Полная версия

The Wood for the Trees: The Long View of Nature from a Small Wood

It is easy enough to convert diameters into circumferences, and with my very own trees the latter is what I record at shoulder-height with my tape measure. I can prove that many of the standing beeches are of similar size to those sitting on the log pile. It is actually rather easy to show this without wielding the tape, by using that alternative, hippy measurement – ‘the hug’. Trees with a fifty-centimetre diameter can be comfortably hugged, with hands meeting around their girth. There are an equal number of trees that are just too big to hug, although they do decrease in diameter to become huggable towards the canopy. And then there are the real giant trees, like the King Tree and the Queen Tree, and one I call the Elephant, with circumferences up to 250 centimetres. Surely these are much older than eighty years. If I assume that they continue to grow by adding a three-to-four-millimetre ring every year, it is not unreasonable to arrive at an age of 140 to 180 years. There are perhaps a dozen of these trees scattered through our wood. Their bark eventually loses the smoothness of the younger trees to become lightly scarred, as if daubed with vertical stretch-marks. Since there are certainly no trees still more antique, I conclude that these fine examples have been responsible for seeding some of their younger companions. They have been left alone. A great felling must have occurred about eighty years ago – and selective felling probably continued for another twenty years or so until Sir Thomas Barlow’s ownership, when we know that little happened in our part of the wood. The somewhat ‘unhuggables’ may well record regrowth after another, earlier phase of beech harvesting. There is no doubt at all that the whole wood has been replaced, thinned, sawn and regenerated. Its history is written in the tree rings. This is the same wood that John Stuart Mill walked through in 1828. Only the trees have changed.

Like those of many wind-pollinated species, beech flowers are unspectacular. I already noticed brown bunches of fallen stamens from the male flowers in May, while the separate female components now sit above, waiting to mature into three-sided beechnuts, which will eventually fall to the ground in October. The most beautiful and accurate drawings I know of living twigs are by Sarah Simblet in The New Sylva,2 which is a large, luxurious, even sumptuous tribute to John Evelyn’s original, and about as appropriate for taking into a real wood as The Oxford English Dictionary. Last year’s beechnuts germinate as early as April, and the seedlings can be told from all others by their pale-green seed leaves (cotyledons), which resemble the blades of two inch-wide ping-pong bats placed side by side. Before the canopy has opened out, optimistic seedlings can come up almost anywhere in the beech litter, and are not short of light. A tender shoot then appears between the two seed leaves and starts to put out regular leaves. By now in June it is already clear that most of these young plants are doomed; they lack enough light to make further progress, as the canopy sucks it all up to feed the crowns of the trees. The babies yellow and fade. Only those seedlings close to a clearing can put on the vital first inches of growth that will give them a chance to mature into a giant. That is where a dozen or so small beech trees not much taller than I am vie to be first to fill the gap in the sky. At some stage I will have to pick a winner and thin out the rest. If I fail to do so the surviving trees will become too crowded and grow all spindly.

Squirrels

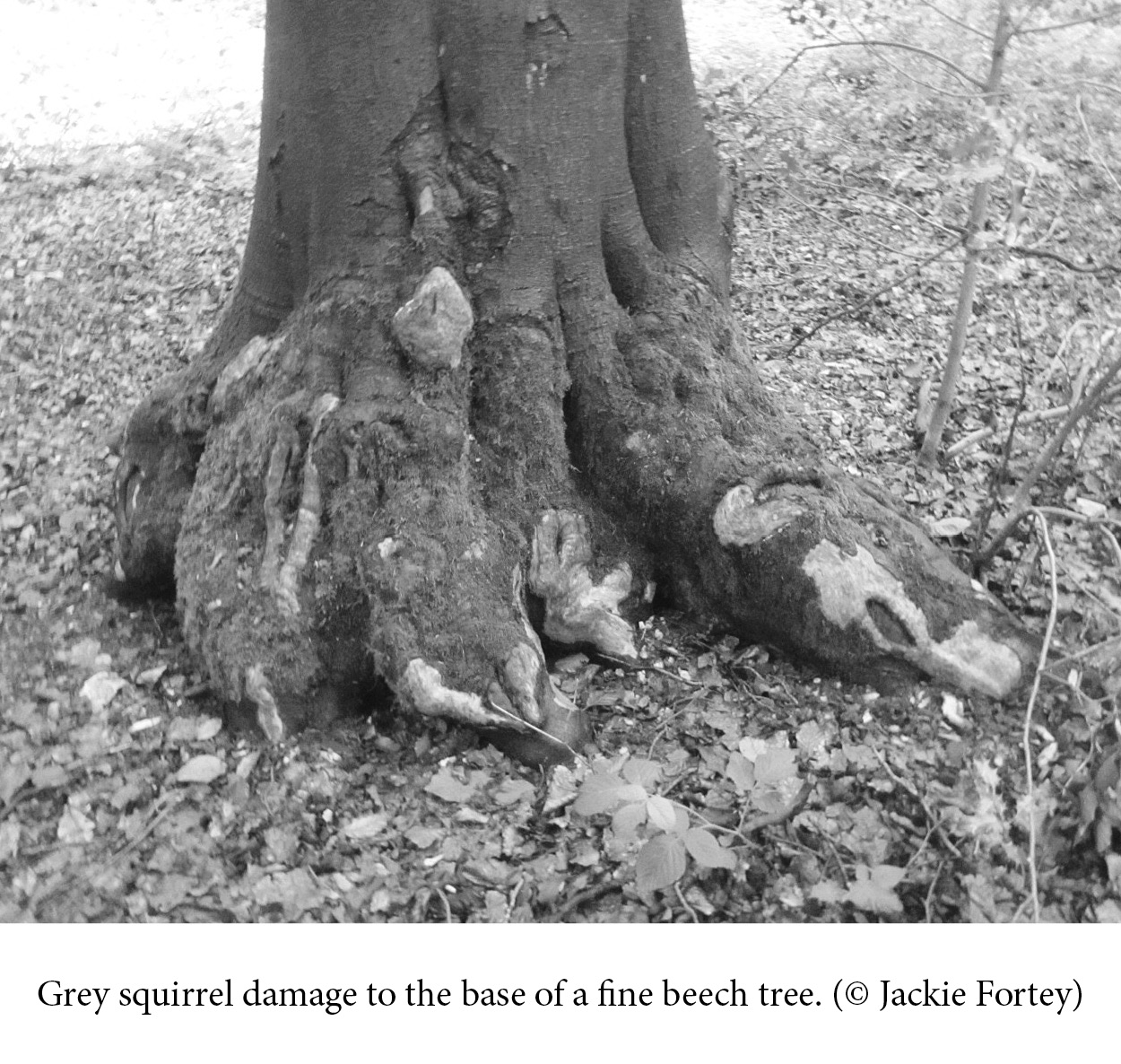

I am sitting in contemplative mood on a beech log left behind by cousin John when the bombardment begins. I cannot work it out at first. Bits of hard stuff are falling from the sky, and some of them are hitting me. Then I catch a piece as it lands: it’s a fragment of beech bark, more than a quarter of an inch thick. I am being pelted with beech bark! Protecting my eyes with spread fingers I look for the source of the onslaught. Perhaps forty feet above me a horizontal beech branch leans out from the nearest trunk. I catch a glimpse of something grey and fuzzy moving about on top of the branch. Then a squirrel peeps momentarily over the edge and identifies itself; it is not worried for its safety – it is only concerned about lunch. It is obviously not eating the beech bark; it is throwing it at me instead. He is after the sugary spring sap still flowing beneath the bark. Like one of the regulars in the Maltsters Arms, he is having a liquid lunch. The bark is stripped and the layer underneath it licked clean. It is obviously damaging to the tree. Now I notice that the bole of a nearby beech – and not a small one, either – displays a raw wound. A patch of bark has been removed, and the sapwood is on display, all yellow and unnaturally bright. Several other trees around me show the same feature, always close to the roots. In my absence, the squirrels have been picnicking al fresco.

This arboreal dining habit explains a feature I have noticed on fallen beech branches. Many of them have the bark stripped from the upper side; this is less obvious than on new wounds because the colour contrast has dulled with the passage of time. Bark on the undersides of the branches is protected from squirrel activity, so seen from the ground branches high above look just fine. In fact, many are damaged on top, and perhaps this encourages them to fall before their time.

Another chip of bark whizzes past my ear. I could almost hear a snicker from far above. Re-examining the chewed boles of the beech trees I see yet more evidence of old scars. Fortunately there is enough bark left to allow the big trees to survive. Nor is all well with some of my young beeches. Many of those with trunks thicker than my arm have been mutilated in a similar way. A few trees of middling size – forty years old perhaps – have become grotesquely distorted, their crowns twisting like corkscrews, branches all whiskery and set akimbo like broken limbs. I had not known what to make of them before. Squirrel damage has stunted and deformed them. ‘Little bastards,’ I growl, but that hardly seems adequate for an animal that may be affecting beech regeneration that has hitherto endured in the Chiltern Hills for a thousand years.

There are always grey squirrels somewhere in the wood. They skitter acrobatically along branches and leap effortlessly through the canopy; it is their realm. They build untidy drays high in the trees in which they can raise two litters a year. They have abundantly fluffy tails. They are, of course, invaders from North America. They were released on a few English estates in the nineteenth century for aesthetic reasons, and then stayed on and prospered. They pushed out the red squirrels from most of England, and continue to expand their range northwards into Scotland today: they are bolder animals, faster breeders and generally more robust. They carry a lethal pox virus to which their red cousin has not yet acquired immunity. There is nothing new about worrying about the invader. A wartime Surrey Mirror exclaimed in 1942 that to eradicate this pest ‘all possible steps such as shooting and trapping must be taken. The national interest demands it.’ Never mind Hitler: the nation might be brought down by a climbing rodent! When I was a youngster there was a bounty of sixpence on every grey-squirrel tail. Neither threats nor inducements have worked: the cheeky grey squirrel dances nimbly onwards.

It has been claimed that red squirrels are better adapted to conifer woods and that greys outcompete them only elsewhere – though I know plenty of conifer plantations with greys in command. I try very hard to banish Beatrix Potter’s charming Tale of Squirrel Nutkin from my mind, since her drawings provide such effective propaganda for the red species. Some ecologists even challenge the notion of ‘native’ species at all, when so much British wildlife has come from elsewhere. They are probably right that it is foolish to think of restoring some notional Eden, a prelapsarian paradise labelled ‘Natives Only’. In this argument I am obliged to take the part of my precious beech trees. Although I can find some records of tree damage by red squirrels, it does not seem to be as extensive as that caused by the grey interloper. A proven continuity of fine beech woods in our patch points to the red squirrel as no more than an occasional nuisance. Maybe they were once popular enough as food to keep the numbers down. Most damage happens in years when lots of squirrels have come through a mild winter following a good year for beech mast: overpopulation is part of the problem. One of my woody neighbours shoots as many greys as he can; another believes nature will correct the numbers in her own good time.

I have found a bleached squirrel skull to add to the collection, manner of death uncertain. I simply want to believe that there will still be tall, healthy beech woods here in the century to come, so that some future J.S. Mill may glory in their abundance. In the end, global warming might be more important than any kind of squirrel. The New Sylva warns that if summer drought increases, beech ‘may disappear from the Chiltern Hills except on northern slopes with moist soils’. To survive at all, the woods will have to move northwards, alongside the delinquent greys. They will become partners in a human crime. I shudder at the thought.

Two ghosts and a Dutchman’s pipe

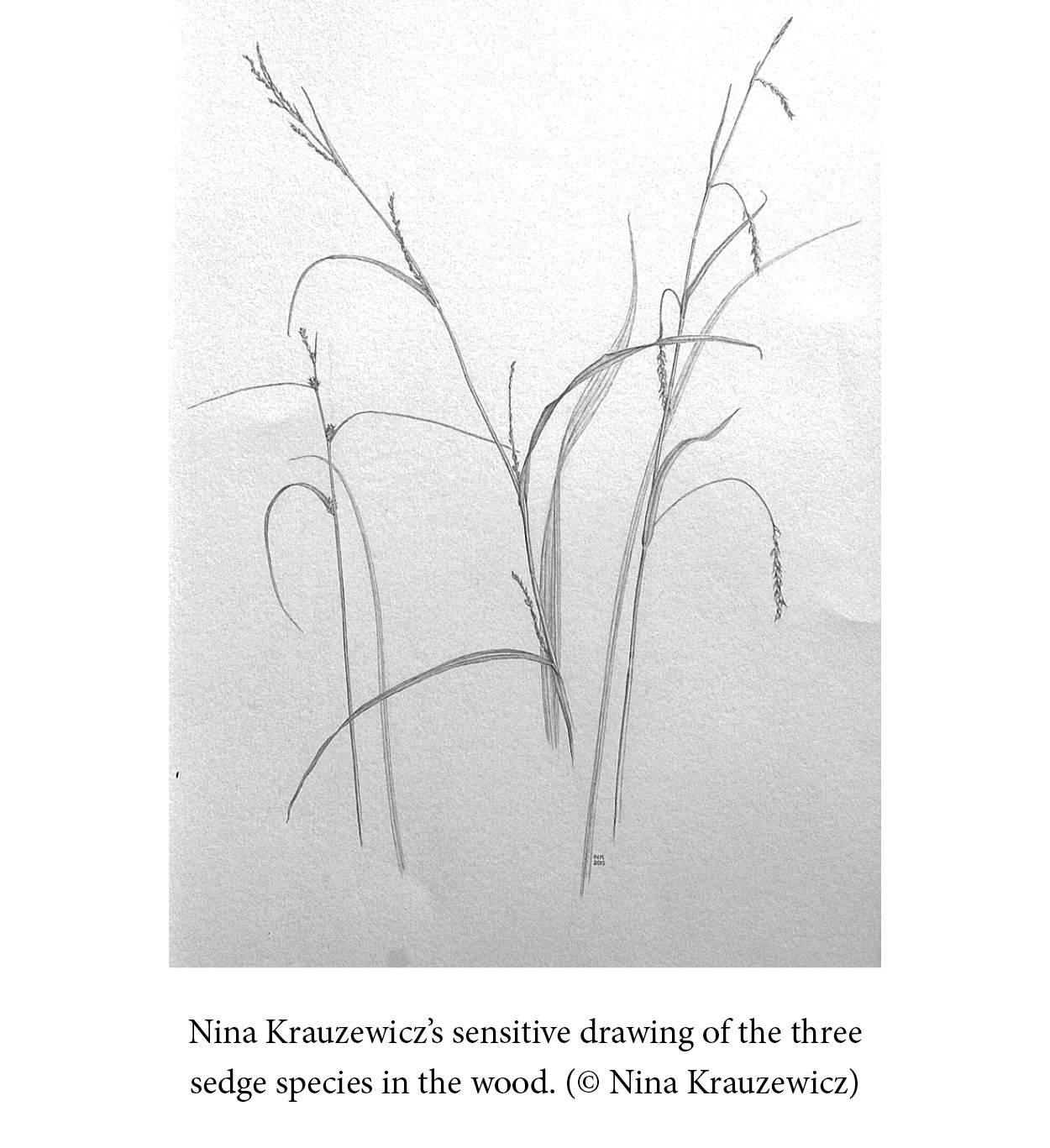

When the beech canopy captures the sun the forest floor becomes a darker place. The bluebells have faded, and only faint greasy traces reveal the wraiths of their dead leaves. The grasses that made a brief, bright sward are muted now; nodding wood melick has set its seed for the year and will soon aspire to invisibility. Taller, elegant wood millet (Milium effusum) raises its flowering spike in wispy tiers making a brief show of green flowers that dangle from the ends of spread branchlets like tiny beads. Only sedges by the wayside are more obdurate. Their tufts and clumps of coarse, dark-green leaves see out the seasons, though few passers-by would notice them if there was the bright promise of bluebells in the woods beyond. Wood sedge (Carex sylvatica) briefly dangles little rods dotted with yellow stamens in spring, and then might even be described as pretty.

Its broader-leaved companion, thin-spiked wood sedge (Carex strigosa), is a recherché plant for botanical enthusiasts, with flower spikes so discreet that I can only identify the species with a lens in one hand and a book in the other. It is something of a rarity, though it seems to grow enthusiastically enough in ruts left by tractors. Distant sedge (Carex remota), with the thinnest leaves of all our sedges, lurks inconspicuously by the damp seep, and has its greenish fruits tucked into its leaf bases, so that anyone giving it a casual glance would think it a grass. Toughness in sedges is evidently inversely proportional to their showiness. But even they cannot grow under the largest beeches. Apparently, nothing can. The deepest leaf litter is inimical to living things. It is a place fit only for ghosts.

The rarest plant in Britain is such a ghost: the ghost orchid (Epipogium aphyllum).3 It disappears like a phantom and then conjures a new haunting in a new wood. It has been declared extinct, and then spookily reappeared, even after decades. It is a spectre much sought by botanists; some plant-hunters develop an obsession with its rediscovery. And it made one of its few and unexpected appearances in Lambridge Wood. Ninety years ago a young Henley woman called Eileen Holly found it in deep litter where nothing else will grow. It appeared from 1923 until 1926. A lively eyewitness account from a prolific botanical diarist, Eleanor Vachell, leaves no doubt about the drama of the discovery – even though it reports the ghost of a ghost:

28 May 1926. The telephone bell summoned Mr. [Francis] Druce to receive a message from Mr. Wilmott of the British Museum. Epipogium aphyllum had been found in Oxfordshire by a young girl and had been shown to Dr. [George Claridge] Druce and Mrs. Wedgwood. Now Mr. Wilmott had found out the name of the wood and was ready to give all information!!! Excitement knew no bounds. Mr. Druce rang up Elsie Knowling inviting her to join the search and a taxi was hurriedly summoned to take E.V. [Eleanor Vachell] and Mr. Druce to the British Museum to collect the particulars from Mr. Wilmott. The little party walked to the wood where the single specimen had been found and searched diligently that part of the wood marked in the map lent by Mr. Wilmott but without success, though they spread out widely in both directions … Completely baffled, the trio, at E.V.’s suggestion, returned to the town to search for the finder. After many enquiries had been made they were directed to a nice house, the home of Mrs. I., who was fortunately in when they called. E.V. acted spokesman. Mrs. I. was most kind and after giving them a small sketch of the flower told them the name of the street where the girl who had found it lived. Off they started once more. The girl too was at home and there in a vase was another flower of Epipogium! In vain did Mr. Druce plead with her to part with it but she was adamant! Before long however she had promised to show the place to which she had lead [sic] Dr. Druce and Mrs. Wedgwood and from which the two specimens had been gathered. Off again. This time straight to the right place, but there was nothing to be seen of Epipogium!

2 June 1926. A day to spare! Why not have one more hunt for Epipogium? Arriving at the wood, E.V. crept stealthily to the exact spot from which the specimen had been taken and kneeling down carefully, with their fingers they removed a little soil, exposing the stem of the orchid, to which were attached tiny tuberous rootlets! Undoubtedly the stem of Dr. Druce’s specimen! Making careful measurements for Mr. Druce, they replaced the earth, covered the tiny hole with twigs and leaf-mould and fled home triumphant, possessed of a secret that they were forbidden to share with anyone except Mr. Druce and Mr. Wilmott.4

It is a measure of the allure of this botanical will o’ the wisp that even a cut stem provoked such delight. The flower in person might have induced a serious attack of the ghostly vapours. It is a pretty enough plant, with a few, quite large blooms for a European orchid, each with a pleasingly pinkish spur and yellower sepals. It is fragrant, and probably insect-pollinated. But the plant has no leaves. It has no green on it anywhere. It consists only of a flower spike and the ‘tuberous rootlets’, or ‘coral-like rhizome’, as V.S. Summerhayes described it in Wild Orchids of Britain5 (this led to an alternative common name of ‘spurred coral root’). The scientific species name aphyllum even means ‘without leaves’. Since the flowers blend almost perfectly with beech leaves as a backdrop it is little wonder that they so readily escape detection: it’s a ghost in camouflage. It seems to be an impossible plant, because it has no chlorophyll to manufacture vital proteins and sugars. It clearly does not need light; it can grow in deepest shade where no other plant flourishes. In my old copy of Summerhayes, the author attempted to solve the mystery by allowing the ghost orchid to get its nutrients ‘already manufactured’ from ‘the humus of the soil, which consists of numerous more or less decayed parts of plants and also animals’; in other words, to grow like many fungi – which never have chlorophyll. The story is much more nuanced than that, although mushrooms do indeed play a part, as we shall see.

After Eleanor Vachell’s visit the orchid vanished from Lambridge Wood. Stirring up its rhizome would not have helped. Joanna Cary, who lived nearby and was wont to wander in Lambridge as a child, tells me that in the 1950s she used to avoid crossing paths with funny men in gaiters up in the deep woods, and assumed they were flashers, or worse still, burying something unspecified. It was probably Mr Summerhayes and his eminently respectable band of ghost-hunters. Another local plant enthusiast, Vera Paul, continued the botanical tradition by finding Epipogium at a site just a couple of miles away, sporadically, for over thirty years until 1963. I have seen a drawing of the famous plant framed on the wall at her former house in Gallowstree Common. More recently, the orchid disappeared completely for more than twenty years, until a remarkably persistent ghost-pursuer, Mr Jannink, rediscovered a small example in 2009 in one of its old sites near the Welsh border, far, far away from the Chiltern Hills.6 The ghost orchid is not extinct in Britain after all. However, nothing I have read explains how a plant with such minute seeds can apparently jump so dramatically from place to place. There is something almost spooky about it.

Another ghost haunts Lambridge Wood. Nobody has actually seen it, but I am assured its presence has been felt. After dodging the ‘dodgy’ gentlemen, Joanna Cary also avoided ‘the murder cottage’. Nowadays, it is a pretty house adjacent to the barn at the very edge of our wood, but its reputation must have lingered on for decades. As the Henley Standard reported at the time: ‘Friday, December 8th 1893 will always be regarded as a black day in the annals of Henley history.’ The body of the thirty-year-old housekeeper who looked after the farmhouse, Miss Kate Dungey, was found in the woods a few yards from the door with ‘a terrible gash in the left side of the neck, and a number of wounds about the head’.

It was quite the shock headline of the day; the gruesome story was reported prominently as far away as New Zealand. It had all the right ingredients to impress the public. ‘The spot is as remote and lonely as could possibly be found, and there is very little likelihood of cries for help being heard,’ the Standard reported; and naturally ‘it was a dark and miserable evening’. Miss Dungey was an interesting victim, ‘of good figure, had dark hair, and is said to have been good looking’ – moreover, she was an ex-governess for the children of Mr Mash, fruiterer and owner of the house, so she had the trappings of a gentlewoman. ‘Almost all around Henley knew Miss Dungey and speak well of her,’ the newspaper continued. Could robbery be a motive when ‘nothing had been touched in the house, not even the watch on the sitting room chair’? There were signs of a struggle and blood by the front door, so perhaps the grisly killing took place as the poor woman attempted to flee her assailant. A thick, cherry-wood cudgel discovered by the body may have been involved, but something much sharper caused the deep gash.

Over the next month new evidence emerged, as well as rumours that Miss Dungey had a romantic interest in a local married man, details of which never appeared. By 3 January 1894 one Walter Rathall had been arrested for the crime. He had worked as a labourer on the farm, and led a rackety and irregular life, being at times little more than a tramp. Jackson’s Oxford Journal reported on 13 January that Rathall slept out in the woods all the previous summer – our woods. The paper described how Kate Dungey had advanced him money, which she never recovered, and that ‘he had been discharged principally through the instrumentality of Miss Dungey, with whom he had several quarrels’. Despite an apparent motive, the circumstantial evidence gathered by the police proved insufficient to secure Rathall’s conviction. He walked free; the murder mystery remained unresolved, as it still is to this day.

Hayden Jones, the current occupant of ‘the murder cottage’, tells me a ghost story. On the hundredth anniversary of the murder it was another ‘dark and miserable evening’, though cosy enough inside the house. Hayden relates that the company decided to have a toast to the memory of ‘poor Kate’. As the glasses were raised all the lights in the house were suddenly extinguished – poof! Hayden had previously encountered a definite reluctance on the part of certain woodsmen to enter his premises: a shake of the head and a polite refusal. A presence, they said. It is all nonsense, of course, as every rationalist will agree. Yet, since I heard the story of Miss Dungey, I have been in the wood on an overcast, windy evening late in the year when I heard a sudden brief, distant cry – it must have been a red kite out late, or even a frightened blackbird. And a crunching noise behind the holly bushes was surely just a small, squirrel-weakened branch falling suddenly and noisily to the ground; it is no restless murderer’s shade on the march. Ignore the sudden shiver. Let’s not be silly.

The tortuous saga of the ghost orchid prompts me to make a thorough quartering of Grim’s Dyke Wood in June. It is too much to ask of my tiny piece of ground, I know, but that does not stop me peering closely at every beech-leaf-filled gulley. I will not miss a thing, I tell myself, and for half an hour I trudge like a botanising zombie up and down, up and down. For an instant, my heart stops. Here are two yellow stems arising from the ground and bearing flowers. There is no sign of a leaf, or anything green. So is it an orchid? The stems curve over at their apices like shepherds’ crooks where perhaps half a dozen yellow flowers hang down, almost in the fashion of our bluebells; however, these flowers are tubular. This is not a shape known from any orchid. This may be no ghost, but it still thrills like a sudden, strange apparition. The Red Data List7 records some of the most precious and uncommon species of plants in Great Britain, and this is one of them, in our very own wood! I have known it for many years as an illustration in the Reverend Keble Martin’s indispensable New Concise British Flora. In an even older book I have a list of all the wildflowers I have ever seen, which I have been ticking off since I was a boy: this is one plant that had remained persistently unticked. Nor is it some anonymous, tiny green herb. It is another special plant in the ghost orchid mould lacking all chlorophyll, a spooky spectre, and somehow implausible. It is called the Dutchman’s pipe, or if you prefer, yellow bird’s nest, and by scientists Monotropa hypopitys. I have never met a pipe-smoking Dutchman, but I would now recognise the shape of his favourite accoutrement.

On my hands and knees, I brush away a few loose leaves concealing the bases of the stems of the new discovery. They look a little like blanched asparagus spears, complete with scattered scales. They are the only plants growing in the deep shade. They really do rise straight out of the ground. I would be willing to bet a hundred squirrel tails that if I dug down they would originate from swollen roots such as Eleanor Vachell found for Epipogium. I am not going to try it. A small beetle emerges from one of the flowers, having, I suppose, helped to fertilise it. Over the next few weeks I keep tabs on the small blooms: they last and last. The Dutchman’s pipe is not taking many risks when it comes to setting seed.

Monotropa has recently been the focus of botanical research. In my old edition of Keble Martin – and in many later books – it sits all by itself in its own plant family (Monotropaceae). It seems that no expert could quite make up his or her mind where such a weird, penumbral paradox fitted into the grand scheme of plant evolution. In North America a related, almost supernaturally pallid species is known as the Indian, rather than Dutchman’s, pipe, or sometimes as ‘the corpse plant’ (Monotropa uniflora), which suggests that we are never going to be able to escape the whiff of the graveyard in this chapter. When the techniques of molecular analysis to determine ancestry became widely available it was not long before both species of Monotropa were allied with a much larger plant group, the Ericaceae, the familiar heather (or blueberry) family, with something like four thousand species worldwide. The Dutchman’s pipe was, in its essentials, a heather that had lost everything above ground except the flowers. Now that I study them again, the flowers of Monotropa do indeed recall those of strawberry trees, blueberries or bell heathers – perhaps we should have known all along. Occasionally, science just reinforces common sense.