полная версия

полная версияThe Depot for Prisoners of War at Norman Cross, Huntingdonshire. 1796 to 1816

There are short notes on several others who were on parole at the Depot. General Brunet, captured at St. Domingo in 1803, his aide-de-camp, his adjutant, Col. Felix of the Artillery, and Lieut. Devoust of the Navy, son of the Senator of that name, are mentioned. There is a note that M. Bartin, a French naval officer, prisoner on parole about the space of eleven years, behaved himself extremely well all the time he lived with us. John Mien, servant to General Brunet, who was living in his eighty-fifth year in 1870, as a boy of seven witnessed the execution of Louis XVI., and heard the drums roll at Santerre’s command to drown the monarch’s speech.

Several of the parole prisoners married. M. Salvert, commander in the navy, married Helen Govstry of Leek Moor. Jean Toufflet, a sea-captain, left issue in the town; his widow, née Lorouds, died the 5th February 1870, æt. 84. M. Chouquet, a sea-captain, left a son living in 1870. Joseph Vattel, cook to General Brunet, married Sarah Spilsbury. One, Vandome, a naval officer and a most excellent linguist, used to render the English papers into his native tongue for the benefit of his comrades at the billiard-tables established by the officers.

That the prisoners on parole, like their fellow countrymen in close confinement, added to their means of living by their industry, is proved by the note in the history of Leek that there is in existence an old card, intimating that “James Francis Neau, of Derby Street, sold straw hats, beautiful straw, ivory and bone fancy articles, made by the French prisoners,” and many exquisite models of ships and other nick-nacks, still in existence, testify to the facile talent and marvellously patient industry of these prisoners.

This Francis Neau was a privateer officer who married a Mary Lees; she was living in 1870.

There was a remarkable duel. A Captain Decourbes had been fishing, and, coming in after curfew bell had tolled at 8 p.m., had to report himself to Captain Grey, R.N., the Commissary. He afterwards met a Captain Robert at the billiard-room at the Black’s Head, who grossly insulted him and struck him in the face, so that the duel became inevitable. Neau, who was present, was deputed to furnish them with firearms; but after ransacking the town, he could only succeed in borrowing one horse-pistol from a private in the Yeomanry. The two met on Balidone Moor at three the next morning, and tossed for the first shot. Decourbes won, and hit his adversary in the breast so that the ball entered at one side and came out at the other. Robert, who was previously lame and had come on to the ground on crutches, then, grievously wounded as he was, gathered himself up and returned the fire, shooting Decourbes in the nape of the neck. Lieut. Vird of the 72nd Regiment of Foot acted as Robert’s second; he was subsequently killed at Waterloo.

They all walked back together to Leek, the two combatants treating their wounds very lightly; but Decourbes’ wound went wrong, and he died of it in the course of ten days or a fortnight.

The number of prisoners at Leek never exceeded 200, and they came by detachments in 1803, 1805, 1809, and 1812, almost all clearing out after Napoleon’s abdication 5th April 1814.

It will not be forgotten that in the earlier period of the war the prisoners on parole in various parts of the country were all removed to Norman Cross; whether any similar change in their condition was experienced, after the resumption of hostilities in 1803, by the prisoners out upon their parole, remains a matter of uncertainty.

Passing now to the subject of the Exchange of prisoners, and the chances that a prisoner at Norman Cross or elsewhere had of obtaining his liberty by an exchange for an English prisoner of equal rank, it must be borne in mind that a large number of civilians were in captivity, especially in the second period of the war.

This practice of taking captive so many civilians in the second period of the war, 1803–15, was attributed to the British system of seizing all French vessels of every kind and making their crews captive. This practice was adopted as a retaliation for the first act of Buonaparte, then ruling France as First Consul, when hostilities were resumed in May 1803. As a reprisal for what he considered the dishonourable action of two British frigates in seizing in harbour French merchantmen before the formal declaration of war had reached France, the Consul ordered the immediate arrest of every British subject between the age of eighteen and sixty who happened to be in France at that time, thus throwing 10,000 peaceable travellers and others into captivity.

Wellington, replying 4th September 1813 to an application from Mr. J. S. Larpent requesting the General to obtain his release from captivity, wrote:

“In this war, which on account of the violence of animosity with which it is conducted, it is to be hoped will be the last, for some time at least, everybody taken is considered a prisoner of war, and none are released without exchange. There are several persons, now in my power, in the same situation as yourself in that respect, that is to say, non-combatants according to the known and anciently practised rules of war; among others there is the secretary of the Governor of San Sebastian. . . .” 107

Such being the spirit of the war, negotiations for exchange continually fell through.

In the early period it was the want of good faith on the part of the French, and the unfairness with which the exchange was conducted by them, that on more than one occasion put a stop to the general exchange which was going on. Thus in 1798, when a general exchange had been arranged, and the Depot at Norman Cross was rapidly emptying, the Samaritan cartel took 201 French prisoners to France, but returned with only 71 British. The Britannia carried over 150, and 450 were conveyed by two other cartels; the three returned without a single British prisoner. The captains of the vessels were told that there were no British prisoners to return, and they were ordered to sea at once, regardless of wind or weather.

During the early negotiations a return was furnished to show what had been the result of the general exchange up to the date when fresh arrangements were to be made, and it appeared that 6,056 British prisoners had been received from France, while she had received from the British 16,334, including 4,986 captured at Martinique and Guadeloupe. On 19th March 1798 by the fresh exchange France had received 12,543, Britain only 5,045, leaving a balance of 7,498 due to England. The earliest prisoners to be exchanged from Norman Cross left on 24th August 1797, only four months after the first prisoners had been received there. The contingent was sent to Lynn; it numbered 305, and consisted of 7 captains of privateers, 4 sergeants, 6 corporals, 148 soldiers, 127 seamen and 7 boys, and 6 not specified. They sailed in the Rosine, which had brought the same number of British to England.

The article of the agreement providing that the prisoners for exchange were not to be selected, but were to be taken according to the priority of their capture, was afterwards modified, so as to select the aged, the infirm, such as were not seamen, and boys under twelve years of age! Amid all the bickering and obstinacy on both sides in the negotiations as to the treatment and exchange of the prisoners, there is one instance which shows that the chivalrous spirit of the French was not dead.

In March 1797 M. Charretie, the French Commissary in England, enclosed a list of thirty-six British seamen to be released without exchange for their humanity in rescuing and aiding the crew of a French vessel bearing the appropriate name of Les Droits de l’Homme.

Although it was a traffic strictly forbidden, some of the prisoners sold their turn of exchange to their more wealthy comrades, the purchaser assuming the name of the vendor, and vice versa. If detected, the vendor forfeited his rights of exchange, and was kept a prisoner until the end of the war. Notwithstanding this regulation, it was said that one man had contrived to carry on these transactions from 1797 to 13th January 1800 without detection. This voluntary prolongation of the imprisonment surely helps to prove the falsity of the statements of the French as to the treatment of the prisoners by the British.

This practice of personating a fellow prisoner was carried out occasionally under more tragic conditions.

In the course of the investigations to establish the facts of the epidemic of 1800–01, a certificate was found with the name François le Fevre crossed out, and the name of Bernard Batrille substituted, with a note that the name of François le Fevre was assumed by Batrille when he entered the hospital to die of consumption. This was, doubtless, not the sole instance of such practices among the prisoners. A prisoner high up in the list for exchange, who knew that he was dying, would, when about to enter the hospital, for a sum of money or from friendship, exchange his current number and his name with another man low down in the list, the dying man, if this was done for payment, thus securing a sum of money for his heirs in France, and the other increasing his chance of release by exchange.

The case of Le Fevre and Batrille would have escaped detection, but for the special investigation made by Captain Woodriff to establish the identity of those who had died in the epidemic unrecognised. The investigation led to the identification among the living prisoners of François le Fevre, who had been personating Batrille, since he entered the hospital, and had died, and was buried in the name of the former man.

During the first period of the war, 1793–1802, exchange went on, with interruptions from the causes mentioned. The prisoners passed in a sluggish stream through Norman Cross, but so sluggish that many of them were there, confined or out on parole, during the whole five years. Notwithstanding the exchange the prisons were at times greatly overcrowded, and in 1801, when the French army in Egypt surrendered to Abercrombie, such was the burden of prisoners that no attempt was made to claim the troops as captives, but they were transported in British ships to France.

During the second period of the war negotiations for exchange completely failed. In April 1810, when there were about 10,000 British prisoners in France, and 50,000 French in Britain, Mr. Mackenzie was sent by the British Ministry to treat for a general exchange, the main condition in the British proposal being that for every French prisoner returned to France, a British prisoner of equal rank should be returned to Britain; that this should go on until the whole of the British prisoners were restored; and after that was accomplished, the British Government would continue the restoration of the French, on the understanding that France on her part returned to his native country, man for man, one of the prisoners of Britain’s allies—i.e. a Spanish or Portuguese of equal rank with the French prisoner handed over by Britain.

To this the French Emperor would not agree; he insisted that the British and their allies should be reckoned as one army, and that for four Frenchmen released from the British prisons and returned to France, only one British subject should be returned to England, and three other prisoners of various nationalities restored to their respective Governments. On this plan, if the negotiations fell through while the exchange was going on, say, when it was half way through, France would have got back from Britain 20,000 of her veterans, England would have received only 5,000 Britons, the balance, 15,000, being a rabble of Spanish, Portuguese, and Italian levies of practically no value, and this contention Buonaparte held to, although it was his opinion expressed a few years later “that while as a fighting unit, you might set against one Frenchman one Englishman, you would require two Prussian, Dutch, or soldiers of the Confederation.”

Buonaparte, referring to the failure of these negotiations, accounted for his firmness by his want of faith in the British, and his conviction that when they got their 10,000 countrymen back, they would find some excuse to stop the further exchange. Could we, on our part, after the unfair conduct of the exchanges, in the early part of the war, instances of which with the Norman Cross prisoners have been given, rely on the French Government carrying out in good faith even its own scheme, which on the face of it showed a disregard of British rights. 108 The negotiations fell through, and the great bulk of the prisoners at Norman Cross had to drag out their weary life until the abdication of Buonaparte and his retirement to Elba in 1814.

CHAPTER XI

BRITISH PRISONERS IN FRANCE—VERDUN—NARRATIVE OF THE REV. J. HOPKINSON

Oh, to be in England,Now that April’s there,And whoever wakes in EnglandSees, some morning unaware,That the lowest boughs and the brushwood sheaf,Round the Elm tree bole are in tiny leaf,While the Chaffinch sings in the orchard bough,In England—now.Browning.It has been necessary in the preceding chapters to allude occasionally to the English prisoners in France, and a short chapter on their experiences may be deemed not irrelevant to the scheme of this little history. The author having in his boyhood been personally acquainted with the Rev. John Hopkinson, Rector of Alwalton, near Peterborough, who had been, from February 1804 to April 1814, a prisoner of war in France, will avail himself of the kind permission of this gentleman’s son, the Rev. W. Hopkinson, J.P., of Sutton Grange, Northamptonshire, and commence the chapter with a narrative of his experiences which Mr. J. Hopkinson had himself written, and which was found among his papers after his death in 1853.

The prison at Verdun, where Mr. Hopkinson was confined at times closely, at others on parole, was occupied by the subjects of Great Britain and her allies, the British being the great majority. The prisoners were of the same class as those who were allowed on parole in Britain and who were distributed either in special prisons such as Norman Cross or in parties, which might vary from a few units to 300 or more, in one of the towns enumerated in the footnote, Chapter X, p. 192.

Mr. Hopkinson was the son of the vicar of Morton, near Bourne in Lincolnshire. He was born in 1782 within three miles of the home of Hereward the Wake, and early in life he showed that he was endowed with some of that hero’s spirit—a spirit too adventurous for the quiet parsonage. After various experiences, commencing with his following as a child a recruiting party, and joining it as a drummer boy, he entered His Majesty’s service on the 5th March 1803 as a cadet (first-class volunteer) on board the frigate Hussar. This vessel, after some brushes with the enemy while cruising in the Mediterranean, was wrecked off the Isle of Saints on the Coast of France. Mr. Hopkinson’s experiences in this misfortune and up to the date of his entering Verdun are given in his own words, while a brief biography added by his widow brings the narrative up to the date of his release after the first abdication of Buonaparte, and his arrival in England in April 1814, simultaneously with the evacuation of Norman Cross to be described in the next chapter.

“Monday night, February 6th, 1804, weighed from Ares Bay near Ferrol, bound to England with despatches, made sail and worked out of Ferrol Bay. Tuesday, Fresh breezes for the best part of the day from the Rd. Wednesday the 8th—At noon by account Ushant bore from us N. 24 Lat: distant 109 miles, towards the Evening the breeze died away and became variable, but sprung up from the Southward and Westward at 6 o’clock. At 8 o’clock P.M. Ushant distant 50 miles, went on deck to keep my watch, the ship steering N.E. by E. by the Captain’s orders, who had also left orders to be called at 12 o’clock. The breeze continued, freshening considerably till 10 o’clock, when I was obliged to leave the deck to attend the Gunner in transporting powder, which duty we were on the point of finishing at 11.30, when the ship struck with great violence, put the lights out immediately and got on deck as soon as possible, where we found every person struck with terror, it being the general opinion, that the violent shock which they had felt proceeded from the powder magazine and expecting every moment to be their last; but when relieved from this dreadful impression by our appearing on deck, they immediately let go the small bower anchor and proceeded to take in sail.

“It appears that at the time the ship struck she was going between 8 and 9 knots, which hurried her on the rocks with such violence, that the tiller was carried away, the rudder unhung from the stern post, and a great hole made somewhere under the starboard bow, and after beating over the reef, the ship was running on an immense rock, which was prevented by the letting go of the anchor. As soon as the sails were furled we manned the pumps, and found the ship made at the rate of 15 feet water per hour. At 12, on the turning of the tide, the ship tailed on the rocks and struck with dreadful violence at times: let go the best bower anchor, scuttled the spirit room bulkhead to clear the water from aft. Fired minute guns and rockets at times, with the signal of distress: discovered a light on our starboard beam, a small island, but no one on board knew for a certainty where we were, employed all night at the pumps, and clearing away booms to get spars out to shore the ship up, as also to be in readiness to get the boats out if requisite.

“At 6 a.m. daylight discovered to us our situation, that we were upon a reef of rocks, extending from the island of Saints Westward in to the Atlantic, ‘Hinc atque hinc vastœ rupes’ at a distance of half a mile from the island. Got the shores out on the starboard side, lowered the cutter, and sent the master to sound for a passage among the innumerable rocks with which we were perfectly surrounded. At 7 the ship had gained one foot on the pumps, and during the last hour had 3 ft. 8 inches water in the hold, at 8 the master returned, and had only found a narrow passage with 10 feet water in the deepest part, which report together with every appearance of an approaching gale from the S.W. confirmed the opinion already formed, that we were precluded from every means of saving the ship. In consequence of which Capt. W. ordered the third division of seamen, and all the marines to land, and take possession of the island, in order to secure a retreat, and, if possible, the means of escape from the enemy. Got the boats out and landed the force above mentioned, being given to understand by the Gunner, who pretended to know the place, that it was a Military Station, and consequently, that we should meet with some resistance; but on arriving at the town found it only occupied by a few fishermen. Took possession of the church and made use of it as barracks for our ship’s company, whom we were occupied landing all the remaining part of the day, the current running with such rapidity between the rocks, that it was with the greatest difficulty and danger the boats could go to and fro. This was however happily effected without any accident; landed also three days’ provisions: ‘Tum celerem corruptam undis cerealiaque arma expediunt.’

“The wind all this day very boisterous from the S.W. with heavy rain, and every symptom of an approaching gale. Towards dusk, mustered the ship’s company, put them all into the Church and placed sentries over them, patrol’d the island all night, employed all the forenoon in burning the remnants of the ship, and fitting 13 sail of fishing boats, besides our Captain’s barge for our departure for England: the Captain’s boat distinguished by the Union Jack being destined to lead the way, and the other boats being formed into three divisions, commanded by the three Lieuts. with distinguishing names to follow in due order, the wind being fresh from the S.W.

“I may now begin to speak on a smaller scale, and only mention the proceedings of our own boat, with occasional remarks concerning the others. At noon, made sail from the Island, scudding under a fore and main sail alternately. At 4, finding the wind heading us fast, hauled on a wind to endeavour to keep off shore as much as possible, in order to get on the Beniquet if necessary, most of the other boats being in sight, the Captain’s just perceptible ahead. At 6, strong gales and squally, with rain and a tremendous heavy sea. Observed the Hay stacks on our lee beam: at 6.30, observed the oars and rowlock of the Captain’s barge floating to leeward which made us fear, ‘fraguntur remi,’ that he had perished. At 7, passed to leeward of the Parquet, which was very perceptible by the roaring and breaking of the sea, which was awful in the extreme.

“At 9, finding we could not weather St. Matthew’s, Mr. B. and the commanding Officer, ‘O socii passi graviora,’ of the boat addressed the crew, to consult concerning the best means of saving their lives, when it was unanimously decided to bear up for Brest, a dire, but unavoidable alternative. Employed continually pumping and baling the boat, over which the seas were continually breaking. At 10.30, spoke one of our boats, which was laying broadside to the seas dismasted, but could not give her any assistance. At 11 were hailed by the batteries, did not answer, but hauled close to the land; they fired at us several times, but without effect.

“At 11.30 ran alongside a line of Battle ship which caused an immediate uproar on board of her. They threw us a rope, but no one could hold it, on account of the cold and numbed state of all on board. The ship (which proved to be the Foudroyant) immediately manned her boat, and boarded us, and when the Officer understood who we were, he took us out of our boat, which he left moored to a buoy, and put us on board of L’Indienne frigate, the tide running too strong to regain his own ship. We were uncommonly well treated on board, one of the Mids made me change my clothes, and they gave us every refreshment in their power, after which I fell asleep till 3 a.m., when I was called to go on board the Foudroyant, the ship to which we had first surrendered. Here the Captain behaved to us in a handsomer way than we had any right to expect, giving up his own cabin for our use, furnishing us with linen, and every delicacy he had to offer. Got up at 6 and walked the deck with the French midshipmen, who gave me to understand that our countrymen had been coming in the harbour at all hours of the night, and they also told me that our boat had gone to the bottom. After breakfast with the Capt. he expressed the greatest concern at being obliged to send us on board the Flagship. We accordingly at 10 o’clock left him, impressed with the highest sense of his humanity and generosity.

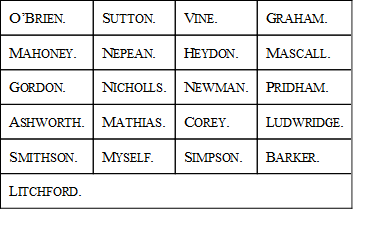

“On our arrival on board the Flagship we had the inexpressible pleasure of meeting with a great many of our shipmates, of whose fate till then we were totally ignorant. After dining on board, we were all ordered on shore to be confined in the hospital, until the will of the Minister of War should be known. When in the Hospital we were mustered and found that the following were missing, Capt. W. and his crew making altogether 12, whom some seamen affirmed to have seen sink, which statement was partly corroborated by our having seen his oars. Mr. Gordon, midshipman and his crew, 15 in number, who, when last seen, were a long way to windward, and Mr. Thomas the En. who was drowned in landing. The next day to our great astonishment Mr. Gordon and his crew joined us and gave us slight reasons to hope that Capt. W. had reached the Beniquet.

“During the next week we were visited by the Commissary of War, who told us that the Minister of War had given orders for our being removed to Verdun, and advised us to prepare as much as possible for our march to that place; he also had the goodness to send us a banker who gave money for bills on the Government, a thing that was very acceptable, as by the length of time we had been at sea all our Lieuts. had some pay due, and they supplied the Midshipmen with small sums, which, added to the allowance of the French, 1s. 3d. per diem, might enable us to travel very comfortably.