полная версия

полная версияPlain English

Exercise 4

All the words in italics are adjectives. Decide to which class each adjective belongs.

Note in this exercise the compound words used as adjectives, as: earth-born, self-made, new-lit, blood-rusted. Look up the meaning of these adjectives and see if you can use other adjectives in their places and keep the same meaning. Note the use of fellest.

Slavery, the earth-born Cyclops, fellest of the giant brood,Sons of brutish Force and Darkness, who have drenched the earth with blood,Famished in his self-made desert, blinded by our purer day,Gropes in yet unblasted regions for his miserable prey;—Shall we guide his gory fingers where our helpless children play?They have rights who dare maintain them; we are traitors to our sires,Smothering in their holy ashes Freedom's new-lit altar-fires;Shall we make their creed our jailer? Shall we, in our haste to slay,From the tombs of the old prophets steal the funeral lamps awayTo light up the martyr-fagots round the prophets of to-day?New occasions teach new duties; Time makes ancient good, uncouth;They must upward still, and onward, who would keep abreast of Truth;Lo, before us gleam her camp-fires! We ourselves must Pilgrims be,Launch our Mayflower, and steer boldly through the desperate winter sea,Nor attempt the Future's portal with the Past's blood-rusted key.—Lowell.Exercise 5

The following is from Oscar Wilde's story of The Young King. Oscar Wilde was a master of English, and if you have the opportunity, read all of this beautiful story and watch his use of adjectives. Mark the adjectives in this excerpt and use them in sentences of your own.

And as the young King slept he dreamed a dream, and this was his dream. He thought that he was standing in a long, low attic, amidst the whirr and clatter of many looms. The meager daylight peered in through the grated windows and showed him the gaunt figures of the weavers, bending over their cases. Pale, sickly-looking children were crouched on the huge crossbeams. As the shuttles dashed through the warp they lifted up the heavy battens, and when the shuttles stopped they let the battens fall and pressed the threads together. Their faces were pinched with famine, and their thin hands shook and trembled. Some haggard women were seated at a table, sewing. A horrible odor filled the place. The air was foul and heavy, and the walls dripped and streamed with damp.

The young King went over to one of the weavers and stood by him and watched him.

And the weaver looked at him angrily and said, "Why art thou watching me? Art thou a spy set on us by our master?"

"Who is thy master?" asked the young King.

"Our master!" cried the weaver, bitterly. "He is a man like myself. Indeed, there is but this difference between us—that he wears fine clothes while I go in rags, and that while I am weak from hunger he suffers not a little from overfeeding."

"The land is free," said the young King, "and thou art no man's slave."

"In war," answered the weaver, "the strong make slaves of the weak, and in peace the rich make slaves of the poor. We must work to live, and they give us such mean wages that we die. We toil for them all day long, and they heap up gold in their coffers, and our children fade away before their time, and the faces of those we love become hard and evil. We tread out the grapes, another drinks the wine. We sow the corn, and our own board is empty. We have chains, though no eye beholds them; and are slaves, though men call us free."

"Is it so with all?" he asked.

"It is so with all," answered the weaver, "with the young as well as with the old, with the women as well as with the men, with the little children as well as with those who are stricken in years. The merchants grind us down, and we must needs do their bidding. The priest rides by and tells his beads, and no man has care of us. Through our sunless lanes creeps Poverty with her hungry eyes, and Sin with his sodden face follows close behind her. Misery wakes us in the morning, and Shame sits with us at night. But what are these things to thee? Thou art not one of us. Thy face is too happy." And he turned away scowling, and threw the shuttle across the loom, and the young King saw that it was threaded with a thread of gold.

And a great terror seized upon him, and he said to the weaver, "What robe is this that thou art weaving?"

"It is the robe for the coronation of the young King," he answered; "What is that to thee?"

And the young King gave a loud cry and woke and lo! he was in his own chamber, and through the window he saw the great honey-colored moon hanging in the dusky air.

SPELLING

LESSON 14

You remember in the formation of plurals, we learned that words ending in y change y to i when es is added; as, lady, ladies; baby, babies; dry, dries, etc.

There are several rules concerning words ending in y, knowledge of which will aid us greatly in spelling.

1. Words ending in ie change the ie to y before ing to prevent a confusing number of vowels. For example, die, dying; lie, lying; tie, tying.

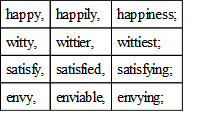

2. Words of more than one syllable ending in y preceded by a consonant, change y into i before all suffixes except those beginning with i. For example:

This exception is made for suffixes beginning with i, the most common of which is ing, to avoid having a confusing number of i's.

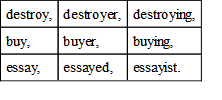

3. Most words ending in y preceded by a vowel retain the y before a suffix. For example:

The following words are exception to this rule:

laid,

paid,

said,

daily,

staid.

Make as many words as you can out of the words given in this week's spelling lesson by adding one or more of the following suffixes: er, est, ed, es, ing, ly, ness, ful, ment, al.

Monday

Beauty

Portray

Deny

Rare

Multiply

Tuesday

Mercy

Bury

Obey

Lovely

Envy

Wednesday

Tie

Defy

Study

Decry

Crazy

Thursday

Merry

Silly

Lusty

Imply

Day

Friday

Dismay

Duty

Employ

Satisfy

Pretty

Saturday

Pay

Joy

Journey

Qualify

Sorry

PLAIN ENGLISH

LESSON 15

Dear Comrade:

In this week's lesson we are finishing the study of adjectives, which adds another part of speech to those which we have studied. We can see in the study of each additional part of speech how each part has its place in the expression of our ideas. We could not express ourselves fully if we lacked any of these parts of speech. Each one is not an arbitrary addition to our language but has come to us out of the need for it. We see that there are no arbitrary rules but in language, as in all things else, growing needs have developed more efficient tools. With these have grown up certain rules of action so we can have a common usage and system in our use of these tools. It has taken years of effort to accomplish this. The changes have been slow and gradual, and this language which we are studying is the finished product.

This slow development in the use of language, even in our own lives, makes us realize how many thousands of years it must have taken our primitive ancestors to reach a point where they could use the phonetic alphabet. We have found that at first they used simple aids to memory, as knotted strings and tally sticks. Then they began to draw pictures of things about them and so were able to communicate with one another by means of these pictures. When a man was going away from his cave and wanted to leave word for those who might come, telling them where he had gone and how soon he would return, he drew a picture of a man over the entrance with the arm extended in the direction in which he had gone. Then he drew another picture of a man in a sleeping position and also one of a man with both hands extended in the gesture which indicated many. These two pictures showed that he would be away over many nights. In some such rude manner as this, they were able to communicate with one another.

But man soon began to think, and he needed to express ideas concerning things of which he could not draw pictures. He could draw a picture of the sun, but how could he indicate light? How could he indicate the different professions in which men engaged, such as the farmer and priest, etc.?

He was forced to invent symbols or signs to express these ideas, so his writing was no longer a picture of some object, but he added to it symbols of abstract ideas. A circle which stood for the sun written with the crescent which stood for the moon, indicated light. The bee became a symbol of industry. An ostrich feather was a symbol of justice, because these feathers were supposed to be of equal length. A picture of a woman stood simply for a woman, but a picture of two women stood for strife, and three women stood for intrigue. These old ancestors of ours became wise quite early concerning some things. The symbol for a priest in the early Egyptian picture writing was a jackal. Perhaps not because he "devoured widows' houses," but because the jackal was a very watchful animal. The symbol for mother was a vulture because that bird was believed to nourish its young with its own blood.

It naturally required a good memory and a clear grasp of association to be able to read this sort of writing. It required many centuries for this slow development of written speech.

The development of language has been a marvelous growth and a wonderful heritage has come to us. Let us never be satisfied until we have a mastery of our language and find a way to express the ideas that surge within us. A mastery of these lessons will help us.

Yours for Education,THE PEOPLE'S COLLEGE.ADJECTIVES AND PRONOUNS

258. From our study of the adjective, we know that it is a word used with a noun to qualify or limit its meaning. But a great many times we find these adjectives used without the noun which they modify. As, for example, I may say, This is mine, and the adjective this is used alone without the noun which it modifies, and you are able to tell only by what I have been saying or by some action of mine to what I am referring when I say this.

When adjectives are used in this manner, they are used like pronouns—in place of a noun. So sometimes we find an adjective used with a noun, and sometimes used as a pronoun, in place of a noun; and since we name our parts of speech by the work which they do in the sentence, an adjective used in this way is not an adjective, but a pronoun or word used in place of a noun.

So these words are pronouns when they stand alone to represent things—when they are used in place of a noun. They are adjectives when they are used with a noun to limit or qualify the noun. For example, I may say, This tree is an elm, but that tree is an oak. This and that in this sentence are adjectives used to modify the noun tree. But I may say, This is an oak and that is an elm, and in this sentence this and that are used without a noun, they are used as pronouns.

259. Our being able to name every part of speech is not nearly so important as our being able to understand the functions of the different parts of speech and being able to use them correctly. But still it is well for us to be able to take a sentence and point out its different parts and tell what each part is and the function which it serves in the sentence. So sometimes in doing this we may find it difficult to tell whether certain words are adjectives or pronouns. We can distinguish between adjectives and pronouns by this rule:

When you cannot supply the noun which the adjective modifies, from the same sentence, then the word which takes the place of the noun is a pronoun, but if you can supply the omitted noun from the same sentence, then the word is used as an adjective. Thus, we do not say that the noun is understood unless it has already been used in the same sentence and is omitted to avoid repetition. We make each sentence a law unto itself and classify each word in the sentence according to what it does in its own sentence.

So if a noun does not occur in the same sentence with the word about which we are in doubt as to whether it is a pronoun or adjective, it is a pronoun or word used in place of a noun. For example, in the sentence, This book is good but that is better; book is understood after the word that and left out to avoid tiresome repetition of the word book. Therefore that is an adjective in this sentence. But if I say, This is good, but that is better; there is no noun understood, for there is no noun in the sentence which we can supply with this and that. Therefore in this sentence this and that are pronouns, used in place of the noun. And since this and that, when used as adjectives, are called demonstrative adjectives; therefore when this and that, these and those, and similar words, are used as pronouns they are called demonstrative pronouns.

260. Be careful not to confuse the possessive pronouns with adjectives. Possessive pronouns modify the nouns with which they are used, but they are not adjectives, they are possessive pronouns. My, his, her, its, our, your and their are all possessive pronouns, not adjectives. Also be careful not to confuse nouns in the possessive form with adjectives.

ADJECTIVES AS NOUNS

261. Sometimes you will find words, which we are accustomed to look upon as adjectives, used alone in the sentence without a noun which they modify. For example, we say, The strong enslave the weak. Here we have used the adjectives strong and weak without any accompanying noun. In sentences like this, these adjectives, being used as nouns, are classed as nouns. Remember, in your analysis of a sentence, that you name every word according to the work which it does in that sentence, so while these adjectives are doing the work of nouns, we will consider them as nouns.

These words are not used in the same manner in which demonstrative adjectives are used as pronouns. There is no noun omitted which might be inserted, but these adjectives are used rather to name a class. As, for example; when we say, The strong, The weak, we mean all those who are strong and all those who are weak, considered as a class. You will find adjectives used in this way quite often in your reading, and you will find that you use this construction very often in your ordinary speech. As, for example:

The rich look down upon the poor.

The wise instruct the ignorant.

Many examples will occur to you. Remember these adjectives are nouns when they do the work of nouns.

ADJECTIVES WITH PRONOUNS

262. Since pronouns are used in place of nouns, they may have modifiers, also, just as nouns do. So you will often find adjectives used to modify pronouns. As, for example; He, tired, weak and ill, was unable to hold his position. Here, tired, weak and ill are adjectives modifying the pronoun he.

263. We often find a participle used as an adjective with a pronoun. As, for example:

She, having finished her work, went home.

They, having completed the organization, left the city.

He, having been defeated, became discouraged.

In these sentences, the participles, having finished, having completed, and having been defeated, are used as adjectives to modify the pronouns she, they and he.

COMPARISON

264. We have found that adjectives are a very important part of our speech for without them we could not describe the various objects about us and make known to others our ideas concerning their various qualities. But with the addition of these helpful words we can describe very fully the qualities of the things with which we come into contact. We soon find, however, that there are varying degrees of these qualities. Some objects possess them in slight degree, some more fully and some in the highest degree. So we must have some way of expressing these varying degrees in the use of our adjectives.

This brings us to the study of comparison of adjectives. Suppose I say:

That orange is sweet, the one yonder is sweeter, but this one is sweetest.

I have used the adjective sweet expressing a quality possessed by oranges in three different forms, sweet, sweeter and sweetest. This is the change in the form of adjectives to show different degrees of quality. This change is called comparison, because we use it when we compare one thing with another in respect to some quality which they possess, but possess in different degrees.

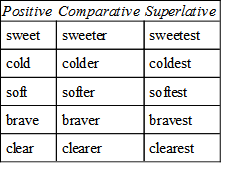

The form of the adjective which expresses a simple quality, as sweet, is called the positive degree. That which expresses a quality in a greater degree, as sweeter, is called the comparative degree. That which expresses a quality in the greatest degree, as sweetest, is called the superlative degree.

265. Comparison is the change of form of an adjective to denote different degrees of quality.

There are three degrees of comparison, positive, comparative and superlative.

The positive degree of an adjective denotes simple quality.

The comparative degree denotes a higher degree of a quality.

The superlative degree denotes the highest degree of a quality.

266. Most adjectives of one syllable and many adjectives of two syllables regularly add er to the positive to form the comparative degree, and est to the positive to form the superlative degree, as:

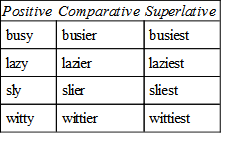

267. Adjectives ending in y change y to i and add er and est to form the comparative and superlative degree, as:

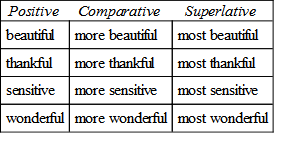

268. Many adjectives cannot be compared by this change in the word itself, since the addition of er and est would make awkward or ill-sounding words. Hence we must employ another method to form the comparison of this sort of words. To say, beautiful, beautifuller, beautifullest, is awkward and does not sound well. So we say beautiful, more beautiful, most beautiful.

Many adjectives form the comparative and superlative degree by using more and most with the simple form of the adjective, as:

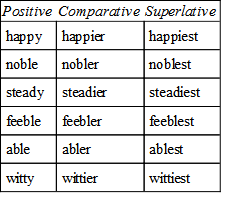

269. Adjectives of two syllables, to which er and est are added to form the comparison, are chiefly those ending in y or le, such as:

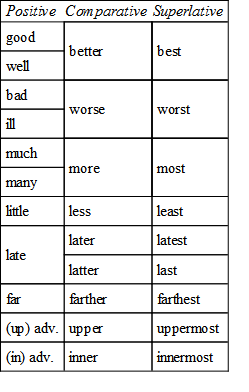

270. Some adjectives, few in number, but which we use very often, are irregular in their comparison. The most important of these are as follows: (It would be well to memorize these.)

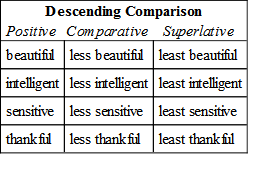

DESCENDING COMPARISON

271. The change in form of adjectives in the positive, comparative and superlative shows that one object has more of a quality than others with which it is compared. But we also wish at times to express the fact that one object has less of the quality than is possessed by others with which it is compared; so we have what we may call the descending comparison, by means of phrases formed by using less and least instead of more and most. Using less with the positive degree means a degree less than the positive, while using least expresses the lowest degree. For example:

PARTICIPLES AS ADJECTIVES

272. You remember, when we studied the participle, that we found it was called a participle because it partook of the nature of two or more parts of speech. For example; in the sentence, The singing of the birds greeted us; singing is a participle derived from the verb sing, and is used as a noun, the subject of the verb greeted.

But participles are used not only as nouns; they may also be used as adjectives. For example; we may say, The singing birds greeted us. Here the participle singing describes the birds, telling what kind of birds greeted us, and is used as an adjective modifying the noun birds.

You will recall that we found there were two forms of the participle, the present participle and the past participle. The present participle is formed by adding ing to the root form of the verb; and the past participle in regular verbs is formed by adding d or ed to the root form, and in irregular verbs by a change in the verb form itself. These two simple forms of participles are often used as adjectives.

273. The present participle is almost always active; that is, it refers to the actor. As, for example; Vessels, carrying soldiers, are constantly arriving. Here the present participle carrying describes the noun vessels, and yet retains its function as a verb and has an object, soldiers. So it partakes of two parts of speech, the verb and the adjective.

274. The past participle, when used alone, is almost always passive, for it refers not to the actor, but to what is acted upon, thus:

The army, beaten but not conquered, prepared for a siege.

In this sentence beaten is the past participle of the irregular verb beat, and conquered is the past participle of the regular verb conquer, and both modify the noun army, but refer to it, not as the actor, but as the receiver of the action. Hence, the past participle is also the passive participle.

Note in the following sentences the use of the present and past participle as adjectives:

A refreshing breeze came from the hills.

They escaped from the burning building.

Toiling, rejoicing, sorrowing, onward through life he goes.

The man, defeated in his purpose, gave up in despair.

The child, driven in its youth to work, is robbed of the joy of childhood.