полная версия

полная версияThe Eighteen Christian Centuries

It must have been evident to any far-seeing observer that some great change was in progress during the whole of this century, not so much from the results of Courtrai, or Crecy, or Poictiers, or the migration of the Pope to Avignon, or the increasing riches of the trading and manufacturing towns, as from the great uprising of the human mind which was shown by the almost simultaneous appearance of such stars of literature as Dante, and Petrarch, and Boccaccio, and our English Chaucer. I suppose no single century since has been in possession of four such men. Great geniuses, indeed, and great discoveries, seem to come in crops, as if a certain period had been fixed for their bursting into flower; and we find the same grand ideas engaging the intellects of men widely dispersed, so that a novelty in art or science is generally disputed between contending nations. But this synchronous development of power is symptomatic of some wide-spread tendency, which alters the ordinary course of affairs; and we see in the Canterbury Tales the dawning of the Reformation; in Shakspeare and Bacon the inauguration of a new order of government and manners; in Locke and Milton a still further liberation from the chains of a worn-out philosophy; in Watt, and Fulton, and Cartwright, we see the spread of civilization and power. In Walter Scott and Wordsworth, and the wonderful galaxy of literary stars who illuminated the beginning of this century, we see Waterloo and Peace, a widening of national sympathies, and the opening of a great future career to all the nations of the world. For nothing is so true an index of the state and prospects of a people as the healthfulness and honest taste of its literature. It was in this sense that Fletcher of Saltoun said, (or quoted,) “Give me the making of the ballads of a people, and I don’t care who makes the laws.” While we have such pure and wholesome literature as is furnished us by Hallam, and Macaulay, and Alison, by Tennyson, Dickens, Thackeray, and the rest, philosophy like Hamilton’s, and science like Herschel’s and Faraday’s, we have no cause to look forward with doubt or apprehension.

“Naught shall make us rueIf England to herself do rest but true.”But those pioneers of the Fourteenth Century had dangers and difficulties to encounter from which their successors have been free. It is a very different thing for authors to write for the applause of an appreciating public, and for them to create an appreciating public for themselves. Their audience must at first have been hostile. First, the critical and scholarly part of the world was offended with the bad taste of writing in the modern languages at all. Secondly, the pitch at which they struck the national note was too high for the ears of the vulgar. A correct and dignified use of the spoken tongue, the conveyance, in ordinary and familiar words, of lofty or poetical thoughts, filled both those classes with surprise. To the scholar it seemed good materials enveloped in a very unworthy covering. To “the general” it seemed an attempt to deprive them of their vernacular phrases and bring bad grammar and coarse expressions into disrepute. Petrarch was so conscious of this that he speaks apologetically of his sonnets in Italian, and founds his hope of future fame on his Latin verses. But more important than the poems of Dante and Chaucer, or the prose of Boccaccio, was the introduction of the new literature represented by Froissart. Hitherto chronicles had for the most part consisted of the record of such wandering rumours as reached a monastery or were gathered in the religious pilgrimages of holy men. Mingled, even the best of them, with the credulity of inexperienced and simple minds, their effect was lost on the contemporary generation by the isolation of the writers. Nobody beyond the convent-walls knew what the learned historians of the establishment had been doing. Their writings were not brought out into the light of universal day, and a knowledge of European society gathered point by point, by comparing, analyzing, and contrasting the various statements contained in those dispersed repositories. But at this time there came into notice the most inquiring, enterprising, picturesque, and entertaining chronicler that had ever appeared since Herodotus read the result of his personal travels and sagacious inquiries to the assembled multitudes of Greece.

John Froissart, called by the courtesy of the time Sir John, in honour of his being priest and chaplain, devoted a long life to the collection of the fullest and most trustworthy accounts of all the events and personages characteristic of his time. From 1326, when his labours commenced, to 1400, when his active pen stood still, nothing happened in any part of Europe that the Paul Pry of the period did not rush off to verify on the spot. If he heard of an assemblage of knights going on at the extremities of France or in the centre of Germany, of a tournament at Bordeaux, a court gala in Scotland, or a marriage festival at Milan, his travels began,—whether in the humble guise of a solitary horseman with his portmanteau behind his saddle and a single greyhound at his heels, as he jogged wearily across the Border, till he finally arrived in Edinburgh, or in his grander style of equipment, gallant steed, with hackney led beside him, and four dogs of high race gambolling round his horse, as he made his dignified journey from Ferrara to Rome. Wherever life was to be seen and painted, the indefatigable Froissart was to be found. Whatever he had gathered up on former expeditions, whatever he learned on his present tour, down it went in his own exquisite language, with his own poetical impression of the pomps and pageantries he beheld; and when at the end of his journey he reached the court of prince or potentate, no higher treat could be offered to the “noble lords and ladies bright” than to form a glittering circle round the enchanting chronicler and listen to what he had written. From palace to palace, from castle to castle, the unwearied “picker-up of unconsidered trifles” (which, however, were neither trifles nor unconsidered, when their true value became known, as giving life and reality to the annals of a whole period) pursued his happy way, certain of a friendly reception when he arrived, and certain of not losing his time by negligence or blindness on the road. If he overtakes a stately cavalier, attended by squires and men-at-arms, he enters into conversation, drawing out the experiences of the venerable warrior by relating to him all he knew of things and persons in which he took an interest. And when they put up at some hostelry on the road, and while the gallant knight was sound asleep on his straw-stuffed couch, and his followers were wallowing amid the rushes on the parlour floor, Froissart was busy with pen and note-book, scoring down all the old gentleman had told him, all the fights he had been present at, and the secret history (if any) of the councils of priests and kings. In this way knights in distant parts of the world became known to each other. The same voice which described to Douglas at Dalkeith the exploits of the Prince of Wales sounded the praises of Douglas in the ears of the Black Prince at Bordeaux. A community of sentiment was produced between the upper ranks of all nations by this common register of their acts and feelings; and knighthood received its most ennobling consummation in these imperishable descriptions, at the very time when its political and military influence came to a close. Froissart’s Chronicles are the epitaph of feudalism, written indeed while it was yet alive, but while its strength was only the convulsive energy of approaching death. The standard of knightly virtue became raised in proportion as knightly power decayed. In the same way as the increased civilization and elevating influences of the time clothed the Church in colours borrowed from the past, while its real influence was seriously impaired, the expiring embers of knighthood occasionally flashed up into something higher; and in this century we read of Du Guesclin of France, Walter Manny and Edward the Third of England, and many others, who illustrated the order with qualifications it had never possessed in its palmiest state.

Courtrai was fought and Amadis de Gaul written almost at the same time. Let us therefore mark, as a characteristic of the period we have reached, the decay of knighthood, or feudalism in its armour of proof, and the growth at the same time of a sense of honour and generosity, which contrasted strangely in its softened and sentimentalized refinement with the harshness and cruelty which still clung to the ordinary affairs of life. Thus the young conqueror of Poictiers led his captive John into London with the respectful attention of a grateful subject to a crowned king. He waited on him at table, and made him forget the humiliation of defeat and the griefs of imprisonment in the sympathy and reverence with which he was everywhere surrounded. This same prince was regardless of human life or suffering where the theatrical show of magnanimity was not within his reach, bloodthirsty and tyrannical, and is declared by the chronicler himself to be of “a high, overbearing spirit, and cruel in his hatred.” It shows, however, what an advance had already been made in the influence of public opinion, when we read how generally the treatment of the noble captive, John of France, was appreciated. In former ages, and even at present in nations of a lower state of feelings, the kind treatment of a fallen enemy, or the sparing of a helpless population, would be attributed to weakness or fear. Chivalry, which was an attempt to amalgamate the Christian virtues with the rougher requirements of the feudal code, taught the duty of being pitiful as well as brave. And though at this period that feeling only existed between knight and knight, and was not yet extended to their treatment of the common herd, the principle was asserted that war could be carried on without personal animosity, and that courage, endurance, and the other knightly qualities were to be admired as much in an enemy as a friend.

There was, however, another reason for this besides the natural admiration which great deeds are sure to call forth in natures capable of performing them; and that was, that Europe was divided into petty sovereignties, too weak to maintain their independence without foreign aid, too proud to submit to another government, and trusting to the support their money or influence could procure. In all countries, therefore, there existed bodies of mercenary soldiers—or Free Lances, as they were called—claiming the dignity and rank of knights and noblemen, who never knew whether the men they were fighting to-day might not be their comrades and followers to-morrow. In Italy, always a country of divisions and enmities, there were armed combatants secured on either side. Unconnected with the country they defended by any ties of kindred or allegiance, they found themselves opposed to a body, perhaps of their countrymen, certainly of their former companions; and, except so much as was required to earn their pay and preserve their reputation, they did nothing that might be injurious to their temporary foes. Battles accordingly were fought where feats of horsemanship and dexterity at their weapons were shown; where rushes were made into the vacant space between the armies by contending warriors, and horse and man acquitted themselves with the acclamations, and almost with the safety, of a charge in the amphitheatre at Astley’s. But no blood was spilt, no life was taken; and a long summer day has seen a confused mêlée going on between the hired combatants of two cities or principalities, without a single casualty more serious than a cavalier thrown from his horse and unable to rise from the weight and tightness of his armour. Fights of this kind could scarcely be considered in earnest, and we are not surprised to find that the burden and heat of an engagement was thrown upon the light-armed foot: we gather, indeed, towards the end of Froissart’s Chronicles, that while the cavaliers persisted in endeavouring to distinguish their individual prowess, as at the battle of Navareta in Spain, and got into confusion in their eagerness of assault, “the sharpness of the English arrows began to be felt,” and the fate of the battle depended on the unflinching line and impregnable solidity of the archers and foot-soldiers. These latter took a deeper interest in the result than the more showy performers, and were not carried away by the vanities of personal display.

Look at the year 1300, with the jubilee of Boniface going on. Look at 1400, with the death of Chaucer and Froissart, and the enthroning of Henry the Fourth, and what an amount of incident, of change and improvement, has been crowded into the space! The rise of national literatures, the softening of feudalism, the decline of Church power,—these—illustrated by Dante and Chaucer, by the alteration in the art of war, and above all, perhaps, by the translation of the Bible into the vulgar tongue—were not only the fruits gained for the present, but the promise of greater things to come. There will be occasional backslidings after this time, but the onward progress is steady and irresistible: the regressions are but the reflux waves in an advancing tide, caused by the very force and vitality of the great sea beyond. And after this view of some of the main features of the century, we shall take a very cursory glance at some of the principal events on which the portraiture is founded.

It is a bad sign of the early part of this period that our great landmarks are still battles and invasions. |A.D. 1314.|After Courtrai in 1302, where the nobility rushed blindfold into a natural ditch, we come upon Bannockburn in 1314, where Edward the Second, not comprehending the aim of his more politic father,—whose object was to counterpoise the growing power of the French monarchy by consolidating his influence at home,—had marched rather to revenge his outraged dignity than to establish his denied authority, and was signally defeated by Robert Bruce. Is it not possible that the stratagem by which the English chivalry suffered so much by means of the pits dug for their reception in the space in front of the Scottish lines was borrowed from Courtrai,—art supplying in that dry plain near Stirling what nature had furnished to the marshy Brabant? However this may be, the same fatal result ensued. Pennon and standard, waving plume and flashing sword, disappeared in those yawning gulfs, and at the present hour very rusty spurs and fragments of broken helmets are dug from beneath the soil to mark the greatness and the quality of the slaughter. Meantime, in compact phalanx—protected by the knights and gentlemen on the flanks, but left to its own free action—the Scottish array bore on. Strong spear and sharp sword did the rest, and the English army, shorn of its cavalry, disheartened by the loss of its leaders, and finally deserted by its pusillanimous king, retreated in confusion, and all hope of retaining the country by the right of conquest was forever laid aside. Poor Edward had, in appalling consciousness of his own imperfections, applied to the Pope for permission to rub himself with an ointment that would make him brave. Either the Pope refused his consent or the ointment failed of its purpose. Nothing could rouse a brave thought in the heart of the fallen Plantagenet. Sir Giles de Argentine might have been more effectual than all the unguents in the world. He led the king by the bridle till he saw him in a place of safety. He then stopped his horse and said, “It has never been my custom to fly, and here I must take my fortune.” Saying this, he put spurs to his horse, and, crying out, “An Argentine!” charged the squadron of Edward Bruce, and was borne down by the force of the Scottish spears. The fugitive king galloped in terror to the castle of Dunbar, and shipped off by sea to Berwick.

The next battle is so strongly corroborative of the failing supremacy of heavy armour, and the rising importance of the well-trained citizens, that it is worth mention, although at first sight it seems to controvert both these statements; for it was a fight in which certain courageous burghers were mercilessly exterminated by gorgeously-caparisoned knights. |A.D. 1328.|The townsmen of Bruges and Ypres had grown so proud and pugnacious that in 1328 they advanced to Cassel to do battle with the young King of France, Philip of Valois, at the head of all his chivalry. There was a vast amount of mutual contempt in the two armies. The leader of the bold Flemings, who was known as Little Jack, entered the enemy’s camp in disguise, and found young lords in splendid gowns proceeding from point to point, gossiping, visiting, and interchanging their invitations. Making his way back, he ordered a charge at once. The rush was nearly successful, and was only checked within a few yards of the royal tent. But the check was tremendous. The bloated burghers, filled with pride and gorged with wealth, had thought proper to ensconce their unwieldy persons in cuirasses as brilliant and embarrassing as the armour of the knights. The knights, however, were on horseback, and the embattled townsfolk were on foot. Great was the slaughter, useless the attempt to escape, and thirteen thousand were overborne and smothered. Ten thousand more were executed by some form of law, and the Bourgeoisie taught to rely for its safety on its agility and compactness, and not on “helm or hauberk’s twisted mail.”

The crop of battles grows rich and plentiful, for Edward the Third and Philip of Valois are rival kings and warriors, and may be taken as the representatives of the two states of society which were brought at this time face to face. For Edward, though as true a knight as Amadis himself in his own person, in policy was a favourer of the new ideas. When the war broke out, Philip behaved as if no change had taken place in the seat of power and the world had still continued divided between the lords and their armed retainers. He threw himself for support on the military service of his tenants and the aristocratic spirit of his nobles. Edward, wiser but less romantic, turned for assistance to the Commons of England,—bought over their good will and copious contributions by privileges granted to their trades,—invited skilled workmen over from Flanders, which, with the freest spirit in Europe, was under the least improved of the feudal governments,—and established woollen-works at York, fustian-works at Norwich, serges at Colchester, and kerseys in Devonshire. Mills were whirling round in all the counties, and ships coming in untaxed at every harbour. Fortunately, as is always the case in this country, it was seen that the success of one class of the people was beneficial to every other class. The baron got more rent for his land and better cloth for his apparel by the prosperity of his manufacturing neighbours. Money was voted readily in support of a king who entered into alliance with their best customers, the men of Ghent and Bruges; and at the head of all the levies which the parliament’s liberality enabled him to raise were the knights and gentlemen of England, totally freed now from any bias towards the French or prejudice against the Saxon; for they spoke the English tongue, dressed in English broadcloth, sang English ballads, and astonished the men of Gascony and Guienne with the vehemence of their unmistakably English oaths. Yet some of them held lands in feudal subjection to the French king. Flanders itself confessed the same sovereignty; and men of delicate consciences might feel uneasy if they lifted the sword against their liege lord. To soothe their scruples, James Van Arteveldt, the Brewer of Ghent, suggested to Edward the propriety of his assuming the title of King of France. The rebellious freeholders would then be in their duty in supporting their liege’s claims. So Edward, founding upon the birth of his mother, the daughter of the last King, Philip le Bel,—who was excluded by the Salic law, or at least by French custom, from the throne,—made claim to the crown of St. Louis, and transmitted the barren title to all his successors till the reign of George the Fourth. As if in right of his property on both sides of the Channel, Edward converted it into his exclusive domain. |A.D. 1340.|He so entirely exterminated the navy of France, and impressed that chivalrous nation with the danger of the seas by the victory of Helvoet Sluys, that for several centuries the command of the strait was left undisputed to England. Philip had endeavoured to obtain the mastery of it with a fleet of a hundred and fifty ships, mounted by forty thousand men. The Genoese had furnished an auxiliary squadron, and also a commander-in-chief, of the name of Barbavara. But the French admiral was a civilian of the name of Bahuchet, who thought the safest plan was the best, and kept his whole force huddled up in the commodious harbour. Edward collected a fleet of scarcely inferior strength, and fell upon the enemy as they lay within the port. It was in fact a fight on the land, for they ranged so close that they almost touched each other, and the gallant Bahuchet preserved himself from sea-sickness at the expense of all their lives. For the English archers made an incredible havoc on their crowded decks, and the pike-men boarded with irresistible power. Twenty thousand were slain in that fearful mêlée; and Edward, to show how sincere he was in his claim upon the throne of France, hanged the unfortunate Bahuchet as a traitor. The man deserved his fate as a coward: so we need not waste much sympathy on the manner of his death. This success with his ships was soon followed by the better-known victory of Crecy, 1346, and the capture of Calais. |A.D. 1356.|In ten years afterwards, the crowning triumph of Poictiers completed the destruction of the military power of France, by a slaughter nearly as great as that at Sluys and Crecy. In addition to the loss of lives in these three engagements, amounting to upwards of ninety thousand men, we are to consider the impoverishment of the country by the exorbitant ransoms claimed for the release of prisoners. John, the French king, was valued at three million crowns of gold,—an immense sum, which it would have exhausted the kingdom to raise; and, in addition to those destructive fights and crushing exactions, France was further weakened by the insurrection of the peasantry and the frightful massacres by which it was put down. If to these causes of weakness we add the depopulation produced by the unequalled pestilence, called the Plague of Florence, which spread all over the world, and in the space of a year carried off nearly a third of the inhabitants of Europe, we shall be justified in believing that France was reduced to the lowest condition she has ever reached, and that only the dotage of Edward, the death of the Black Prince, and the accession of a king like Richard II., saved that noble country from being, for a while at least, tributary and subordinate to her island-conqueror.

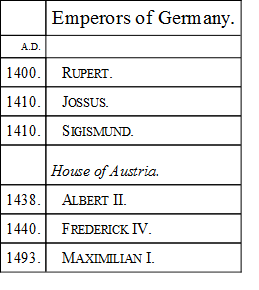

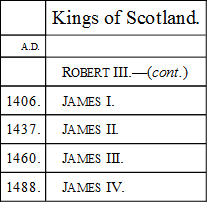

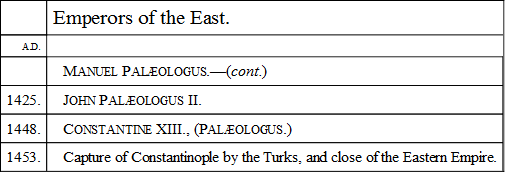

FIFTEENTH CENTURY

John Huss, (1370-1415,) Ximines

THE FIFTEENTH CENTURY

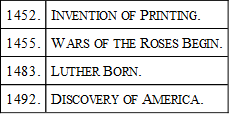

DECLINE OF FEUDALISM – AGINCOURT – JOAN OF ARC – THE PRINTING-PRESS – DISCOVERY OF AMERICAThe whole period from the twelfth to the fifteenth century has generally been considered so unvarying in its details, one century so like another, that it has been thought sufficient to class them all under the general name of the Middle Ages. Old Monteil, indeed, the author of “The French People of Various Conditions,” declines to individualize any age during that lengthened epoch, for “feudalism,” he says, “is as little capable of change as the castles with which it studded the land.” But a closer inspection does by no means justify this declaration. From time to time we have seen what great changes have taken place. The external walls of the baronial residence may continue the same, but vast alterations have occurred within. The rooms have got a more modern air; the moat has begun to be dried up, and turned into a bowling-green; the tilt-yard is occasionally converted into a garden; and, in short, in all the civilized countries of Europe the life of society has accumulated at the heart. Power is diffused from the courts of kings; and instead of the spirit of independence and opposition to the royal authority which characterized former centuries, we find the courtiers’ arts more prevalent now than the pride of local grandeur. The great vassals of the Crown are no longer the rivals of their nominal superior, but submissively receive his awards, or endeavour to obtain the sanction of his name to exactions which they would formerly have practised in their own. Monarchy, in fact, becomes the spirit of the age, and nobility sinks willingly into the subordinate rank. This itself was a great blow to the feudal system, for the essence of that organized society was equality among its members, united to subordination of conventional rank,—a strange and beautiful style of feeling between the highest and the lowest of that manly brotherhood, which made the simple chevalier equal to the king as touching their common knighthood,—of which we have at the present time the modernized form in the feeling which makes the loftiest in the land recognise an equal and a friend in the person of an untitled gentleman. But this latter was to be the result of the equalizing effect of education and character. In the fifteenth century, feudalism, represented by the great proprietors, was about to expire, as it had already perished in the decay of its armed and mailed representatives in the field of battle. By no lower hand than its own could the nobility be overthrown either in France or England. The accident of a feeble king in both countries was the occasion of an internecine struggle,—not, as it would have been in the tenth century, for the possession of the crown, but for the custody of the wearer of it. The insanity of Charles VI. almost exterminated the lords of France; the weakness of Henry VI. and the Wars of the Roses produced the same result in England. It seemed as if in both countries an epidemic madness had burst out among the nobility, which drove them to their destruction. Wildly contending with each other, neglecting and oppressing the common people, the lords and barons were unconscious of the silent advances of a power which was about to overshadow them all. And, as if to drive away from them the sympathy which their fathers had known how to excite among the lower classes by their kindness and protection, they seemed determined to obliterate every vestige of respect which might cling to their ancient possessions and historic names, by the most unheard-of cruelty and falsehood in their treatment of each other.