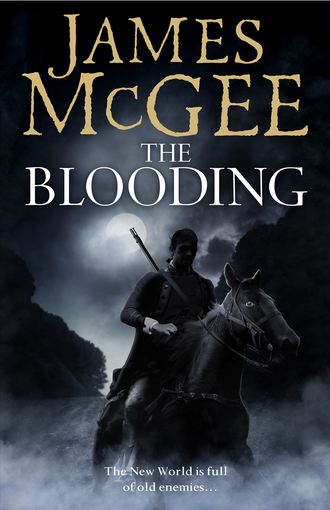

Полная версия

The Blooding

“We got our revenge at Fallen Timbers,” he told Hawkwood. “They had no option after that. They had to sign the damned peace treaty.”

Hawkwood presumed that Fallen Timbers was a battle the Indians had lost. Quade obviously expected him to know about it. Probably best, Hawkwood thought, to remain silent and not disabuse the major of that particular notion.

The Mullahs Quade had referred to were the Berber Muslims. Hawkwood didn’t know much about them either, though he did recall Larkspur’s skipper referring to a war the Americans had fought in the Mediterranean some seven or eight years before against North African pirates.

Following the Legion’s disbanding, Quade had switched his allegiance to the newly resurrected Marine Corps. The Corps had been looking for officers and with the Legion’s mission against the tribes fulfilled, Quade had seen an opportunity for advancement. Since then, by his own admission, the variety of enemy he’d fought against had exceeded that of his father and grandfather.

The major shook his head wearily. “If I’d had any sense, I’d have ignored the call. My ship was in Boston when I heard they were in need of serving officers. Men with experience of engaging with irregulars were especially in demand. I guessed that with my time in the Legion and fighting the Berbers, I had what they were looking for, so I offered my services.”

He gave a rueful smile. “Saw it as the lesser of two evils, my chance to get back to dry land. I’m no sailor, damn it. I always was prone to sea-sickness. Not so good for a Marine, as I’m sure you’ll agree.” He massaged his knee once more. “And look where it got me. That damned river was freezing; it’s a wonder I didn’t come down with pneumonia.”

After his wounds had been treated, Quade was transferred to the hospital at Buffalo, where he’d spent the bulk of his recuperation. With the Americans’ push to invade Canada along the Niagara having stalled, Major Quade had received orders summoning him back to Albany.

“The fact is; I can’t say that I’m looking forward to reporting in,” Quade said quietly, his voice dropping to a whisper, as though he’d suddenly become aware, following his previous indiscretions, that walls could have ears.

“I’m not sure Dearborn’s cut out for command any more than Van Rensselaer was. He’s as old as Methuselah, for a start!” He looked into the fire, staring into the flames for several seconds before pulling back and favouring Hawkwood with a wintry smile. “But you didn’t hear me say that. Forgive me; I’ve a tendency to ramble when I’ve had a few. I meant nothing by it. I dare say you’ll be making your own judgement when the time comes.”

As far as the major was concerned, Captain Hooper was newly arrived from the continent where he’d been on extended service, most recently in Nantes, France, there having undertaken a number of unspecified duties on behalf of a grateful United States Government. Now he was in Albany, awaiting orders from the War Department, on the understanding that he was likely to be assigned to General Dearborn’s Northern Command Headquarters, where his intimate knowledge of British military tactics could be put to strategic use in the current hostilities.

Hawkwood knew that, as masquerades went, it was tenuous at best and downright dangerous at worst, but as his liaison with Quade was only scheduled to last as long as a couple of drinks, hopefully it would suffice.

“It sounds,” Hawkwood said, in an attempt to move the conversation on, “as though the bastards have that part of the frontier sealed up tight. What about Ontario and the St Lawrence? I hear we’ve given a good account of ourselves there.”

Quade’s eyes flashed as he nodded in agreement. “Thanks to Chauncey! About time the bastards got a taste of their own medicine! Now they know what it’s like to be bottled up with nowhere to go!”

From his reading, Hawkwood knew that Commodore Isaac Chauncey, former Officer-in-Charge of the New York navy yard, was the newly appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Great Lakes Navy. Since his transfer to Sackets Harbor in October, the Americans had taken the war to the British with a vengeance. With their successful blockade of Kingston, it was now the United States who ruled the waves on Lake Ontario and the upper reaches of the St Lawrence, and not the Provincial Marine as had previously been the case.

“The Limeys need the Marine to help keep their supply routes open.” Quade said. “We sever those and hopefully we can wear the sons of bitches down. We’ve made a good start. They’re already having difficulty supplying their southern outposts. Once winter sets in, it’ll be impossible to move anywhere. Not that either side will want to, so both armies are going to be snow-bound until March, which means we’ll be ready for them come the thaw.”

Hawkwood manufactured a smile in support of Quade’s rekindled optimism. From the major’s point of view, the reversal of fortune following the Queenston and Detroit defeats was a much-needed boost to national morale, but all Hawkwood could see was the shutting down of his second prospective escape route.

Not that either option had held much appeal, due more to their geography than their military significance. It was four hundred miles to the Niagara frontier and at least two hundred to the St Lawrence, with each route involving a heavily defended river crossing at the end of it.

The third option was looking more inviting by the minute. But then it always had. Quade’s disclosures had merely confirmed what Hawkwood had already decided. If he was to have any chance of reaching safety, he should discount the western paths and take the shortest of the three routes: north, up through New York State. If he made for the closest point on the Canadian border, his journey would still involve the negotiation of a river but, unlike the Niagara and St Lawrence, the Hudson, because of its course, had the potential to be an ally rather than an enemy. Winter was approaching fast, however. If he was going to start his run, he’d need to do it quickly.

Though it wasn’t as if he’d be heading into unknown territory.

The flames in the hearth danced as a new batch of customers entered the tavern, bringing with them a heavy draught of cold air from the street outside. Hawkwood looked towards the door. The new arrivals were in uniform; grey jackets, as opposed to the tan of Quade’s tunic. As they took a table in the corner of the taproom, Quade eyed them balefully over the rim of his now-empty glass.

“Pikemen,” he murmured scornfully. “God save us. It’ll be battleaxes next.”

Hawkwood knew his puzzlement must have shown, for Quade said, “My apologies; a weak jest. They’re Zebulon Pike’s boys. Fifteenth Infantry. He’s had them in training across the river.”

“Across the river” meant the town of Greenbush. Hawkwood had been surprised and not a little thankful to discover that Albany wasn’t awash with military personnel. It had turned out that General Dearborn had set up his headquarters not in the town but in a new, specially constructed compound on the opposite side of the Hudson. This was much to the relief of the locals, who, while mindful of the economic advantages of having an army camped on their doorstep, didn’t want the inconvenience of several thousand troops living in their midst. It was a compromise that suited all parties.

“Battleaxes?” Hawkwood said, confused.

“Pike has this notion to equip his men with pole-arms. He’s introduced a new set of drills: a three-rank formation. First two ranks armed with muskets, the third with pike staffs. He reckons it’ll enable a battalion to deploy more men in a bayonet charge.”

“It does sound medieval,” Hawkwood agreed warily.

Quade grunted. “That was my thinking, though there could be some sense in it, I suppose. Most third ranks are next to useless when it comes to attacking in line. Even with bayonets fixed, their muskets are too short to be effective. A line of twelve-foot pikes would certainly do the trick. Would you face a line of men armed with twelve-foot pikes?”

“Only if I had fifteen-foot pikes,” Hawkwood said. “Or lots of guns.”

“So, maybe I stand corrected,” Quade said. “I’m sure they’ll give a good account of themselves when it’s required.” He eyed the recent arrivals. “They’ll be enjoying their last drink before heading north to join the rest.”

“The rest?” Hawkwood said.

There was a pause.

“They did tell you that Dearborn’s in Plattsburg,” Quade said. “Didn’t they?”

Hawkwood raised his glass and took a swallow to give himself time to think and plan his response.

“I only landed in Boston a few days ago. No one’s told me a damned thing.”

Quade shook his head and made the sort of face that indicated he despaired of all senior staff.

“Typical. Just as well we met then, though you’d have found out eventually. He’s been there since the middle of last month. Winter quarters. Pike’s up there with him. I’ve no doubt my orders will be to join them, which is why I’m in no hurry to return to the bosom. I’ve a day or two of freedom left and I intend to make the most of them.”

He sighed, stared into his glass and then, clearly making a decision, stood it on the table between them.

“Another?” Hawkwood asked.

To Hawkwood’s relief, the major shook his head. “Thank you, that’s most generous, but on this occasion I’ll decline. I’ve a prior appointment and, no disrespect, Captain, but she’s a damned sight prettier than you are!” Quade grinned as he reached for his coat and cane. “A tad more expensive, but definitely prettier.”

“In that case, Major,” Hawkwood said, “don’t let me detain you.” He waited until Quade had gained his feet and then accompanied the major as he tapped his way towards the door.

On the street, the major paused while buttoning his coat. “If you’re free, why don’t you join me?”

“Another time, perhaps,” Hawkwood said.

Quade, not in the least put out, smiled amiably. “As you wish. If you should change your mind, you’ll find us on Church Street – the house with the weathercock on the roof. The door’s at the side. There’s a small brass plate to the right of it: Hoare’s Gaming Club. It—”

Seeing the expression on Hawkwood’s face, the major chuckled and spelt out the name. “Yes, I know, but what would you have it say – the Albany Emporium? Anyway, as I was saying, it caters for the more – how shall I put it? – discerning gentleman, so you’d be in excellent company. A lot of the senior officers from Greenbush take their pleasure there.”

Another reason for giving the place a wide berth, Hawkwood thought. “Well, I’ll certainly bear that in mind, Major, if I find myself at a loose end.”

“Ha! That’s the spirit! All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy, eh? Besides, we’re at war. Who’s to say we shouldn’t enjoy what could be our last day on earth before we head to the front?”

“I thought everyone was going to be snowed in for winter,” Hawkwood said. “There won’t be a front until March.”

“Ah, but the ladies don’t know that, do they?”

God save us, Hawkwood thought.

As an ear-splitting shriek shattered the surrounding calm.

Hawkwood pivoted. Heart in mouth, he paused as a broad grin of delight opened up across the major’s face.

“Ha!” Quade exclaimed gleefully. “Had the same effect on me, the first time I heard it. Thought it was the cry of the banshee come to carry me off! They do say it’s caused seizures in at least half a dozen of the city’s older female folk. Not seen her before? Quite a sight, ain’t she?”

The major pointed with his cane.

As his pulse slowed to its normal rate, Hawkwood, embarrassingly aware that other passers-by had not reacted as he had, looked off to where Quade was indicating. They had come to a halt adjacent to the river. Only the width of the street and a patch of open ground separated them from the quayside and the vessels moored alongside it.

The Hudson was Albany’s umbilical. It was from the busy wharves and slipways crowding the mile-long shoreline that goods from the city’s granaries, breweries and timber yards were transported downriver to the markets of New York, one hundred and fifty miles to the south.

Scores of cargo sloops and passenger schooners competed for mooring space with smaller barges and hoys. It could have been a scene lifted from the Thames or the Seine, had it not been for the tree-clad hillsides rising from the water on the opposite shore and the extraordinary-looking vessel that was churning into view beyond the intermediary forest of masts and rigging. The throbbing sounds that enveloped the craft as it manoeuvred towards the jetty were as curious as its appearance and like nothing Hawkwood had heard before.

There was no grace in either its movement or its contours. Compared to the other craft on the river, it occurred to Hawkwood that the clanking behemoth, with its wedged bow and wall-sided hull had all the elegance of an elongated canal boat, while the thin, black, smoke-belching stove-pipe poking up from the boat’s mid-section wouldn’t have looked out of place on the roof of a Cheapside tenement.

The threshing sound was explained by what appeared to be two large mill wheels, their top halves set behind wooden housings on either side of the hull, forward of the smoke-stack. They were, Hawkwood saw, revolving paddles; it was their rotation that gave the vessel its momentum through the water.

Another drawn-out screech rent the air, sending a flock of herring gulls, already displaced by the first whistle, wheeling and diving above the nearby rooftops in raucous protest.

Quade moved to Hawkwood’s side. “She’s the Paragon, up from New York. She can do six and a half knots at a push. Seven dollars a ticket, I’m told, and it only takes thirty-six hours. It takes the schooners four days. You’ve not seen any of them in action?”

Hawkwood shook his head and watched as the steamboat shuddered and slowed. For a few seconds the clattering from her paddles seemed to diminish before suddenly increasing in volume once more. Hawkwood realized the wheels were now revolving in the opposite direction and that the vessel was travelling in reverse.

“Takes ninety passengers,” Quade said matter-of-factly as the boat’s stern started to come round. “Fulton used to swear they could turn on a dollar – the boats, that is, not the passengers. Don’t know if that’s strictly true. No one’s thrown a dollar in to find out.” He chuckled.

For a moment Hawkwood thought he might have misheard.

“Fulton?” he repeated cautiously, trying to keep his tone even.

“Robert Fulton,” Quade said. He looked at Hawkwood askance. “Good God, man, you must have heard of him! How long did you say you’d been away?”

Hawkwood said nothing. His mind was too busy spinning.

Fulton?

It had to be the same man. Robert Fulton, American designer of the submersible, Narwhale, in which Hawkwood had fought hand to hand with Fulton’s associate, William Lee, beneath the dark waters of the Thames, following Lee’s failed attack on the newly launched frigate, Thetis.

Hawkwood had killed Lee and left his body entombed at the bottom of the river, inside Narwhale’s shattered hull. It seemed like an age ago, yet memory of a discourse he’d had with the Admiralty Board members and the scientist, Colonel William Congreve, prior to the discovery of Lee’s plan, slid into his mind. Hawkwood heard an echo of Congreve’s voice telling him that at the same time as Fulton had been petitioning the French government to support his advances in undersea warfare, he’d also been experimenting with steam as a means of propulsion.

Hawkwood stared at the vessel, which was now side on to the quay, and watched as mooring lines were cast fore and aft. While Fulton’s dream of liberty of the seas and the establishment of free trade through the destruction of the world’s navies might lie in tatters at the bottom of the Thames, it appeared that his plans for steam navigation had achieved spectacular success.

“Can’t say the schooner skippers are best pleased,” Quade said. “They’ve lost a deal of passenger trade since the steamboats started running.”

“How many are there?” Hawkwood asked.

“I believe it’s five or six at the last count. I do know that two of them operate alternating schedules up and downriver. Others are used as ferries around New York harbour.”

“I’ll be damned,” Hawkwood said, nodding as if impressed. “Y’know, the time’s gone so quickly … I’m blessed if I can remember when they did start.”

“Back in ’07.” Quade leaned on his stick and gazed admiringly at the boat as the gangplank was extended. “If you recall, Clermont was the first. It made its maiden run that August.”

The year after Fulton had left London to return home. The British government had thought that his departure meant they would hear no more of the American and his torpedoes – until Lee’s appearance five years later.

“Of course,” Hawkwood said. “How could I forget?”

“Not the most amenable fellow, I’m told,” Quade murmured. “Arrogant, and not much liked, by all accounts, though you can’t deny he’s a clever son of a bitch. There’ve been rumours he’s trying to design some kind of military version, but last I heard, he’s not in the best of health, so I wouldn’t know how that’s proceeding.”

With the steamship now berthed and its passengers disembarking, Hawkwood was able to take stock of her. She was, he guessed, about one hundred and fifty feet in length, with the top of the smoke-stack rising a good thirty feet above the deck. There were two masts: one set forward and equipped for a square sail, the other at the stern, supporting a fore and aft rig. The sails, Hawkwood presumed, were to provide her with additional impetus if her engine failed. The paddle wheels had to be at least fifteen feet in diameter. There was no bowsprit and no figurehead. Even to an untrained eye, with no attempt having been made to soften her lines, it was plain the vessel had been constructed entirely for purpose. As if to emphasize the steamboat’s stark functionality, the top of the cylindrical copper boiler, set into a rectangular well in the centre of the deck and from which the smoke-stack jutted, was fully exposed, not unlike the protruding intestines of a dissected corpse.

“They say the machine that controls her wheels has the power of thirty horses,” Quade offered admiringly. “I’ve no idea how they work that out. I can only assume they tied them to her bow and held a tug of war. Your guess is as good as mine.” The major shook his head in wonder. “Y’know, there’s also a story that Fulton tried to interest Emperor Bonaparte in an undersea boat, and when that didn’t work he changed his allegiance and approached the Limeys for funding. Sounds a bit far-fetched, if you ask me. Not sure I believe it, frankly.”

“It does sound unlikely,” Hawkwood agreed.

“Well, he’s on our side now, and that’s the main thing,” Quade said. He reached into his coat and dug out a pocket watch. Flipping the catch, he consulted the dial and tutted. “Damn, I should go – wouldn’t like young Lavinia to start without me. If they do insist on sending me up into the wilds, this could be our last ah … consummation for a while.” Snapping the watch shut, he looked at Hawkwood and cocked an eyebrow. “You’re sure you won’t …?” He left the suggestion hanging open.

Hawkwood shook his head. “Enjoy yourself, Major.”

Quade tucked the watch away and grinned. “Oh, I intend to, don’t you worry.” He extended his hand. “My thanks for your intervention, Captain. It was good to meet you. We’ll likely run into each other again, I expect, after we’ve taken up our duties; either here or at Greenbush. They’re small towns, when all’s said and done. That’s if they don’t send us to Plattsburg, of course. Or if you’d like to meet for a libation before then, you’ll likely find me at the Eagle or Berment’s. I’ve taken a room there.”

“That’s most kind, Major. Thank you.”

“Excellent, then I’ll bid you good day.”

And with a final wave of goodbye, Major Quade limped off to his assignation.

Hawkwood watched him go and wondered idly if the major’s leg would hold out during his impending exertions.

Coat collar turned up, he gazed out over the water. The sky was the colour of tempered steel. Colder weather was undoubtedly on the way, bringing snow, and it was more than likely the river would eventually freeze over. Could steamboats navigate through ice? Hawkwood wondered. Perhaps, if it wasn’t too thick. But, presumably, if the weather really did close in, even they’d be forced to stop running.

Hopefully, he’d be long gone by that time.

Reaching into his pocket, he withdrew the page he’d torn from The War in the Exchange’s reading room. It wasn’t the most comprehensive map, and it was probably safe to assume that the hand-drawn features had been copied from a much more detailed engraving, so the scale was undoubtedly out of proportion as well, yet all the relevant information appeared to be in place.

Most of New York State was outlined, from Vermont in the east across to the St Lawrence River and the Niagara Frontier in the west. Major towns were marked, as were the main rivers and the largest lakes. The front lines were represented by cannons and flags. Small crenellated squares and anchors showed forts and naval bases. Crudely drawn arrows indicated advances and retreats. The symbols were at their most prolific around the western borderlands, confirming what Major Quade had told him.

Albany, rather than Greenbush, was shown due to its significance as the state capital. It was surmounted by a drawing of a fort topped by the stars and stripes. The next nearest American military presence deserving of capital letters and distinguishable by another tiny fort, was Plattsburg, where Dearborn had set up his winter camp.

Hawkwood shifted his gaze north, at the river and the landscape that lay beyond. He’d been fresh from a return visit to the State Street coach office and mulling over the choices that had been presented to him by the ticket clerk when he’d encountered the major. Now that Quade had confirmed his suspicions over which was the most advantageous route to Canada, there was still the mode of transport to consider. Hawkwood had no intention of walking all the way to the border.

Albany had received its capital status due to it having become the centre of commerce for the north-eastern states. Post roads ran through the city like spokes on a wheel. The most important one – referred to by the clerk as the Mohawk Turnpike – which led directly eastwards through Schenectady to Utica and on to Sackets Harbor, Hawkwood had already dismissed. It was only when the clerk had listed the intermediate halts along the route, that a cold hand had clamped itself around his heart at the mention of one particular name.

Johnstown.

It was a name from a life time ago and one he’d not thought of for many years. Knowing that his reaction must have shown and aware that the clerk was giving him an odd look, Hawkwood had forced his mind to return to the present.

There was an alternative route, the clerk told him. The northern turnpike, which formed part of the New York to Montreal post road. Though, unfortunately, it was also prone to flooding after heavy rain. In fact, the clerk had warned, stretches of it between Albany and Saratoga had already become impassable due to the recent torrents.

What about the river? Hawkwood had enquired, his mind half occupied with trying to shut out the echo from his past.

The clerk had shaken his head. The Hudson was only navigable as far as Troy, six miles upstream. There might be batteaux travelling further north, but Hawkwood would have to investigate that possibility himself by talking to one of the local boat captains.

Hawkwood had been on the point of turning away when the clerk said, “Might I suggest the ferry to Troy, sir? You could pick up the eastern post road there. It runs all the way to Kingsbury and from there along the old wagon road to Fort George, where it links on to the turnpike you would have taken. See here …”