полная версия

полная версияA Short History of H.M.S. Victory

By 4.30 p.m. the action was over, and a victory was reported to Lord Nelson just before his death. We left him in the cockpit, where he was attended by Dr. Scott, the chaplain, and Mr. Burke, the purser. He had sent the doctor away to attend to the other wounded, and lay in great agony, fanned with paper by those two officers, and giving his last directions as to those he loved; but ever and anon interrupted by the cheers of the “Victory’s” crew, he would ask the cause, and being told it was a fresh enemy’s ship that had struck her flag, his eye would flash as he expressed his satisfaction. He frequently asked for Captain Hardy, and that officer not being able to leave the deck, his anxiety for his safety became excessive, and he repeated, “he must be killed;” “he is surely destroyed.” An hour had elapsed before Hardy was able to come to him, when they shook hands, and the Admiral asked—“How goes the day with us.” “Very well, my Lord,” was the reply; “we have about 12 of the enemy in our possession.”

After a few minutes of conversation, Hardy had again to return on deck, and shortly after the “Victory’s” port guns redoubled their fire on some fresh ships coming down on her, and the concussion so affected Lord Nelson that he cried in agony, “Oh! ‘Victory!’ ‘Victory!’ how you distract my poor brain;” but, weak and in pain as he was, he indignantly rebuked a man, who in passing through the crowded cockpit struck against and hurt one of the wounded.

Captain Hardy again visited him in about another hour, and, holding his Lordship’s hand, congratulated him on a brilliant victory, saying, he was certain that 14 ships had surrendered. “That is well,” he answered, “but I bargained for 20.” Then, Hardy having again to go on deck, Nelson after emphatically telling him to anchor, and declaring his intention to direct the fleet as long as life remained, said, “kiss me Hardy,” the Captain knelt down and kissed him, when he said, “Now I am satisfied. Thank God I have done my duty.” Twenty minutes later he quietly passed away, having again and again repeated to his last breath, the words above mentioned. They were, it has been well remarked, the whole history of his life.

On the firing ceasing, the “Victory” had lost 57 killed and 103 wounded, and found herself all but a wreck. The tremendous fire to which she was exposed, when leading her line into action, had caused great damage, at a very early period of the battle, and before she herself fired a gun, many of her spars were shot away, and great injury was done to the hull, especially the fore part of it.

At the conclusion of the action, she had lost her mizen-mast, the fore-topmast had to be struck to save the foremast; the mainmast was not much better, and it took all the exertions of her crew to refit the rigging sufficiently to stand the bad weather that followed.

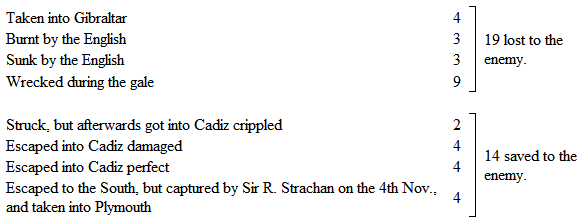

The actual number of prizes taken by 5 p.m., on October 21st, were 19; so that Nelson’s desired number was nearly made up; but from their disabled condition, they were nearly all wrested from us by the gales that succeeded the battle. Lord Nelson had doubtless foreseen this, and thence his wish to anchor, and as a matter of fact, most of those few ships and prizes that did anchor, rode the gale out in safety and were saved; but the majority of the vessels were either anchorless, or in such deep water that they could not with convenience anchor.

The “Victory’s” trophy, the Redoutable, was one of those that sunk after the action in deep water, and in her, as in many of the other vessels lost, went down her prize crew of British seamen. The English fleet were in nearly as disabled a state as their prizes, as might be expected after such a battle, and it is a matter of wonder that some of them were not lost on the treacherous shoal that swallowed up so many of the captured ships.

The enemy’s fleet of 33 sail was disposed of as follows:

On the 22nd, the day after the battle, the breeze was fresh from the S.S.W., and it was all the ships could do to increase their distance from the shore, such as were manageable towing those that were totally dismasted. On the 23rd it blew a gale, and then the misfortunes of the victors commenced; the hawsers of many of the ships towing parted, and the English vessels had too much to do to save themselves and one another, to attempt to get hold of the prizes again, so they drifted helplessly away, two to be blown safe into Cadiz, but seven to meet an awful end amongst the breakers of that shallow coast. Five others were burnt and sunk to ensure their not falling into the enemy’s hands again.

On the morning of this day, the remnant of the enemy’s ships put to sea to attempt to recapture some of their friends, but the gale coming on, the only result was the loss of two more of themselves, one of which fell into our hands before going ashore. The “Victory,” with the small amount of sail she could show to the gale, laboured deeply in the heavy sea, and on the 24th, when the wind moderated a little, she was taken in tow by the Polyphemus. In the afternoon, managing to rig up some jury topmasts and a mizen-mast, she was more comfortable, but at 5 p.m. next day, on the storm increasing, the towing hawser parted, the mainyard carried away, and her sails split to ribbons. With nothing now to steady her, the “Victory” rolled dangerously and unmanageably, and an anxious night was passed, but happily for her as well as other of our ships, the violence of the wind abated in the morning, and the Neptune taking her in tow, after two days brought her safely into Gibraltar.

In the meantime Lord Nelson’s remains had been placed in a cask of brandy, as the best means at hand of preserving them, and on the 3rd of November, having refitted, the “Victory,” accompanied by the Belleisle, sailed on the melancholy duty of conveying the body of her hero to England, and, after a most boisterous passage, reached Spithead, on December 4th.

Here she was the object of a most intense and reverential attention, her battered sides, with, in many places, the shot yet sticking in them; her still bloody decks; her jury masts and knotted rigging;—all attested the severity of the ordeal she had gone through; while the flag that still waved, but at half-mast, reminded the spectator that the great Admiral who had such a short time before sailed from that very anchorage to victory, had now, also, returned to his grave. Amongst other injuries, the “Victory’s” figure-head, a coat of arms supported by a sailor on one side and a marine on the other, was struck by shot, which carried away the legs of the soldier and the arm of the sailor, and the story goes (but we cannot vouch for its truth), that all the men who lost legs in the action were marines, and those who lost arms sailors. The figure-head is still the same, but the wounded supporters have been replaced by two little boys, who, leaning affectionately on the shield, seem certainly more fitted for the peaceful life of Portsmouth Harbour than for the hard times their more warlike predecessors lived in.

The “Victory” left Spithead on December 11th for Sheerness, which was reached on the 22nd, when the hero’s remains, having been deposited in the coffin made from the mainmast of the L’Orient (the French flagship at the Nile), were transferred to Commissioner Grey’s yacht for conveyance to Greenwich, and thence to St. Paul’s. As this was done, Lord Nelson’s flag, which had flown half-mast ever since the action, was lowered for the last time. The “Victory” then went to Chatham, paid off on the 16th of January, 1806, and underwent another thorough repair.

It was agreed on all sides that the enemy fought harder and more desperately at Trafalgar than they had ever done before, and at the same time it was undeniable that the victory was the most complete ever gained. The exultation that arose in the breasts of all who heard how the pride of the enemy had been humbled, was embittered by the thought that their hero and idol was dead; that he, whose very name ensured victory, would never again lead his ships to the thickest of the fight, and men doubted whether even the triumph of Trafalgar was not too dearly bought. But Nelson had done his work. Never after did the enemy show a large fleet at sea; and he himself fell, as he had often wished, in the moment of victory; leaving behind him an undying fame, and such an example of entire devotion to his country’s service as had never before been equalled in the world’s history.

Mr. Devis, the painter of the picture of the “Death of Nelson,” now on board the “Victory,” went round in her from Spithead to Sheerness. On the voyage he took portraits of all the characters depicted, and sketched the locality, so that this picture may be considered as a truly historical and faithful one.

In the commencement of 1808, our ally, Sweden, being threatened by an invasion by Russia, a fleet was sent to the Baltic to assist them, of which Sir James Saumarez was appointed Commander-in-Chief, and the “Victory” was once more called into active service as his flagship. She was commissioned on 18th March, by Captain Dumaresq, and sailed for the Baltic shortly after, arriving at Gottenburg at the end of April. To this place the fleet was followed by a force of 10,000 men under Sir John Moore, who, however, in consequence of disagreements, were withdrawn in June and returned to England, leaving Sir James with the “Victory” and ten 74-gun ships, to protect Sweden against Russians, Danes, French, and Prussians. In August, the advanced division of the Anglo-Swedish fleet met the Russians, and chasing them into Rogerwick, destroyed one 74 and blockaded the remainder in that port. Sir James, who was on his way north, received this intelligence a few days afterwards, and hastened to join.

On arriving on August 30th, off Rogerwick, he found the enemy safe inside, and at once made preparations for an attack. On the 1st September, in company with the Goliath, the “Victory” stood in to reconnoitre, and having silenced a battery that engaged them, a good view of the enemy’s position was obtained, and the next day fixed for the assault. Unfortunately, the next day broke with a gale of wind, the ships were unable to move, and the storm lasting eight days, gave the enemy time to bring troops from Revel, and to erect batteries on all sides, making any attempt at attack hopeless. Sir James therefore, after watching the port till September 30th, sailed for Carlscrona, where he remained till winter warned him to depart for England. He arrived in the Downs on 9th December, and at once struck his flag.

The operations in the Baltic in this, and the other four years in which the “Victory” was flagship of Sir James Saumarez, were, as far as she herself was concerned, mainly confined to political schemes and transactions; the active work, such as it was, being done by the frigates and gun-boats, many of which latter, however, were manned by the “Victory’s” officers and men; the Russian fleet never came out again, but remained shut up in Cronstadt, which was much too strong to be attacked; thus the proceedings are of very little interest, and beyond the fact of her being employed, we have little to record.

She went out almost immediately after the striking of Saumarez’s flag in 1808, as a private ship in the squadron which was dispatched to Corunna to bring home the army of the unfortunate Sir John Moore, and returned to Portsmouth on January 23rd. During this cruise she was commanded by Captain Searle, but on her going round to Chatham for a refit, Captain Dumaresq again returned to her, and Sir James Saumarez re-hoisting his flag on April 8th, 1809, she once more sailed for the Baltic, on the navigation being reported open. The best part of this year was spent by the “Victory” and fleet of 10 sail, in blockading the Russian ships in Cronstadt. One successful boat attack was made, when 8 of the enemy’s gun-boats were destroyed, but otherwise there was no fighting. In the autumn, Sweden was forced to make peace with Russia, on terms dictated by the latter, that would have doubtless been harder, had not the presence of the British fleet prevented any active employment of the Russian ships. The “Victory” returned to the Downs by Christmas, and the Admiral struck his flag.

On the 11th March, 1810, Saumarez resumed his command, and proceeded to Hawke Roads, in Sweden, and thence to Hano Bay, near Carlscrona, where he laid most of the year, having a ship or two watching the Russians; but as they never ventured out, nothing was done, and “Victory” sailed on 10th October, with 1000 sail of merchantmen under her convoy. These were seen safely through the Belt, and Sir James then remained with all his ships at Hawke Bay, as late as the ice permitted him, to prevent the possibility of the Russian fleet from the White Sea entering the Baltic. The Swedes about this time were compelled by Napoleon to declare war with England, but the feelings between the two countries were privately as friendly as before. Hearing that the Archangel ships were laid up, Saumarez sailed for England, and arriving on 3rd December, hauled down his flag.

The “Victory” then again made a trip to the coast of Portugal, this time with the flag of Rear-Admiral Sir Joseph S. Yorke, who took a squadron of 7 line-of-battle ships to Lisbon, with a reinforcement of 6500 men for Sir Arthur Wellesley, then blockaded in his intrenchments at Torres Vedras by Massena; but she returned to the Nore in time to hoist Sir James Saumarez’s flag for the fourth year, on the 2nd April, 1811.

He proceeded to Wingo Sound, and there remained nearly the whole year. The anomalous state of affairs between Sweden and ourselves continued, and as public enemies and private friends we remained until the end of the year, when Sweden concluded an alliance with England. The “Victory’s” boats made various expeditions against the Danes, and captured several gun-boats.

On December 18th, the fleet left Wingo for England; and on the 23rd a gale arose, by which they were dispersed, and H.M.S. St. George and Defence were wrecked on the western coast of Jutland, and the Hero off the Texel; but the “Victory” and other ships weathered it in safety, and anchored at St. Helen’s on Christmas Day, when Sir James struck his flag.

On April 14th, 1812, it was again hoisted, and on the 28th, “Victory” sailed with a squadron of 10 sail of the line, and took her station as usual at Wingo. The naval operations this year were more active than before; the Danes had equipped a good many frigates and small craft for attacks on the Swedish coast, and frequent engagements took place between them and our smaller vessels; but “Victory” was not herself in action. In October, orders were received from England to send his flagship home, and on the 15th of that month, Sir James shifted his flag to the Pyramus, and “Victory” sailed for England, and arriving at Portsmouth, was paid off in November.

This was the last active service of this glorious old ship, though she was on the point of being sent to sea again in 1815, when no less than six Admirals, on applying for commands, named the “Victory” as the ship they would wish to have, although there were many new ships, larger, and carrying much heavier ordnance; but the prestige attached to the “Victory,” besides her well known sailing qualities, outweighed every other consideration. Waterloo, however, soon put an end to that war, and the “Victory” was never re-commissioned.

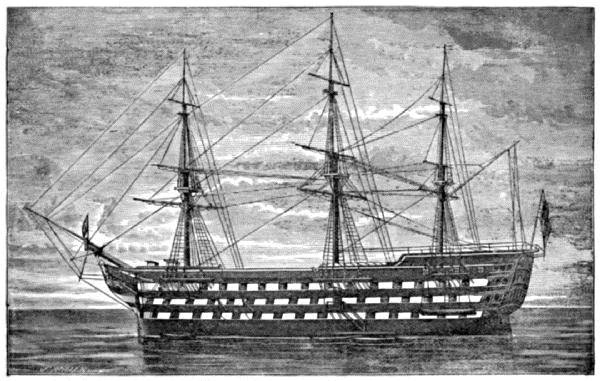

THE “VICTORY” AS SHE NOW LIES IN PORTSMOUTH HARBOUR.

In 1825 she was made flagship in Portsmouth harbour, and ever since that date, with but few intervals, she has continued to bear the flags of Admirals, who, having like her, spent their lives in the service of their country, terminate their active careers by holding the highest post in the British Navy,—the command at Portsmouth. Every year, as the 21st October, the anniversary of Trafalgar, comes round, daylight discovers the “Victory” with a wreath of laurel at each mast-head, a continual memorial of the deeds of that ever-to-be-remembered day, when at one blow the naval power of two great nations was crippled, and the superiority of England established without dispute.

In 1844, Queen Victoria happened to be passing through the harbour on this day, and learning the cause of the decoration of the “Victory,” at once pulled on board, and went round the ship. Her Majesty evinced much emotion, when shown the almost sacred spots where the hero fell and died; and plucking some leaves from the wreath that enshrined the words on the poop, “England expects that every man will do his duty,” kept them as a memento.

The “Victory” now no longer bears the Admiral’s flag; the increasing numbers of seamen in our depôts, rendered in 1869 a larger ship more convenient, and she is retained in her position in the harbour solely as a reminiscence of the past; and it almost seems a pity that she cannot be now fitted up internally, as nearly as possible as she was at Trafalgar, that the thousands of annual visitors might form a better idea of the state of the decks of a man-of-war of the olden time when going into action; and that in these days of rapid and enormous changes in both shipbuilding and ordnance, a type of the man-of-war that won England her pre-eminence, might be preserved to all time.

1

Not including one that only fires aft.

2

“A private ship” is a man-of-war that does not have an Admiral on board.