полная версия

полная версияThe Eighteen Christian Centuries

THIRTEENTH CENTURY

Roger Bacon, Matthew Paris, Alexander Hales, (Irrefragable Doctor,) Thomas Aquinas, (the Angelic Doctor.)

THE THIRTEENTH CENTURY

FIRST CRUSADE AGAINST HERETICS – THE ALBIGENSES – MAGNA CHARTA – EDWARD IThe progress and enlightenment of Europe proceed from this period at a constantly-increasing rate. The rise of commercial cities, the weakening of the feudal aristocracy, the introduction of the learning of the Saracenic schools, and the growth of universities for the cultivation of science and language, contributed greatly to the result. Another cause used to be assigned for this satisfactory advance, in the discovery which had been made in the last century at Amalfi, of a copy of the long-forgotten Pandects of Justinian, and the reintroduction of the Roman laws, in displacement of the conflicting customs and barbarous enactments of the various states; but the fact of the continued existence of the Roman Institutes is not now denied, though it is probable that the discovery of the Amalfi manuscript may have given a fresh impulse to the improvement of the local codes. But an increase of mental activity had at first its usual regretable accompaniment in the contemporaneous rise of dangerous and unfounded opinions. Philosophy, which began with an admiration of the skill and learning of Aristotle, ended by enthroning him as the uncontrolled master of human reason. Wherever he was studied, all previous standards of faith and argument were overthrown. The cleverest intellects of the time could find themselves no higher task than to reconcile the Christian Scriptures with the decrees of the Stagyrite, for it was felt that in the case of an irreconcilable divergence between the teaching of Christ and of Aristotle the scholars of Christendom would have pronounced in favour of the Greek. A formulary, indeed, was found out for the joint reception of both; many statements were declared to be “true in philosophy though false in religion,” so that the most orthodox of Churchmen could receive the doctrines of the Church by an act of belief, while he gave his whole affection to Aristotle by an act of the understanding. When teachers and preachers tamper with the human conscience, the common feelings of honour and fair play revolt at the degrading attempt. Men of simple minds, who did not profess to understand Aristotle and could not be blinded by the subtleties of logic, endeavoured to discover “the more excellent way” for themselves, but were bewildered by the novelty of their search for Truth. There were mystic dreamers who saw God everywhere and in every thing, and counted human nature itself a portion of the Deity, or maintained that it was possible for man to attain a share of the divine by the practice of virtue. This Pantheism gave rise to numerous displays of popular ignorance and impressibility. Messiahs appeared in many parts of Europe, and were followed by great multitudes. Some enthusiasts taught that a new dispensation was opening upon man; that God was the Governor of the world during the Old Testament period; that Christ had reigned till now, but that the reign of the Holy Spirit was about to commence, and all things would be renewed. Others, more hardy, declared their adhesion to the Persian principle of a duality of persons in heaven, and revived the old Manichean heresy that the spirit of Hatred was represented in the Jewish Scriptures and the spirit of Love in the Christian; that the Good god had created the soul, and the Evil god the body,—on which were justified the sufferings they voluntarily inflicted on the workmanship of Satan, and the starvings and flagellations required to bring it into subjection. This belief found few followers, and would have died out as rapidly as it had arisen; but the malignity of the enemies of any change found it convenient to identify those wild enthusiasts with a very different class of persons who at this time rose into prominent notice. The rich counties of the South of France were always distinguished from the rest of the nation by the possession of greater elegance and freedom. The old Roman civilization had never entirely deserted the shores of the Mediterranean or the valleys of Languedoc and Provence. In Languedoc a sect of strange thinkers had given voice to some startling doctrines, which at once obtained the general consent. Toulouse was the chief encourager of these new beliefs, and in its hostility to Rome was supported by its reigning sovereign, Count Raymond VI. This potentate, from the position of his States,—abutting upon Barcelona, where the Spaniards, who remembered their recent emancipation from the Mohammedan yoke, were famous for their tolerance of religious dissent,—and deriving the greater portion of his wealth from the trade and industry of the Jews and Arabs established in his seaport towns, saw no great evil in the principles professed by his people. Those principles, indeed, when stripped of the malicious additions of his enemies, were not different from the creed of Protestantism at the present time. They consisted merely of a complete denial of the sovereignty of the Pope, the power of the priesthood, the efficacy of prayers for the dead, and the existence of purgatory.

The other princes of the South looked on religion as a mere instrument for the advancement of their own interests, and would have imitated the greater sovereigns of Europe, several of whom for a very slender consideration would have gone openly over to the standard of Mohammed. The inhabitants, therefore, of those opulent regions, by the favour of Raymond and the indifference of the rest, were left for a long time to their own devices, and gave intimation of a strong desire to break off their connection with the hierarchy of Rome. And no wonder they were tired of their dependence on so grasping and unprincipled a power as the Church had proved to them. More depraved and more exacting in this district than in any other part of Europe, the clergy had contrived to alienate the hearts of the common people without gaining the friendship of the nobility. Equally hated by both,—despised for their sensuality, and no longer feared for their spiritual power,—the priests could offer no resistance to the progress of the new opinions. Those opinions were in fact as much due to the vices of the clergy as to the convictions of the congregations. Any thing hostile to Rome was welcomed by the people. A musical and graceful language had grown up in Languedoc, which was universally recognised as the fittest vehicle for descriptions of beauty and declarations of love, and had been found equally adapted for the declamations of political hatred and denunciations of injustice. But now the whole guild of troubadours, ceasing to dedicate their muses to ladies’ charms or the quarrels of princes, poured forth their indignation in innumerable songs on their clerical oppressors. The infamies of the whole order—the monks black and white, the deacons, the abbots, the bishops, the ordinary priests—were now married to immortal verse. Their spoiling of orphans, their swindling of widows and wards, their gluttony and drunkenness, were chronicled in every township, and were incapable of denial. Their dishonesty became proverbial. The simplest peasant, on hearing of a scandalous action, was in the habit of saying, “I would rather be a priest than be guilty of such a deed.” But there were two men then alive exactly adapted to meet the exigencies of the time. One was a noble Castilian of the name of Dominic Guzman, who had become disgusted with the world, and had taken refuge from temptations and strife among the brethren of a reformed cathedral in Spain. But temptations and strife forced their way into the cells of Asma, and the eloquent friar was torn away from his prayers and penances and brought prominently forward by the backslidings of the men of Languedoc. The saturnine and self-sacrificing Spaniard had no sympathy with the joyous proceedings of the princes and merchants of the South. He saw sin in their enjoyment even of the gifts of nature,—their gracious air and beautiful scenery. How much more when the gayety of their meetings was enlivened by interludes throwing ridicule on the pretensions of the bishops, by hootings at any ecclesiastic who presented himself in the street, and by sneers and loud laughter at the predictions and miracles with which the Church resisted their attack! The unbelieving populace did not spare the personal dignity of the missionary himself. They pelted him with mud, and fixed long tails of straw at the back of his robe; they outraged all the feelings of his heart, his Castilian pride, his Christian belief, his clerical obedience. There is no denying the energy with which he exerted himself to recall those wandering sheep to the true fold. His biographer tells us of the successes of his eloquence, and of the irresistible effect of the inexhaustible fountain of tears with which he inundated his face till they formed a river down to his robes. His writings, we are assured, being found unanswerable by the heretics, were submitted to the ordeal of fire. Twice they resisted the hottest flames which could be raised by wood and brimstone, and still without converting the incredulous subjects of Count Raymond. His miracles, which were numerous and undeniable, also had no effect. Even his prayers, which seem to have moved houses and walls, had no efficacy in moving the obdurate hearts of the unbelievers; and at last, tired out with their recalcitrancy, the dreadful word was spoken. He cursed the men of Languedoc, the inhabitants of its towns, the knights and gentlemen who received his oratory with insult, and in addition to his own anathemas called in the spiritual thunder of the Pope.

This was the other man peculiarly fitted for the work he had to do. His cruelty would have done no dishonour to the blood-stained scutcheon of Nero, and his ambition transcended that of Gregory the Seventh. His name was Innocent the Third. |A.D. 1207.|For one-half of the crimes alleged against those heretics, who, from their principal seat in the diocese of Albi, were known as Albigenses, he would have turned the whole of France into a desert; and when, with greedy ear, he heard the denunciations of Dominic, he declared war on the devoted peasants,—war on the consenting princes; a holy war—more meritorious than a Crusade against the Turks and infidels—where no life was to be spared, and where houses and lands were to be the reward of the assailants. All the wild spirits of the age were wakened by the call. It was a pilgrimage where all expenses were paid, without the danger of the voyage to the East or the sword of the Saracen. Foremost among those who hurried to this mingled harvest of money and blood, of religious absolution and military fame, was the notorious Simon de Montfort, a man fitted for the commission of any wickedness requiring a powerful arm and unrelenting heart. Forward from all quarters of Europe rushed the exterminating emissaries of the Pope and soldiers of Dominic. “You shall ravage every field; you shall slay every human being: strike, and spare not. The measure of their iniquity is full, and the blessing of the Church is on your heads.” These words, sung in sweet chorus by the Pope and the Monk, were the instructions on which De Montfort was prepared to act; and what could the sunny Languedoc, the land of song and dance, of olive-yard and vineyard, do to repel this hostile inroad? Suddenly all the music of the troubadours was hushed in dreadful expectation. Raymond was alarmed, and tried to temporize. |A.D. 1208.|Promises were made and explanations given, but without any offer of submission to the yoke of Rome: so the infuriated warriors came on, burning, slaying, ravaging, in terms of their commission, till Dominic himself grew ashamed of such blood-stained missionaries; and when their slaughters went on, when they had murdered half the population in cold blood, and ridden down the peasantry whom despair had summoned to the defence of their houses and properties, the saintly-minded Spaniard could no longer honour their hideous butcheries with his presence. He contented himself with retiring to a church and praying for the good cause with such zeal and animation that De Montfort and eleven hundred of his ruffians put to flight a hundred thousand of the armed soldiers of the South, who felt themselves overthrown and scattered by an invisible power. Yet not even the prayers of Dominic could keep the outraged people in unresisting acquiescence. Simon de Montfort was expelled from the territories he had usurped, and found a mysterious death under the walls of Toulouse in 1218.

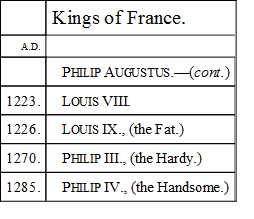

|A.D. 1223.|

The old family was restored in the person of Raymond the Seventh, and preparations made for defence. But Louis the Eighth of France came to the aid of the infuriated Pope. Two hundred thousand men followed in the holy campaign. All the atrocities of the former time were renewed and surpassed. Town after town yielded, for all the defenders had died. Pestilence broke out in the invading force, and Louis himself was carried off by fever. Champions, however, were ready in all quarters to carry on the glorious cause. Louis the Ninth was now King of France, and under the government of his mother, Blanche of Castile, the work commenced by her countryman was completed. The final victory of the crusaders and punishment of the rebellious were celebrated by the introduction of the Inquisition, of which the ferocious Dominic was the presiding spirit. The fire of persecution under his holy stirrings burnt up what the sword of the destroyer had left, and from that time the voice of rejoicing was heard no more in Languedoc: her freedom of thought and elegance of sentiment were equally crushed into silence by the heel of persecution. The “gay science” perished utterly; the very language in which the sonnets of knight and troubadour had been composed died away from the literatures of the earth; and Rome rejoiced in the destruction of poetry and the restoration of obedience. This is a very mark-worthy incident in the thirteenth century, as it is the first experiment, on a great scale, which the Church made to retain her supremacy by force of arms. The pagan and infidel, the denier of Christ and the enemies of his teaching, had hitherto been the objects of the wrath of Christendom. This is the first instance in which a difference of opinion between Christians themselves had been the ground for wholesale extermination; for those unfortunate Albigenses acknowledged the divinity of the Saviour and professed to be his disciples. It is the crowning proof of the totally-secularized nature of the established faith. Its weapons were no longer argument and proof, or even persuasion and promise. The horse up to his fetlocks in blood, the sword waved in the air, the trampling of marshalled thousands, were henceforth the supports of the religion of love and charity; and fires glowing in every market-place and dungeons gaping in every episcopal castle were henceforth the true expositors of the truth as it is in Jesus. Fires, indeed, and dungeons, were required to compensate for the incompleteness, as it appeared to the truly orthodox, of the vengeance inflicted on the rebels. The Abbot of Citeaux, who gave his spiritual and corporeal aid to the assault on Beziers, was for a moment made uneasy by the difficulty his men experienced in distinguishing between the heretics and believers at the storm of the town. At last he got out of the difficulty by saying, “Slay them all! The Lord will know his own.” The same benevolent dignitary, when he wrote an account of his achievement to the Pope, lamented that he had only been able to cut the throats of twenty thousand. And Gregory the Ninth would have been better pleased if it had been twice the number. “His vast revenge had stomach for them all,” and already a quarter of a million of the population were the victims of his anger. Every thing had prospered to his hand. Raymond was despoiled of the greater portion of his estates, the voice of opposition was hushed, the castles of the nobles confiscated to the Church; and yet, when the treaty of Meaux, in 1229, by which the war was concluded, came to be considered, it was perceived that the pacification of Languedoc turned not so much to the profit of Rome as of the rapidly-coalescing monarchy of France.

Long before this, in 1204, Philip Augustus had found little difficulty in tearing the continental possessions of the English crown, except Guienne, from the trembling hands of John. The possession of Normandy had already made France a maritime power; and now, by the acquisition of the Narbonnais and Maguelonne from Raymond the Seventh, she not only extended her limits to the Mediterranean, but, by the extinction of two such vassals as the Count of Toulouse and the Duke of Normandy, incalculably strengthened the royal crown. Extinguished, indeed, was the power of Toulouse; for by the same treaty the unfortunate Raymond bought his peace with Rome by bestowing the county of Venaissin and half of Avignon on the Holy See. These sacrifices relieved him from the sentence of excommunication, and made him the best-loved son of the Church, and the poorest prince in Christendom.

While monarchy was making such strides in France, a counterbalancing power was formed in England by the combination of the nobility and the rise of the House of Commons. The story of Magna Charta is so well known that it will be sufficient to recall some of its principal incidents, which could not with propriety be omitted in an account of the important events of the thirteenth century. No event, indeed, of equal importance occurred in any other country of Europe. However more startling a crusade or a victory might be at the time, the results of no single incident have ever been so enduring or so wide-spread as those of the meeting of the barons at Runnymede and the summoning of the burgesses to Parliament.

The whole reign of John (1199-1216) is a tale of wickedness and degradation. Richard of the Lion-Heart had been cruel and unprincipled; but the sharpness of his sword threw a sort of respectability over the worst portions of his character. His practical talents, also, and the romantic incidents of his life, his confinement, and even of his death, lifted him out of the ordinary category of brutal and selfish kings and converted a very ferocious warrior into a popular hero. But John was hateful and contemptible in an equal degree. He deserted his father, he deceived his brother, he murdered his nephew, he oppressed his people. He had the pride that made enemies, and wanted the courage to fight them. A knight without truth, a king without justice, a Christian without faith,—all classes rebelled against him. Innocent the Third scented from afar the advantage he might obtain from a monarch whose nobility despised him and who was hated by his people. And when John got up a quarrel about the nomination of an archbishop to Canterbury, the Pope soon saw that though Langton was no à-Beckett, still less was John a Henry the Second. A sentence of excommunication was launched at the coward’s head, and the crown of England offered to Philip Augustus of France. Philip Augustus had the modesty to refuse the splendid bribe, and contented himself with aiding to weaken a throne he did not feel inclined to fill. It is characteristic of John, that in the agonies of his fear, and of his desire to gain support against his people, he hesitated between invoking the assistance of the Miramolin of Morocco and the Pope of Rome. As good Mussulman with the one as Christian with the other, he finally decided on Innocent, and signed a solemn declaration of submission, making public resignation of the crowns of England and Ireland “to the Apostles Peter and Paul, to Innocent and his legitimate successors;” and, aided by the blessings of these new masters, and by the enforced neutrality of France, he was enabled to defeat his indignant nobles, and force them for two years to wear the same chains of submission to Rome which weighed upon himself. But in 1215 the patience of noble and peasant, of bishop and priest, was utterly exhausted. |A.D. 1215.|John fled on the first outburst of the collected storm, and thought himself fortunate in stopping its violence by signing the Great Charter, the written ratification of the liberties which had been conferred by some of his predecessors, but whose chief authority was in the traditions and customs of the land. This was not an overthrow of an old constitution and the substitution of a new and different code, but merely a formal recognition of the great and fundamental principles on which only government can be carried on,—security of person and property, and the just administration of equitable laws. All orders in the State were comprehended in this national agreement. The Church was delivered from the exactions of the king, and left to an undisturbed intercourse on spiritual matters with her spiritual head. She was to have perfect freedom of election to vacant benefices, and the king’s rapacity was guarded against by a clause reducing any fine he might impose on an ecclesiastic to an accordance with his professional income, and not with the extent of his lay possessions. The barons, of course, took equal care of their own interests as they had shown for those of the Church. They corrected many abuses from which they suffered, in respect to their feudal obligations. They regulated the fines and quit-rents on succession to their fiefs, the management of crown wards, and the marriage of heiresses and widows. They insisted also on the assemblage of a council of the great and lesser barons, to consult for the general weal, and put some check on the disposal of their lands by their tenants, in order to keep their vassals from impoverishment and their military organization unimpaired. But when church and aristocracy were thus protected from the tyranny of the king, were the interests of the great mass of the people neglected? This has sometimes been argued against the legislators of Runnymede, but very unjustly; for as much attention was paid to the liberties and immunities of the municipal corporations and of ordinary subjects as to those of the prelates and lords. Every person had the right to dispose of his property by will. No arbitrary tolls could be exacted of merchants. All men might enter or leave the kingdom without restraint. The courts of law were no longer to be stationary at Westminster, to which complainants from Northumberland or Cornwall never could make their way, but were to travel about, bringing justice to every man’s door. They were to be open to every one, and justice was to be neither “sold, refused, nor delayed.” Circuits were to be held every year. No man was to be put on his trial from mere rumour, but on the evidence of lawful witnesses. No sentence could be passed on a freeman except by his peers in jury assembled. No fine could be imposed so exorbitant as to ruin the culprit. But the bishops and clergy, the nobility and their vassals, the corporations and freemen, were not the main bodies of the State; and the framers of Magna Charta have been blamed for neglecting the great majority of the population, which consisted of serfs or villeins. This accusation is, however, not true, even with respect to the words of the Charter; for it is expressly provided that the carts and working-implements of that class of the people shall not be seizable in satisfaction of a fine; and in its intention the accusation is more untenable still; for although the reformers of 1215 had no design of granting new privileges to any hitherto-unprivileged order and their work was limited to the legal re-establishment of privileges which John had attempted to overthrow, the large and liberal spirit of their declarations is shown by the notice they take of the hitherto-unconsidered classes. For the protection accorded to their ploughs and carts, which are specifically named in the Charter, ratified at once their right to hold property,—the first condition of personal freedom and independence,—and, by an analogy of reasoning, restrained their more immediate masters from tyranny and injustice. It could not be long before a man secured by the national voice in the possession of one species of property extended his rights over every thing else. If the law guaranteed him the plough he held, the cart he drove, the spade he plied, why not the house he occupied, the little field he cultivated? And if the poorest freeman walked abroad in the pride of independence, because the baron could no longer insult him, or the priest oppress him, or the king himself strip him of land and gear, how could he deny the same blessings to his neighbour, the rustic labourer, who was already master of cart and plough and was probably richer and better fed than himself?