полная версия

полная версияThe Depot for Prisoners of War at Norman Cross, Huntingdonshire. 1796 to 1816

68

Vol. ix., chap. lxiv., par. 127.

69

This information Alison gave from his own personal recollection. I can confirm his account from what I have been told by my father, who in his sixteenth and seventeenth years was living in Perth, and was in the habit of going to the prison to take lessons in French and in fencing from one of the officers confined there.—T. J. W.

70

Curiously this article does not appear in Poole’s original Index, but in the second supplement under “Banker’s Notes.”

71

These were a part of the troops who in 1797 landed at Fishguard to invade England through Wales. This long-planned invasion ended in a fiasco.

72

Laws, Little England Beyond Wales, pp. 373–4.

73

Legends of Huntingdonshire, W. B. Saunders.

74

W. H. Bernard Saunders, loc. cit., 1888.

75

Archæologia Cantiana, ix.–xciii.

76

Chambers’ Miscellany, No. 92, vol. vi., p. 32, New Edition. Story of a French Prisoner of War in England.

77

Story of Dartmoor Prison, pp. 32, 33.

78

Aperçu du Traitement qu’éprouvent les Prisonniers de Guerre français en Angleterre: Paris, 1813.

79

Appendix E.

80

Naval Chronicle, xxviii., 282.

81

The expense of the prisoners’ clothing, provision, and supervision was £1,000 a day exclusive of buildings.—Naval Chronicle, xxxiv., 460.

82

Appendix F. Full return, with names, etc., of the hospital staff.

83

The following, copied from a loose paper lying between the pages of Reg. 628 at the Record Office, is evidently an answer to the inquiries of a prisoner’s friends, made ten years after his death. It gives a chance insight into one of the duties of the agent, and is evidence that the French were at least treated with courtesy:

“Le Soussigné Agent du Gouvernement Britannique Chargé du soin et de la Surveillance des Prisonniers de Guerre au Dépôt de Norman Cross, Certifie que le Nommé Vincent Fontaine, natif de Veli, Pris à Bord du transport La Sophie, en qualité de soldat, entre en Prison au Dépôt de Norman Cross le 25 Septembre 1804, est mort à l’hospital du susdit Dépôt le Vingt trois mars, mil huit cent huit, âgé de Trente ans et demi, ainsi qu’il couste par les Registres de la Prison.

“En foi de quoi j’ai délivré le Présent Extrait pour servir à qui de Raison.

“Norman Cross le 1er Juin 1814.

“(Signed) W. Hanwell, Capt. R.N., Agent.”[Translation]“The Undersigned Agent of the British Government in charge of the care and the superintendence of the Prisoners of War at the Depot of the Norman Cross, certifies that the named Vincent Fontaine, native of Veli, taken on board the transport La Sophie, as being a soldier, entered into the Prison at the Depot of Norman Cross on the 25th September 1804, died in the Hospital of the above-mentioned Depot, 23rd March 1808, Age 30½ years, as shown by the Prison Registers.

“In Witness whereof I have delivered the present Extract to be used by Whom it may concern.

“Norman Cross, 1st June 1814.

“(Signed) W. Hanwell, Capt. R.N., Agent.”Vincent Fontaine was the only prisoner who died during the week ending 27th March 1808. The certificate was signed by Thos. Pressland, the agent at that date.

84

Notes and Queries, Ser. ii., v. 204.

85

Appendix G.—Letter enclosing short autobiography from the Bishop of Moulins to Earl Fitzwilliam. Reply from Earl Fitzwilliam and correspondence between his lordship and Lord Mulgrave, etc.

86

The French Prisoners of Norman Cross. A tale by the Rev. Arthur Brown, Rector of Catfield, Norfolk. (Hodder Brothers.)

87

This house is selected by tradition as that of the Bishop, being the one most suited to a wealthy ecclesiastic of high rank. The Bishop’s letters are dated from the Bell Inn, where he probably could live, en pension, on what was left out of his £240 a year, after paying the interest due to the money-lenders.

88

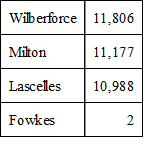

This was a remarkable election, and created immense excitement at the time. There had been no contested election for forty-six years, and in 1807 there were four candidates for the two seats. One, a Mr. Fowkes, received two votes. William Wilberforce, the great advocate for the abolition of slavery, led all the way; the real contest was between Milton and Lascelles. Wilberforce’s expenses were largely met by subscription; the cost to the other two was enormous. The Recorder of Leeds said, “The yellow had not only been in the hats, but had also been in the pockets of the voters for Lord Milton.” The state of the poll at the end was:

Smith, Parliaments of England, ii. 136, 140. The Times, 26th, 28th, 30th May, 2nd, 4th, 6th June 1807.

Wm. Wilberforce, Esq.; Rt. Hon. Chas. Wm. Wentworth, commonly called Viscount Milton; Hon. Henry Lascelles.

89

“Ces jeunes captifs furent instruits par les soins de M. l’Évêque de Moulins.”

90

As these pages are passing through the press, the opportunity offers of seeing through the observant eyes of Mrs. Larpent the Bishop as he was when she met him in London, about 1804, and for the “man with a fine presence” we must substitute the “little deformed lively man,” described in that lady’s diary, “Nineteenth Century and After,” No. 438, August 1913, p. 318.

91

Appendix G.

92

Mémoire des Évêques français résidant à Londres qui n’ont pas donné leur démission, Londres, May 1802; Biographie des Hommes vivant, 1818, Paris; Biographie des Contemporains, Paris.

93

Mémoire des Évêques français résidant à Londres, pp. 108, 217, 284.

94

The only reference by his French biographer to his work at Norman Cross, which looms so large in this book, is that “he is said to have visited the prisoners of war when in England.”

95

Supplement to Appendix 59, Report of the Transport Board to the House of Commons, 1798. Issued from Downing Street 6th January 1801.

96

If the commander of a privateer before lowering his flag threw overboard as many of his guns as he could, in order to prevent their falling into the hands of the enemy, and thus reduced their number below fourteen, he was no longer eligible for parole, but remained in prison.

97

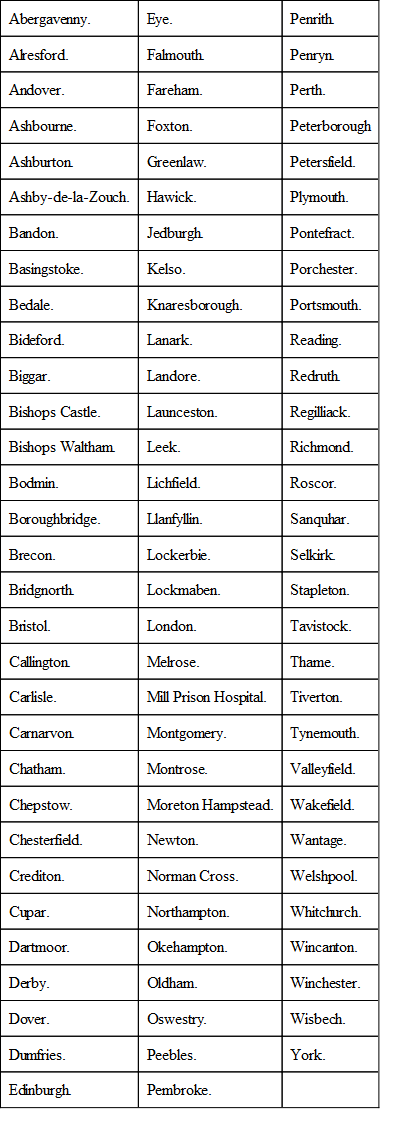

List of places where French prisoners of war were allowed on parole at different periods of the war.

98

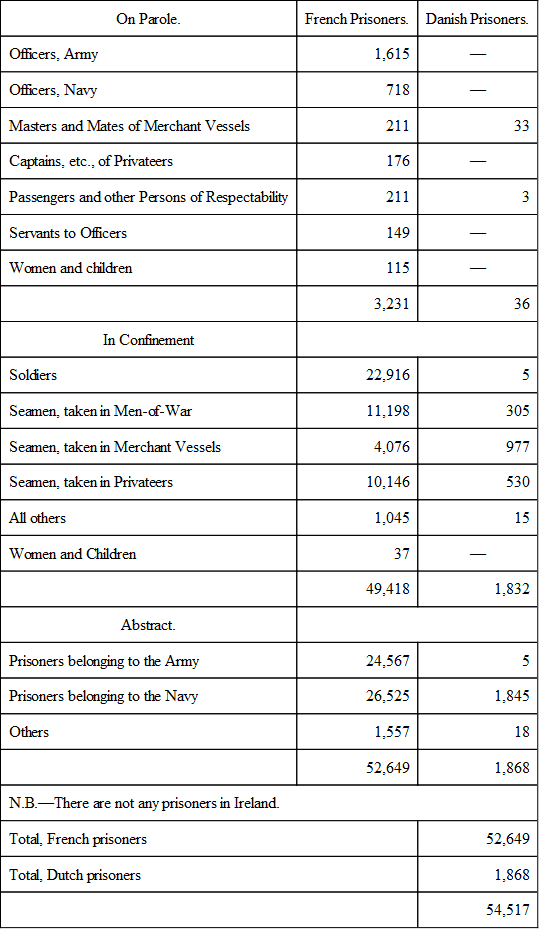

A RETURN OF THE PRISONERS OF WAR AT PRESENT IN GREAT BRITAIN

Transport Office,26th June 1812.

In reference to this return it may be here mentioned that very few of the Danes were brought to Norman Cross, either in the first period of the war, or in the second period in which this return was made.

99

French Prisoners’ Lodges, by John T. Thorp, Leicester. Printed by Bro. Geo. Gilbert, King Street, 1900.

100

Of the after history of the young men and maidens who contracted these romantic marriages I can give information in only two cases. Charles Peter Vanderaa, entered in the register of the Record Office as lieutenant on a brig-of-war, was married on the day of his release. Whether he took his wife to Holland or not, his grandson, from whom I got my information, did not know. All he knew was that his grandfather, in some capacity or other, again took to the sea, and that he died of yellow fever in Spain or one of the Spanish colonies, leaving his widow with two sons, Thomas and Peter. The widow, after his death, lived in Peterborough in very poor circumstances. The second son, Peter, I well remember earning a living as a schoolmaster in Peterborough, where he had at one time been in the police force; he married and had one daughter, who married a blacksmith named Dawson. The couple moved to London, where there may be a colony of the cadet’s descendants, recking nothing of their Dutch blood. The oldest son, Thomas Vanderaa, had two sons, one of whom I knew well. His mental capacity was not very high; he got his living as a casual, respectable gardener and handy man. He died a few years since, but I have preserved the letter in which he gave me the information about his relatives.

When in 1894 Mr. Vanderaa gave me the information about his family, he said he had a brother, who was, he believed, alive, but he did not know where he was living.

Of the descendants of the Miss Roelans, who married Mr. Joseph Little, several are living in a good social position; but the Dutch blood does not seem to have passed into the collateral branches of Moores, Buckles, and other well-known families who have intermarried with the Littles.

101

The gunsmith’s business was a good one, and remained in the family, and the grandson, M. Hubert Habart, who had succeeded to it, had an exhibit of guns in the Great Exhibition at the Crystal Palace in Hyde Park in 1851.

102

Several of M. Habart’s descendants are still alive. One of his granddaughters, Miss Habart, is my consulting-room attendant. The family of the Rev. Father Robert A. Davis, from whose copy of Macgregor’s plan the plate on p. 18 is taken, is connected by marriage with that of the Habarts.—T. J. W.

103

Parl. Paper, 1812, vol. ix., p. 223.

104

Maberly Phillips, The Connoisseur, xxvii., No. 105, May 1910.

105

Notes and Queries, ser. iv., vol. v., pp. 376, 546.

106

Sleigh, History of Leek, 2nd edn., p. 221.

107

Wellington’s Despatches.

108

This is how the naval authorities summed up the failure of the negotiations for exchange: “There is no fixing the French Government to any basis of exchange. Every concession on our part has produced fresh demands. We have about 50,000 prisoners of war in England, in France there are about 12,000, two-thirds of whom are not prisoners, but détenus, many of them women and children. Even these our Government were willing to exchange, when the French Government proposed that their 50,000 should be sent over en masse, for the 12,000, and then afterwards the Spaniards would be released. This would enable it to man twenty-five sail of the line, and still retain the Spaniards, our allies, in his hands.”—Naval Chronicle, vol. xxiv., p. 327.

109

Appendix H.

110

A good description of Verdun in 1811 will be found in the Narrative of a Forced Journey through Spain and France an a Prisoner of War in the Years 1810 to 1814, by Major-Gen. Lord Blanfrey. In 2 vols. 1814. Vol. ii., chaps, xxxvi.-xxxvii., good account, viii., ix., xl., xli., xlii., xliii., xliv.

The author says he was confined for seven weeks as a hostage to prevent the English Government from punishing a French officer who had projected a rising of the French prisoners in England.

111

Naval Chronicle, xiv., 17; xv., 122; xvi., 108; xvii., 108; Douglas Jerrold, The Prisoner of War, 1842; A Picture of Verdun, or the English detained in France, from the Portfolio of a Détenue, 1810, 2 vols.; Letters from France, written in the Years 1803 and 1804, including a Particular Account of Verdun and the Situation of the British Captives in that City, 2 vols. 1806; Chambers’ Journal of Literature, Science, and Art, 1854, vol. i., p. 330.

112

Few of the Danes were brought to Norman Cross, either at this period of the war or in the second period when there were a considerable number confined in Great Britain. From a return made to the House of Commons in 1812, it appears that of 54,508 prisoners confined at the various depots, 52,640 were French and 1,868 Danes, but no register of Danish prisoners confined at Norman Cross has been found.

113

Mr. Share often heard his grandmother speak of her husband’s acts of kindness to the prisoners who were landed at Plymouth. One incident which he recollects was, that one day, just as the family were sitting down to dinner, Captain Holditch ran in, seized the large beefsteak pie just placed on the table, and carried it off, saying, “I want this, there are a batch of French prisoners going by, and they look famished, they must have it.”

Mr. Godwin (loc. cit.), mentioning that on Christmas Day 1805 some 250 French prisoners from Porchester Castle marched into Basingstoke on their cheerless way to Norman Cross (probably some of the heroes who had fought against Nelson and his captains on the 21st October), asks the question, “Did the Hampshire folk give them a share in their festivities?” The above anecdote justifies us, I hope, in saying that the answer to this question would be “Yes.”

114

These had been a considerable source of profit to the farmers, who had contracted to remove them regularly from their positions below the latrines, and had used their contents, with the rest of the refuse of the prison, as a guano to the great benefit of their land.

115

Histoire générale des traités de paix et autres transactions principales entre toutes les puissances de l’Europe depuis la paix de Westphalie. Ouvrage comprenant les travaux de Koch, Schoell, etc., entièrement refondus et continués jusqu’à ce jour. Paris 1848–87, 15 tom., vol. vi., p. 49.

116

His staff was as follows:

Wm. Gardiner, entered first clerk 1st September 1803 at £118 per annum, abate taxes 1s. in the pound, £9 6s., Civil List at 6d., leaving £8 19s. 8¾d. net per month.

Wm. Todd, 1st September, as store-clerk, at £118 per annum, and an extra £30 as French interpreter, with 18s. abatement; net per month £11 5s. 3½d.

John Andrew Delapoux, extra clerk, 1st September, at 3s. 6d. per diem. He was very uneasy about the proclamation against aliens, but was assured it would not apply to him.

Wm. Belcher, steward, at 3s. per day.

Thos. Adams, steward, 3rd September, at 3s. per day.

John Hobbs, turnkey, £50 per annum.

John Nolt, turnkey, £50 per annum.

John Belcher, turnkey, £50 per annum.

Alex Halliday, ditto, and as superintendent carpenter, £20, with 2s. 10½d. abatement for Civil List.

John Hayward, labourer, 12s. a week.

Wm. Powell, labourer, 12s. a week.

Captain Pressland was informed that no clothing of any kind was to be served out to any prisoner, though most were captured with none beyond what they stood upright in. No soup was to be served out, except to the prisoners who acted as barbers. He asked for some modification of this, but was refused. He was allowed £25 per annum for coals and candles, and 10s. 6d. each time he went to Peterborough on the Board’s Order or to make affidavits as to his accounts, etc. A few days afterwards this was increased to 12s. 6d. The military guard consisted of 400 of the North Lincoln Militia.

117

Chambers’ Journal of Literature, etc., loc. cit.

118

At this time Norman Cross and the other existing prisons were greatly overcrowded, but Wellington found it impossible to guard and maintain his prisoners on the Continent. Not only were the troops actually captured overwhelmingly numerous, but to their number were added deserters. In one of his dispatches, he writes: “Two battalions of the Regiment of Nassau, and one of Frankfort having quitted the enemies’ Army and passed over to that under my command. . . . I now send these troops to England.” The long-delayed completion of the prisons at Dartmoor and Perth would relieve the overcrowding of Norman Cross; but the resources of the staff must, in the meantime, have been strained to an extreme point to prevent the evils which might result from the state of matters. The breakdown of the various negotiations for exchange prevented the relief which was afforded during the first period of the war by the steady drain of prisoners sent back to their own country.

119

It is said that a memorandum exists in a private diary that the price paid for a picture of straw marquetry of Peterborough Cathedral was only £2; the picture must have taken weeks to construct.

120

The prison register confirms this paragraph. The last death certificate is that of Petronio Lambertini, a soldier of the Italian Regiment of the French Army. He died of consumption, and was presumably the last prisoner buried in the cemetery adjoining the North Road.

121

Loc. cit., p. 120.

122

The copy of the catalogue used by the auctioneer, with his note of the purchaser of and the price paid for each lot, is for the time in the writer’s hands, and has afforded much information, especially as to the construction of the buildings and the use to which each was appropriated.

Two years before this sale took place the Depot had been evacuated, and in the Public Record Office is the Barrack Master’s receipt to Captain Hanwell, dated 30th October 1814, for the Depot at Norman Cross, delivered over to him, agreeably to the Transport Board’s order of 24th September 1814. The document consists of ten pages in double columns.

123

Admiralty Records, Transport Department, Minutes No. 38; Records of Captains’ Services, O’ Byrne; Naval Biographical Dictionary; Naval Chronicle, vol. viii., 438; xiv., 283; xvi., 107, 108; xviii., 28; xix., 170–2; The Times, 26th February 1842.

124

M. Otto had at the date of this letter succeeded M. Niou as Commissary for the French Prisoners of War confined in Great Britain.

125

This was written three months before the fatal epidemic broke out in the prison.—T. J. W.

126

The number stated to be sick, on the 30th April 1810, includes convalescents, cases of wounds, accidents, etc.

127

Parliamentary Papers, 1810–11, vol. xi. (263), p. 115.

128

This is not a facsimile copy of the Register, which contains many abbreviations; it has been set out in columns, and abbreviated words have been written in full.