полная версия

полная версияThe 56th Division

On the left the position was as uncertain as it had been the previous day on the right. The 14th Division claimed to be in the Wancourt Line, and eventually it was found that they had swerved to their left and created a large gap between their right and the left of the London Scottish, who were lying out in the open.

So the situation (B) remained through the night. The next day, the 11th, nothing was done on the left of the line, but the 167th Brigade carried on their good work and the Queen Victoria’s Rifles cleared the Hindenburg Line as far as the Cojeul River, and a long length of Nepal Trench, which was part of the Wancourt Line. The difficulty of the 30th Division was apparently uncut wire. They seemed to be stuck facing the Hindenburg Line, while the Queen Victoria’s Rifles cleared it. A Corps telegram to this division reads:

“Not satisfied that the infantry are receiving sufficient support from the artillery. The situation demands that as many batteries as possible be pushed forward so that enemy machine guns be dealt with at decisive range.”

The 167th were relieved by the 169th Brigade late in the afternoon, after three days of very severe and successful fighting.

The 169th Brigade were ordered to consolidate Hill 90 and to push patrols into Heninel, and later, when the 30th Division had occupied the Hindenburg Line, to cross the River Cojeul and make good the high ground to the south.

The attack ordered started at 5.15 a.m. on the 12th, and after stiff bombing fights, the 2nd and 5th London Regts., working to the north and south of Hill 90, joined hands on the other side of it. It was found necessary, during this operation, to have a password, so that converging parties should not bomb each other. To the great amusement of the men the words “Rum jar” were chosen. The Germans, being bombed from both sides, must have thought it an odd slogan. The enemy were then seen withdrawing from Heninel, and the leading company of the 2nd London Regt. immediately advanced and occupied the village. The 30th Division then crossed to the south of the Cojeul River, and made progress along the Hindenburg Line. Meanwhile the 2nd London Regt. had pushed forward patrols and occupied the high ground to the east of Heninel, where they got in touch with the 30th Division.

The occupation of Hill 90, which had been made possible by the 167th Brigade and the Queen Victoria’s Rifles (attached), also caused the enemy to vacate the village of Wancourt, which was entered by patrols of the London Rifle Brigade about eleven o’clock. The 14th Division moved two battalions, one on either side of the village, with a view to continuing the advance to the high ground east of the Cojeul River, and at 1 p.m. the Corps ordered the advance to be continued to the Sensée River; but these orders were modified and the 56th Division was told to consolidate (C) and prepare for an advance on the 13th.

On the 13th April nothing much was done. The 56th Division held the ridge from 35 to Wancourt Tower; on the right the 33rd Division, which had relieved the 30th, failed to advance; on the left the 50th Division, which had relieved the 14th on the preceding night, also failed to advance, having been held up by machine-gun fire from Guemappe. But the Corps ordered a general advance on the next day, the objective being the line of the Sensée River.

During the night the enemy blew up Wancourt Tower, which seemed to suggest that he was contemplating retirement. At 5.30 a.m. our attack was launched, but almost at once the 169th Brigade reported that the Queen’s Westminster Rifles had gone forward with no one on their left. About five hundred yards in front of them were some practice trenches which the enemy had used for bombing. Capt. Newnham writes of the attack dissolving about the line of these trenches. Apparently Guemappe had not been taken on the left, and a perfect hail of machine-gun fire enfiladed the advancing troops from this village. The Queen Victoria’s Rifles, who attacked on the right, met with no better fate, the leading waves being wiped out. From the diary of 169th Brigade we learn that

“the 151st Brigade attack on our left never developed, leaving our flank exposed. Enemy met with in considerable strength; they had just brought up fresh troops, and the allotment of machine guns, according to prisoners, was two per battalion. The 151st Brigade attack was ordered with their left flank on Wancourt Tower, which was our left and the dividing-line between brigades. Great confusion consequently on our left front, where two battalions of Durhams were mixed up with the Queen’s Westminster Rifles, and the London Rifle Brigade, moving up in support, added to the congestion. Casualties were heavy—Queen’s Westminster Rifles, 12 officers, 300 other ranks; Queen Victoria’s Rifles, 15 officers and 400 other ranks.”

The attack had not, however, dissolved at all points, as a thin line of troops undoubtedly advanced a thousand yards, and more, beyond the practice trenches. But these gallant fellows soon found themselves in a very lonely position, and as the 30th and 50th Divisions failed to make any ground at all, they had Germans practically on all sides of them. They remained for some time and eventually withdrew.

The next two days, the 15th and 16th, were occupied in consolidating the ground gained. The division had alarms of counter-attack, but nothing developed on their front. On the left, however, the enemy attacked and recaptured Wancourt Tower from the 50th Division. This point was not retaken by us until the next day, but the 56th Division were not concerned. Further advance was postponed until the 22nd April, and on the 18th the 30th Division took over the line from the 56th Division.

This was the opening battle of the Arras series, and is known as the First Battle of the Scarpe, 1917, and is linked up with the Battle of Vimy Ridge. The student would do well to consider the two battles as one. The capture of Vimy Ridge by the Canadians, and of Monchy by troops of the Third Army, gave us positions of great importance and improved the situation round Arras. The feeling of the 56th Division was that it had been a great fight, and that they had proved themselves undoubtedly better men than the Germans. The capture of Neuville Vitasse and subsequent rolling up of the Hindenburg Line to the south of Heninel was a feat of which they felt proud. And they had killed a lot of the enemy at close quarters.

It is an interesting battle, as it undoubtedly inflicted a terrifying defeat on the enemy. Ludendorff says of it4:

“The 10th April and the following days were critical. The consequences of a break through, of 12 to 15 kilometres wide and 6 or more kilometres deep, are not easy to meet. In view of the heavy losses in men, guns, and ammunition resulting from such a break through, colossal efforts are needed to make good the damage.... A day like 9th April threw all calculations to the winds. Many days had to pass before a line could really be formed and consolidated. The end of the crisis, even if troops were available, depended very largely, as it generally does in such cases, on whether the enemy, after his first victory, would attack again, and by further success aggravate the difficulty of forming a new line. Our position having been weakened, such victories were to be won only too easily....”

Hindenburg also confesses to very anxious moments, and suggests that “the English did not seem to have known how to exploit the success they had gained to the full.”

In his dispatch on this battle Sir Douglas Haig said that:

“With the forces at my disposal, even combined with what the French proposed to undertake in co-operation, I did not consider that any great strategical results were likely to be gained by following up a success on the front about Arras, and to the south of it, beyond the capture of the objectives aimed at.... It was therefore my intention to transfer my main offensive to another part of the front after these objectives had been secured.

The front selected for these operations was in Flanders. They were to be commenced as soon as possible after the Arras offensive, and continued throughout the summer, so far as the forces at my disposal would permit.”

It must be remembered that the plans for the year were drawn up in consultation with our Allies, and the battles of Arras must be taken as a part only of those plans. The First and Third Armies secured positions which Sir Douglas Haig intended that they should secure; they inflicted great loss on the enemy, more than 13,000 prisoners and over 200 guns; they drew German reserves until at the end of the operations there were twice as many enemy troops on that front as at the beginning, which materially helped our Allies, who were on the point of launching a big offensive on the Aisne and in Champagne. On the whole, these battles fulfilled their object and may be viewed with satisfaction.

On the 16th April the French attacked the Chemin-des-Dames, north-west of Rheims, and in the Champagne, south of Rheims. They met with very heavy losses and most obstinate resistance. These were the much-discussed operations under Gen. Nivelle, and, in order to assist, Sir Douglas Haig agreed to continue the operations round Arras longer than was his first intention. Plans, which had been made for a rearrangement of artillery and troops for the operations at Ypres, were cancelled, and orders were issued for a continuance, with shallow objectives, of the fighting at Arras.

The First Battle of the Scarpe and the Battle of Vimy Ridge were, therefore, the original scheme, and the subsequent battles should be considered with this fact in mind. They were: the Second Battle of the Scarpe, 1917, 23rd-24th April; the Battle of Arleux, 28th-29th April; the Third Battle of the Scarpe, 1917, 3rd-4th May. The Battle of Bullecourt, 3rd-17th May, and a number of actions must also be included in the subsequent Arras offensive.

A few days’ rest was granted to the 56th Division. The 167th Brigade was round Pommier, the 168th round Couin, the 169th round Souastre. Divisional Headquarters were first at Couin and then at Hauteville. On the 25th Gen. Hull was ordered to hold himself in readiness to move into either the VI or the VII Corps, and the next day was definitely ordered into the VI Corps. On the 27th the 167th Brigade relieved the 15th Division in the front line, and Divisional Headquarters opened in Rue de la Paix, Arras.

* * * * * * *From the Harp, which it will be remembered was the original line, to east of Monchy there runs a ridge of an average height of 100 metres; at Monchy itself it rises above 110 metres. This ridge shoots out a number of spurs towards the Cojeul River to the south. The position taken over by the 167th Brigade was from a small copse south-east of Monchy to the Arras-Cambrai road, about 500 yards from the Cojeul, and on the reverse slope of one of these spurs. Observation for them was bad, and the enemy trenches were well sited and frequently over the crest of the hill.

On the 29th the 169th Brigade took over the right of the line from the 167th. The front line was then held by the London Rifle Brigade, the 2nd London Regt., the 1st London Regt., and the 7th Middlesex Regiment. The Queen Victoria’s Rifles were in support of the Queen’s Westminster Rifles in reserve to the right brigade, and the 3rd London Regt. in support and the 8th Middlesex Regt. in reserve to the left brigade.

With a view to the important operations which the French were to carry out on the 5th May, it was decided to attack on an extended front at Arras on the 3rd. While the Third and First Armies attacked from Fontaine-les-Croisilles to Fresnoy, the Fifth Army launched an attack on the Hindenburg Line about Bullecourt. This gave a total front of over sixteen miles. [The Third Battle of the Scarpe, 1917.]

Zero hour was 3.45 a.m., and in the darkness, illumined by wavering star-shells fired by a startled enemy, and with the crashing of the barrage, the men of the 56th Division advanced from their assembly trenches. As soon as the first waves topped the crest, they were met with a withering machine-gun and rifle fire. The ground was confusing and the darkness intense—officers, as was so often the case in night attacks, found it impossible to direct their men. Exactly what happened will never be known in detail. No reports came in for a considerable time.

With daylight the artillery observation officers began to communicate with headquarters. Our men, they said, had advanced 1,000 yards on the right, and were digging in near a factory (Rohart) on the bank of the Cojeul, and the 14th Division on their right seemed to have reached its objectives. About 300 yards over the crest of the spur was a trench known as Tool, and this seemed to be occupied by the enemy.

Soon after this the 169th Brigade reported that the London Rifle Brigade were holding a pit near the factory and a trench about the same place; the 2nd London Regt. had a footing in Tool Trench. The latter position is doubtful, but the 2nd Londons were well forward.

Cavalry Farm, near and to the right of the original line, was still held by the enemy, and about 10 o’clock the Queen Victoria’s Rifles, after a short bombardment by the Stokes mortars, rushed and secured the farm. They found a number of dugouts, which they bombed, and secured 22 prisoners. The farm was connected with Tool Trench, and they proceeded to bomb their way up it. It would appear, therefore, that the 2nd London Regt. held a small section of this trench farther to the north, if any at all.

We must now follow the 167th Brigade on the left. The two attacking battalions had been met with even worse machine-gun fire than the 169th Brigade. There was no news of them for a long time. It is clear that neither the 1st London Regt. nor the 7th Middlesex ever held any of Tool Trench, but a few gallant parties did undoubtedly overrun Tool, and, crossing a sunken road known as Stirrup Lane, reached Lanyard Trench, quite a short distance from the men of the London Rifle Brigade, who had lodged themselves in the pit near Rohart Factory. They were, however, not in sufficient numbers to join hands with the London Rifle Brigade, or some small groups of the 2nd London, who were also in advanced shell-holes, and about 8 o’clock in the evening were forced to surrender. (A small party was seen marching east without arms.) The remaining 1st London and 7th Middlesex men lay out in shell-holes in front of Tool Trench.

Soon after the Queen Victoria’s Rifles had captured Cavalry Farm and started to bomb up Tool Trench, with the forward artillery and trench mortars helping them, the 3rd Division on the left of the 56th declared that their men were in the northern end of Tool. They asked that the artillery should be lifted off the trench, as they were going to bomb down towards the Queen Victoria’s Rifles. But it appears that they were very soon driven out, as by 3 p.m. the 3rd Division were definitely reported to be in touch with the 7th Middlesex in the original line.

Meanwhile the 14th Division, on the right, which had made good progress at the start, had been violently counter-attacked, and at 11.50 a.m. reported that they had been driven back to their original line.

Brig.-Gen. Coke, of the 169th Brigade, now found his men in a queer position. The troops on either flank of his brigade were back in the line they had started from; he ascertained that none of his brigade were north of the Arras-Cambrai road, and so he held a long tongue in the valley of the Cojeul open to attack from the high ground on either side of it.

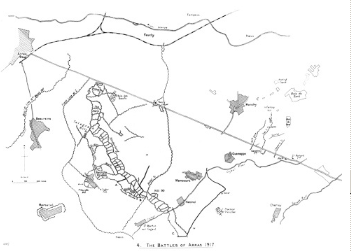

4. The Battles of Arras 1917.

Much movement by the enemy was observed during the afternoon; reinforcements were assembling in Tool and the sunken road behind it. About 10 o’clock in the evening the Germans started a fierce bombardment of the tongue of land held by the London Rifle Brigades and 2nd London Regts., and, after an hour of ceaseless fire, counter-attacked and drove the troops back to their original lines.

Gen. Hull then ordered them to hold their original line and reorganise, but before the orders could reach them these two fine battalions had attacked again and reoccupied all the positions they had gained in the morning with the exception of Cavalry Farm. But they were in a bad situation. With the enemy holding the Cambrai road in force, the only communication with the advanced troops was down the bottom of the valley, a place of much water and mud. Brig.-Gen. Coke therefore withdrew his men just before sunrise. They brought with them, however, a German officer and 15 men who had surrendered in the neighbourhood of Cavalry Farm.

It had been a day of very hard fighting, and the gain on the whole of the sixteen miles of front attacked was Fresnoy, which had been taken by the Canadians, and a portion of the Hindenburg Line, east of Bullecourt, captured by the Australians. The enemy had been terribly frightened by the successful start of the battles of Arras. Hindenburg and Ludendorff were putting into effect their new system of holding the front in depth, but thin in the forward zones, with many machine guns, and strong supports for immediate counter-attack. It seemed as though their system had broken down at the first test, and, as the Russians were no longer a menace to them, they poured reinforcements across Germany. But, as we know, this continuation of the offensive was with the object of helping our Allies by holding troops and guns which might otherwise have been used against them.

The 167th and 169th Brigades held the line for one day more, and were relieved by the 168th on the 5th May. The latter brigade also took over a stretch of extra line to the north.

The enemy was exceedingly quiet and our patrols very active. If any indication is wanted of the high moral of the 56th Division, it can be found in this patrol work. After an action of this kind, when the two brigades lost just on a thousand men, really audacious reconnoitring deserves the highest praise. Again and again attempts were made by patrols to enter Tool Trench, only to find the enemy alert. Cavalry Farm, on the right, and the copse, on the left, were both entered and found unoccupied; but the exact position of the enemy in Tool Trench was ascertained.

Meanwhile the heavy artillery kept up a steady fire on Tool Trench, causing large numbers of Germans to run over the open and seek safer ground. And troops worked hard on our trenches, which were greatly improved.

At 8.30 p.m. on the 11th May the 4th London Regt. on the right and the London Scottish on the left attacked Cavalry Farm and the trench on the far side of it, and Tool Trench.

A practice barrage on the previous day had drawn heavy fire in a few minutes, and it had been decided not to have a barrage, but to keep the heavy artillery firing steadily to the last minute. The enemy, who held the line in full strength, were taken by surprise. Only Cavalry Farm was visible from our line, and the 4th London Regt. swept into this place with no difficulty. But the right of the enemy line was able to put up a fight, and the left company of the London Scottish suffered somewhat severely. Except for this one point, the trench was vacated by its garrison in a wild scramble. They could not, however, escape the Lewis gunners and brigade machine-gunners, who did some good execution. Quite a lot of the enemy were killed in the trench and a round dozen taken prisoner—they were of the 128th Infantry Regt. and the 5th Grenadier Regt. Eight machine guns were also found.

Tool Trench was only a part of the enemy line which ran up the hill on the east of Monchy. To the south of the copse it was Tool and to the north it was Hook. The very northern end of Tool and all of Hook remained in the hands of the enemy. A block was made by filling in about forty yards of the trench and the new line was consolidated.

The new line had been much damaged by our fire, but it was soon reconstructed, and two communication trenches were dug to the old line. Meanwhile the trench mortars kept up a steady bombardment of Hook Trench, and snipers picked off the enemy as he attempted to seek the safer shell-holes in the open.

During the next few days several deserters from the 5th Grenadier Regt. came in, and they, in common with other prisoners, persisted in stating that the enemy was contemplating a retirement. Patrols, however, always found Lanyard Trench and Hook fully garrisoned. The 167th Brigade had taken over the line from the 168th, and the 8th Middlesex attempted to rush both Lanyard and Hook; this was not done in force, but was more in the nature of a surprise by strong patrols. They found the enemy too alert.

On the 19th something in the nature of an attack in force was carried out. The 8th Middlesex made a night attack, in conjunction with the 29th Division, on Hook Trench and the support line behind it. The Middlesex men gained the junction of Hook and Tool, but were very “bunched”; the 187th Brigade on the left made no progress at all. It is probable that the Middlesex were more to the left than they imagined, as they were heavily bombed from both flanks, and eventually forced to withdraw.

On the 20th May the weary troops of the 56th Division were relieved by the 37th Division.

In these actions and in the battle on the 3rd May the objectives were shallow and the enemy fully prepared to resist, with large reinforcements of men and guns in the field. The enemy barrage was considered the heaviest that had, as yet, been encountered. The positions attacked were well sited and frequently masked, and there was also the complication of night assaults at short notice. Brig.-Gen. Freeth, in an interesting report of the battle on the 3rd, says:

“… Owing to the darkness it was extremely difficult for the assaulting troops to keep direction or the correct distances between waves. The tendency was for rear waves to push forward too fast for fear of losing touch with the wave in front of them. Consequently, by the time the leading wave was approaching Tool Trench, all the rear waves had telescoped into it. Even if Tool Trench had been taken, much delay would have been caused in extricating and moving forward waves allotted to the further objectives.”

Anyone who has taken part in a night attack will appreciate these difficulties. If it goes well it is very well, but if not the confusion is appalling.

The casualties from the 29th April to 21st May were 79 officers and 2,022 other ranks.

The general situation was that on the 5th May the French had delivered their attack on the Chemin-des-Dames and achieved their object, but on the whole the French offensive was disappointing. On the British front, however, 19,500 prisoners and 257 guns had been captured, and the situation round Arras greatly improved. The spring offensive was at an end.

But fighting did not cease round Arras and over the width of the sixty square miles of regained country. The Messines attack in the north was in course of preparation, and the orders to the Fifth, Third, and First Armies were to continue operations, with the forces left to them, with the object of keeping the enemy in doubt as to whether the offensive would be continued. Objectives, of a limited nature, were to be selected, and importance given to such actions by combining with them feint attacks. They were successful in their object, but there was bitter with the sweet, as Sir Douglas Haig writes:

“These measures seem to have had considerable success, if any weight may be attached to the enemy’s reports concerning them. They involved, however, the disadvantage that I frequently found myself unable to deny the German accounts of the bloody repulse of extensive British attacks which, in fact, never took place.”

The attack on Messines was launched on the 7th June, and was a complete success. With the first crash of our concentrated artillery nineteen mines were exploded, and our troops swept forward all along the line. By the evening 7,200 prisoners, 67 guns, 94 trench mortars, and 294 machine-guns had been captured.

The 56th Division indulged in a little well-earned rest. We read of sports and horse shows in the vicinity of Habarcq, of concerts given by the “Bow Bells” concert party (formed in 1916 at Souastre), and diaries have the welcome entries “troops resting” as the only event of the day. But this was not for long. Battalions were soon back in the line, though much reduced in strength. For the first time we find, in spite of reinforcements, that the average strength of battalions fell to just over eight hundred.