полная версия

полная версияA Short History of H.M.S. Victory

Jervis blockaded Cadiz during the summer, the “Victory” serving in sometimes the outer, sometimes the in-shore squadron, and sending her boats to take part in the night attacks, undertaken by Commodore Nelson, with the hopes of shaming the Spaniards to come out. On one of these occasions, 5th July, some of her men were wounded. But the Dons were not to be lured out, and on the approach of winter, Earl St. Vincent withdrew his vessels to the Tagus, and amongst other ships sent the “Victory” home, with the prizes taken on February 14th. She arrived at Spithead on October 1st, and thence going to Chatham, paid off on November 26th, after another long and eventful commission of nearly five years duration.

Worn out, and unfit for further active service, the poor old “Victory” was here degraded to the office of prison hospital ship, which she filled for two years, when, unwilling that such a favourite and fast sailing ship should be lost to the country, the Admiralty directed her to be thoroughly repaired. This took a year, and in the spring of 1801 she came out of dock almost a new ship, but she was not ready for service in the Baltic campaign of that date, and had rest at Chatham for still two years.

The peace concluded between England and France in 1802 was not of long duration, for on April 29th, 1803, war was again declared; this had been foreseen, and early in the month, great preparations were made in all the dockyards. Lord Nelson was appointed Commander-in-Chief in the Mediterranean, and selected the “Victory” as his flagship. She was commissioned at Chatham, on April 9th, and on 16th May arrived at Spithead. Nelson was waiting for her, but could not get away for a few days; and such was his impatience to sail, that in answer to everyone who spoke to him on the 19th of his departure, he said, “I cannot sail till to-morrow, and that’s an age.”

He went on board on the 20th, and sailed in a violent squall of wind and rain the same afternoon, having orders to speak Admiral Cornwallis off Brest, and if necessary to leave the “Victory” with him, and go on a frigate. On the 22nd he was in sight of Brest, but no Cornwallis was to be seen, and after chafing for a day, his anxiety did not permit him to wait any longer, so striking his flag in the “Victory,” he went on board the Amphion, leaving the former ship to find the Admiral of the Channel Fleet, and if not required, to follow him with all speed.

Within forty hours after Lord Nelson left him, Captain Sutton met Lord Cornwallis, and was immediately permitted to resume his voyage. A few days after, the “Victory” fell in with the Ambuscade, a French frigate, formerly an English one, which she re-captured, and on the 12th June, she anchored at Gibraltar. After watering, she left on the 15th, called at Malta on the 9th July, and on the 30th, joined the squadron of 5 line-of-battle ships, off Cape Sicie, when Lord Nelson at once shifted into her, bringing Captain T. Masterman Hardy with him, from the Amphion, Captain Sutton of the “Victory” exchanging.

For 18 months subsequent to this, there is no fact worth recording in the history of the “Victory.” During that time Lord Nelson, with a fleet that averaged 10 sail of the line, closely watched the road of Toulon, where a French fleet lay at anchor, going occasionally to Agincourt Sound, in Sardinia, for water, &c., but the French never showed any sign of moving, until the beginning of 1805, though every stratagem was tried to entice them to come out.

Spain had declared war with England on 12th December, 1804, and Buonaparte had formed a great plan for the invasion of Britain, the first step to the accomplishment of which, was to gain the command of the Channel. This could only be done by placing an overwhelming force of ships there, and by misleading the English as to his design. With this object in view, Admiral Villeneuve, who was now in command at Toulon, prepared for sea, and embarked on board his 11 ships, 3,500 soldiers.

His orders, as subsequently ascertained were, to proceed to the West Indies, effect a junction there with a fleet of 21 sail from Brest, land his troops, and if opportunity offered, ravage our colonies; then return with speed to Ferrol, where the Spaniards were to have a fleet of at least 25 sail ready to join him, and with this overpowering force, he was expected to keep our ships at bay, while the bold originator of this scheme, Napoleon, crossed the Channel himself, at the head of 170,000 men. We shall see how much easier this was to plan than to carry out.

On January 12th, 1805, well nigh worn out with watching, hoping, and fearing, his ships and their rigging rotten, Nelson left his station off Toulon, for the anchorage at Agincourt Sound, which he called his “home,” to water and refit, leaving his two frigates to watch the enemy.

The fleet now consisted of the following ships:—“Victory,” 104, Royal Sovereign, 100, Canopus, 80, Spencer, 74, Leviathan, 74, Tigre, 80, Superb, 74, Belleisle, 74, Swiftsure, 74, Conqueror, 74, Donegal, 74.

On the 17th Villeneuve put to sea, and on the 19th January, at 2 p.m., the fleet in Agincourt Sound was electrified by the appearance of the frigates, with the welcome signal flying, “enemy is at sea.” In two hours the ships were under weigh, and made sail for the passage between Biche and Sardinia, a passage so narrow that the ships had to proceed in single line, directed by the lights of their next ahead, and led by the “Victory,” who took them through in safety.

Nelson had nothing to guide him as to where the French were bound, but he knew they could not be far off, and dispatched the few frigates he had to scour the coasts in search, but all to no purpose—no tidings could be obtained. A gale that arose on the 21st, and that lasted a week, blew in the teeth of the fleet as it attempted to go south, and Nelson was wild at the thought that they had escaped him. The only place his reasoning led him to suppose they could have sailed for, was Egypt, and thither he turned his ships’ heads. He arrived off Alexandria on 7th February, but found no sign of them there either; immediately he retraced his steps, and called off Malta, and here he learnt that the French fleet were dispersed and disabled by the gale on the 21st, and had returned to Toulon, scattered and crippled.

Nelson, in a letter to Admiral Collingwood, thus writes on the subject. “Buonaparte has often made his brags that our fleet would be worn out by keeping the sea; that his was kept in order and increasing by being kept in port; but he now finds I fancy, if Emperors hear truth, that his fleet suffers more in one night, than ours in a year.”

By March 12th, the British fleet, after struggling with a continuation of gales, succeeded in regaining their station off Toulon, and to their joy, saw the enemy still at anchor, and after watching them till the 27th, they proceeded to Palma Bay to get that refit they so much required, as during all this cruise, every ship had been strained to her utmost.

Villeneuve took the first opportunity to escape again, after his ships were repaired, and on 29th March ran out of Toulon roads; on the 31st he was discovered off Cape Sicie, by the Phœbe, which vessel lost no time in communicating her intelligence to the Admiral, who was again on his way to Toulon; and once more the exciting chase began. The frigates, most unfortunately, lost the French ships, and could give no intelligence of their apparent destination. Again Nelson thought of Egypt, and proceeded off Sicily, sending ships right and left to get information, and on the 15th April, when off Palermo, he first heard of the evident intention of the enemy to go westward. At once he made sail in pursuit, but the fates were against him, and while the French in their passage down the Spanish coast had been favoured with easterly winds, he could get nothing but westerly gales. “I believe,” he says, “this ill luck will go near to kill me.”

It was the 4th May, before the “Victory” and her consorts anchored in Tetuan Bay to water and provision. Sailing the next day, they put into Gibraltar for a few hours, and learnt nothing there, but that the enemy’s fleet had passed the Straits on the 8th April, nearly a month in advance of them. Nelson at once went to Cape St. Vincent, hoping to get news, and the next day he received the first reliable information from an American brig, which was to the effect, that on the 9th April, the French fleet of 11 sail had appeared off Cadiz, been joined by a squadron of five Spanish and 2 French line-of-battle ships, and immediately resumed their voyage. He then heard from an Admiral Campbell in the Portuguese service, that their destination was the West Indies; this tallied with his own ideas, and he instantly decided on following.

On May 10th he put into Lagos Bay to get more provisions, and on the 11th, having sent the Royal Sovereign back to the Mediterranean, as a slow sailer who was likely to hinder him, he started in pursuit of the 18 ships of the enemy, with but 10 of his own. His anxiety at this time was extreme; he was very ill, and had been told by his physicians that he ought to go home, but “salt beef and the French fleet is far preferable to roast beef and champagne without them;” he writes, “my health or my life even must not come into consideration at this important crisis.” Captain Hardy is reported to have said to him, “I suppose, my Lord, that by crowding all this sail you mean to attack those 18 ships?” “By God, Hardy,” said he, “that I do;” and on the passage over, he took every opportunity of making his plans known to his captains, that a success might be ensured if possible. Barbadoes was reached on June 4th, and here he received information that led him to suppose that either Tobago or Trinidad was the object of the combined fleet, who had been seen on the 28th May, and, embarking 2000 men, he hurried on for the latter island. Off Tobago he received corroborative news from an American schooner, who must have deceived him on purpose and all was preparation in the English fleet.

Early on the morning of the 7th June, the ships stood along the north shore of Trinidad; and had anything been wanting to confirm the intelligence they had received, it was supplied in the conflagration of a battery, that protected a little cove in the steep coast, and the flight of its garrison, who were seen speeding away in the direction of the town. The remembrance of Aboukir Bay rose in their minds, every man expected that the deeds of that glorious day would be repeated in the Gulf of Paria, and as the ships sailed, prepared for battle, through the Bocas of Trinidad, expectation was strained to the utmost, to catch the first glimpse of the enemy they fully relied on seeing on rounding the point.

What was their astonishment then on coming in view of the town, to find the Union Jack still waving over the forts, and no French men-of-war to be seen.

Nelson at once anchored for the night without communication, and early next morning sailed for Grenada.

In the meantime, the town of Puerto d’Espana, the capital of Trinidad, was the scene of the wildest excitement. The lieutenant of artillery in command of the above-mentioned out-post, finding a fleet close to him in the morning, and making no doubt it was that of the enemy (for no one knew of Nelson’s arrival in the West Indies), had burnt his barracks, thrown his guns over the cliff, and hastened back to the town, spreading dismay with the intelligence that the French were upon them. The inhabitants at once fled to the interior, the troops were drawn into the forts, and the town was left at the mercy of the French Republicans, of whom there were many in the island, and who now came forward and proclaimed themselves, believing their friends were at hand.

The movements of the fleet were inexplicable to the governor, and he was at once puzzled and relieved, when daylight revealed the strange ships underweigh, and leaving their shores. It was some days before the mystery was explained, and they learnt that Nelson had paid them a visit.

He, in the meanwhile, was hurrying along the chain of islands to the north, getting information, true or false, every day. On the 11th he heard that the enemy, now consisting of 20 sail, had passed Antigua, steering northward; and at once concluding that they were bound for Europe, he landed the troops at Antigua on the 12th, and left next day for Gibraltar, not without hopes of still catching them up.

This promptitude on the part of Nelson in following Villeneuve to the West Indies, doubtless saved some of our possessions there, as there was no force to withstand the combined fleets; but such was the terror of his name, that no sooner did the enemy hear of his approach, although he had but half their number of ships, than they immediately started again on their return, without attempting to carry out that part of their programme, which directed them to ravage our colonies.

Nelson’s squadron, after a most tedious voyage, arrived at Gibraltar on July 20th, when he went on shore; this was the first time for two years that he had put his foot out of the “Victory,” for such had been his anxiety during his long blockade of Toulon to be ready at any moment, that it had never suffered him to leave his ship for an instant. Nothing up to this time had been heard of the enemy, and the indefatigable Nelson, after watering and provisioning at Tetuan, sailed again on the 23rd July.

He spoke Admiral Collingwood’s squadron on 26th, and receiving information that the enemy had gone to the northward, he proceeded for Ushant, off which, on August 15th, he met Admiral Cornwallis with the Channel fleet of 24 sail of the line, and from him received an order to leave eight of the ships with him, and repair with “Victory” and Superb to Portsmouth.

The two ships arrived at Spithead on the 18th, when they were put in quarantine for a day, to Nelson’s great indignation; they were then released, and Nelson went to his home at Merton, to get that rest he so badly needed. The “Victory” remained at Spithead, and did what repairs she could at that anchorage during her brief stay.

A short account of the proceedings of the combined fleets up to this time, may tend to the elucidation of the state of affairs.

When Villeneuve made his escape from the Mediterranean, the Brest squadron attempted to put to sea to join him at Martinique, but the determined front put on by Lord Gardner, who commanded the Channel fleet, then blockading Brest, daunted the enemy, who put back again into port. This was failure number one, in Buonaparte’s scheme.

We have followed Villeneuve with his 20 sail of French and Spanish line-of-battle ships to Antigua; thence he proceeded for Brest, intending to effect a junction with the fleet awaiting him there; but on July 22nd, Sir Robert Calder, who was watching Ferrol and had been warned by a frigate from Lord Nelson of the probable approach of the enemy, met and engaged him, and though he numbered but 15 to 20, he took two ships of the line, and forced the French admiral from his design. This was the second breakdown in the programme; however, Villeneuve got into Ferrol and joined the ships there, which made his force 29 sail of the line, and with these he sailed on August 9th, but, for some unexplained cause, instead of now making his way to Brest, he turned south and entered Cadiz on the 21st, driving off Admiral Collingwood’s small squadron.

On September 2nd, Captain Blackwood, on his way to London with the news of the combined fleets having left Ferrol, called at 5 a.m. at Merton, where he found Lord Nelson up and dressed; the latter immediately said, “you bring me news of the French and Spanish fleets, I shall have to give them a drubbing yet;” and going up to town with him, offered his services to the Admiralty. These were gladly accepted, and the “Victory” again hoisted his flag on September 15th, and sailed the same day in company with the Euryalus, Captain Blackwood, which frigate he afterwards despatched ahead to direct that the “Victory” should not be saluted on her arrival, in order that the enemy should be unaware of the reinforcement. On the 28th of the same month he joined, and took command of, the fleet off Cadiz, which, by the junction of Sir Robert Calder’s ships to Admiral Collingwood’s now consisted of 29 sail.

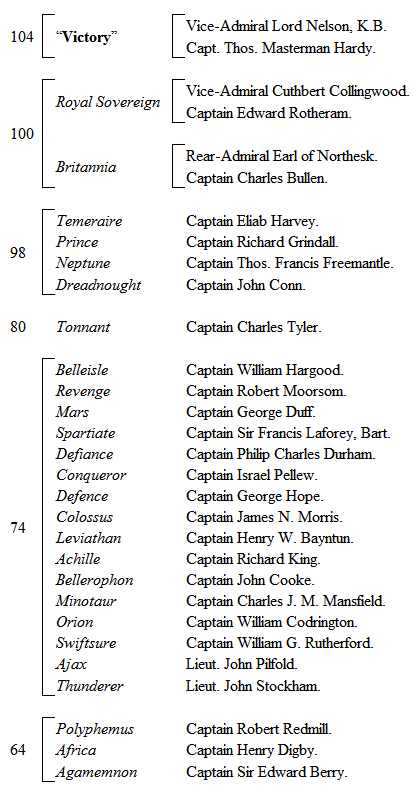

On October 4th, Nelson dispatched Rear-Admiral Louis with 5 sail of the line to Gibraltar, but a small squadron from England joined a few days afterwards, making up his fleet to the following 27 sail of the line.

Before continuing our narrative, we must again remind our readers that this is but the history of one ship, and that in our account of Trafalgar, only a sufficient general description of the movements of the fleet will be given, to render the “Victory’s” part intelligible; for details, we must again refer to James’s Naval History, where the most complete account of the action that has been published, will be found.

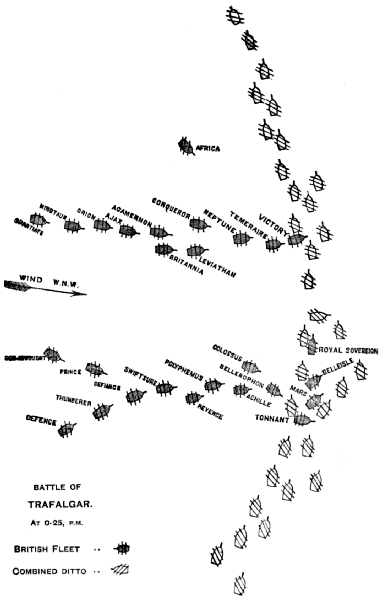

On 19th October, the Franco-Spanish fleet, of 33 sail of the line, under Admiral Villeneuve, as Commander-in-Chief, and Admiral Gravina, (Spanish), as second, came out of Cadiz, and, after some manœuvring, at daylight on the 21st, the two fleets were in sight of one another, being then about 20 miles west of Cape Trafalgar. The wind was light, from the W.N.W., and the enemy were in a straggling line on the starboard tack, under easy sail; the British fleet were in two columns on the port tack, and some ten miles dead to windward. At 6.50, the “Victory” made the signal to bear up, on which the enemy wore together, thus presenting his port broadside to the English fleet, which bore down with a very light wind right aft, and with all studding sails set; the “Victory” leading the port line, and the Royal Sovereign the starboard, the latter being somewhat in advance.

Thus the British very slowly closed with the enemy, Lord Nelson refusing to allow the Temeraire, his next astern, to take the lead, and thereby bear the brunt of the battle. His Lordship visited the decks of his ship, exhorted his men not to throw away a shot, and was received with cheers as he again went on deck. Having made every other signal to his fleet he thought necessary, he finished with that most celebrated one—“England expects that every man will do his duty,”—which, at 11.40, was hoisted at the “Victory’s” mizen-topgallant-masthead, and was received by most of the ships with cheers.

This made, Lord Nelson’s customary signal on going into action—“Engage the enemy more closely”—was hoisted at the main, and there remained until the mast was shot away.

At noon, the action commenced by the Fougoeux opening fire on the Royal Sovereign, on which the British Admirals hoisted their flags, and all their ships the white ensign, having also, each, two Union Jacks in the rigging. Twenty minutes later the enemy’s ships ahead of the “Victory” began a furious cannonade on her, which killed in a short time amongst many others, Mr. Scott, Lord Nelson’s secretary. Seeing Nelson’s intention to break the line, the enemy closed up ahead of him, making an almost impenetrable line; but the “Victory” still held her course, and steered straight for the mass of ships grouped round the Bucentaure, a French 80, on board of which was Villeneuve, the French Commander-in-Chief, though he never showed his flag during the action.

Nelson directed Captain Hardy to run on board any ship he chose, as it was evident they could not pass through the line without a collision, and at 12.30, not having as yet fired a single shot, the “Victory” passed slowly under the stern of the Bucentaure, so close as almost to be able to catch hold of her ensign, and discharge the port guns in succession right into her cabin windows, placing about 400 men hors de combat, by that one broadside, and almost disabling her from further resistance. The position of the ships at this moment is shown in the accompanying plan.

At the same time the “Victory” fired her starboard guns at two vessels on that side of her, and five minutes later ran on board the Redoutable, a French 74, hooking her boom iron into the Frenchman’s topsails, and so dropped alongside, the “Victory” being on the Redoutable’s port side, and the latter closing her lower deck ports to prevent boarding. A tremendous cannonade ensued, the “Victory” firing her port guns at the Bucentaure and Santissima Trinidada, her starboard ones being very fully employed by the Redoutable which was so close alongside, that the men on the “Victory’s” lower deck on each discharge dashed a bucket of water into the hole made in the enemy’s side by the shot, to prevent the spread of the fire that might have destroyed both ships indiscriminately.

During this time the British ships were coming into action one after another, but very slowly, as the wind, light all the morning, had now fallen to a mere air, barely sufficient to bring all our vessels up; thus the first ships engaged had dreadful odds against them, and the loss of life in them was great.

After bringing the Redoutable to close action as before described, Lord Nelson and Captain Hardy, side by side, calmly walked the centre of the quarter deck, from the poop to the hatchway. At about 1.25, in their walk forward his Lordship turned a little short of the hatchway, Captain Hardy took the other step, and turned also, and beheld the Admiral in the act of falling. He had been wounded by a musket ball fired from the mizen-top of the Redoutable, which struck him in the left shoulder as he turned, and thence descending, lodged in the spine. He sank on to the very spot that was still red with his secretary’s blood, and was raised by Sergeant Secker, of the Marines, and two seamen, who under Captain Hardy’s directions, bore him to the cockpit. “They have done for me at last, Hardy,” said the hero as he fell. “I hope not,” said Hardy. “Yes,” was the reply, “they have shot my backbone through.” But his presence of mind was still strong, and he gave directions for the tautening of the tiller ropes as he was carried below, and covered his face and decorations with a handkerchief, that he might not be recognised.

The cockpit was crowded with wounded, and with difficulty he was borne to a place on the port side, at the foremost end of it, and placed on a purser’s bed with his back resting against one of the wooden knees of the ship. Here the surgeon examined his wound, and at once pronounced it mortal.

In the meantime the battle raged furiously, the men stationed in the Redoutable’s tops (Nelson would allow none in the “Victory,” for fear of setting fire to the sails), had nearly cleared the “Victory’s” upper deck, 40 men being killed or wounded on the deck alone. The French, seeing this, attempted to board, but were driven back with great gallantry by the few men that remained, headed by Captain Adair, of the Marines.

At about 1.50 the Redoutable ceased firing, and two midshipmen and a few men were sent from the “Victory” to assist in putting out a fire that had burst out on board of her, and the “Victory” then proceeded to get herself clear, leaving her prize lashed to the Temeraire, that had just fouled her on the other side. The “Victory” was by this time so crippled in her spars and sails that all efforts on her part to get into close action (Lord Nelson’s favourite position), with another enemy were ineffectual; but she still continued engaged on the port side with the Santissima Trinidada and other ships; and later, with a fresh batch of the enemy’s ships that passed along the line and eventually escaped.