полная версия

полная версияThe Eighteen Christian Centuries

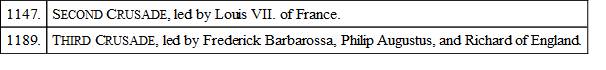

But in the following year a new detachment made their appearance in his states. This was the second ban, or crusade of the knights and barons. Better regulated in its military organization than the other, it presented the same astonishing scenes of debauchery and vice; and dividing, for the sake of sustenance, into four armies, and taking four different routes, they at length, in greatly-diminished numbers, but with unabated hope and energy, presented themselves before the walls of Constantinople. This was no mob like their famished and fainting predecessors. All the gallant lords of Europe were here, inspired by knightly courage and national rivalries to distinguish themselves in fight and council. Of these the best-known were Godfrey of Bouillon, Baldwyn of Flanders, Robert of Normandy, (William the Conqueror’s eldest son,) Hugh the Great, Count of Vermandois, and Raymond of St. Gilles. Six hundred thousand men had left their homes, with innumerable attendants—women, and jugglers, and servants, and workmen of all kinds. Tens of thousands perished by the way; others established themselves in the cities on their route to keep up the communication; and at last the Genoese and Pisan vessels conveyed to the Golden Horn the strength of all Europe, the hardy survivors of all the perils of that unexampled march—few indeed in number, but burning with zeal and bravery. Alexis lost no time in diverting their dangerous strength from his own realms. He let them loose upon Nicea, and when it yielded to their valour he had the cleverness to outwit the Christian warriors, and claimed the city as his possession. On pursuing their course, they found themselves, after a victory over the Turks at Dorylæum, in the great Plain of Phrygia. Hunger, thirst, the extremity of heat, and the difficulty of the march, brought confusion and dismay into their ranks. All the horses died. Knights and chevaliers were seen mounted on asses, and even upon oxen; and the baggage was packed upon goats, and not unfrequently on swine and dogs. Thirst was fatal to five hundred in a single day. Quarrels between the nationalities added to these calamities. Lorrains and Italians, the men of Normandy and of Provence, were at open feud. And yet, in spite of these drawbacks, the great procession advanced. Baldwyn and Tancred succeeded in getting possession of the town of Edessa, on the Euphrates, and opened a communication with the Christians of Armenia. |A.D. 1098.|The siege of Antioch was their next operation, and the luxuries of the soil and climate were more fatal to the Crusaders than want and pain had been. On the rich banks of the Orontes, and in the groves of Daphne, they lost the remains of discipline and self-command and gave themselves up to the wildest excesses. But with the winter their enjoyment came to an end. Their camp was flooded; they suffered the extremities of famine; and when there were no more horses and impure animals to eat, they satiated their hunger on the bodies of their slaughtered enemies. Help, however, was at hand, or they must have perished to the last man. Bohemund corrupted the fidelity of a renegade officer in Antioch, and, availing themselves of a dark and stormy night, they scaled the walls with ladders, and rushed into the devoted city, shouting the Crusaders’ war-cry:—“It is the will of God!” and Antioch became a Christian princedom. But not without difficulty was this new possession retained. The Turks, under the orders of Kerboga, surrounded it with two hundred thousand men. There was neither entrance nor exit possible, and the worst of their previous sufferings began to be renewed. But Heaven came to the rescue. A monk of the name of Peter Bartholomew dreamt that under the great altar of the church would be found the spear which pierced the Saviour on the cross. The precious weapon rewarded their toil in digging, and armed with this the Christian charge was irresistible, and the Turks were cut in pieces or dispersed. Instead of making straight for Jerusalem, they lingered six months longer in Antioch, suffering from plague and the fatigues they had undergone. When at last the forward order was given, a remnant, consisting of fifty thousand men out of all the original force, began the march. As they got nearer the object of their search, and recognised the places commemorated in Holy Writ, their enthusiasm knew no bounds. The last elevation was at length surmounted, and Jerusalem lay in full view. “O blessed Jesus,” cries a monk who was present, “when thy Holy City was seen, what tears fell from our eyes!” Loud shouts were raised of “Jerusalem! Jerusalem! God wills it! God wills it!” They stretched out their hands, fell upon their knees, and embraced the consecrated ground. But Jerusalem was yet in the hands of the Saracens, and the sword must open their way into its sacred bounds. The governor had offered to admit the pilgrims within the walls, but in their peaceful dress and merely as visitors. This they refused, and determined to wrest it from its unbelieving lords. On the 15th of July, 1099, they found that their situation was no longer tenable, and that they must conquer or give up the siege. The brook Kedron was dried up, the sun poured upon them with unendurable heat, their provisions were exhausted, and in agonies of despair as well as of military ardour they gave the final assault. The struggle was long and doubtful. At length the Crusaders triumphed. Tancred and Godfrey were the first to leap into the devoted town. Their soldiers followed, and filled every street with slaughter. The Mosque of Omar was vigorously defended, and an indiscriminate massacre of Mussulmans and Jews filled the whole place with blood. In the mosque itself the stream of gore was up to the saddle-girths of a horse. The onslaught was occasionally suspended for a while, to allow the pious conquerors to go barefoot and unarmed to kneel at the Holy Sepulchre; and, this act of worship done, they returned to their ruthless occupation, and continued the work of extermination for a whole week. The depopulated and reeking town was added to the domains of Christendom, and the kingdom of Jerusalem was offered to Godfrey of Bouillon. With a modesty befitting the most Christian and noble-hearted of the Crusaders, Godfrey contented himself with the humbler name of Baron of the Holy Sepulchre; and with three hundred knights—which were all that remained to him when that crowning victory had set the other survivors at liberty to revisit their native lands—he established a standing garrison in the captured city, and anxiously awaited reinforcements from the warlike spirits they had left at home.

TWELFTH CENTURY

Bernard, (1091-1153,) Becket, (1119-1170,) Eustathius, Theodorus, Balsamon, Peter Lombard, William of Malmesbury, (1096-1143.)

THE TWELFTH CENTURY

ELEVATION OF LEARNING – POWER OF THE CHURCH – THOMAS À-BECKETTThe effect of the first Crusade had been so prodigious that Europe was forced to pause to recover from its exhaustion. More than half a million had left their homes in 1095; ten thousand are supposed to have returned; three hundred were left with Godfrey in the Christian city of Jerusalem; and what had become of all the rest? Their bones were whitening all the roads that led to the Holy Land; small parties of them must have settled in despair or weariness in towns and villages on their way; many were sold into slavery by the rapacity of the feudal lords whose lands they traversed; and when the madness of the time had originated a Crusade of Children, and ninety thousand boys of ten or twelve years of age had commenced their journey, singing hymns and anthems, and hoping to conquer the infidels with the spiritual arms of innocence and prayer, the whole band melted away before they reached the coast. Barons, and counts, and bishops, and dukes, all swooped down upon the devoted march, and before many weeks’ journeying was achieved the Crusade was brought to a close. Most of the children had died of fatigue or starvation, and the survivors had been seized as legitimate prey and sold as slaves.

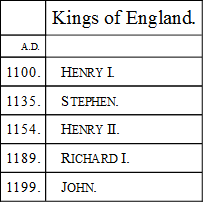

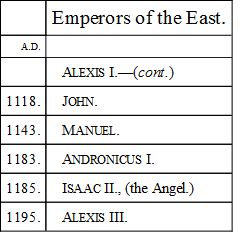

Meantime the brave and heroic Godfrey—the true hero of the expedition, for he elevated the ordinary virtues of knighthood and feudalism into the nobler feelings of generosity and romance—gained the object of his earthly ambition. Having prayed at the sepulchre, and cleansed the temple from the pollution of the unbelievers’ presence, wearied with all his labours, and feeling that his task was done, he sank into deep despondency and died. |A.D. 1100.|Volunteers in small numbers had occasionally gone eastward to support the Cross Ambition, thoughtlessness, guilt, and fanaticism sent their representatives to aid the conqueror of Judea; and his successors found themselves strong enough to bid defiance to the Turkish power. They carried all their Western ideas along with them. They had their feudal holdings and knightly quarrels. The most venerated names in Holy Writ were desecrated by unseemly disputes or the most frivolous associations. The combination, indeed, of their native habits and their new acquisitions might have moved them to laughter, if the men of the twelfth century had been awake to the ridiculous. There was a Prince of Galilee, a Marquis of Joppa, a Baron of Sidon, a Marquis of Tyre. Our own generation has renewed the strange juxtaposition of the East and West by the language employed in steamboats and railways. Trains will soon cross the Desert with warning whistles and loud jets of steam and all the phraseology of an English line. For many years the waters of the mysterious Red Sea have been dashed into foam by paddles made in Liverpool or Glasgow. But these are visitors of a very different kind from Bohemund and Baldwyn. Baldwyn, indeed, seemed less inclined than his companions to carry his European training to its full extent. He Orientalized himself in a small way, perhaps in imitation of Alexander the Great, and, dressed in the long flowing robes of the country, he made his attendants serve him with prostrations, and almost with worship. He married a daughter of the land, and in other respects endeavoured to ingratiate himself with the Saracens by treating them with kindness and consideration. The bravery of those warriors of the Desert endeared them to the rough-handed barons of the West. It was impossible to believe that men with that one pre-eminent virtue could be so utterly hateful as they had been represented; and when the intercourse between the races became more unrestrained, even the religious asperities of the Crusaders became mitigated, they found so many points of resemblance between their faiths. There was not an honour which the Christian paid to the Virgin which was not yielded by the Mohammedan to Fatima. All the doctrines of the Christian creed found their counterparts in the professions of the followers of the Law. Allah was an incarnation of the Deity; and even the mystery of the Trinity was not indistinctly seen in the legend of the three rays which darted from the idea of Mohammed in the mind of the Creator. While this community of sentiment softened the animosity of the crusading leaders towards their enemies, a still greater community of suffering and danger softened their feelings towards their followers and retainers. In that scarcity of knights and barons, the value of a serf’s arm or a mechanic’s skill was gratefully acknowledged. There had been many mutual kindnesses between the two classes all through those tedious and blood-stained journeys and desperate fights. A peasant had brought water to a wounded lord when he lay fainting on the burning soil; a workman had had the revelation of the true crown: they were no longer the property and slaves of the noble, who considered them beings of a different blood, but fellow-soldiers, fellow-sufferers, fellow-Christians. They were not spoken of in the insulting language of the West, and called “our thralls,” “our slaves,” “our bondsmen;” at the worst they were called “our poor,” and lifted by that word into the quality of brothers and men. The precepts of the gospel in favour of the humble and suffering were felt for the first time to have an application to the men who had toiled on their lands and laboured in their workshops, but who were now their support in the shock of battle, and companions when the victory was won. Only they were poor; they had no lands; they had no arms upon their shields. So Baldwyn gave them large tracts of country; and they became vassals and feudatories for fertile fields near Jericho and rich farms on the Jordan. They were gentlemen by the strength of their own right hands, as the fathers of their lords and suzerains had been.

But the amalgamation of race and condition was not carried on in the East more surely or more extensively than in the West. The expenses of preparing for the pilgrimage had impoverished the richest of the lords of the soil. They had been forced to borrow money and to mortgage their estates to the burghers of the great commercial towns, which, quietly and unobserved, had spread themselves in many parts of France and Italy. Genoa had already attained such a height of prosperity that she could furnish vessels for the conveyance of half the army of the Crusade. In return for her cargoes of knights and fighting-men, she brought back the wealth of the East,—silks, and precious stones, and spices, and vessels of gold and silver. The necessities of the time made the money-holder powerful, and the men who swung the hammer, and shaped the sword, and embroidered the banner, and wove the tapestry, indispensable. And what hold, except kindness, and privilege, and grants of land, had the baron on the skilful smith or the ingenious weaver who could carry his skill and energy wherever he chose? Besides, the multitudes who had been carried away from the pursuits of industry to fall at the siege of Antioch or perish by thirst in the Desert had given a greatly-increased value to their fellow-labourers left at home. While the castle became deserted, and all the pomp of feudalism retreated from its crumbling walls, the village which had grown in safety under its protection flourished as much as ever—flourished, indeed, so much that it rapidly became a town, and boasted of rich citizens who could help to pay off their suzerain’s encumbrances and present him with an offering on his return. The impoverished and grateful noble could do no less, in gratitude for gift and contribution, than secure them in the enjoyment of greater franchises and privileges than they had possessed before. The Church also gained by the diminished number and power of the lords, who had seized upon tithe and offering and had looked with disdain and hostility on the aggressions of the lower clergy. True to its origin, the Church still continued the leader of the people, in opposition to the pretensions of the feudal chiefs. It was still a democratic organization for the protection of the weak against the powerful; and though we have seen that the bishops and other dignitaries frequently assumed the state and practised the cruelties of the grasping and illiterate baron, public opinion, especially in the North of Europe, was not revolted against these instances of priestly domination, for whatever was gained by the crozier was lost to the sword. It was even a consolation to the injured serf to see the truculent landlord who had oppressed him oppressed in his turn by a still more truculent bishop, especially when that bishop had sprung from the dregs of the people, and—crown and consummation of all—when the Pope, God’s vicegerent upon earth, who dethroned emperors and made kings hold his stirrup as he mounted his mule, was descended from no more distinguished a family than himself. It was the effort of the Church, therefore, in all this century, to lower the noble and to elevate the poor. To gain popularity, all arts were resorted to. The clergy were the showmen and play-actors of the time. The only amusement the labourer could aim at was found for him, in rich processions and gorgeous ceremony, by the priest. How could any fault of the abbot or prelate turn away the affection of the peasant from the Church, which was in a peculiar manner his own establishment? Never had the drunkenness, the debauchery and personal indulgences of the upper ecclesiastics reached such a pitch before. The gluttony of friars and monks became proverbial. The community of certain monasteries complained of the austerity of their abbots in reducing their ordinary dinners from sixteen dishes to thirteen. The great St. Bernard describes many of the rulers of the Church as keeping sixty horses in their stables, and having so many wines upon their board that it was impossible to taste one-half of them. Yet nothing shook the attachment of the uneducated commons. Their priest got up dances and concerts and miracles for their edification, and had a right to enjoy all the luxuries of life. Once freed, therefore, from the watchful enmity of lord and king, the Church was well aware that its power would be irresistible. The people were devoted to it as their earthly defender against their earthly oppressors, the caterer of all their amusements, and as their guide in the path to heaven. Gratitude and credulity, therefore, were equally engaged in its behalf. And new influences came to its support. Romance and wonder gathered round the champions of the Faith fighting in the distant regions of the East. Every thing became magnified when seen through the medium of ignorance and fanaticism. The tales, therefore, strange enough in themselves, which were related by pilgrims returning from the Holy Land, and amplified a hundredfold by the natural exaggeration of the vulgar, raised higher than ever the glory of the Church. The fastings and self-inflicted scourgings of holy men, it was believed, effected more than the courage of Godfrey or Bohemund; and even of Godfrey it was said that his ascetic life and painful penances caused more losses to the enemy than his matchless strength and military skill.

It would be delightful if we could place ourselves in the position of the breathless crowds at that time listening for the news from Palestine. No telegraphic despatch from the Crimea or Hindostan was ever waited for with such impatience or received with such emotion. The baron summoned the palmer into his hall, and heard the strange history of the march to Jerusalem, and the crowning of a Christian king, and the creation of a feudal court, with a pang, perhaps, of regret that he had not joined the pilgrimage, which might have made him Duke of Bethlehem or monarch of Tiberias. But the peasants in their workshops, or the whole village assembled in the long aisles of their church, lent far more attentive ears to the wayfaring monk who had escaped from the prison of the Saracen, and told them of the marvels accomplished by the bones of martyrs and apostles which had been revealed to holy pilgrims in their dream on the Mount of Olives. Footprints on the heights of Calvary, and portions of the manger in Bethlehem, were described in awe-struck voice; and when it was announced that in the belt of the narrator, enwrapped in a silken scarf,—itself a fabric of incalculable worth,—was a hair of an apostle’s head, (which their lord had purchased for a large sum,) to be deposited upon their altar, they must have thought the sacrifices and losses of the Crusade amply repaid. And no amount of these sacred articles seemed in the least to diminish their importance. The demand was always greatly in advance of the supply, however vast it might be. And as the mines of California and Australia have hitherto deceived the prophets of evil, by having no perceptible effect on the price of the precious metals, the incalculable importation of saints’ teeth, and holy personages’ clothes, and fragments of the true Cross, and prickles of the real Crown of Thorns, had no depressing effect on the market-value of similar commodities with which all Christian Europe was inundated. Faith seemed to expand in proportion as relics became plentiful, as credit expands on the security of a supply of gold. And as many of those articles were actually of as clearly-recognised a pecuniary value as houses or lands, and represented in any market or banking-house a definite and very considerable sum, it is not too much to say that the capital of the West was greatly increased by these acquisitions from the East. The cup of onyx, carved in one stone, which was believed to have been that in which the wine of the Last Supper was held when our Saviour instituted the Communion, was pledged by its owner for an enormous sum, and—what is perhaps more strange—was redeemed when the term of the loan expired by the repayment of principal and interest. The intercourse, therefore, between power and money showed that each was indispensable to the other. The baron relaxed his severity, and the citizen opened his purse-strings; the Church inculcated the equality of all men in presence of the altar; and when the kings perceived what merchandise might be made of privileges and exemptions accorded to their subjects, and how at one great blow the townsman’s squeezable riches would be increased and the baron’s local influence diminished, there was a struggle between all the crowned heads as to which should be most favourable to the commons. It was in this century, owing to the Crusades, which made the commonalty indispensable and the nobility weak, which strengthened the Crown and the Church and made it their joint interest to restrain the exactions of the feudal proprietors, that the liberties of Europe took their rise in the establishment of the third estate. In the county of Flanders, the great towns had already made themselves so wealthy and independent that it scarcely needed a legal ratification of their franchise to make them free cities. But in Italy a step further had been made, and the great word Republic, which had been silent for so many years, had again been heard, and had taken possession of the general mind. In spite of the opposition and the military successes of Roger, the Norman king of Sicily, the spirit which animated those great trading communities was never subdued. In Venice itself—the greatest and most illustrious of those republics, the first founded and last overthrown—the original municipal form of government had never been abolished. At all times its liberties had been preserved and its laws administered by officers of its own choice, and from it proceeded at this time a feeling of social equality and an example of commercial prosperity which had a strong effect on the nascent freedom of the lower and industrious classes over all the world. Genoa was not inferior either in liberty or enterprise to any of its rivals. Its fleets traversed the Mediterranean, and, being equally ready to fight or to trade, brought wealth and glory home from the coasts of Greece and Asia. It is to be observed that the first reappearance of self-government was presented in the towns upon the coast, whose situation enabled them to compensate for smallness of territory by the command of the sea. The shores of Italy and the south of France, and the indented sea-line of Flanders, followed in this respect the example set in former ages by Greece, and Tyre, and Pentapolis, and Carthage. There can be no doubt that the sight of these powerful communities, governed by their consuls and legislated for by their parliamentary assemblies, must have put new thoughts into the heads of the serfs and labourers returning, in vessels furnished by citizens like themselves, from the conquest of Cyprus and Jerusalem, where the whole harvest of wealth and glory had been reaped by their lords. Encouraged by these examples, and by the protection of the King of France and Emperor of Germany, the towns in Central and Western Europe exerted themselves to emulate the republican cities of the South. The nearest approach they could hope to the independence they had seen in Pisa or Venice was the possession of the right of electing their own magistrates and making their own laws. These privileges, we have seen, were insured to them by the helplessness and impoverishment of the feudal aristocracy and the countenance of the Church.