas from “Annabel Lee” and “The Village Blacksmith,” found on pages 278 and 279, are excellent examples.

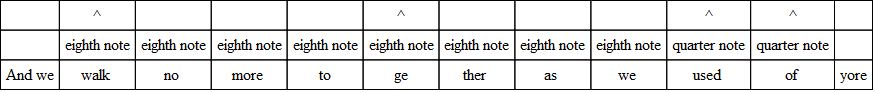

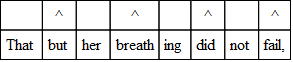

Scansion. Scansion is the separation of a verse of poetry into its component feet. Poetry was originally sung or chanted by bards and troubadours. The accompaniment was a simple strumming on a harp of very few strings, and was hardly more than the beating of time. The chanting must have been much like the sing-song that some people fall into when reading verses now. The first thing in scanning a line of poetry is to drop into its rhythm,—to let it sing itself. When the regular accent is felt, the lines can easily be separated into their metrical feet. Read these lines from “Marmion,” and mark only the accented syllables.

The marked verses have an accented syllable preceded by an unaccented syllable. Such a foot is iambic. There are four feet in each verse; so the poem is written in iambic tetrameter. In the same way, one decides that “The Song of Hiawatha” is written in trochaic tetrameter.