полная версия

полная версияThe Depot for Prisoners of War at Norman Cross, Huntingdonshire. 1796 to 1816

[200] Basil Thomson, loc. cit., pp. 28, 29.

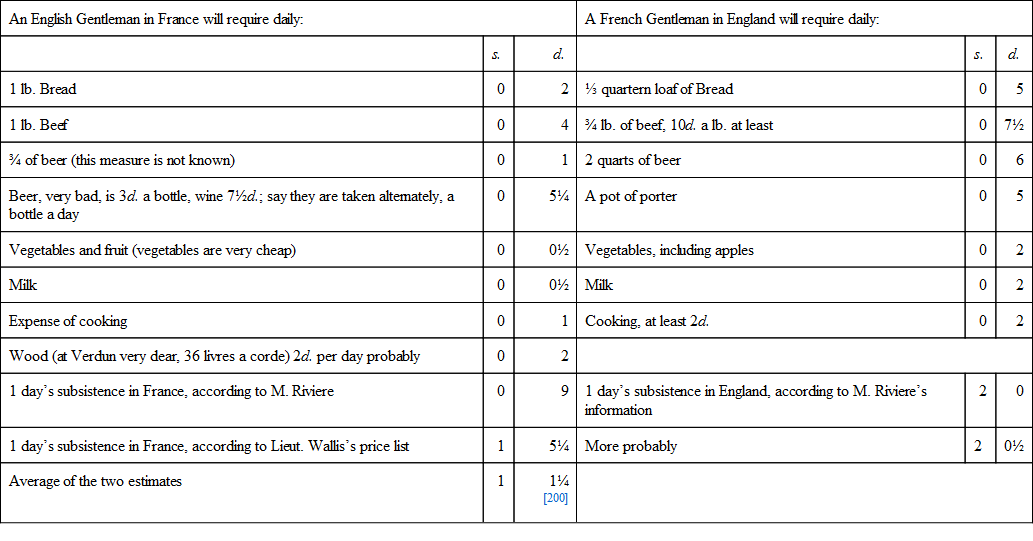

It therefore appeared clear that the least an officer could live on was 2s. a day in England and 1s. a day in France. To double the allowance to the French officers in England would, it was estimated, cost the Government £43,823, and ultimately it was decided to increase the allowance to 2s. for the higher ranks, coming down to 1s. 8d. in the lower, at an increased cost of £28,000 a year. When invalided, the prisoners received an extra allowance, and were attended by doctors practising in their neighbourhood selected by, and paid by, the Government. Their allowance was doubled when a nurse was required. These extra charges were borne by the Commissioners for the Care of the Sick and Hurt, not by the Transport Board.

The majority of the officers on parole were not entirely dependent on the allowance received from the British Government, their income being supplemented by remittances sent from France.

Several of the officers of high rank, and other prisoners whose means enabled them to do so, sent for their wives and lived comfortably in lodgings. Judging from the traditions of the Norman Cross district, and from the literature of the period, the presence of the prisoners on parole made but little change in the social life of the towns and villages in which they were quartered, not sufficient to leave an enduring impression. This is strange, for the presence of 100 foreigners of varying social position in and round about a quiet little cathedral city, such as Peterborough was a century ago, must certainly have modified the usual routine of the social life of its citizens, and of the dwellers in the neighbouring villages in which some of the prisoners lodged.

Although the bitter antagonism which existed between the French and the British during this long war would militate against it, there is no doubt that occasionally the prisoners on parole visited and formed friendships, and even attachments, among their neighbours according to their degree. This general statement made to the writer by his parents and other nonagenarians is borne out by the marriages to be mentioned directly, but although the writer has lived in Peterborough, excepting the few years when his education took him away, for three-quarters of a century, he does not recollect ever to have heard of any special instance of the survival of such a friendship in the city or in the immediate neighbourhood of Norman Cross, excepting those to be detailed when the marriages of the prisoners are dealt with.

It has been thought not irrelevant to the history of Norman Cross to devote the succeeding chapter to the subject of the English Prisoners in France, and it will be there seen that in the letter written by Lieut. Tucker from Verdun, he specially says, “there is no society between the English and the French.”

When in 1814 Napoleon abdicated, and the Treaty of Paris was signed on the 30th May, some 70,000 French prisoners, of whom nearly 4,000 were out on parole, together with hundreds of émigrés, left our shores. These friendships and close associations were abruptly cut short, and the foreign element in British Society appears to have been speedily forgotten. The intimacies which were kept up, of which we read in the biographies and family archives of those who lived in the first half of the last century, were almost all between the British and the French émigré, not between the British and the prisoners on parole; they were between persons who, although of different nationalities, agreed in their political sympathies, and who were equally opposed to the existing French Government.

Between 1793 and 1814 about 200,000 Frenchmen and other foreigners (at various periods, not all at one time), either in durance or on parole, spent a longer or shorter period of their lives in Great Britain. In the second period of the war (1803–15) there were 122,440, and of these probably 4,000 at least were out on parole, including in this estimate not only the commissioned officers, but also the large number of officers of privateers and of civilians of various occupations who were all reckoned as prisoners of war. 98

A comparison of the Census Returns and the official returns as to prisoners of war for the year 1810 justifies the conclusion that about 2 per cent. of the adult males in Great Britain of the average age of the prisoners must have been Frenchmen. Of this 2 per cent., the great majority were, as has been already stated, in confinement; but as those on parole were not scattered broadcast throughout the country, but were concentrated in the various towns enumerated in the footnote to page 192, they would in these towns constitute a far larger proportion than 2 per cent. of the men of their own age. In Peterborough the 100 parole prisoners would be about 15 per cent. of their contemporaries in the town and neighbourhood. It is strange that this considerable element of French in the society of that period figures so little in the pages of contemporary authors who deal with social matters. In explanation it must be borne in mind that the allowance of the Government to the prisoners on parole was only sufficient for a bare living, and that, except in the case of those with good private means, these officers would have to be very economical in their choice of lodgings, and would be thrown chiefly into the society of persons who were by their circumstances compelled to let cheap lodgings. The prisoners would form a little circle among themselves.

Mr. John T. Thorp has with infinite pains gone into the question of how far Free Masonry brought the parole prisoners into association with their brethren of the craft. 99 The result of his investigations is that, although in eleven of the towns in which parole prisoners were detained—viz. Abergavenny, Ashby-de-la-Zouch, Leek, Melrose, Northampton, Plymouth, Sanquhar, Tiverton, Penicuik, Wantage, and Wincanton—French Lodges were established by the prisoners resident in the towns or their neighbourhood, only in four is there any evidence of association with British masons. In Abergavenny two English became members of the Lodge. In Melrose the members of the French Lodge joined with the Brethren of the Scotch Lodge in the ceremonial of the laying of the first stone of a public reservoir, and among the archives of the Scotch Lodge was a memorial presented by twenty of the members of the French Lodge expressing their gratitude for the fraternal manner in which they had uniformly been treated by the Brethren of the Melrose Lodge.

In Wantage, the Lodge “Cours unis” was formed by the prisoners, and when seven members were transferred to Kelso, it is recorded that they were received as visitors by the Scotch Lodge in that town.

At Wincanton (“La Paix désirée”) two certificates were granted to Englishmen, one as a joining member and the other as an initiate.

Very little more evidence is found in the minutes of the English Lodges. At Ashburton is the record of the Initiation of a Frenchman. At Selkirk twenty-three parole prisoners who were masons were enrolled as members of the Lodge, and they were allowed the use of the Lodge Room for their own business and ceremonies.

At Northampton, in the neighbouring county to that in which Norman Cross is situated, a French Lodge (“La Bonne Union”) was established, but there is no tradition of any association with the English Brethren.

At Ashby-de-la-Zouch a French Lodge was formed, but there is no record of any intercourse with the English Brethren. Ashby was a large depot for parole prisoners, some 200 being located in the town and neighbourhood, and there is a tradition that the French Lodge of Freemasons gave a ball to which they invited many of the inhabitants.

One reason why the Brethren of the French and English nations apparently associated to such a small extent, is that the British masons would, as a rule, regard the French Lodges as irregular and self-constituted, they having no mandate from the Grandmaster of England or Scotland.

In Peterborough there is no record or tradition of a French Lodge.

Mr. Thorp, in the little history from which these facts are drawn, mentions the marriage of a member of the French Lodge at Ashby-de-la-Zouch, Brother Louis Jan to a Miss Edwards, in 1809. The couple went to France in 1814, returned to England for some years, but went back to Rouen, where M. Jan died. His widow came back to Ashby, where she supported herself and her children by teaching French. She died in 1867.

As regards the parole prisoners whose headquarters were at Peterborough, a careful search through the marriage register of St. John’s Church has failed to discover an entry of any marriage which can be identified as that of a French prisoner and English girl; but in the years 1800–01 five marriages between Dutch prisoners and English girls were celebrated in the church and duly registered.

The first three bridegrooms were young officers, who were married on the eve of their restoration to liberty under the terms of the Convention of Alkmaar. From the register of Dutch Prisoners of War in the Record Office, we have been able to identify these bridegrooms. In the Parish Church Register there is absolutely no hint that the bridegrooms were prisoners of war. The names only are given, without any description, although the statement that there are entries of French prisoners, designated as such, in this marriage register having been once made, has been adopted time after time by writers and lecturers on this subject.

1. On the 17th February 1800, Albertus Coeymans was married to Ann Whitwell. Witnesses who signed the register, B. Pletsz and James Gibbs. James Gibbs appears to have been the Parish Clerk, who usually witnessed the marriages. From the register in the Record Office we find that Albertus Coeymans was 2nd Lieutenant in the Furie, was captured when the ship was taken, received at Norman Cross 19th November 1798, and “discharged to Holland” 19th February 1800. The witness B. Pletsz was Captain of the Furie, and was received at Norman Cross on the same date as the Lieutenant.

2. On the 17th February 1800, Adrian Roeland Robberts Roelans was married to Mary Kingston. Witnesses, Joseph Little and James Gibbs. Mr. Roelans was a midshipman on the Jupiter, and was received at Norman Cross, with others of the captured crew, on the 4th November 1797, being released on parole twelve days after his reception. It is interesting to note that the witness at this wedding was not another Dutch officer, but Mr. Joseph Little of Thorpe, in which hamlet Miss Kingston resided. That the marriage of his friend was satisfactory to this witness, and that the intimacy between them was kept up after the liberation of the midshipman under the Alkmaar Cartel, may be accepted as established by an entry in the register nine years later of the marriage of Joseph Little of Thorpe to Mary Roelans, probably the sister of his friend the midshipman captured on the Jupiter.

Mr. Joseph Little remained at home with his Dutch bride, and as far as can be traced through the complicated connections of the large clan of Littles, the blood of Roelans still runs in the blood of several of them. A brother of Mr. Little’s had married a sister of the Miss Kingston who became the wife of Cadet Roelans, thus creating another link in the marriage connection of the Dutch Roelans and the Northamptonshire Littles.

3. On the 18th February 1800, Charles Peter Vanderaa married Lucy Rose. Witnesses to the marriage, J. Ysbrands and James Gibbs. Mr. Vanderaa was Lieutenant on a brig-of-war which was captured. He was received at Peterborough on parole on 11th June 1798, and was released on 19th February 1800. The witness J. Ysbrands was the Captain of the Courier, taken prisoner and received at Peterborough on parole 21st June 1798, released 19th February 1800 in accordance with the Alkmaar Convention.

4. After an interval of six months, on 20th August 1800, is the entry of the marriage of Antoni Staring to Nancy Rose. Witnesses, E. B. Knogz and James Gibbs. The bridegroom was Captain on the Duyffe man-of-war. He was received 27th May 1800, released 26th August, having been married on the day previous. The witness E. B. Knogz was surgeon on the Duyffe, and was received at Peterborough and released on the same day as the captain.

5. The fifth marriage of the Dutch prisoners was that of Berthold Johannas Justin Wyeth to Sarah Wotton. These marriages were all by licence and not by banns. In this case the entry is “Licence with consent of Parents,” but this by no means implies that the other marriages took place without such consent; the addition of these words depended upon the habit of the officiating minister. The witness was B. Pletsz. Mr. Wyeth was 2nd Lieutenant of the Furie, and was received on parole on 19th November 1798. He was not exchanged under the Alkmaar Cartel, but remained a prisoner until the 16th October 1801. 100

As regards the absence of any evidence of the marriage of the French prisoners and British women, it must be remembered that the vast majority of the French were Roman Catholics, and that mixed marriages of members of that Church with Protestants were discouraged by the authorities of both Churches alike. There existed also throughout these years a fierce animosity between the French and the English, and when it is added that the French Government did not acknowledge the legality of such marriages, so that in many instances the unfortunate wives when they returned with their husbands at the close of the war were not allowed to land, we can understand that almost irresistible pressure would be exercised to prevent these unions, and that intimacies and flirtations which might ripen into love would very probably be strongly discouraged.

One instance of an attachment between a French prisoner confined at Norman Cross and an English girl, and their subsequent marriage, was that of Jean Marie Philippe Habart to Elizabeth Snow, of Stilton. In the prison register we find Jean Habart entered as a sailor, captured off Calais, 20th June 1803, in L’Abondance, a small vessel of ten tons. He was put on board L’Immortalité, and from her transferred to the prison ship Sandwich; was sent thence to Norman Cross, being received 27th August 1803. He acted as baker to Mr. Lindsay, the contractor, and was discharged on 20th June 1811. This official statement differs from the family tradition in two points only: the register says (probably incorrectly) that he was a sailor, the family that he was only temporarily on the boat fishing; the register says that he was freed on 20th June 1811, his granddaughter believed that he was freed on the emptying of the prison in 1814 (the register in this case is doubtless correct). His granddaughter’s account is, that M. Jean M. P. Habart was the son of a gunsmith in a good position in a town on the north coast of France, and that he was captured while fishing off the coast, and was imprisoned at Norman Cross. There, as we learn from the register, not being a combatant, but a civilian prisoner of war, he was employed as baker to the contractor.

His future wife, the daughter of a farmer in Stilton, was in the habit of bringing up the milk bought for the prisoners’ use, and she would probably have frequent interviews with the contractor’s assistant, and as her granddaughter says, “she fell in love with him.” The attachment was mutual, and when after his release he returned to France, he left his heart behind him. During his imprisonment his father had died, leaving property for his children, 101 and Jean, when he had realised his share, returned to England, married Miss Snow, and settled in business, as a baker and corn merchant, in Stilton. The years of his imprisonment had been sweetened by love, but his end was a tragic one. On 24th January 1840, forty-three years after he passed through the prison gates and first saw the hated caserns and fenced courts of Norman Cross, he was killed within sight of the fields on which they stood.

He was returning from a round, which he had been making to collect money from his customers, and it is supposed that at an inn in Peterborough he had shown his well-filled purse, and was followed on the Norman Cross Road to the spot about three miles from Peterborough, where he was found with his head battered in and his pockets rifled, his empty purse being found some time after in an adjacent field. 102

Such histories as have been here given from the writer’s long and intimate knowledge of the locality might doubtless be collected in the neighbourhood of other prisons, but the danger of assuming that the mere occurrence of French names in the neighbourhood of a depot “still speak of the old war time” has already been dealt with in Chap. IV, p. 59, footnote.

The parole-breakers who managed to escape, varied from the humblest and poorest of the non-combatants, who had to pass through many hardships and trying adventures before securing their freedom, to men in the position and affluence of General Lefebre, who, in May 1812, accompanied by his wife, escaped from Cheltenham. He personated a German count; his wife, in boy’s clothes, passed for his son, and his aide-de-camp acted as valet. They put up at an hotel in Jermyn Street, got a passport, and reached Dover in style, whence they were conveyed to the French coast. From France he wrote an insolent letter to the English Government in justification of his breach of parole.

A slightly different version was that he reached London as a Russian General Officer, with two aides-de-camp, one of whom was his wife dressed in military costume; all conversed in German.

The conduct of the officers on parole both as regards the breaking of their parole and their general orderly behaviour, varied greatly in different districts, as also did the attitude of the surrounding population towards the prisoners when they attempted to escape. A population which for centuries had been accustomed to receive the benefits of, and to ignore or assist in, the trade of smuggling, would view the attempt to escape in a different light to that in which the quiet agricultural population of the Midlands and East Anglia would regard it.

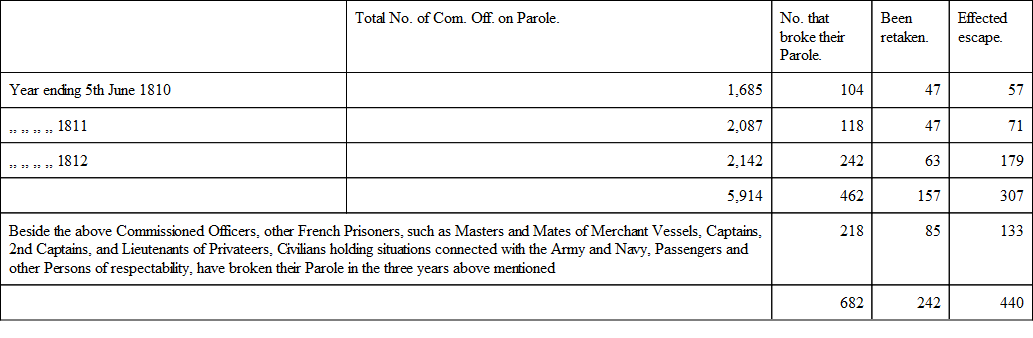

The father of the writer, who had seen and heard much of the prisoners of war during his boyhood in Perth, said that while the British prisoners in France contrasted unfavourably with the French in England, because they showed none of the skill and industry which enabled the French to produce work, by the sale of which they raised large sums of money, the French displayed a moral inferiority by the frequency with which they broke their parole, that is, disregarded the pledge given on their word of honour. The following return shows that in the three years included in the table, about one in every ten of the officers of the army and navy who were on parole broke their pledge. The proportion cannot be calculated in the case of other persons of promiscuous occupations, as the table does not give the total number of the prisoners of this class, but only the actual number, 218, who broke their parole.

Transport Office,25th June 1812.NUMBER OF ALL FRENCH COMMISSIONED OFFICERS, PRISONERS OF WAR, ON PAROLE IN GREAT BRITAIN

N.B.—The numbers stated in this Account include those Persons only who have actually absconded from the places appointed for their Residence.

A considerable number of Officers have been ordered into confinement, for various other breaches of their Parole Engagements.

(Signed) Rup. George, J. Bowen, J. Douglas. 103

There are no records to show that the conduct of those on parole from Norman Cross, whether they were lodged in the prison or in the neighbouring towns and villages, was otherwise than that of gentlemen, and the records of broken parole are very scanty.

The prisoners reported themselves regularly twice a week, as the custom was, to the agent at Peterborough, when he paid each his allowance; they kept within bounds, and returned to their lodgings within the prescribed hours.

No such amusing incident is told of any of them, as that told of the French officer at Jedburgh, who, being an antiquarian, soon exhausted all places of interest within the circle of one mile radius, beyond which the country was out of bounds. Being told of a most interesting building a little beyond the first milestone from the town, he nobly struggled against the longing to go beyond that stone, and he was rewarded for his strict adherence to his “Parole d’honneur,” for an inspiration came to him, and, borrowing a spade and a wheel-barrow, he laboriously dug up the milestone, and, putting it into his wheel-barrow, carted it beyond the spot of his heart’s desire, and, replanting it there, revelled in his research with unspotted honour. 104

Mr. Palmer, who was born in 1812, three years before Waterloo, and lived on the North Road in a pretty farmhouse at Stibbington, opposite the first milestone from Wansford, told the writer that when his grandfather took the farm in 1797, the house was the Wheat Sheaf, a coaching inn, which came to grief in 1841, killed by the railways, the house being rechristened The Road Side Farm. The milestone was the outside limit for those on parole who were quartered at Wansford (it was more than five miles from Norman Cross), and Mr. Palmer pointed out the small room which the prisoners used for smoking and recreation. His grandmother was renowned for cooking, and could even please the fastidious taste of the French officers. Mr. Palmer’s little baby eyes must often have looked with wonder at the prisoners, talking in a language he could not comprehend, and he must have gazed after them with childish curiosity, as they turned—after a longing look into the forbidden land beyond—to retrace their steps and reach their lodging within the time prescribed.

One point should be noted, that in searching the records to ascertain the various regiments quartered at Norman Cross, in order to fix the date of Macgregor’s plan, it was incidentally found that while the West Kent Regiment was quartered there in 1813, detachments lay at Peterborough, Whittlesea, and other neighbouring towns; these were probably for the purpose of acting if any difficulty arose with the prisoners on parole. The punishment for breaking parole was, as already mentioned, if the prisoner were recaptured, very severe. Not only was the ration allowance reduced until all expenses incurred in the capture were paid off, but committal to one of the prisons or to the hulks was also inflicted.

The local histories of various towns where depots for prisoners of war on parole were established have been consulted with very disappointing results. There must be local sources of information in some of the ninety-one towns enumerated in the footnote at page 192, and any future writer on the subject of the prisoners of war confined in Britain between 1793–1814 is advised, if he has leisure for research, to seek information from these districts. The following condensed notes on the prisoners on parole at Leek are given as an example of what took place in one of the towns where facts have been put on record in a local history. Unfortunately no such record is available for any of the towns in the Norman Cross district. It was only within the last fifty years that the following scanty information was collected and recorded. Sleigh’s History of Leek was published in 1862, only forty-seven years after Waterloo, when Mr. Neau was still alive, and when the children of the few parole prisoners who settled in Leek when their captivity was at an end must have been still only middle-aged people, and yet in this first edition the prisoners are not mentioned.

In 1883 there were published, in Notes and Queries, 105 some interesting paragraphs dealing with the subject of the prisoners of war, and these were embodied in the second edition of Sleigh’s Leek, published in 1883. 106 From these paragraphs the following condensed notes are culled. The officers received all courtesy and hospitality from the principal inhabitants of the town and neighbourhood. Those with good private means used to dine out in full uniform, each with his body servant stationed behind his chair. It is also stated that these prisoners used to go out early and collect snails as a bonne-bouche for breakfast. There were some men of mark among them. Of these, three died during their captivity, and were buried with many other parole prisoners in the God’s acre attached to the old church. There are memorial stones to Joseph Dobee, Captain of La Sophie, ob. 2nd December 1811, æt. 54; to Chevalier J. Baptiste Mullot, Captain of the 72nd French Regiment, ob. 9th June 1811, æt. 43; and to Charles Luneand, Captain in the French Navy, ob. 4th March 1822. The latter officer must have settled in Leek, the date of his death being seven years after Waterloo.