Полная версия

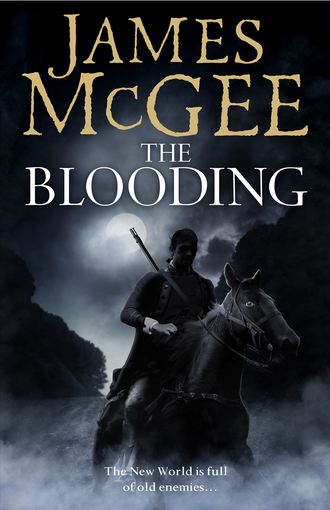

The Blooding

“Bitch!” Spitting out the obscenity, Smede aimed his musket at Beth Archer. The gun belched flame. Without waiting to see if the ball had struck, he tossed the discharged weapon aside and clawed for his pistol.

Meeker, meanwhile, had managed to scramble clear of his horse. Retrieving his musket, he turned to see where the shot had come from, only to check as a ball took him in the right shoulder, spinning him like a top.

Archer, on the ground, venting blood and trying to make sense of what was happening, found Jeremiah Kidd staring at him in puzzlement and fear. And then Archer realized that Kidd wasn’t staring at him he was staring past him. Archer squirmed and looked over his shoulder. Through eyes blurring with tears he could see four men in uniform, hard-looking men, each carrying a long gun. Two of them were drawing pistols as they ran towards the house.

Another crack sounded. This time it was Kidd who yelped as a ball grazed his arm. Wheeling his horse about, he dug his heels into the mare’s flanks and galloped full pelt in the direction of the stream.

Only to haul back on the reins, the cry rising in his throat, as a vision from hell rose up to meet him.

Wyatt, discharged rifle in hand, stepped out from the side of the barn. He’d been surprised when Archer had shot Smede, assuming that Deacon would be the farmer’s first target. It had taken only a split second to alter his aim, but he’d not been quick enough to prevent Deacon’s retaliation. As a result, Archer was already on his back by the time Deacon met his emphatic demise, courtesy of Wyatt’s formidable, albeit belated, marksmanship.

It had been Jem Beddowes, Wyatt’s fellow Ranger, who’d shot Meeker’s horse from under him. Beddowes had been aiming at the rider, but the horse had shied at the last moment, startled by the volley of gunshots, and the ball had struck the animal instead, much to Beddowes’ annoyance. His companion, Donaldson, had compensated for the miss by shooting Meeker in the shoulder, which had left the fourth Ranger – Billy Drew – and Tewanias with loaded guns, along with two functioning rebels, the younger of whom, to judge by the way he was urging his horse towards the stream, was fully prepared to leave his companions to their respective fates.

Isaac Meeker, meanwhile, having lost his musket for the second time, pushed himself to his knees. Wounded and disoriented, he stared around him. His horse had ceased its death throes and lay a few feet away, its belly stained with blood from the deep wound in its side. Deacon and Levi Smede were sprawled like empty sacks in the dirt, their mounts having bolted. Half of Deacon’s face was missing.

He looked for Shaw and saw that the postmaster had fallen from his horse and was on the ground, trying to crawl away from the carnage. The musket looped across Shaw’s back was dragging in the dirt and acting like a sea anchor, hampering his progress. He was whimpering in agony. An uneven trail of blood followed behind him.

A fresh shot sounded from close by. Not a long gun this time, but a pistol. Meeker ducked and then saw it was Ephraim Smede, still in the saddle, who had fired at their attackers. Meeker looked around desperately for a means by which to defend himself and discovered his musket lying less than a yard away. Reaching for it, he managed to haul back on the hammer and looked for someone to shoot. He wasn’t given the chance. Ranger Donaldson fired his pistol on the run. The ball struck the distracted Meeker between the eyes, killing him instantly.

Ephraim Smede felt his horse shudder. He’d been about to make his own run for the stream when Billy Drew, having finally decided which of the two surviving riders was the most dangerous, took his shot.

The impact was so sudden it seemed to Smede as if his horse had run into an invisible wall. One second he was hunkered low in the saddle, leaning across his mount’s neck, the next the beast had pitched forward and Smede found himself catapulted over its head like a rock from a trebuchet. He smashed to the ground, missing Shaw’s prostrate body by inches. Winded and shaken, he clambered to his knees.

He was too engrossed in steadying himself to see Ranger Beddowes take aim with his pistol. Nor did he hear the crack nor see the spurt of muzzle flame, but he felt the heat of the ball as it struck his right temple. Ephraim Smede’s final vision before he fell was of his brother’s lifeless eyes staring skywards and the dark stain that covered Levi’s chest. Stretching out his fingers, he only had time to touch his brother’s grubby coat sleeve before the blackness swooped down to claim him.

Determining the rebels’ likely escape route had not been difficult and Wyatt, in anticipation, had dispatched Tewanias to cover the stream’s crossing place.

It was the Mohawk warrior’s sudden appearance, springing from the ground almost beneath his horse’s feet, that had forced the cry of terror from Jeremiah Kidd’s throat. The mare, unnerved as much by her rider’s reaction as by the obstacle in her path, reared in fright. Poor horsemanship and gravity did the rest.

The earth rose so quickly to meet him, there was not enough time to take evasive action. Putting out an arm to break his fall didn’t help. The snap of breaking bone as Kidd’s wrist took the full weight of his body was almost as audible as the gunshots that had accompanied his dash for freedom.

As he watched his horse gallop away, Kidd became aware of a lithe shape running in. He turned. His eyes widened in shock, the pain in his wrist forgotten as the war club scythed towards his head.

The world went dark, rendering the second blow a mere formality, which, while brutal in its execution, at least saved Kidd the agony of hearing Tewanias howl with triumph as he dug his knife into flesh and ripped the scalp from his victim’s fractured skull. Brandishing his prize, the Mohawk returned the blade to its sheath and looked for his next trophy.

Archer knew from his years of soldiering and by the way the blood was seeping between his fingers that his condition was critical. He looked towards the porch, where a still form lay crumpled by the cabin door. A cold fist gripped his heart and began to squeeze.

Beth.

Hand clasped against his side, Archer dragged himself towards his wife’s body. He tried to call out to her but the effort of drawing air into his lungs proved too much; all he could manage was a rasping croak.

Why hadn’t she done as she was told? he thought bleakly. Why hadn’t she stayed inside? His slow crawl through the dirt came to a halt as a shadow fell across him.

“Don’t move,” a voice said gently.

He looked up and found himself face to face with one of the uniformed rifle bearers.

A firm hand touched his shoulder. “Lieutenant Gil Wyatt, Ranger Company.”

“Rangers?” Archer blinked in confusion and then, as the significance of the word hit him, he made a desperate grab for Wyatt’s arm. “My wife; she’s hurt!”

“My men will see to her,” Wyatt said. He flicked a glance at Donaldson, who crossed swiftly to the cabin. “Let me take a look at your wound.”

“No!” Archer thrust away Wyatt’s hand. “She needs me!”

He tried to push himself off the ground, but the effort proved too much and he sank down. “Help her,” he urged. “Please.”

Wyatt looked off to where Donaldson was crouched over the fallen woman. A grim expression on his gaunt face, the Ranger shook his head. Laying his hand on Archer’s shoulder once more, Wyatt helped him sit up. “I’m so very sorry. I’m afraid we’re too late. She’s gone.”

The wounded man let out a cry of despair. Knowing that nothing he could say would help, Wyatt scanned the clearing. Twenty minutes ago, he had been up on the hill, admiring the tranquillity. Now the ground seemed to be strewn with bodies. As Donaldson covered the woman’s face with a cloth, Wyatt turned back to her husband.

Archer made no protest as Wyatt prised his hand from the wound, but he could not suppress a gasp of pain as the Ranger opened the bloodied shirt.

One glance told Wyatt all he needed to know. “We must get you to a surgeon.”

The nearest practitioner was in Johnstown, but to deliver the wounded man there would be asking for trouble. An army surgeon and a brace of medical assistants had accompanied the invasion force. They were the farmer’s best chance.

Although, given his current condition, Wyatt doubted whether the wounded man would survive the first eight yards, let alone the eight miles they’d need to traverse across what was, in effect, hostile country.

He looked off towards the paddock, where the horses were staring back at him, ears pricked. Wyatt could tell they were skittish, no doubt agitated by the recent skirmish, but it gave him an idea.

“Is there a cart or a wagon?” he asked.

“The barn,” Archer replied weakly. He tried to point but found he couldn’t lift his arm.

“Easy,” Wyatt said. Cupping the farmer’s shoulder, he called to his men. “Jem! Billy! There’s transport in the barn! Hitch up the horses! Smartly now!”

As he watched them go, he heard a murmur and realized the farmer was speaking to him. He lowered his head to catch the words.

“You’re Rangers?” Archer enquired hoarsely as his lips tried to form the question. “What are you doing here?”

“We came for you,” Wyatt said.

“Me?” Puzzlement clouded the farmer’s face.

“You and others like you. We’re here under the orders of Governor-General Haldimand. When he learned that Congress was threatening to intern all Loyalists, he directed Colonel Johnson to lead a force across the border to rescue as many families as he could and escort them back to British soil.”

Archer stared at him blankly. “Sir John’s returned?”

“Two nights ago. With five hundred fighting men, and a score to settle. Scouting units have been gathering up all those who wish to leave, from Tribe’s Hill to as far west as the Nose.”

“There’s not many of us left.” Archer spoke through gritted teeth. “Most have already sold up and gone north after having their barns burned down and their homes looted, or their cattle maimed or poisoned.” Sweat coating his forehead, he winced and pressed his hand to his side until the wave of pain subsided enough for him to continue. “All for refusing to serve in home defence units. This wasn’t the first visit I’d had but this time they were threatening to throw me in prison and take my farm.”

“Those men were militia?”

“Citizens’ Committee. They were under orders to take me to Johnstown to pledge allegiance to the flag. I told them to ride on.” The farmer bowed his head. “I should have gone with them.” He looked towards the cabin and his face crumpled.

“You weren’t to know it would end like this,” Wyatt said softly. “If I’d realized who they were, I’d have given the order to intercede sooner.”

His face pinched with pain and grief, Archer looked up. “How many have you gathered so far?”

“A hundred perhaps, including wives and children and some Negro slaves. They’re all at the Hall. It’s the rendezvous point.”

There was no response. Wyatt thought the farmer had passed out until he saw his eyelids flutter open, the eyes casting about in confusion before suddenly opening wide. As Wyatt followed his gaze in search of the cause, the breath caught like a hook in his throat.

Ephraim Smede came to with blood pooling along the rim of his right eye socket. He blinked and the world took on a pinkish sheen. He blinked again and his vision began to clear. He was aware that the gunfire had ceased but an inner voice, allied to the pain from the open gash across his forehead, told him it would be better to remain where he was so he lay unmoving, listening; alert to the sounds around him.

A few more seconds passed before he raised himself up. He did so slowly. His first view was of his brother’s corpse. Beyond Levi, he could see the bodies of their companions, along with the two dead horses. Pools of blood were soaking into the ground, darkening the soil. Flies were starting to swarm.

He could hear voices but they were low and indistinct. He couldn’t see who was speaking because the rump of Isaac Meeker’s dead nag blocked his line of sight.

It occurred to Smede that he was probably the only one of Deacon’s party left alive. From the looks of Axel Shaw, he must have bled to death. There was no sign of Kidd, but Smede doubted the youth would have survived the ambush – or stuck around if he had.

Which meant he was on his own, with a decision to make. Inevitably, his eyes were drawn to his brother’s glassy stare and a fresh spark of anger flared within him.

As his gaze alighted on Levi’s pistol.

A low moan came from close by. Smede dropped down quickly. He held his breath, waiting until the sound trailed off before cautiously raising his head once. Will Archer was propped some twenty paces away. One of the green-clad men was with him; he shouted something and two of the attackers ran immediately towards the barn.

Another movement drew Ephraim’s attention. A second pair was rounding up the horses. One of them, Ephraim saw to his consternation, was an Indian. His startled gaze took in the face paint and the weapons that the dark-skinned warrior carried about him. There was also what appeared to be a lock of hair hanging from his breechclout.

Bile rose into the back of Ephraim’s throat. Escape, he now realized, wasn’t only advisable; it was essential.

He watched through narrowed eyes, nerves taut, as the two Rangers pulled open the barn door and disappeared inside. Quickly, his gaze turned back to the pistol lying a few feet away. He looked over his shoulder.

Now, he thought.

Concealed by Meeker’s horse, Smede inched his way towards the unguarded firearm until he was able to close his fingers around the gun’s smooth walnut grip.

He took another deep breath, gathering himself, waiting until the Indian’s attention was averted. One chance at a clear shot; that’s all he would get.

And then he would run.

He knew the woods like the back of his hand; if he could just make it to the trees, the forest would hide him.

Maybe.

His main fear was the Mohawk, because the pistol, with its single load, was all he had. But his brother’s killer came first. An eye for an eye, so that Levi could go to the grave knowing that his brother had exacted revenge. So …

In one fluid motion, Smede snatched up the gun, rose to his feet, took aim, and fired.

As the blood-smeared figure tilted towards them, Wyatt, caught between supporting the wounded Archer and reaching for his weapon, let out a yell. Alerted by his cry, Tewanias and Donaldson both turned.

Too late.

The ball thudded into Archer’s chest and he collapsed back into Wyatt’s arms with a muffled grunt.

Whereupon Ephraim Smede, who was about to launch himself in the direction of the woods, paused, his features suddenly distorting in a combination of shock, pain and disbelief. Mouth open, he uttered no sound as his body arched and spasmed in mid-air.

As Wyatt and the others looked on in astonishment, Smede’s legs buckled and, one hand clutching the spent pistol, he pitched forward on to his face.

It wasn’t until the body struck the ground that Wyatt saw the stem of the hatchet that protruded from the base of Smede’s skull and the slim figure that, until then, had been blocked from view by Smede’s temporarily resurrected form.

“No!” Coming out of his trance, Wyatt threw out his arm.

Tewanias, whose finger was already tightening on the trigger, paused and then slowly lowered his musket. A frown of puzzlement flickered across the war-painted face.

Wyatt felt a tremor move through Archer’s body. It was obvious from the uneven rise and fall of the wounded man’s chest that death was imminent.

The eyes fluttered open one last time and focused on Smede’s killer with a look that might have been part relief and part wonderment. Then his expression broke and he grabbed Wyatt’s sleeve and pulled him close.

Wyatt had to bow his head to catch the words:

“Keep him safe.”

The farmer’s head fell against Wyatt’s arm. Wyatt felt for a pulse but there was none. He looked up.

The boy, though tall, couldn’t be much more than eleven or twelve years old. For all that, the expression on his face was one that Wyatt had seen mirrored by much older men when the battle was over and the scent of blood and death hung in the air.

A shock of dark hair flopped over the boy’s forehead as his eyes took in the scene of devastation, his jaw clenching when he saw the body on the porch. Running across the clearing to where Wyatt was crouched over the farmer’s body, he fell to his knees.

Close to, Wyatt could see tear tracks glistening amid the grime on the boy’s face. A trembling hand reached out and gently touched the dead man’s arm.

“Aunt Beth told me to hide in the cellar, but I came back up.” The boy looked to where Ephraim Smede’s corpse lay in the dirt. “I saw that man shoot her. Then he fell off his horse and I thought he was dead. But he was only pretending.”

The boy’s voice shook. “I wanted to warn you, but there was shooting out front, so I went round the back by the woodpile. I saw the man pick up the gun. I was too scared to call out in case he saw me. I picked up the axe thinking I might scare him. Only I was too late. He …” The boy paused. “He shot Uncle Will, so I hit him as hard as I could.”

The boy’s voice gave way. Fresh tears welled. Letting go of the farmer’s arm, he lifted a hand to wipe the wetness from his cheeks and looked over his shoulder, his jaw suddenly set firm. “He won’t hurt anyone again, will he?”

“No,” Wyatt said, staring at the axe handle. “No, lad, he won’t.”

An equine snort sounded from close by. Wyatt, glad of the distraction, saw it was Tewanias and Donaldson returning with the captured mounts. Behind them, Billy Drew, flanked by Jem Beddowes, was leading one of the two farm horses, harnessed to a low-slung, flat-bed cart.

As they caught his eye, Wyatt gently released the farmer’s body, stood up and shook his head. “Sorry, Billy. We won’t be needing it after all.”

“He’s gone?” Drew asked.

“Aye.”

“Son?” Drew indicated the boy.

“Nephew,” Wyatt said heavily. “Far as I can tell.”

“Poor wee devil,” Drew said. Then he caught sight of the axe. “Jesus,” he muttered softly.

“What’ll we do with them?” Donaldson enquired, indicating Deacon and the other dead Committee members.

“Not a damned thing,” Wyatt snapped. “They can lay there and rot as far as I’m concerned.”

“Seems fair.” Donaldson agreed, before adding quietly, “And the other two?”

“Them we do take care of. They deserve a decent burial, if nothing else. See if you can find a shovel. It’s a farm. There’ll be one around somewhere.”

“And then?” Beddowes said.

“And then we report back.”

“The boy?”

“He comes with us,” Wyatt said. “We might as well take advantage of the horses, too.” He turned. “Can you ride, lad?”

The boy looked up. “Yes, sir. That one’s mine. He’s called Jonah.” He indicated the horse that Billy Drew had left in the paddock. It was the smaller one of the two.

“There was tack in the barn,” Beddowes offered.

Wyatt turned. “Very well, saddle him up and take this one back. Make sure he’s got plenty of feed and water. We’ll see to the rest.” Wyatt addressed the boy. “You go with Jem; show him where you keep Jonah’s blanket and bridle.”

Hesitantly, the boy rose to his feet. Wyatt waited until he was out of earshot, then turned to the others.

“All right, we’d best get it over with.”

They buried Archer and his wife in the shade of a tall oak tree that grew behind the cabin, marking the graves with a pair of wooden crosses made from pieces of discarded fence post. Neither one bore an inscription. There wasn’t time, Wyatt told them.

Donaldson, whose father had been a minister, was familiar with the scriptures and carried a small bible in his shoulder pouch. He chose the twenty-third psalm, reading it aloud as his fellow Rangers bowed their heads, caps in hand, while the Indian held the horses and looked on stoically.

The scalp had disappeared from the Mohawk’s breechclout. When he’d spotted it, Wyatt had reminded Tewanias of the colonel’s orders: no enemy corpses were to be mutilated. It was with some reluctance that Tewanias returned to the river and laid the scalp across the body of its original owner.

“Let it act as a warning to those who would think to pursue us,” Wyatt told him. “Knowing we are joined with our Mohawk brothers will make our enemies fearful. They will hide in their homes and lock their doors and tremble in the darkness.”

Wyatt wasn’t sure that Tewanias was entirely convinced by that argument, but the Mohawk nodded sagely as if he agreed with the words. In any case, both of them knew there were likely to be other battles and therefore other scalps for the taking, so, for the time being at least, honour was satisfied.

The boy stood gazing down at the graves with Wyatt’s hand resting on his shoulder. The dog, Tam, lay at his side, having been released from the cabin when, under Wyatt’s direction, the boy had returned to the house to gather up his possessions for the journey.

Donaldson ended the reading and closed the bible. The Rangers raised their heads and put on their caps.

“Time to go,” Wyatt said. “Saddle up.” He addressed the boy. “You have everything? You won’t be coming back.” The words carried a hard finality.

Tear tracks showing on his cheeks, the boy pointed at the canvas bag slung over his saddle.

Wyatt surveyed the yard – littered with the bodies of Deacon and his men – and the blood-drenched soil now carpeted with bloated flies. It was a world away from the serene, sun-dappled vision that had greeted the Rangers’ arrival earlier that morning.

He glanced towards the three cows in the paddock and the chickens pecking around the henhouse; the livestock would have to fend for themselves. There was enough food and water to sustain them until someone came to see why Archer and his wife hadn’t been to town for a while. There would be others along, too, wondering why the members of the Citizens’ Committee hadn’t returned to the fold.

Let them come, Wyatt thought. Let them see.

The Mohawk warrior handed the boy the reins of his horse and watched critically as he climbed up. Satisfied that the boy knew what he was doing, he wheeled his mount and took up position at the head of the line. With Tewanias riding point, the five men and the boy rode into the stream, towards the track leading into the forest. The dog padded silently behind them.

Halfway across the creek, the Indian turned to the boy and spoke. “Naho:ten iesa:iats?”

The boy looked to Wyatt for guidance.

“He asked you your name,” Wyatt said.

It occurred to Wyatt that in the time they’d spent in the boy’s company, neither he nor any of his men had bothered to ask that question. They’d simply addressed him as “lad” or “son” or, in Donaldson’s case, “young ’un”. Though they all knew the name of the damned dog.

The boy stared at Tewanias and then at each of the Rangers in turn. It was then that Wyatt saw the true colour appear in the boy’s eyes. Blue-grey, the shade of rain clouds after a storm.

The boy drew himself up.

“My name is Matthew,” he said.

1

Albany, New York State, December 1812

BEWARE FOREIGN SPIES & AGITATORS!

The words were printed across the top of the poster, the warning writ large for all to see.

Hawkwood ran his eye down the rest of the deposition. Not much had been left to the imagination. The nation was at war, the country was under threat and the people were urged to remain vigilant at all times.