Полная версия

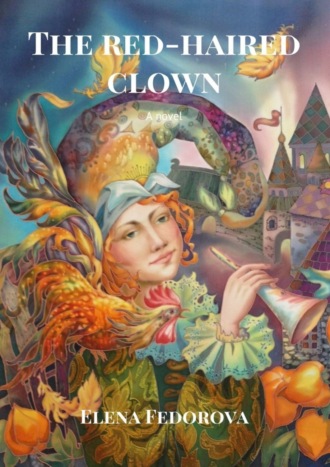

The red-haired clown. A novel

One part goes to Aspasia La Rouge. One part goes to the red-haired clown named…” the banker raised his head, looked at Charles over the top of the glass, and asked:

“What is your name, Mr. Clown?”

“Charles,” he whispered. The banker nodded, lowered his head, and read aloud:

“Named Charles Benosh! It does not matter whether this gentleman marries Simone or not. By forty years he might be a father of a big family. If so, I congratulate him. I ask, I beg him about one thing: to treat my girl as a sister, not to leave her in difficult times.

I hope that Charles Benosh is a decent person, that he will understand that I do not buy his love, his devotion, his friendship. If Charles Benosh is a man of a different sort he may take the money and disappear from the life of Simone Stowasser forever. This is his right,” the banker raised his head, looked at Charles.

“But I believe that the red-haired clown is a man of honour. Otherwise, he would not sit in my house, where evil thoughts of dishonest people are reflected in the hundreds of mirrors like black ghosts. Only a sensitive, sympathetic person with a gentle, sensitive heart can listen to the three-hour chatter of Schwartz Schtanzer, not fearing the shadows of the past that are dancing in the mirrored corridors.

Love my Simone. God bless you. I wish I could shake your hand. Let Schwartz do it for me. Sincerely, George Stowasser. The banker closed the folder, smiled, got up, stepped towards Charles, and held out his hand. Charles hastily got up, shook the banker’s hand, and smiled distractedly.”

“I congratulate you, Mr. Charles Benosh. You have just become a millionaire. By the way, this colour of warm gold suits you.”

“May I ask, Mr. Schtanzer, how Simone’s father found out my name?” Charles asked, feeling that his knees were shaking, and on the back, rolling beads of sweat.

“George was a seer,” the banker smiled. “Sit down, Mr. Benosh, I have to tell you something.”

He put the will aside and sat down in the armchair, having thrown one leg over the other.

“I would like to tell you the story of how Simone and I were looking for the red-haired clown,” he grinned. “It took us six years to find you. Six! The word “circus” was causing me a migraine. I was shaking when I saw painted faces and heard stupid laughs. All red-haired clowns were actually stool pigeons. Some were too old, some were too stupid, too conceited, too great, and so on to infinity. None of them wanted to visit the little girl in the boarding house. Aspasia and I began to panic but Simone, childish frankness, said:

“I will recognize my red-haired clown immediately. Let’s stop unnecessary the conversation with all these respected people.”

“Okay,” I said. “Let’s go to the circus on the outskirts of the town today, and then let’s have an annual respite. Simone agreed. She picked a white dress, hid the hair under big cherry bows, and wrote a note.”

“Today I will see him,” she whispered. “I am telling you beforehand, lest you think I am cheating. I even know that he will choose me for his clown’s trick. And then…” she closed her eyes as if looking at her only visible picture in advance. “He will pick me up and will carry into the arena. Everything happened this way. Do you remember?” Charles nodded. “When Simone gave you a note and sat in the carriage I told her that you were a swaggering fool, like all the previous clowns. I did not like you at all. Your makeup was terrible. Your cherry nose was too big. You had the exaggerated eyes on the white face, the huge mouth from ear to ear,” Schwartz screwed up his face.

“And then, when we were talking near the trailer I was ready to slap you in the face but decided not to upset Simone. She, by the way, immediately said that you were a very nice person. I can see that now. You are smart, well educated, have learned to listen to the interlocutor. Now it is not shameful to invite you in a decent society. And then, sitting in the carriage, I was indignant. I said that you would never come to the boarding house. Simone smiled and said that you would come because you had promised her. Then I promised to pay a hundred ducats to a man, who would bring me such happy news.”

Simone gave me a cool look and said: “You can say goodbye to your ducats right now. The red-haired clown will come to me on Monday.”

“In a hundred years, I smiled. Next Monday, which is tomorrow,” she replied, looking ahead.

“And if he does not come will you have a hundred ducats to pay me?” I asked.

“I will not have to waste your money because the red-haired clown will come. He will definitely come!” she closed her eyes and did not open them to the boarding house.

Simone was sure about you but Aspasia and I did not expect that things would develop with this rapid speed. Besides, we were not waiting for an elegant dandy but a clown in a clownish attire,’ he smiled. ‘Haven’t our secrets yet exhausted you? You are too pale. Would you like some water?”

“No, thank you, it is all right,” Charles said, relaxing neckerchief. “I am just not used to sitting so long in one place, in one position.”

“You can stand up if you want. Only I would recommend you not to stand up not to fall from the next mystery, which…”

“Uncle Schwartz, let me invite you for tea,” the voice of Simone sounded from the depths of the mirrored corridor. Charles saw her reflection and smiled. She was again dressed in the black dress-trap.

“Perhaps, mysteries can wait,” Schwartz said, having gotten up. “Let’s go to the terrace. A breath of fresh air will not hurt. Besides, it is time for the afternoon tea and leisurely conversations about the weather. I hope you are not in a hurry.”

“I am not in a hurry,” Charles said, knowing that he was in a hurry to see Simone, to hear her voice, to look into her in the eyes. He was looking forward to asking about the plum three-year-old Angel with a plaster face, about a tiny brook in a dual willow frame, about their secret summerhouse, where she was teaching him different sciences, and he was telling her about his homeless childhood. Is it possible to lose it? Is it possible to forget this, to exchange this for ducats? He does not need the wealth of Simone Stowasser. It does not matter how much this house, this huge garden, this furniture with gilt are estimated. He is ready to wander around the world in an old, painted bright colours, show-booth, look out the window at the changing scenery, and listen to the song of the squeaky wheels…

“Good afternoon!” the voice of Madame La Rouge sounded like a cello. “You are so elegant tonight, Monsieur Charles as if you came to woo.”

“Yes, you are right. I came to woo,” he replied, looking at Simone. She nearly dropped the teacup.

“Simone,” Madame Aspasia shook her head.

Simone put the cup on the table, sat down on the edge of her chair, dropped her head so low that her chin rested against her chest.

“It is commendable,” Madame Aspasia smiled, picked up the cup, and asked: “Tell me, Monsieur Charles, did you think how the Holy Church would treat a marriage between relatives?”

“No,” he replied, having noticed how Simone startled.

“It is a pity,” Madame Aspasia said, having taken a sip.

The banker began to drum his fingertips on the table, and, grunting “I see”, turned his head away. Aspasia and Charles sat at the table opposite each other. She was freely leaning back in her high chair, behind which the surface of a small pond was glittering. A flock of wild ducks was swimming slowly along the shore, making short stops to dry their wings. The flaps of wings were like the sighs, the cries of despair, the confused misunderstanding that arose in the chest of Charles. He sat on the edge of the chair, ready to dart off and run, run without looking back to the horizon at any moment. What for? To find himself in another place, where no one knows him, where he will be able to start everything all over again. Everything, everything, everything. What for? To prove Simone that she was wrong. He does not succumb to the difficulties. He is not a coward but…

Charles stood up. Madame La Rouge smiled, put the cup down, and nicely laid her thin hands with long musical fingers on her knees.

“I must confess to you, Madame La Rouge, Simone is not my sister,” he said, looking down at the smiling Aspasia. “I claimed to be her cousin in order for you not to kick me out of the house.”

“Bravo, Monsieur Charles,” she said.

“Tell me, have you thought about the fact that Simone, left without parents, can be your sister? You also grew up without parents. Am I right?”

“Yes,” Charles replied. “I am an orphan. My parents passed on long before the birth of Simone, so to search for some connection in our orphanage would be foolish.”

“It would be foolish,” she repeated, having gotten up. “But, nevertheless, there is some connection between them.”

“Are you kidding?” Charles distractedly smiled.

Simone raised her head. Her look was full of despair. Another moment and tears would pour from her eyes.

“Aspasia was not joking,” ceasing to drum on the table, Schwartz said.

“Simone, did you know about this?” Charles whispered, having turned pale. She bit her lip and shook her head.

“She did not know,” Schwartz said, having gotten up.

Simone remained seated. Her body, dressed in the mourning and ceremonial dress, reminded of the monument to the mourner. Charles thought she was petrified. Tear, running down her cheek, was proving that Simone was alive, that it was the same a surprise for her. Charles fell on his knees before her, took her hands, and said: “Simone, do not cry, please. Perhaps, Mr. Schwartz is wrong. The will of your father says nothing about our kinship. It just calls my name. But Benosh is not the last name. It is my stage name. I am the red-haired clown Benosh. Except for the name Charles and the vague childhood memories, I have nothing left from my parents.”

“And how should we do with a birthmark in the form of a comma on his right forearm?” Aspasia asked.

Charles turned his head, looked at her from the bottom up, whispered: “How do you know?”

“George Stowasser told me,” she replied and looked at Schwartz. “It is time to show them a letter from George. Take them to the private office. I can no longer watch what is going on here.”

She turned and, rustling her chocolate satin skirt, left.

“Let’s go to the private office,” the banker said, having taken Simone by the hand. Charles followed them.

“When I was telling Lele that I treated Simone like a younger sister, “he thought, “I was trying more to convince myself, not her, that it was this way. But now, when we are ascribed a kinship, I am terrified. I am crushed by the realization that I am madly in love with my own sister. I just realized that all my feelings are real. Real! Will I ever be able to experience something like that, or will I have a fear of new disappointment? Why do I love her? Why? The Prince has only one Ophelia – Simone Stowasser. But…”

“Come in. Sit down,” Schwartz said, opening the door to the private office.

Charles came in and looked around. There were bookcases with glass doors along the walls from floor to ceiling. There was a large leather sofa. On the opposite side, there was an unpolished desk with one big drawer, from which Schwartz got the folder with the emblem. He hoisted his eyeglasses on his nose, cleared his throat, read: “Dear children!” he looked at Simone and Charles, sitting on the edge of a deep sofa, and grinned. “You are like the frightened birds that fell down from the nests.”

“We are like the prisoners awaiting the death sentence,” Charles said, having firmly gripped his hand of Simone.

“I love,” she whispered and closed her eyes.

“Dear children, I am glad that you have found each other!” Schwartz cheerfully exclaimed. And Charles felt the lump in the throat and wanted to burst into tears. For the first time in many years, he wanted to scream from pain and despair. But he was sitting on the sofa, was looking unwinkingly at the books behind the back of the banker, and was listening. He was waiting for the verdict to be announced, for the guillotine to fall down.

“Simone, the boy next to you is the one, whom you, the five-year-old girl, wanted to save,” Schwartz smiled, looked at Simone.

She opened her eyes, considered for a moment, remembering something, and nodded.

“Do you remember that we went to the circus Chapiteau on the outskirts of the town?” the voice of Schwartz sounded more cheerful. “First, the trapeze artists were flying under the dome, and then, there were the clowns, the red-haired and the white-haired. They brought a boy to the arena and began to push him into the gun instead of the projectile.

You grabbed me by the arm and demanded:

“Dad, save him! Save him immediately.”

“Wait,” having hugged you by the shoulders, I said. “It is the circus, my dear, and nothing bad will happen with the boy, you will see.”

“Something bad has already happened,” you frowned. “Why is he here and not in the gymnasium, as cousin Leo? Where are his parents? Why do they allow the boy to skip classes?”

“Probably, his parents also work in the circus,” I assumed. At this time, the shot rang out, the gun broke into two pieces, the audience was showered with multi-coloured paper stars. The boy bowed and ran backstage together with clowns.

“Dad, please, save him,” you whispered, looking at me with eyes full of tears.

“Simone, this boy is happy. You saw how he smiled happily,” I said.

“Please, dad, you said barely audible. I know, I know that he needs help.”

“Okay,” having shaken your hand, I said.

“We will save your boy. I put you in the landau, while I went to the Director of the circus.”

“What is the name of the boy assistant of the clowns?” I asked, having introduced myself.

“Benosh,” he said. “This boy is not as small as you thought. He is already fifteen. He has a promising future. He will have his own number in the new program. He will become the youngest red-haired clown.”

“Tell me, is Benosh the name of the boy?”

“No, no, his name is Charles,” the Director smiled. “Benosh is a stage name given by the clowns.”

“And who are the parents of this boy?” I asked.

“He is an orphan,” the Director said.

“An orphan boy named Charles,” I said thoughtfully and got up. “Mr. Director, can I ask you for a favour?” he stretched in a string. I put a few large bills on the table and said:

“I will support your circus, and you will support this little clown. Let him keep his stage name. Let him introduce himself as Charles Benosh.”

I promise that we will declare in the new program: the red-haired clown Charles Benosh! the Director promised. I bowed and went out.

On the street, I was almost knocked down by one shock-headed little boy. He was running away from a thick girl, who was shouting something rude at his back.

“Excuse me, Your Honour,” the boy smiled, intending to sneak. I stopped him, wanting to ask him about the boy-assistant of the clowns, but after seeing is a birthmark in the form of a comma on the right forearm, I got speechless. It was that little boy, whom we had been searching for ten years.

“Is your name Charles?” I whispered.

“No, my name is Benosh,” he replied proudly, released, and ran away.

“My dear boy, my dear Charles, I am sorry that I did not tell you everything, that I did not take you with us. I got confused. Yes, yes, confused. For the first time, I did not know what to do, how to be. I went to look for you among the colourful circus trailers. I was stopped by a good-natured fat man, who asked me what I was looking there and grinned.”

“It is easier to catch the wind than our Benosh.”

I turned and walked to the carriage, waiting for me at the exit.

“Simone, you were right,” I said, sitting down opposite her. “This is the boy, whom we must save.”

Schwartz looked at Charles and smiled.

“Do you remember this gentleman?”

Charles nodded. The picture of the past emerged so clearly in his memory as if it all happened a few moments ago. A tall gentleman is looking at him with kind eyes and is smiling. But he, Charles, almost knocked him off his feet, running away from Matilda, the daughter of the Director. The gentleman, for some reason, is talking to him in a whisper. It amuses Charles. He shows his tongue and rushes away. He is passionate about the game, he does not care about the gentleman, walking in the backyard of the circus. Let the adults worry and be concerned. And he, Charles, has nothing to be afraid of. He has not been on the tramp for a long time. He has found protection in the face of Lele and Bebe. Now, he is a clown, the redhaired clown Benosh.

Charles smiled: “I remember this gentleman.”

“Wonderful,” Schwartz said and continued reading letters.

“Mom, mom, we have found the boy, who should be saved!” Simone shouted rushing into the house. Eugenia looked at me frightenedly.

“Yes, my dear, Charles is found,” I smiled.

“Where, where is he” she exclaimed.

“He works in the circus as the red-haired clown,” I replied. Eugenia pressed her hands to her lips, whispered:

“Thank God, the son of Natalie and Edward is alive!”

“Yes, Charles, you are not our son…” Schwartz paused.

“What?” Simone asked.

“What?” Charles straightened his back.

“You are not our son, Charles,” the banker repeated once more. “You are a son of a woman, whom I hopelessly loved. As hopelessly as Schwartz Schtanzer loves Aspasia La Rouge… I saw Natalie for the first time at the ball and lost my mind. I went to her across the room, having forgotten etiquette, having forgotten everything else. I thought she was an ephemeral creature. I was afraid that she would disappear, that I would not be able to talk to her. I do not know why but I wanted to say a few words to her. I did not even think that I could discredit her, that my gesture could be misinterpreted.”

“What do you want?” having blocked Natalie, a man in an expensive uniform, decorated with orders, asked.

“Allow me to pay my respects,” I said, realizing that I made a mistake.

“Edward Benosh,” having held out his hand, he introduced himself. Schwartz looked at Charles over the top of the glass, said: “Yes, yes, young man, Benosh is the last name of your parents.”

“It is surprising,” Charles said. “This name was invented by Lele. Why did she call me like that? I never asked her this. I just accepted my new name as a gift. I was proudly using it all these years, not knowing that it was my last name,” he smiled. “It is nice to regain the lost kinship. I still do not understand what happened to all my numerous relatives? Don’t they want to use the part of the inheritance destined for me? Aren’t they aware of this? Schwartz Schtanzer shrugged, lowered his head, and continued reading.”

“Edward Benosh was an amazing person. We became friends with him. I began to visit their house, large and beautiful house, where a lot of amazing people were gathering. There I met Eugenia Schtanzer the mother of Simone…

If I knew that Edward Benosh was a leader of a secret society of comrades-in-arms, I would try to do something, to help Natalie and Charles. But… I found out about this too late when the house of the Benosh family was turned into the heap of ruins, into the dump of broken dreams.”

“Please, find my Charles,” dying Natalie whispered. “Servants took him somewhere when this mayhem began. I know, I know, he is alive. He must not die. He is not guilty of anything. Find him, George. Save him…”

“Ten years passed before we found you, Charles Benosh. But…” Schwartz cleared his throat. “When we arrived at the circus to take you with us, we only saw the bits of posters, fluttering in the wind. The circus left. Eugenia burst into tears. I was doing my best to console her. And she was crying louder and stronger. Then I ran to the field, gathered sunflowers for her, fell on one knee, and said: “We will certainly find him.”

Eugenia pressed sunflowers to her face, became silent. We came back home, invited Schwartz, and made a will. I wrote this letter a few days later on my own. I needed to get my thoughts together, to calm my heart that was going to burst. This letter is my confession. If Schwartz Schtanzer reads the letter, it means that the bad dream of Eugenia has come true. We are dead… And you are alive! Be happy. Love each other as brother and sister. Be best friends. Be whoever you want, just be, be…

Your George Stowasser.P.S. Oh, I forgot to mention that Natalie Benosh was born at the end of the world, in the town of Charlottenberg. Maybe, you, Charles, would like to find this place. Good luck.”

Schwartz took off his eyeglasses, closed the folder, and smiled: “Now you know everything.”

“Thank you, Mr. Schwartz,” Simone said with a sigh of relief. “I am so happy that Charles is nobody to me. As nobody means everything, the whole world, the whole globe, which I can embrace, press to my chest.” She got up, clasped her shoulders with her arms, and screwed up her eyes. She expected that Charles would get up and kiss her. And he was sitting like a stone idol and was looking at the books behind Schwartz.

“What is it, Charles?” Simone asked, having opened her eyes. “Aren’t you happy? You were afraid that I would want to become your wife, right?”

“No, no,” he said, having rubbed his temples. “Just… Can I take a book?”

“A book?” Schwartz looked at him with annoyance. “Why do you need it?”

Charles got up, came up to the bookcase, took a book in an old binding, opened it, and smiled.

“Yes, this was the book read to me before bedtime by a kind storyteller. For me not to forget his tales, he put a flower, forget-me-not, between the pages.”

Charles turned and showed Simone a flower.

“What a miracle!” she exclaimed. “How old is that flower?”

“Eternity,” Charles said after smelling the pages of the book.

“Now, I understand that back then, before bedtime, your father was telling me the story of his love,” having closed the book, Charles said. On the cover, it was written “The Handbook on Astronomy”. Simone began to laugh.

“Yes, dad loved to read fairy tales from dictionaries and scientific treatises on banking. He wanted his daughter to be the most educated girl on the planet. And here I am…”

Charles hugged her and kissed her on the lips. For the first time. Simone did not expect. She looked at him confused.

“I love you,” Charles whispered, and repeated a little louder:

“I love you, Simone.”

She screwed up her eyes and raised her head. Charles kissed her forehead, eyes, cheeks, pressed his lips to her lips, as to a spream. They did not see how Schwartz Schtanzer quietly left the room, having closed the door behind him. He went to the terrace, where his Aspasia La Rouge was waiting for him. She got up towards him and asked: “Well, how?”

Instead of answering, Schwartz hugged her and began to whirl her.

“What are you doing? Stop this immediately. I am going to faint. Have mercy on me, Schwartz,” Aspasia said. “At my age, it is forbidden to make such sudden movements.”

“At your age, my dear, it is exactly the time to make those movements and to be reckless,” having kissed her upon both cheeks, Schwartz said.

“What are you doing?” she exclaimed, having released out of his embrace.

“I express joy,” he smiled. “You were right, Aspasia. Charles loves Simone. He loves her truly. You won!”

“If I won, then you lost. Are you so happy to lose?” she asked.

“No,” he shook his head, continuing to smile happily. “I am pleased with your insightfulness, your feminine intuition, your strength, your… Madame La Rouge, allow me to kiss you.”

“No,” having proudly thrown back her head, she said.

“I knew this,” Schwartz sighed, impulsively hugged Aspasia and kissed her on the lips.

“You… you…” she looked at him distractedly and turned away.

Schwartz hugged her by the shoulders, whispered:

“Forgive me. Forgive me, dear Aspasia. Consider my act to be foolish childishness. Give me a scolding. Just do not be silent, please.”

She turned and kissed him on the lips. She pushed him away, blushed, looked down, and said:

“If you knew how long I was waiting for this foolish childishness from you, Schwartz.”

“But why didn’t you..?” he exclaimed. She raised her head, looked into his eyes widened in surprise, and confessed: