полная версия

полная версияThe Eighteen Christian Centuries

But a firmer barrier against the encroachments of kings and nobles than the written words of Magna Charta was still required, and people were not long in seeing how little to be trusted are legal forms when the contracting parties are disposed to evade their obligations. John indeed attempted, in the very year that saw his signature to the Charter, to expunge his name from the obligatory deed by the plenary power of the Pope. Innocent had no scruple in giving permission to his English vassal to break the oath and swerve from his engagement. But the English spirit was not so broken as the king’s, and the barons took the management of the country into their own hands. When the experience of a few years of Henry the Third had shown them that there was no improvement on the personal character of his predecessor, they took effectual measures for the protection of all classes of the people. Henry began his inglorious reign in 1216, and ended it in 1272. In those fifty-six years great changes took place, but all in an upward direction, out of the darkness and unimpressionable stolidity of previous ages. The dawn of a more intellectual period seemed at hand, and already the ghosts of ignorance and oppression began to scent the morning air. In 1264 an example was set by England which it would have been well if all the other Western lands had followed, for by the institution of a true House of Commons it laid the foundation for the only possible liberal and improvable government,—the only government which can derive its strength from the consent of the governed legitimately expressed, and vary in its action and spirit with the changes in the general mind. In cases of error or temporary delusion, there is always left the most admirable machinery for retracing its steps and rectifying what is wrong. In cases of universal approval and unanimous exertion, there is no power, however skilfully wielded by autocrats or despots, which can compare with the combined energy of a whole and undivided people.

|A.D. 1226-1270.|

The contemporary of this Henry on the throne of France was the gentle and honest Louis the Ninth. If those epithets do not sound so high as the usual phraseology applied to kings, we are to consider how rare are the examples either of honesty or gentleness among the rulers of that time, and how difficult it was to possess or exercise those virtues. But this gentle and honest king, who was scarcely raised in rank when the Church had canonized him as a saint, achieved as great successes by the mere strength of his character as other monarchs had done by fire and sword. His love of justice enabled him to extend the royal power over his contending vassals, who chose him as umpire of their quarrels and continued to submit to him as their chief. He heard the complaints of the lower orders of his people in person, sitting, like the kings of the East, under the shade of a tree, and delivering judgment solely on the merits of the case. His undoubted zeal on behalf of his religion permitted him, without the accusation of heresy, to put boundaries to the aggressions of the Church. He resisted its more violent claims, and gave liberty to ecclesiastics as well as laymen, who were equally interested in the curtailment of the Papal power. He granted a great number of municipal charters, and published certain Establishments, as they were called, which were improvements on the old customs of the realm and were in a great measure founded on the Roman law. The spirit of the time was popular progress; and both in France and England great advances were made; deliberative national assemblies took their rise,—in France, under the conscientious monarch, with the full aid and influence of the royal authority, in England, under the feeble and selfish Henry, by the necessity of gaining the aid of the Commons against the Crown to the outraged and insulted nobility. In both nations these assemblies bore for a long time very distinguishable marks of their origin. The Parliaments of France, sprung from the royal will, were little else than the recorders of the decrees of the monarch; while the Parliaments of England, remembering their popular origin, have always had a feeling of independence, and a tendency to make rather hard bargains with our kings. Even before this time the Great Council had occasionally opposed the exactions of the Crown; but when the falsehood and avarice of Henry III. had excited the popular odium, the barons of 1263, in noble emulation of their predecessors of 1215, had risen in defence of the nation’s liberties, and the last hand was put to the building up of our present constitution, by the summoning, “to consult on public affairs,” of certain burgesses from the towns, in addition to the prelates, knights, and freeholders who had hitherto constituted the parliamentary body. But those barons and tenants-in-chief attended in their own right, and were altogether independent of the principle of election and representation. |A.D. 1265.|The summons issued by Simon de Montfort (son of the truculent hero of the Albigensian crusade, and brother-in-law of Henry) invested with new privileges the already-enfranchised boroughs. From this time the representatives of the Commons are always mentioned in the history of parliaments; and although this proceeding of De Montfort was only intended to strengthen his hands against his enemies, and, after his temporary object was gained, was not designed to have any further effect on the constitutional progress of our country, still, the principle had been adopted, the example was set, and the right to be represented in Parliament became one of the most valued privileges of the enfranchised commons.

It is observable that this increase of civil freedom in the various countries of Europe was almost in exact proportion to the diminution of ecclesiastical power. It is equally observable that the weakening of the priestly influence rapidly followed the infamous excesses into which its intolerance and pride had hurried the princes and other supporters of its claims. Never, indeed, had it appeared in so palmy and flourishing a state as in the course of this century; and yet the downward journey was begun. The devastation it carried into Languedoc, and the depopulation of all those sunny regions near the Mediterranean Sea—the crusades against the Saracens in Asia, to which it sent the strength of Europe, and against the Moors in Africa, to which it impelled the most obedient, and also, when his religious passions were roused, the most relentless, of the Church’s sons, no other than St. Louis—and the submission of the Patriarchates of Jerusalem and Alexandria to the Romish See—these and other victories of the Church were succeeded, before the century closed, by a manifest though silent insurrection against its spiritual domination. There were many reasons for this. The inferior though still dignified clergy in the different nations were alienated by the excessive exactions of their foreign head. In France the submissive St. Louis was forced to become the guardian of the privileges and income of the Gallican Church. In England the number of Italian incumbents exceeded that of the English-born; and in a few years the Pope managed to draw from the Church and State an amount equal to fifteen millions of our present coin. In Scotland, poorer and more proud, the king united himself to his clergy and nobles, and would not permit the Romish exactors to enter his dominions. The avarice and venality of Rome were repulsive equally to priest and layman. The strong support, also, which hitherto had arisen to the Holy See from the innumerable monks and friars, could no longer be furnished by the depressed and vitiated communities whom the coarsest of the common people despised for their sensuality and vice. In earlier times the worldly pretensions of the secular clergy were put to shame by the poverty and self-denial of the regular orders. Their ascetic retirement, and fastings, and scourgings, had recommended them to the peasantry round their monasteries, by the contrast their peaceful lives presented to the pomp and self-indulgence of bishops and priests. But now the character of the two classes was greatly changed. The parson of the parish, when he was not an Italian absentee, was an English clergyman, whose interests and feelings were all in unison with those of his flock; the monks were an army of mercenary marauders in the service of a foreign prince, advocating his most unpopular demands and living in the ostentatious disregard of all their vows. Even the lowest class of all, the thralls and villeins, were not so much as before in favour of their tonsured brothers, who had escaped the labours of the field by taking refuge in the abbey; for Magna Charta had given the same protection against oppression to themselves, and the enfranchisement of the boroughs had put power into the hands of citizens and freemen, who would not be so apt to abuse it as the martial baron or mitred prelate had been. The same principles were at work in France; and when the newly-established Franciscans and Dominicans were pointed to as restoring the purity and abnegation of the monks of old, the time for belief in those virtues being inherent, or even possible, in a cloister, was past, and little effect was produced in favour of Rome by the bloodthirsty brotherhood of the ferocious St. Dominic or the more amiable professions of the half-witted St. Francis of Assisi. |A.D. 1272.|The tide, indeed, had so completely turned after the commencement of the reign of Edward the First, that the Churchmen, both in England and France, preferred being taxed by their own Sovereign to being subjected to the arbitrary exactions of the Pope. Edward gave them no exemption from the obligation to support the expenses of the State in common with all the other holders of property, and pressed, indeed, rather more heavily upon the prelates and rich clergy than on the rest of the contributors, as if to drive to a decision the question, to which of the potentates—the Pope or the sovereign—tribute was lawfully due. When this object was gained, a bull was let loose upon the sacrilegious monarch by Boniface the Eighth, which positively forbids any member of the priesthood to contribute to the national exchequer on any occasion or emergency whatever. But the king made very light of the papal authority when it stood between him and the revenues of his crown, and the national clergy submitted to be taxed like other men. In France the same discussion led to the same result. The Gallican and English Churches asserted their liberties in a way which must have been peculiarly gratifying to the kings,—namely, by subsidies to the Crown, and disobedience to the fulminations of the Pope.

But no surer proof of the increased wisdom of mankind can be given than the termination of the Crusades. Perhaps, indeed, it was found that religious excitement could be combined with warlike distinction by assaults on the unbelieving or disobedient at home. There seemed little use in traversing the sea and toiling through the deserts of Syria, when the same heavenly rewards were held out for a campaign against the inhabitants of Languedoc and the valleys of the Alps. Clearer views also of the political effect of those distant expeditions in strengthening the hands of the Pope, who, as spiritual head of Christendom, was ex officio commander of the crusading armies, must no doubt have occurred to the various potentates who found themselves compelled to aid the very authority from whose arrogance they suffered so much. The exhaustion of riches and decrease of population were equally strong reasons for repose. But none of all these considerations had the least effect on the simple and credulous mind of Louis the Ninth. Resisting as he did the interference of the Pope in his character of King of France, no one could yield more devoted submission to the commands of the Holy Father when uttered to him in his character of Christian knight. At an early age he vowed himself to the sacred cause, and in the year 1248 the seventh and last crusade to the Holy Land took its way from Aigues-Mortes and Marseilles, under the guidance of the youthful King and the Princes of France. Disastrous to a more pitiful degree than any of its predecessors, this expedition began its course in Egypt by the conquest of Damietta, and from thenceforth sank from misery to misery, till the army, surprised by the inundations of the Nile, and hemmed in by the triumphant Mussulmans, surrendered its arms, and the nobility of France, with its king at its head, found itself the prisoner of Almohadam. An insurrection in a short time deprived their conqueror of life and crown, and a treaty for the payment of a great ransom set the captives free. Ashamed, perhaps, to return to his own country, sighing for the crown of martyrdom, zealous at all events for the privileges of a pilgrim, Louis betook himself to Palestine, and, as he was bound by the convention not to attack Jerusalem, he wasted four years in uselessly rebuilding the fortifications of Ptolemais, and Sidon, and Jaffa, and only embarked on his homeward voyage when the death of his mother and the discontent of his subjects necessitated his return. |A.D. 1254.|After an absence of six years, the enfeebled and exhausted king sat once more in the chair of judgment, and gained all hearts by his generosity and truth. Yet the old fire was not extinct. His oath was binding still, and in 1270, girt with many a baron bold, and accompanied by his brother, Charles of Anjou, and the gay Prince Edward of England, he fixed the red cross upon his shoulder and led his army to the sea-shore. The ships were all ready, but the destination of the war was changed. A new power had established itself at Tunis, more hostile to Christianity than the Moslem of Egypt, and nearer at hand. In an evil hour the King was persuaded to attack the Tunisian Caliph. He landed at Carthage, and besieged the capital of the new dominion. But Tunis witnessed the death of its besieger, for Louis, worn out with fatigue and broken with disappointment, was stricken by a contagious malady, and expired with the courage of a hero and the pious resignation of a Christian. With him the crusading spirit vanished from every heart. All the Christian armies were withdrawn. The Knights-Hospitallers, the Templars, the Teutonic Order, passed over to Cyprus, and left the hallowed spots of sacred story to be profaned by the footsteps of the Infidel. Asia and Europe henceforth pursued their separate courses; and it was left to the present day to startle the nations of both quarters of the world with the spectacle of a war about the possession of the Holy Places.

The century which has the slaughter of the Albigenses, the Magna Charta, the rise of the Commons, the termination of the Crusades, to distinguish it, will not need other features to be pointed out in order to abide in our memories. Yet the reign of Edward the First, the greatest of our early kings, must be dwelt on a little longer, as it would not be fair to omit the personal merits of a man who united the virtues of a legislator to those of a warrior. Whether it was the prompting of ambition, or a far-sighted policy, which led him to attempt the conquest of Scotland, we need not stop to inquire. It might have satisfied the longings both of policy and ambition if he had succeeded in creating a compact and irresistible Great Britain out of England harassed and Scotland insecure. And if, contented with his undivided kingdom, he had devoted himself uninterruptedly to the introduction and consolidation of excellent laws, and had extended the ameliorations he introduced in England to the northern portion of his dominions, he would have earned a wider fame than the sword has given him, and would have been received with blessings as the Justinian of the whole island, instead of establishing a rankling hatred in the bosoms of one of the cognate peoples which it took many centuries to allay, if, indeed, it is altogether obliterated at the present time; for there are not wanting enthusiastic Scotchmen who show considerable wrath when treating of his assumptions of superiority over their country and his interference with their national affairs.

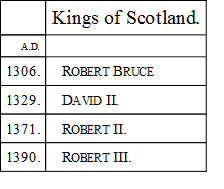

Edward’s sister had been the wife of Alexander the Third of Scotland. Two sons of that marriage had died, and the only other child, a daughter, had married Eric the Norwegian. In Margaret, the daughter of this king, the Scottish succession lay, and when her grandfather died in 1290, the Scottish states sent a squadron to bring the young queen home, and great preparations were made for the reception of the “Maid of Norway.” But the Maid of Norway was weak in health; the voyage was tempestuous and long; and weary and exhausted she landed on one of the Orkney Islands, and in a short time a rumour went round the land that the hope of Scotland was dead. Edward was among the first to learn the melancholy news. He determined to assert his rights, and began by trying to extend the feudal homage which several of the Scottish kings had rendered for lands held in England, over the Scottish crown itself. When the various competitors for the vacant throne submitted their pretensions to his decision he made their acknowledgment of his supremacy an indispensable condition. Out of the three chief candidates he fixed on John Baliol, who, in addition to the most legal title, had perhaps the equal recommendation of being the feeblest personal character. Robert Bruce and Hastings, the other candidates, submitted to their disappointment, and Baliol became the mere viceroy of the English king. He obeyed a summons to Westminster as a vassal of Edward, to answer for his conduct, and was treated with disdain. |A.D. 1293.|But the Scottish barons had more spirit than their king. They forced him to resist the pretensions of his overbearing patron, and for the first time, in 1295, began the long connection between France and Scotland by a treaty concluded between the French monarch and the twelve Guardians of Scotland, to whom Baliol had delegated his authority before retiring forever to more peaceful scenes. From this time we find that, whenever war was declared by France on England, Scotland was let loose on it to distract its attention, in the same way as, whenever war was declared upon France, the hostility of Flanders was roused against its neighbour. But the benefits bestowed by England on her Low Country ally were far greater than any advantage which France could offer to Scotland. Facilities of trade and favourable tariffs bound the men of Ghent and Bruges to the interests of Edward. But the friendship of France was limited to a few bribes and the loan of a few soldiers. Scotland, therefore, became impoverished by her alliance, while Flanders grew fat on the liberality of her powerful friend. England itself derived no small benefit both from the hostility of Scotland and the alliance of the Flemings. When the Northern army was strong, and the King was hard pressed by the great Wallace, the sagacious Parliament exacted concessions and immunities from its imperious lord before it came liberally to his aid; and whenever we read in one page of a check to the arms of Edward, we read in the next of an enlargement of the popular rights. When the first glow of the apparent conquest of Scotland was past, and the nation was seen rising under the Knight of Elderslie after it had been deserted by its natural leaders, the lords and barons,—and, later, when in 1297 he gained a great victory over the English at Stirling,—the English Parliament lost no time in availing themselves of the defeat, and sent over to the king, who was at the moment in Flanders menacing the flanks of France, a parchment for his signature, containing the most ample ratification of their power of granting or withholding the supplies. It was on the 10th of October, 1297, that this important document was signed; and, satisfied with this assurance of their privileges, the “nobles, knights of the shire, and burgesses of England in parliament assembled” voted the necessary funds to enable their sovereign lord to punish his rebels in Scotland. Perhaps these contests between the sister countries deepened the patriotic feeling of each, and prepared them, at a later day, to throw their separate and even hostile triumphs into the united stock, so that, as Charles Knight says in his admirable “Popular History,” “the Englishman who now reads of the deeds of Wallace and Bruce, or hears the stirring words of one of the noblest lyrics of any tongue, feels that the call to ‘lay the proud usurper low’ is one which stirs his blood as much as that of the born Scotsman; for the small distinctions of locality have vanished, and the great universal sympathies for the brave and the oppressed stay not to ask whether the battle for freedom was fought on the banks of the Thames or of the Forth. The mightiest schemes of despotism speedily perish. The union of nations is accomplished only by a slow but secure establishment of mutual interests and equal rights.”

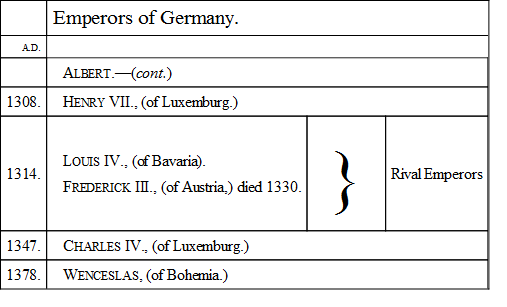

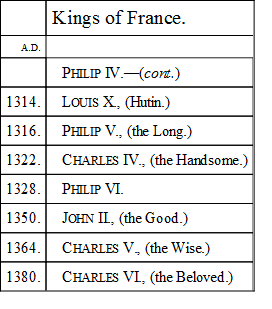

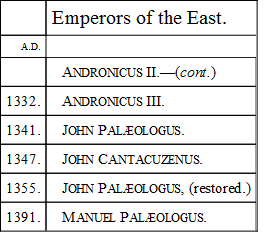

FOURTEENTH CENTURY

Dante, Petrarch, Boccaccio, Chaucer, Froissart, John Duns Scotus, Bradwardine, William Occam, Wickliff.

THE FOURTEENTH CENTURY

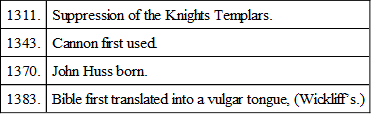

ABOLITION OF THE ORDER OF THE TEMPLARS – RISE OF MODERN LITERATURES – SCHISM OF THE CHURCHIn the year 1300 a jubilee was celebrated at Rome, when remission of sins and other spiritual indulgences were offered to all visitors by the liberal hand of Pope Boniface the Eighth. And for the thirty days of the solemn ceremonial, the crowds who poured in from all parts of Europe, and pursued their way from church to church and kissed with reverential lips the relics of the saints and martyrs, gave an appearance of strength and universality to the Roman Church which had long departed from it. Yet the downward course had been so slow, and each defection or defeat had been so covered from observation in a cloud of magnificent boasts, that the real weakness of the Papacy was only known to the wise and politic. Even in the splendours and apparent triumph of the jubilee processions it was perceived by the eyes of hostile statesmen that the day of faith was past.

Dante, the great poet of Italy, was there, piercing with his Ithuriel spear the false forms under which the spiritual tyranny concealed itself. Countless multitudes deployed before him without blinding him for a moment to the unreality of all he saw. Others were there, not deriving their conclusions, like Dante, from the intuitive insight into truth with which the highest imaginations are gifted, but from the calmer premises of reason and observation. Even while the pæans were loudest and the triumph at its height, thoughts were entering into many hearts which had never been harboured before, but which in no long space bore their fruits, not only in opposition to the actual proceedings of Rome, but in undisguised contempt and ridicule of all its claims. Boniface himself, however, was ignorant of all these secret feelings. He was now past eighty years of age, and burning with a wilder personal ambition and more presumptuous ostentation than would have been pardonable at twenty. He appeared in the processions of the jubilee, dressed in the robes of the Empire, with two swords, and the globe of sovereignty carried before him. A herald cried, at the same time, “Peter, behold thy successor! Christ, behold thy vicar upon earth!” But the high looks of the proud were soon to be brought low. The King of France at that time was Philip the Handsome, the most unprincipled and obstinate of men, who stuck at no baseness or atrocity to gain his ends,—who debased the Crown, pillaged the Church, oppressed the people, tortured the Jews, and impoverished the nobility,—a self-willed, strong-handed, evil-hearted despot, and glowing with an intense desire to humble and spoil the Holy Father himself. If he could get the Pope to be his tax-gatherer, and, instead of emptying the land of all its wealth for the benefit of the Roman exchequer, pour Roman, German, English, European contributions into his private treasury, the object of his life would be gained. His coffers would be overflowing, and his principal opponent disgraced. A wonderful and apparently impossible scheme, but which nevertheless succeeded. The combatants at first seemed very equally matched. When Boniface made an extravagant demand, Philip sent him a contemptuous reply. When Boniface turned for alliances to the Emperor or to England, Philip threw himself on the sympathy of his lords and the inhabitants of the towns; for the parts formerly played by Pope and King were now reversed. The Papacy, instead of recurring to the people and strengthening itself by contact with the masses who had looked to the Church as their natural guard from the aggressions of their lords, now had recourse to the more dangerous expedient of exciting one sovereign against another, and weakened its power as much by concessions to its friends as by the hostility of its foes. The king, on the other hand, flung himself on the support of his subjects, including both the Church and Parliament, and thus raised a feeling of national independence which was more fatal to Roman preponderance than the most active personal enmity could have been. Accordingly, we find Boniface offending the population of France by his intemperate attacks on the worst of kings, and that worst of kings attracting the admiration of his people by standing up for the dignity of the Crown against the presumption of the Pope. The fact of this national spirit is shown by the very curious circumstance that while Philip and his advisers, in their quarrels with Boniface, kept within the bounds of respectful language in the letters they actually sent to Rome, other answers were disseminated among the people as having been forwarded to the Pope, outraging all the feelings of courtesy and respect. It was like the conduct of the Chinese mandarins, who publish vainglorious and triumphant bulletins among their people, while they write in very different language to the enemy at their gates. Thus, in reply to a very insulting brief of Boniface, beginning, “Ausculta, fili,” (Listen, son,) and containing a catalogue of all his complaints against the French king, Philip published a version of it, omitting all the verbiage in which the insolent meaning was involved, and accompanied it in the same way with a copy of the unadorned eloquence which constituted his reply. In this he descended to very plain speaking. “Philip,” he says, “by the grace of God, King of the French, to Boniface, calling himself Pope, little or no salutation. Be it known to your Fatuity that we are subject in temporals to no man alive; that the collation of churches and vacant prebends is inherent in our Crown; that their ‘fruits’ belong to us; that all presentations made or to be made by us are valid; that we will maintain our presentees in possession of them with all our power; and that we hold for fools and idiots whosoever believes otherwise.” This strange address received the support of the great majority of the nation, and was meant as a translation into the vulgar tongue of the real intentions of the irritated monarch, which were concealed in the letter really despatched in a mist of polite circumlocutions. Boniface perceived the animus of his foe, but bore himself as loftily as ever. When a meeting of the barons, held in the Louvre, had appealed to a General Council and had passed a vote of condemnation against the Pope as guilty of many crimes, not exclusive of heresy itself, he answered, haughtily, that the summoning of a council was a prerogative of the Pope, and that already the King had incurred the danger of excommunication for the steps he had taken against the Holy Chair. To prevent the publication of the sentence, which might have been made a powerful weapon against France in the hands of Albert of Germany or Edward of England, it was necessary to give notice of an appeal to a General Council into the hands of the Pope in person. He had retired to Anagni, his native town, where he found himself more secure among his friends and relations than in the capital of his See. Colonna, a discontented Roman and sworn enemy of Boniface, and Supino, a military adventurer, whom Philip bought over with a bribe of ten thousand florins, introduced Nogaret, the French chancellor and chief adviser of the king, into Anagni, with cries from their armed attendants of “Death to the Pope!” “Long live the King of France!” The cardinals fled in dismay. The inhabitants, not being able to prevent their visitors from pillaging the shops, joined them in that occupation, and every thing was in confusion. The Pope was in despair. His own nephew had abandoned his cause and made terms for himself. Accounts vary as to his behaviour in these extremities. Perhaps they are all true at different periods of the scene. At first, overwhelmed with the treachery of his friends, he is said to have burst into tears. Then he gathered his ancient courage, and, when commanded to abdicate, offered his neck to the assailants; and at last, to strike them with awe, or at least to die with dignity, he bore on his shoulders the mantle of St. Peter, placed the crown of Constantine on his head, and grasped the keys and cross in his hands. Colonna, they say, struck him on the cheek with his iron gauntlet till the blood came. Let us hope that this is an invention of the enemy; for the Pope was eighty-six years old, and Colonna was a Roman soldier. There is always a tendency to elevate the sufferer in the cause we favour, by the introduction of ennobling circumstances. In this and other instances of the same kind there is the further temptation in orthodox historians to make the most they can of the martyrdom of one of their chiefs, and in a peculiar manner to glorify the wrongs of their hero by their resemblance to the sufferings of Christ. But the rest of the story is melancholy enough without the aggravation of personal pain. The pontiff abstained from food for three whole days. He consumed his grief in secret, and was only relieved at last from fears of the dagger or poison by an insurrection of the people. They fell upon the French escort when they perceived how weak it was, and carried the Pope into the market-place. He said, “Good people, you have seen how our enemies have spoiled me of my goods. Behold me as poor as Job. I tell you truly, I have nothing to eat or drink. If there is any good woman who will charitably bestow on me a little bread and wine, or even a little water, I will give her God’s blessing and mine. Whoever will bring me the smallest thing in this my necessity, I will give him remission of all his sins.” All the people cried, “Long live the Holy Father!” They ran and brought him bread and wine, and any thing they had. Everybody would enter and speak to him, just as to any other of the poor. In a short time after this he proceeded to Rome, and felt once more in safety. But his heart was tortured by anger and a thirst for vengeance. He became insane; and when he tried to escape from the restraints his state demanded, and found his way barred by the Orsini, his insanity became madness. He foamed at the mouth and ground his teeth when he was spoken to. He repelled the offers of his friends with curses and violence, and died without the sacraments or consolations of the Church. |A.D. 1303.|The people remembered the prophecy made of him by his predecessor Celestin:—“You mounted like a fox; you will reign like a lion; you will die like a dog.”