полная версия

полная версияThe Eighteen Christian Centuries

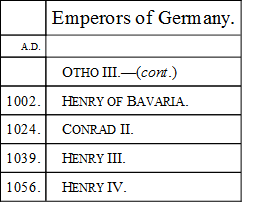

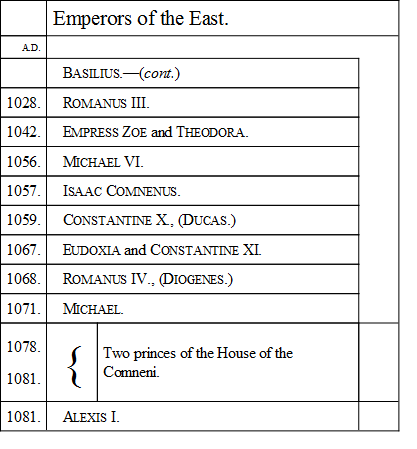

With the nobles he proceeded in a different manner. His task, you will remember, was to regain the universal submission of the nation; and success at first seemed almost hopeless, for his real power, like that of the weakest of his immediate predecessors, extended no further than his personal holdings. In his fiefs of France proper (the small district including Paris) and Burgundy he was all-powerful; but in the other principalities and dukedoms he was looked on merely as a neighbouring potentate with some shadowy claims of suzerainty, with no right of interference in their internal administration. The other feudatories under the old monarchy, but who were in reality independent sovereigns under the new, were the Dukes of Normandy and Flanders, and Aquitaine and Toulouse. These made the six lay peerages of the kingdom, and, with the six ecclesiastical chief rulers, made the Twelve Peers of France. Of the lay peerages it will be seen that Hugh was in possession of two—the best situated and most populous of all. The extent of his possessions and the influence of his name were excellent starting-points in his efforts to restore the power of the Crown; but other things were required, and the first thing he aimed at was to place his newly-acquired dignity on the same vantage-ground of hereditary succession as his dukedoms had long been. |A.D. 989.|With great pomp and solemnity he himself was anointed with the holy oil by the hands of the Pope; and he took advantage of the self-satisfied security of the other nobles to have the ceremony of a coronation performed on his son during his lifetime, and by this arrangement the appearance of election was avoided at his death. Its due weight must be given to the universal superstition of the time, when we attribute such importance to the formal consecration of a king. Externals, in that age, were all in all. Something mystic and divine, as we have said before, was supposed to reside in the very fact of having the crown placed on the head with the sanction and prayers of the Church. Opposition to the wearer became not only treason, but impiety; and when the same policy was pursued by many generations of Hugh’s successors, in always procuring the coronation of their heirs before their demise, and thus obliterating the remembrance of the elective process to which they owed their position, the royal power had the vast advantage of hereditary descent added to its unsubstantial but never-abandoned claim of paramount authority. The effects of this momentous change in the dynasty of one of the great European nations were felt in all succeeding centuries. The family connection between the house of France and the Empire was dissolved; and the struggle between the old condition of society and the rising intelligence of the peoples—which is the great characteristic of the Middle Ages—took a more defined form than before: aristocracy assumed its perfected shape of king and nobility combined for mutual defence on one side, and on the other the towns and great masses of the nations striving for freedom and privilege under the leadership of the sympathizing and democratic Church; for the Church was essentially democratic, in spite of the arrogance and grasping spirit of some of its principal leaders. From hereditary aristocracy and hereditary royalty it was equally excluded; and the celibacy of the clergy has had this good effect, if no other: Its members were recruited from the people, and derived all their influence from popular support. In Germany the same process was going on, though without the crowning consummation of making the empire non-elective. |A.D. 962.|Otho, however—worthier of the name of Great than many who have borne that ambitious title—succeeded in limiting that highest of European dignities to the possessors of the German crown, and commenced the connection between Upper Italy and the Emperors which still subsists (so uneasily for both parties) under the house of Austria.

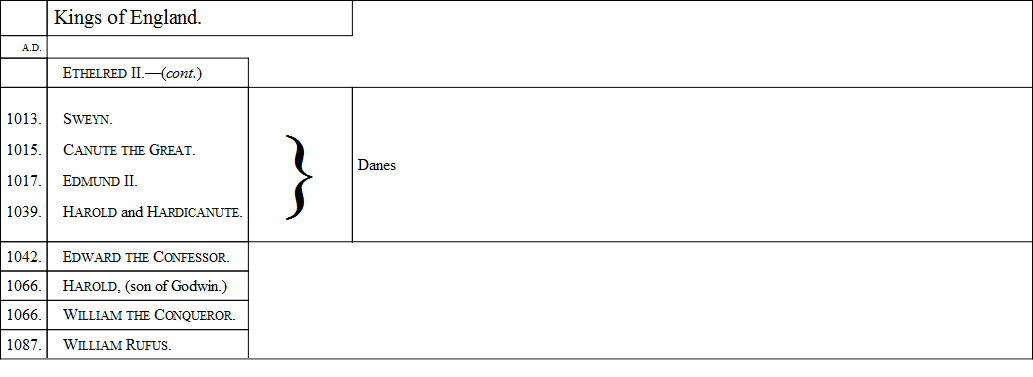

In England the misery of the population had reached its maximum. The immigration of the Norsemen had been succeeded by numberless invasions, accompanied with all the horrors of barbarism and religious hatred; for the Danes who devastated the shores in this age were as remorselessly savage, and as bitterly heathen, as their predecessors a hundred years before. No place was safe for the unhappy Christianized Saxons. Their sufferings were of the same kind as those of the inhabitants of Normandy when Rollo began his ravages. Their priest-ridden kings and impoverished nobles could give them no protection. Bribes were paid to the assailants, and only brought over increasing and hungrier hordes. The land was a prey to wretchedness of every kind, and it was slender consolation to the starving and trampled multitudes that all the world was suffering to almost the same extent. Saracens were devastating the coasts of Italy, and a wild tribe of Sclaves trying to burst through the Hungarian frontier. At Rome itself, the capital of intellect and religion, such iniquities were perpetrated on every side that Protestant authors themselves consent to draw a veil over them for the sake of human nature; and in those sketches we require to do nothing more than allude to the crimes and wickedness of the papal court as one of the features by which the century was marked. Women of high rank and infamous character placed the companions of their vices in the highest offices of the Church, and seated their sons or paramours on the papal throne. Spiritual pretensions rose almost in proportion to personal immorality, and the curious spectacle was presented of a power losing all respect at home by conduct which the heathen emperors of the first century scarcely equalled; of popes alternately dethroning and imprisoning each other—sometimes of two popes at a time—always dependent for life or influence on the will of the emperor, or whoever else might be dominant in Italy—and yet successfully claiming the submission and reverence of distant nations as “Bishop of all the world” and lineal “successors of the Prince of the Apostles.” This claim had never been expressly made before, and is perhaps the most conclusive proof of the darkness and ignorance of this period. Men were too besotted to observe the incongruity between the life and profession of those blemishes of the Church, even when by travelling to the seat of government they had the opportunity of seeing the Roman pontiff and his satellites and patrons. The rest of the world had no means of learning the real state of affairs. Education had almost died out among the clergy themselves. Nobody else could write or read. Travelling monks gave perverted versions, we may believe, of every thing likely to be injurious to the interests of the Church; and the result was, that everywhere beyond the city-walls the thunder of a Boniface the Seventh, or a John the Twelfth, was considered as good thunder as if it had issued from the virtuous indignation of St. Paul.

But just as this century drew to a close, various circumstances concurred to produce a change in men’s minds. It was a universally-diffused belief that the world would come to an end when a thousand years from the Saviour’s birth were expired. The year 999 was therefore looked upon as the last which any one would see. And if ever signs of approaching dissolution were shown in heaven and earth, the people of this century might be pardoned for believing that they were made visible to them. Even the breaking up of morals and law, and the wide deluge of sin which overspread all lands, might be taken as a token that mankind were deemed unfit to occupy the earth any more. In addition to these appalling symptoms, famines were renewed from year to year in still increasing intensity and brought plague and pestilence in their train. The land was left untilled, the house unrepaired, the right unvindicated; for who could take the useless trouble of ploughing or building, or quarrelling about a property, when so few months were to put an end to all terrestrial interests? Yet even for the few remaining days the multitudes must be fed. Robbers frequented every road, entered even into walled towns; and there was no authority left to protect the weak, or bring the wrong-doer to punishment. Corn and cattle were at length exhausted; and in a great part of the Continent the most frightful extremities were endured; and when endurance could go no further, the last desperate expedient was resorted to, and human flesh was commonly consumed. One man went so far as to expose it for sale in a populous market-town. The horror of this open confession of their needs was so great, that the man was burned, but more for the publicity of his conduct than for its inherent guilt. Despair gave a loose to all the passions. Nothing was sacred—nothing safe. Even when food might have been had, the vitiated taste made bravado of its depravation, and women and children were killed and roasted in the madness of the universal fear. Meantime the gentler natures were driven to the wildest excesses of fanaticism to find a retreat from the impending judgment. Kings and emperors begged at monastery-doors to be admitted brethren of the Order. Henry of Germany and Robert of France were saints according to the notions of the time, and even now deserve the respect of mankind for the simplicity and benevolence of their characters. Henry the Emperor succeeded in being admitted as a monk, and swore obedience on the hands of the gentle abbot who had failed in turning him from his purpose. “Sire,” he said at last, “since you are under my orders, and have sworn to obey me, I command you to go forth and fulfil the duties of the state to which God has called you. Go forth, a monk of the Abbey of St. Vanne, but Emperor of the West.” Robert of France, the son of Hugh Capet, placed himself, robed and crowned, among the choristers of St. Denis, and led the musicians in singing hymns and psalms of his own composition. Lower men were satisfied with sacrificing the marks of their knightly and seignorial rank, and placed baldrics and swords on the altars and before the images of saints. Some manumitted their serfs, and bestowed large sums upon charitable trusts, commencing their disposition with words implying the approaching end of all. Crowds of the common people would sleep nowhere but in the porches, or at any rate within the shadow, of the churches and other holy buildings; and as the day of doom drew nearer and nearer, greater efforts were made to appease the wrath of Heaven. Peace was proclaimed between all classes of men. From Wednesday night till Monday evening of each week there was to be no violence or enmity or war in all the land. It was to be a Truce of God; and at last, all their strivings after a better state, acknowledgments of a depraved condition, and heartfelt longings for something better, purer, nobler, received their consummation, when, in the place of the unprincipled men who had disgraced Christianity by carrying vice and incredulity into the papal chair, there was appointed to the highest of ecclesiastical dignities a man worthy of his exaltation; and the good and holy Gerbert, the tutor, guide, and friend of Robert of France, was appointed Pope in 998, and took the name of Sylvester the Second.

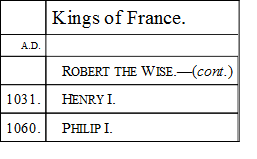

ELEVENTH CENTURY

Anselm, (1003-1079,) Abelard, (1079-1142,) Berengarius, Roscelin, Lanfranc, Theophylact, (1077.)

THE ELEVENTH CENTURY

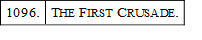

THE COMMENCEMENT OF IMPROVEMENT – GREGORY THE SEVENTH – FIRST CRUSADEAnd now came the dreaded or hoped-for year. The awful Thousand had at last commenced, and men held their breath to watch what would be the result of its arrival. “And he laid hold of the dragon, that old serpent, which is the Devil, and Satan, and bound him for a thousand years, and cast him into the bottomless pit, and shut him up, and set a seal upon him, that he should deceive the nations no more, till the thousand years should be fulfilled: and after that he must be loosed a little season.” (Revelation xx. 2, 3.) With this text all the pulpits in Christendom had been ringing for a whole generation. And not the pulpits only, but the refection-halls of convents, and the cottages of the starving peasantry. Into the castle also of the noble, we have seen, it had penetrated; and the most abject terror pervaded the superstitious, while despair, as in shipwrecked vessels, displayed itself amid the masses of the population in rioting and insubordination. The spirit of evil for a little season was to be let loose upon a sinful world; and when the observer looked round at the real condition of the people in all parts of Europe—at the ignorance and degradation of the multitude, the cruelty of the lords, and the unchristian ambition and unrestrained passions of the clergy—it must have puzzled him how to imagine a worse state of things even when the chain was loosened from “that old serpent,” and the world placed unresistingly in his folds. Yet, as if men’s minds had now reached their lowest point, there was a perpetual rise from the beginning of this date. When the first day of the thousand-and-first year shone upon the world, it seemed that in all nations the torpor of the past was to be thrown off. There were strivings everywhere after a new order of things. Coming events cast their shadows a long way before; for in the very beginning of this century, when it was reported that Jerusalem had been taken by the Saracens, Sylvester uttered the memorable words, “Soldiers of Christ, arise and fight for Zion.” By a combination of all Christian powers for one object, he no doubt hoped to put an end to the party quarrels by which Europe was torn in pieces. And this great thought must have been germinating in the popular heart ever since the speech was spoken; for we shall see at the end of the period we are describing how instantaneously the cry for a crusade was responded to in all lands. In the mean time, the first joy of their deliverance from the expected destruction impelled all classes of society in a more honourable and useful path than they had ever hitherto trod. As if by universal consent, the first attention was paid to the maintenance of the churches, those holy buildings by whose virtues the wrath of Heaven had been turned away. In France, and Italy, and Germany, the fabrics had in many places been allowed to fall into ruin. They were now renovated and ornamented with the costliest materials, and with an architectural skill which, if it previously existed, had had no room for its display. Stately cathedrals took the place of the humble buildings in which the services had been conducted before. Every thing was projected on a gigantic scale, with the idea of permanence prominently brought forward, now that the threatened end of all things was seen to be postponed. The foundations were broad and deep, the walls of immense thickness, roofs steep and high to keep off the rain and snow, and square buttressed towers to sustain the church and furnish it at the same time with military defence. It was a holy occupation, and the clergy took a prominent part in the new movement. Bishops and monks were the principal members of a confraternity who devoted themselves to the science of architecture and founded all their works on the exact rules of symmetry and fitness. Artists from Italy, where Roman models were everywhere seen, and enthusiastic students from the south of France, where the great works of the Empire must have exercised an ennobling influence on their taste and fancy, brought their tribute of memory or invention to the design. Tall pillars supported the elevated vault, instead of the flat roof of former days; and gradually an approach was made to what, in after-periods, was recognised as the pure Gothic. Here, then, was at last a real science, the offspring of the highest aspirations of the human mind. Churches rising in rich profusion in all parts of the country were the centres of architectural taste. The castle of the noble was no longer to be a mere mass of stones huddled on each other, to protect its inmates from outward attack. The skill of the learned builder was called in, and on picturesque heights, safe from hostile assault by the difficulty of approach, rose turret and bartizan, arched gateway and square-flanked towers, to add new features to the landscape, and help the march of civilization, by showing to that allegorizing age the result, both for strength and beauty, of regularity and proportion. For at this time allegory, which gave an inner meaning to outward things, was in full force. There was no portion of the parish church which had not its mystical significance; and no doubt, at the end of this century, the architectural meaning of the external alteration of the structure was perceived, when the great square tower, which typified resistance to worldly aggression, was exchanged for the tall and graceful spire which pointed encouragingly to heaven. Occasions were eagerly sought for to give employment to the ruling passion. Building went on in all quarters. The beginning of this century found eleven hundred and eight monasteries in France alone. In the course of a few years she was put in possession of three hundred and twenty-six more. |A.D. 1035.|The magnificent Abbey of Fontenelle was restored in 1035 by William of Normandy; and this same William, whom we shall afterwards see in the somewhat different character of Conqueror and devastator of England, was the founder and patron of more abbeys and monasteries than any other man. Many of them are still erect, to attest the solidity of his work; the ruins of the others raise our surprise that they are not yet entire—so vast in their extent and gigantic in their materials. But the same character of permanence extended to all the works of this great builder’s[2] hands—the systems of government no less than the fabrics of churches. The remains of his feudalism in our country, no less than the fragments of his masonry at Bayeux, Fecamp, and St. Michael’s, attest the cyclopean scale on which his superstructures were reared. Nor were these great architectural efforts which characterize this period made only on behalf of the clergy. It gives a very narrow notion, as Michelet has observed, of the uses and purposes of those enormous buildings, to view them merely as places for public worship and the other offices of religion. The church in a district was, in those days, what a hundred other buildings are required to make up in the present. It was the town-hall, the market-place, the concert-room, the theatre, the school, the news-room, and the vestry, all in one. We are to remember that poverty was almost universal. The cottages in which the serfs and even the freemen resided were wretched hovels. They had no windows, they were damp and airless, and were merely considered the human kennels into which the peasantry retired to sleep. In contrast to this miserable den there arose a building vast and beautiful, consecrated by religion, ornamented with carving and colour, large enough to enable the whole population to wander in its aisles, with darker recesses under the shade of pillars, to give opportunity for familiar conversation or the enjoyment of the family meal. The church was the poor man’s palace, where he felt that all the building belonged to him and was erected for his use. It was also his castle, where no enemy could reach him, and the love and pride which filled his heart in contemplating the massive proportions and splendid elevation of the glorious fane overflowed towards the officers of the church. The priest became glorified in his eyes as the officiating servant in that greatest of earthly buildings, and the bishop far outshone the dignity of kings when it was known that he had plenary authority over many such majestic fabrics. Ascending from the known to the unknown, the Pope of Rome, the Bishop of Bishops, shone upon the bewildered mind of the peasant with a light reflected from the object round which all his veneration had gathered from his earliest days—the scene of all the incidents of his life—the hallowed sanctuary into which he had been admitted as an infant, and whose vaults should echo to the funeral service when he should have died.

But this century was distinguished for an upheaving of the human mind, which found its development in other things besides the bursting forth of architectural skill. It seemed that the chance of continued endurance, vouchsafed to mankind by the rising of the sun on the first morning of the eleventh century, gave an impulse to long-pent-up thoughts in all the directions of inquiry. The dulness of unquestioning undiscriminating belief was disturbed by the freshening breezes of dissidence and discussion. The Pope himself, the venerable Sylvester the Second, had acquired all the wisdom of the Arabians by attending the Mohammedan schools in the royal city of Cordova. There he had learned the mysteries of the secret sciences, and the more useful knowledge—which he imported into the Christian world—of the Arabic numerals. The Saracenic barbarism had long yielded to the blandishments of the climate and soil of Spain; and emirs and sultans, in their splendid gardens on the Guadalquivir, had been discussing the most abstruse or subtle points of philosophy while the professed teachers of Christendom were sunk in the depths of ignorance and credulity. Sylvester had made such progress in the unlawful learning accessible at the head-quarters of the unbelievers, that his simple contemporaries could only account for it by supposing he had sold himself to the enemy of mankind in exchange for such prodigious information. He was accused of the unholy arts of magic and necromancy; and all that orthodoxy could do to assert her superiority over such acquirements was to spread the report, which was very generally credited, that when the years of the compact were expired, the paltering fiend appeared in person and carried off his debtor from the midst of the affrighted congregation, after a severe logical discussion, in which the father of lies had the best of the argument. This was a conclusive proof of the danger of all logical acquirements. But as time passed on, and the darkness of the tenth century was more and more left behind, there arose a race of men who were not terrified by the fate of the philosophic Sylvester from cultivating their understandings to the highest pitch. Among those there were two who particularly left their marks on the genius of the time, and who had the strange fortune also of succeeding each other as Archbishops of Canterbury. These were Lanfranc and Anselm. |A.D. 1042.|When Lanfranc was still a monk at Caen, he had attracted to his prelections more than four thousand scholars; and Anselm, while in the same humble rank, raised the schools of Bec in Normandy to a great reputation. From these two men, both Italians by birth, the Scholastic Philosophy took its rise. The old unreasoning assent to the doctrines of Christianity had now new life breathed into it by the permitted application of intellect and reason to the support of truth. In the darkness and misery of the previous century, the deep and mysterious dogma of Transubstantiation had made its first authoritative appearance in the Church. Acquiesced in by the docile multitude, and accepted by the enthusiastic and imaginative as an inexpressible gift of fresh grace to mankind, and a fitting crown and consummation of the daily-recurring miracles with which the Mother and Witness of the truth proved and maintained her mission, it had been attacked by Berenger of Tours, who used all the resources of reason and ingenuity to demonstrate its unsoundness. |A.D. 1059.|But Lanfranc came to the rescue, and by the exercise of a more vigorous dialectic, and the support of the great majority of the clergy, confuted all that Berenger advanced, had him stripped of his archdeaconry of Angers and other preferments, and left him in such destitution and disfavour that the discomfited opponent of the Real Presence was forced to read his retractation at Rome, and only expiated the enormity of his fault by the rigorous seclusion of the remainder of his life. The hopeful feature in this discussion was, that though the influence of ecclesiastic power was not left dormant, in the shape of temporal ruin and spiritual threats, the exercise of those usual weapons of authority was accompanied with attempts at argument and conviction. Lanfranc, indeed, in the very writings in which he used his talents to confute the heretic, made such use of his reasoning and inductive faculties that he nearly fell under the ban of heresy himself. He had the boldness to imagine a man left to the exercise of his natural powers alone, and bringing observation, argument, and ratiocination to the discovery of the Christian dogmas; but he was glad to purchase his complete rehabilitation, as champion of the Church, by a work in which he admits reason to the subordinate position of a supporter or commentator, but by no means a foundation or inseparable constituent of an article of the faith. Any thing was better than the blindness and ignorance of the previous age; and questions of the purest metaphysics were debated with a fire and animosity which could scarcely have been excited by the greatest worldly interests. The Nominalists and Realists began their wordy and unprofitable war, which after occasional truces may at any moment break out, as it has often done before, though it would now be confined to the professorial chairs in our universities, and not exercise a preponderating influence on the course of human affairs. The dispute (as the names of the disputants import) arose upon the question as to whether universal ideas were things or only the names of things, and on this the internecine contest went on. All the subtlety of the old Greek philosophies was introduced into the scholasticisms and word-splittings of those useless arguers; and vast reputations, which have not yet decayed, were built on this very unsubstantial foundation.