Полная версия

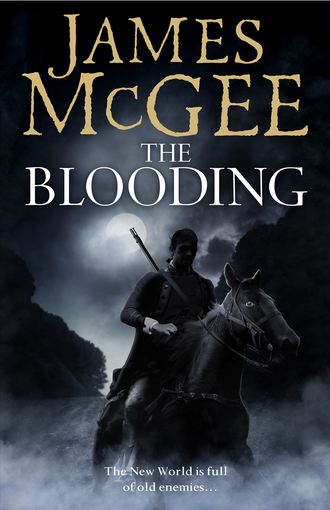

The Blooding

The clerk had referred Hawkwood to the wall behind his counter, upon which was suspended, to use the clerk’s own description, ‘this most excellent map by Mr Samuel Lewis of Philadelphia’. Following the clerk’s finger, Hawkwood had seen that both roads were clearly defined.

Two choices, then, Hawkwood thought as he folded his own map away. Remain in Albany until the northern post road was passable, which could turn out to be a very long wait; or try the ferry route. If he chose the latter, at least he’d be on the move and heading in the right direction.

Johnstown.

The name continued to hover at the corner of his mind, like an uninvited guest hidden behind a half-opened door. Hawkwood pushed the memories away, back into the shadows, forcing himself to concentrate on the more pressing task in hand.

The jetty for the local ferries lay at the end of the steamboat quay. It struck Hawkwood as he set off that the clerk had failed to mention the steamboat when giving him his directions. Hawkwood assumed that was because Albany and not Troy was the vessel’s terminus. Either that or the clerk had a questionable sense of humour and had wanted Hawkwood to get the shock of this life if and when the damned thing turned up and he was in the vicinity.

In which case, the plot had worked.

It was a pity Nathaniel Jago wasn’t here, Hawkwood reflected. His former sergeant and staunch ally, who’d protected his back from Corunna to the slums of London’s Ratcliffe Highway, would certainly have had something to say on the matter, even if it was only to remark that they were both a bloody long way from home.

And even as that thought crossed his mind, there rose within him the reality that the statement would only have been half. For Hawkwood was probably closer to home now than he had been at any time in the last thirty years.

Johnstown.

The slow clip-clop of iron-shod hooves and the creak of an ungreased axle came from behind. Hawkwood stepped aside to allow the vehicle room.

It was as he glanced up that he became aware of the expressions on the faces of the people around him. Some appeared curious; others strangely subdued, while a few displayed a more unfathomable expression which could have been interpreted as sympathy. Intrigued, Hawkwood followed their gaze.

It took him a moment to realize what he was seeing.

Of the dozen or so uniformed men seated or slumped in the back of the mud-splattered wagon, more than half wore their tunics in full view while the rest wore theirs beneath shabby greatcoats. All were bare-headed save for a couple sporting black shakos. The ones whose heads were not bowed gazed about listlessly, their pale, unshaven faces reflecting the resignation in their eyes.

It was not the sight of their drawn features that caused Hawkwood’s throat to constrict, however. It was the colour of their jackets. Stained with dirt and sweat they may have been, but there was no hiding their scarlet hue.

The men in the wagon were British redcoats.

As if the uniforms weren’t sufficient evidence, the mounted officer and the six-man escort marching to the rear of the vehicle and the manacles the red-coated men were wearing left little doubt as to their identity and status.

As prisoners.

A voice called out from the onlookers.

“Who’ve you got there, Lieutenant?”

The mounted officer ignored the enquiry and kept his eyes rigidly to the front. The last man in the escort line was not so reticent.

“You blind?” he muttered sarcastically from the corner of his mouth. “Who d’you think they are?”

Emboldened, the questioner tried again. “So, where’re you taking ’em then? Home for supper?”

Someone laughed.

The wagon halted. The lieutenant rode his horse past the head of the vehicle. As he dismounted and entered the ferry office, the less reclusive trooper, cocky at having been nominated the fount of all knowledge, jerked a thumb at the landing stage. “Ferrying ’em to Greenbush. They’ll be quartered in the guard house before we move ’em on to Pittsfield.”

“Where’ve they come from?” a man standing near to Hawkwood asked.

The soldier sniffed and shrugged. “Don’t rightly know. I heard they were taken near Ogdensburg. We’ve only been with ’em since Deerfield. We’d’ve had to march the bastards if the lieutenant hadn’t commandeered the wheels.”

“Don’t look much, do they?” someone muttered in an aside.

You wouldn’t either, Hawkwood thought, if you’d had to march most of the way from Ogdensburg and then been shackled to the back of a bloody prison cart.

Hawkwood had no idea which British regiments were serving on the American continent and he wasn’t close enough to the wagon to get a good view of the insignia, though the green facings on a couple of the tunics suggested their wearers might have been from the 49th, the Hertfordshires, while the red facings could have represented the 41st Regiment of Foot.

The lieutenant returned. “All right, Corporal! Move them down to the landing. You can board the ferry when ready.”

As the driver released the brake and flicked the reins to nudge the horses forward, the escort shouldered their muskets.

“Here we go,” the talkative one murmured.

The novelty over, the spectators began to drift away and Hawkwood looked towards the men on the wagon. Pittsfield was, presumably, the nearest prison of any note where captured enemy were being held.

His eyes roamed over the tired faces, seeing in them the worn expressions of men who’d come to accept their personal defeat. Two or three looked to be half asleep; either that or they’d chosen to feign exhaustion as a means of avoiding the stares of onlookers and of exhibiting fear in the face of their captors.

The wagon jerked into motion. As it did so, one of the greatcoat-clad soldiers shifted position. Until then, his features had been concealed by the coat’s upturned collar. As he turned, his face came more into view.

Had Major Quade not mentioned Fulton by name, causing Hawkwood to revive memories of Narwhale and the events surrounding William Lee’s assassination plot, the mere turning of the prisoner’s head might not have amounted to anything.

Except …

It took a second or two and even then Hawkwood didn’t really believe it. But as he stared at the wagon’s occupants, the man in the greatcoat looked up. At first, there was no reaction; the soldier’s gaze moved on. And then stopped. It was then that Hawkwood saw it; the slight moment of hesitation before the prisoner’s face turned back. In a movement that would have been imperceptible to those around him, Hawkwood saw the soldier’s eyes fix on his and widen in mutual recognition.

And, immediately, Hawkwood knew that every move he’d been planning had just been made redundant.

2

May 1780

Tewanias led the way, with the Rangers and the boy following in single file behind. The dog kept pace, sometimes running on ahead, at other times darting off to the side of the trail, nose to the ground as it investigated interesting new smells, but always returning to the line, tongue lolling happily and tail held high as if the journey were some kind of game.

They walked the horses, letting the beasts set their own pace. Save for the occasional bird call, the woods were dark and silent around them. Talk was kept to a minimum. The only other sounds that marked their progress were the rhythmic plod of hooves on the forest floor and the soft clinking of a metal harness.

Every so often, a rustle in the undergrowth would indicate where a startled animal had broken from cover. At each disturbance the Indian and the Rangers and the boy would rein in their horses and listen intently but thus far there had been no indication that they were being followed.

As they rode, Wyatt thought back to the events that had taken place at the cabin, only too aware of how fortunate they’d all been to have emerged from the fight without suffering so much as a scratch, though it had been clear that the Committee members, having been taken completely by surprise, had possessed neither the discipline nor the instinct to have affected an adequate defence, let alone a counter-attack. Save, that is, for the one who’d somehow come back to life and shot Will Archer. Despite Wyatt’s attempts to erase it, the nagging thought persisted:

If we’d checked the bodies, Archer would be alive. Maybe.

It was small comfort knowing that by opening fire on the Citizens’ Committee, the farmer had been the one who set in motion the gun battle that had left eight people dead in almost as many minutes, having acted intuitively and in self-defence.

Wyatt’s mind kept returning to the expression on the boy’s face when Ephraim Smede had fallen to the ground, the hatchet embedded in his back. There had been no fear, no contrition or revulsion; no regret at having killed a man. Neither had there been satisfaction or triumph at having exacted restitution for the deaths of his aunt and uncle. Instead, there had been a calm, almost solemn acceptance of the deed, as if the dispatching of another human being had been a task that had to be done.

Only when he’d seen his uncle lying mortally wounded in Wyatt’s arms had the boy’s expression changed, first to tearful concern, followed swiftly by pain and ending in a deep, infinite sadness when he’d looked towards Beth Archer’s body. Even at that tender age he seemed to understand that the balance of his life had, from that moment, been altered beyond all understanding.

Wyatt had accompanied the boy to Beth Archer’s corpse. He’d watched as the child had knelt by her side, taking the woman’s hand in his own, holding it against his cheek. For a moment Wyatt had stood in silence, waiting for the tears to start again, but that hadn’t happened. When he’d laid his hand on the boy’s shoulders telling him that they had to leave and that there were graves to be dug, there had been a brief pause followed by a mute nod of understanding. Then the boy had risen to his feet, jaw set, leaving the Rangers to prepare the burials, while he’d returned to the cabin to gather his few belongings and retrieve the dog.

It wasn’t the first time Wyatt had seen such stoicism. He had fought alongside men who, having survived the bloodiest of battles, had displayed no emotion either during the fight or in the immediate aftermath, only to be gripped by the most violent of seizures several hours or even days afterwards. Wyatt wondered if the same thing was going to happen to the boy. He would have to watch for the signs and deal with the situation, if or when it happened.

The Rangers, partly out of unease at not knowing what to say but mostly because they were all too preoccupied with their own thoughts, had maintained a disciplined silence in the boy’s presence. Wyatt wasn’t sure if that was the best thing to do in the circumstances, but as he had no idea what to say either, he had followed suit and kept his own counsel. Without making it obvious what he was doing, he kept a watchful eye on their young charge. Not that the boy seemed to notice; he was too intent on watching Tewanias. Whether it was curiosity or apprehension at the Mohawk’s striking appearance, Wyatt couldn’t tell. Occasionally, Tewanias would turn in his saddle, and every time he did so the boy would avert his gaze as if he’d suddenly spotted something of profound interest in the scenery they were passing. It might have been amusing under different circumstances, but smiles, on this occasion, were in short supply.

They’d been travelling for an hour before the boy became aware of Wyatt’s eyes upon him. He reddened under the Ranger’s amused gaze. Tewanias was some thirty yards ahead, concentrating on the trail and when the boy had recovered his composure he nodded towards the warrior, frowned and enquired hesitantly: “Your Indian, which tribe does he belong to?”

Wyatt followed the boy’s eyes. “He’s Mohawk. And he’s not my Indian.”

The boy flushed, chastened by the emphasis Wyatt had placed on the word “my”. “Uncle Will said that the Mohawk were a great tribe.”

“The Mohawk are a great tribe.”

The boy pondered Wyatt’s reply for several seconds, wondering how to phrase his next question without incurring another correction.

“Is he a chief?”

“Yes.” Wyatt did not elaborate.

The boy glanced up the trail. “Why does he keep staring at me?”

“Same reason you keep staring at him,” Wyatt said evenly.

The boy’s head turned.

“He finds you interesting,” Wyatt said and smiled.

“Why?”

“Why do you find him interesting?” Wyatt countered.

The boy thought about his reply. “I’ve never been this close to an Indian before.”

“Well, then,” Wyatt said. “There you are. He’s never been this close to anyone like you before.”

“Me?”

“A white boy,” Wyatt said. Thinking, but not voicing out loud: who killed a man with an axe.

The boy fell silent. After several seconds had passed he said, “Why does he paint his face black?”

“To frighten his enemies.”

The boy frowned. He stared hard at the Ranger.

“I don’t need paint,” Wyatt said, “if that’s what you were thinking. I’m frightening enough as it is.”

A small smile played on the boy’s lips.

It was a start, Wyatt thought.

It was close to noon when the woods began to thin out, allowing glimpses of a wide landscape through gaps in the trees ahead. Wyatt trotted his horse forward to join Tewanias at the front of the line.

“Stand! Who goes there?”

The riders halted. Two men stepped into view from behind the last clump of undergrowth before the trees gave way to open ground. Wyatt surveyed the red jackets, muddy white breeches, tricorn hats with their black cockades and muskets held at the ready. The uniforms identified the men as Royal Yorkers; the colonel’s regiment. Wyatt knew that Tewanias would have detected the duo from a long way back. Indeed, he’d have done so even if the men had been dressed in leaf coats and matching hoods, but there had been no need to give a warning. The Mohawk had known that the soldiers posed no threat.

Good to know the piquets are doing their job, Wyatt thought. Though what the troopers would have done if the returning patrol had turned out to be of Continental origin was unclear. Fired warning shots and beaten a hasty retreat, presumably, or stayed hidden until they’d passed and then sounded the alert.

He addressed the soldier who’d given the order. “Lieutenant Wyatt and party, returning from a reconnaissance. Reporting to Captain McDonell.”

The corporal ran his eye around the group, noting the hard expressions on the unshaven faces. His gaze did not falter when it passed over Tewanias, but flickered as it took in the boy, who looked decidedly out of place among his fellow riders.

“That your hound, Lieutenant?” The corporal jerked his chin towards the dog, which was sniffing energetically at his companion’s gaiters.

“Best tracker in the state,” Wyatt said.

“That so?” The corporal regarded the dog with renewed interest. “What’s his name?”

“Sergeant Tam.”

The corporal gave Wyatt a look. “Well, when the sergeant’s stopped sniffing Private Hilton’s crotch, sir, you’ll find the officers down by the main house.”

Wyatt hid a smile at the trooper’s temerity. “I’m obliged to you. Carry on, gentlemen.”

Raising knuckles to their hats, the two piquets watched as the men and the boy rode on.

Private Hilton hawked up a gobbet of phlegm, spat into the bushes and cocked an eyebrow at his companion’s boldness in the face of a senior rank. “Sergeant Tam?”

The corporal shrugged. “Wouldn’t bloody surprise me. You know what Rangers are like.”

Private Hilton sniffed lugubriously. “Scruffy beggars, that’s what. If they’ve given the dog stripes, wonder what rank they’ve given the Indian?”

The corporal, whose name was Lovell, pursed his lips. “I heard tell some of ’em have been made captains, but if you want to ask him, be my guest.”

Private Hilton offered no reply but scratched his thigh absently, his nose wrinkling in disgust as his hand came away damp. Wiping dog slobber from his fingers on to his uniform jacket, he shook his head.

“Bleedin’ officers,” he muttered.

Quietly.

Emerging from the treeline, Wyatt reined in his horse and stared out at a rolling countryside punctuated with stands of oak, pine and hemlock. The estate was spread across the bottom of the slope. It covered a substantial area, comprising barns, storehouses, workshops, grist and saw mills, a smithy and several cottages, and could easily have been mistaken for a small, peaceful village had it not been for the tents and uniformed troops gathered at its heart.

One building, set apart from the others by virtue of its size and architecture, caught the eye. Sheathed in white clapboard, and with leaf-green shutters, the mansion, which was built on a slight rise, was protected at the front by a circle of yellow locust trees and at the rear by two enormous stone blockhouses.

As they approached the camp perimeter, Wyatt’s attention was drawn towards several dark smudges moving slowly across the south-eastern horizon. The plumes of smoke were too black and too dense to be rising from cooking fires. Somewhere, off beyond the pinewoods, buildings were ablaze. As he watched, more drifts began to appear, like lateen sails opening to the wind. The fires were spreading. For a second he thought he could smell the burning but then, when his nose picked out the scent of coffee, he knew the aromas were emanating from the field kitchen that had been set up in the lee of one of the blockhouses.

In the camp itself, all appeared calm. There were no raised voices; no officers yelling orders, putting the men through their drills. There was, however, no hiding the purposeful way the soldiers were going about their business or the sense of readiness that hung in the air. There were no musket or rifle stands. Every man carried his weapon to hand in case of attack. Wyatt glanced towards the boy who, to judge from the way his eyes were darting about, was overawed by the appearance of so many troops.

A peal of girlish laughter came suddenly from Wyatt’s right. He turned to where half a dozen children were engaged in a game of chase on the lawn beneath the trees. A knot of adults, all dressed in civilian clothes, was keeping a close watch on the high spirits; families who’d made their own way or who’d been delivered to the Hall by the other patrols. Wyatt wondered if their numbers had swelled much since he’d left.

Standing off to one side was a group of two dozen Negroes, of both sexes, some with children in hand. Servants and farm workers, either collected from the surrounding districts or who’d arrived at the Hall of their own volition in the hope of joining the exodus.

Halting by the first blockhouse, Wyatt and the others dismounted and secured their mounts to the tether line.

“Wait here,” Wyatt told the boy. “Keep your eye on the horses and make sure Tam stays close. Don’t let him run off, else he’ll end up in one of their stews.” He jerked a thumb at a dozen Indian warriors who were gathered around a circular fire pit above which a metal pot was suspended from a tripod of wooden stakes.

The boy’s eyes widened.

“It was a jest, lad,” Wyatt said quickly, smiling.

Behind him, he thought he heard Tewanias mutter beneath his breath.

“Best keep him near, anyway,” Wyatt advised, indicating the dog. “We won’t be long.”

To Donaldson, Wyatt said quietly, “Look after them. I’m off to report to the captain.” He turned away, paused and turned back. “See if one of you can rustle up some victuals. And some coffee. Strong coffee.”

Leaving the others, Wyatt and Tewanias, long guns draped across their arms, made their way to the group of officers gathered around a table strewn with papers that had been set up on the grass close to the mansion’s rear entrance.

As Wyatt and Tewanias approached, a green-coated officer glanced up and frowned.

“Lieutenant?”

“Captain.” Wyatt tipped his cap.

As the officer straightened, Tewanias moved to one side, grounded his musket and rested his linked hands on the upturned muzzle. He looked completely at ease and unimpressed by the ranks that were on display.

Captain John McDonell glanced over Wyatt’s shoulder towards the tether line. He was a tall man; gangly and narrow-shouldered with a thin face and a long nose to match. A native of Inverness, with pale features and soft Scottish lilt, McDonell always reminded Wyatt of a schoolmaster. The captain’s bookish appearance, however, was deceptive. Prior to his transfer to the Rangers he’d seen service with the 84th Regiment of Foot and had survived a number of hard-fought engagements, including St Leger’s expedition against Fort Stanwix. He’d also helped defend British maritime provinces from Colonial attacks by sea and on one memorable occasion had led a boarding party on board an American privateer off Lunenburg, Nova Scotia, capturing the ship and crew and delivering them into Halifax in chains.

“Who’ve you got there?” McDonell asked.

“Name’s Matthew,” Wyatt said.

The captain nodded as if the information was only of passing interest and then he frowned. Something in the equation was missing, he realized. He turned his attention back to the Ranger. “Where’s his family?”

Wyatt’s expression told its own story.

McDonell sighed. “All right, let’s hear it.”

“We ran into some opposition,” Wyatt said.

Behind McDonell, the officers gathered around the table paused in their discussion.

Instantly alert, McDonell’s chin lifted. “Regulars or militia?”

Wyatt shook his head. “Neither. Citizens’ Committee.”

McDonell’s eyebrows rose. “Really? I’d not have taken them for a credible threat.”

“They weren’t,” Wyatt said.

Pondering the significance of Wyatt’s terse reply, the captain waited expectantly.

“Turns out they were on an incursion of their own. We interrupted them.”

“Go on.”

“We were at the Archer farm,” Wyatt said. “We—”

“Did you say Archer?”

The interjection came from behind McDonell’s left shoulder. A bewigged, aristocratic-looking officer dressed in a faded scarlet tunic stepped forward.

Wyatt turned, remembering to salute. “Yes, Sir John. William Archer. We were tasked to bring him to the Hall. His homestead is … was … on the other side of the Caroga.”

Colonel Sir John Johnson matched McDonell for height but where the captain was thin the colonel was well set, with a harder, fuller face. His most prominent features were his dark blue eyes and his beaked nose, which gave him the appearance of a very attentive bird of prey.

“My apologies, Colonel,” McDonell said quickly. “Allow me to introduce Lieutenant Wyatt; 4th Ranger Company.”

“Lieutenant.” The colonel’s gaze flickered sideways towards Tewanias before refocusing on the Ranger.

“Colonel,” Wyatt said.

“You said you were at what was the Archer homestead.”

“I regret that both William Archer and his wife were killed in the exchange, Colonel.”

A look of pain crossed the colonel’s face. His eyes clouded. “Tell me,” he said.

The two officers listened in silence as Wyatt recounted the events of the morning.

“Bastards!” McDonell spat as Wyatt concluded his description of the skirmish. “God damned bloody bastards!”

The colonel looked towards the boy.

“He’s Archer’s nephew,” Wyatt said.

Sir John said nothing for several seconds and then turned back. He shook his head wearily and sighed. “No, actually, he isn’t.”

“He referred to Archer as his uncle,” Wyatt said, confused.

The colonel’s expression softened. “For the sake of convenience, I dare say. Though, I’ve no doubt that’s how he came to look upon them.”