Полная версия

The Wood for the Trees: The Long View of Nature from a Small Wood

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2016

Copyright © Richard Fortey 2016

The author asserts the moral right to

be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008104696

Ebook Edition © May 2016 ISBN: 9780008104672

Version: 2017-03-17

Dedication

For Eileen and Stuart Skeates

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Map

1: April

2: May

3: June

4: July

5: August

6: September

7: October

8: November

9: December

10: January

11: February

12: March

Picture Section

Acknowledgements

Notes

Index

Also by Richard Fortey

About the Publisher

1

April

After a working life spent in a great museum, the time had come for me to escape into the open air. I spent years handling fossils of extinct animals; now, the inner naturalist needed to touch living animals and plants. My wife Jackie discovered the advertisement: a small piece of the Chiltern Hills up for sale. The proceeds from a television series proved exactly enough to purchase four acres of ancient beech-and-bluebell woodland, buried deeply inside a greater stretch of stately trees. The briefest of visits clinched the deal – exploring the wood simply felt like coming home. On 4 July 2011 ‘Grim’s Dyke Wood’ became ours.

I began to keep a diary to record wildlife, and the look and feel of the woodland as it passed through diverse moods and changing seasons. I sat on one particular stump to make observations, which I wrote down in a small, leather-bound notebook. I was unconsciously compiling a biography of the wood – bio in the most exact sense, since animals and plants formed an important part of it. Before long, I saw that the story was as much about human history as it was about nature. For all its ancient lineage, the wood was shaped by human hand. I needed to explore the development of the English countryside, all the way from the Iron Age to the recent exploitation of woodland for beech furniture or tent pegs. I was moved by a compulsion to understand half-forgotten crafts and revive half-remembered words like ‘bodger’, ‘spile’ and ‘bavin’. Plans were made to fell timber, to follow the journey from tree to furniture; to visit the canopy in a cherry-picker; to explore the archaeology of that ancient feature, Grim’s Dyke, that ran along one side of the plot. I wanted to see if the wood could yield food as well as inspiration.

My scientific soul reawakened as I sought to comprehend the ways that plants and animals collaborate to generate a rich ecology. I had to sample everything: mosses, lichens, grasses, insects, and fungi. I investigated the natural history of beech, oak, ash, yew, and all the other trees. I spent moonlit evenings trapping moths; daytime frolicking with nets to catch crane flies or lifting up rotten logs to understand decay. I poked and prodded and snuffled under brambles. I wanted to turn the appropriate bits of geology into tiles and glass. The wood became a route to understanding how the landscape is forever in a state of transition, for all that we think it unchanging. In short, the wood became a project.

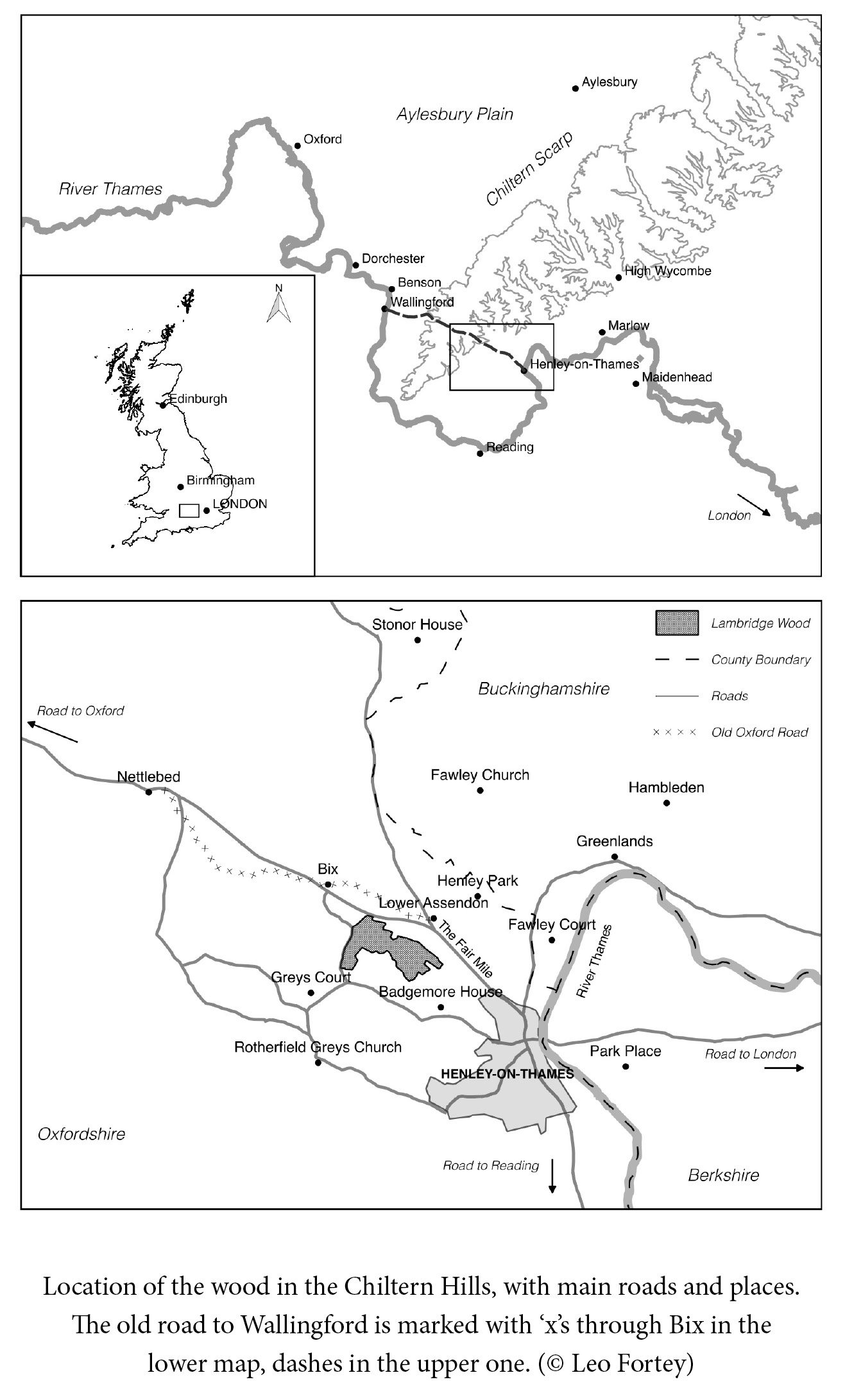

Grim’s Dyke Wood is just a segment in the middle of more extensive ancient woodland, Lambridge Wood, lying in the southern part of the county of Oxfordshire. Splitting Lambridge into separate plots generated a profit for the previous owner, but also allowed people of modest means to own and care for their own small piece of living history. Our fellow ‘woodies’ – as Jackie terms them – proved to include a well-known harpsichordist, a retired professor of business systems, a founder member of Genesis (the band, not the book), a virologist turned plant illustrator, ex-actors turned psychologists, and a woman of mystery. Our own patch is one of the smaller ones. All of the ‘woodies’ have their own reasons for wanting to be among the trees – some desire simply to dream, some would rather like to turn a profit, others to explore sustainable resources. I believe I am the only naturalist. All the owners are there to prevent the wood from being felled or turned into housing. For the long history of Lambridge Wood tells us that our trees are less worked today than at any time in the past. This sad redundancy is no less part of its tale, as our wood is inevitably connected to the wider world of commerce and markets. The histories of my home town, Henley-on-Thames, a mile away, and the famous river on which it sits, are bound into the narrative of the surrounding countryside. Ancient manors controlled the fate of woodlands for centuries. I have to imagine what the wood would have seen or heard as great events passed it by; who might have lurked under the trees, what poachers and vagabonds, poets or highwaymen.

Once the project was under way a curious thing happened. I wanted to make a collection. This may not sound particularly remarkable, but for somebody who had worked for decades with rank after rank of curated collections it was rejuvenation. Life among the stacks in the Natural History Museum in London had stifled my acquisitiveness, but now something was rekindled. I wanted to collect objects from the wood, not in the systematic way of a scientist, but with something of the random joy of a young boy. Perhaps I wanted to become that boy once again. Eighteenth-century gentlemen were wont to have cabinets of curiosities in which they displayed items that might have conversational or antiquarian interest. I wanted to have my own cabinet of curiosity. I would add items when my curiosity was piqued month by month: maybe a stone, a feather, or a dried plant – nothing for the eighteenth-century gent. I believe that curiosity is a most important human instinct. Curiosity is the enemy of certainty, and certainty – particularly conviction that other people are different, or sinful, or irreligious – lies behind much of the conflict and genocide that disfigure human history. If I could issue one injunction to humankind it would be: ‘Be curious!’ My collection will be a way of encapsulating the whole Grim’s Dyke Wood project: my New Curiosity Shop. And I already know that the last item to be curated will be the leather-bound notebook.

The collection requires a cabinet to house it. Jackie and I plan to fell one of our cherry trees and convert it into a wonderful receptacle for the wood’s serendipitous treasures. We must discuss the work with Philip Koomen, a noted Chiltern furniture-maker devoted to using local materials. Philip’s workshop, Wheelers Barn, is in the remotest part of the Chiltern Hills, only about five miles from Grim’s Dyke Wood as the crow flies, but about fifteen as the ancient roads wind hither and thither. His studio is imbued with calm. Polished sections through trees hanging on the walls show the qualities of each variety: colour, texture, grain, and age all combine to distinguish not just different tree species, but individual personalities. No two trees are identical. Some have burrs that section into turbulent swirls. Pale ash contrasts with rich walnut, and cherry with its warm tones is satisfactorily different from oak. This is a man who cares deeply about materials and believes in the genius loci – an integration of human and natural history that lends authenticity to a hand-made item. Philip’s handiwork from our own cherry tree will be a physical embodiment of our wood, but by housing the idiosyncratic collection picked up as the project develops it will also contain the wood, as curated by this writer. It will be a cabinet of memories as much as objects. We haggle a little about design, but I know I shall rely on his judgement. I will have to be patient when I gather up the small things in the wood that take my fancy. It will be some time before the collection can live in its dedicated home.

This book could be thought of as another kind of collection. Extracts from my diary describe the wood through the seasons. I follow H.E. Bates’s wonderful book Through the Woods (1936) in beginning in the exuberant month of April rather than with the calendar year, and frigid January. But then, H.E. Bates himself inherited the same plan from the writer and illustrator Clare Leighton, whose intimate portrait of her own garden through the cycles of the seasons, Four Hedges,1 he much admired. My friends and colleagues come to sample and identify almost every jot and tittle of natural history that they can find. Natural history leads on to science, and the stories of grand estates, woodland skills and trades, and life along the River Thames. Human folly and natural catastrophes link the wood to a wider world beyond the trees. This complex collection explains why the wood is as it is today; its rich diversity of life is a concatenation of particular circumstances. I am trying to reason how the natural world came to be so varied, and my understanding is refracted through the lens of my own small patch. I am trying to see the wood for the trees.

Bluebells

Some trees stand close together, like a pair of friends huddling in mutual support. Others are almost solitary, rearing away from their fellows in the midst of a clearing. The poet Edward Thomas described ‘the uncounted perpendicular straight stems of beech, and yet not all quite perpendicular or quite straight’.2 Each tree trunk has individuality, for all the harmony of their numbers together. One leans a little towards a weaker neighbour; another carries a scar where a branch fell long ago; this one has an extraordinarily slender elegance as it reaches for its place under the sky; that one has a stocky base, as chunky as an elephant’s leg, and doubtless at least as strong. No two trees are really alike, yet their collaboration on the scale of the wider wood creates a sense of architectural design. The relatively pale and smooth beech bark helps to unite the structure, for in the early spring’s soft sunshine the tree trunks shine almost silver. The natural cathedral of the wood is supported by brilliant, vertical superstructure, one that shifts subtly with the moods of the sun.

It is too early in the month for many fresh beech leaves to have unfurled from their tight buds. The wood is still flooded with light. Some of the sunlight falls on the crisp, dark tan to gold-coloured leaves fallen from last year’s canopy that lie in scruffy patches on the ground; stubbornly dry, they have yet to rot away. The sunshine brings the first direct heat of the year, enough to warm our cheeks with hints of seasons to come. Am I imagining that the beech trunk is actually hot on its illuminated side? It does not strain the imagination to envisage the sap rising beneath the grey-green roughened bark, rejuvenated by April showers. Where the sunlight reaches the thin soil spring flowers accept the warmth and light; briefly, it is their time to flourish. After standing to contemplate the grandeur I now have to get down on my hands and knees to see what is happening at ground level. By the pathside are patches of heart-shaped leaves mottled with white; the sun glances off the tiny, glossy, butter-yellow petals of the lesser celandine, eight petals in a circle per flower, not unlike a child’s first drawing of what every flower should be. Celandines are growing in the company of dog violets, whose flowers are as complicated as the celandine’s are simple: the whole borne on an arched-over stem, carrying five blue-violet petals, of which the lowest is lip-like and marked with the most delicate dark lines converging towards the centre of the flower. At the very heart of it there is a subtle yellowing and, behind, a spur offering a treasure of nectar: clearly the whole structure is an inducement for pollinating insects – a road map promising a reward. Through the beech litter brilliant green blades of a grass, wood melick, are pushing upwards to seek their share of precious light. Near the edge of the wood, lobed leaves of ground elder form a mat of freshest green; this notorious garden weed is constrained to behave itself in the wild.

But close observations of wayside flowers may be something of a distraction from a Chiltern spectacular. Perhaps I prefer to taste a few appetisers before becoming overwhelmed by the main course. For just beyond a short sward of wood melick is a shoreline edging the glory of the April beech woods in England: a sea of bluebells. The whole forest floor beyond is coloured by thousands upon thousands of flowers; a sea – because it seems unbroken and intense, like the yachted waters in a Dufy painting. But the display might equally be described as a carpet of bluebells; that word is more appropriate to the floor of a natural cathedral. Besides, the hue is a dark and rich blue, a shade not truly belonging to the ocean. Rather it is the cobalt blue of decorated tin-glazed wares produced at Delft, in Holland. In these woods, a magical slip is washed over the floor of the woodland as if by the hand of a master; a glaze that lasts only a few weeks, but transforms the ground beneath the beeches. From a distance there is a vague fuzziness about it, as if the blueness were evaporating upwards. The show is produced by massed English bluebells, Hyacinthoides non-scripta, a species unique to western Europe. This is old Britain’s very own, very particular and extraordinarily beautiful celebration of early spring. There is no physical sign in our wood of the Spanish bluebell interloper Hyacinthoides hispanica, the common species in English gardens. It is a coarser plant, with a more upright spike of flowers, and generally less elegant. In many places it is hybridising with the native species.

Each bluebell arises from a white bulb the size of a small tomato, and produces a rosette of spear-like leaves and a single flower spike; none is much taller than your forearm. It takes hundreds to make a splash of colour. The bells hang down in a line along the raceme in a single graceful curve. ‘Raceme’ is scientifically correct, of course, but how I wish that we could refer to it as a ‘chime’. Flowers at the base of the spike open first, their six delicate petals curving backward to form a skirt that curves away from the creamy anthers; it takes a while for the whole display to be over, as each flower up the spike comes to perfection one after another. With a natural variation in flowering times according to aspect and local climate, there are a few woodland nooks where bluebells open up precociously, and others where they linger longer. But wherever they bloom, theirs is a short-lived glory; and only when they are seen in numbers can the delicate perfume they produce be appreciated. As they generally reproduce from a slow multiplication of their bulbs, rather than from seed, the masses of English bluebells seen in our woods are a reliable indicator that they are of ancient origin. Hence it is likely that the flowers that delight my eyes today have been admired for centuries from the same spot near the edge of this very wood. The temptation is to pick a great bunch of blooms, but in a vase they lose vibrancy; they need a myriad companions to assert their natural magnificence. A thrush singing in mellow, repetitive phrases from deep within a holly bush adds some sort of blessing.

This is our own piece of classic English beech woodland, gifted with bluebells, covered with trees for generations, and changing at the slow pace of sap rising and falling. When Lambridge Wood was subdivided by the previous owner our little piece of it was arbitrarily christened Grim’s Dyke Wood, after the ancient monument that passes through the wood. The new name added an irresistible whiff of romance to the sales pitch that helped us to part with our money. It is a triangular plot with nearly equal sides, two of them marked out by public footpaths. We access the north-east corner of the triangle by vehicle along a track through Lambridge Wood that leads to a converted barn adjacent to our piece of woodland; the barn has a picturesque cottage next door that will also feature in this book. On the ground, it is hard to detect a very gentle slope of the whole plot to the south, but the incline is enough to admit a magical influx of winter light in the afternoon with the setting sun. About four acres (1.6 hectares) of woodland is not exactly a vast tract of forest, but it is enough to include more than 180 mature beech trees, which I counted, and bluebells galore, which I didn’t.

Lambridge Wood sits high in the Chiltern Hills, thirty-five miles to the west of London, near the southern tip of the county of Oxfordshire. Although so near the capital, the wood could be ten times further away from it and would not gain a jot more feeling of remoteness. As I contemplate the bluebells only the occasional growl overhead from aeroplanes bound for Heathrow reminds me that there is a great urban sprawl so close to hand.

The Chiltern Hills form the high ground for a length of more than fifty miles north-west of London. They follow the course of the outcrop of the pure white limestone known as the Chalk.3 The same rock makes the white cliffs of Dover, where England most closely approaches continental Europe; the sight of the cliffs has brought a lump into the throat of many a returning traveller, so it might be thought of as a peculiarly English rock, although it is actually widely spread around the world. As limestone goes, it is a very soft example of its kind – one that can be flaked with a penknife. Even so, it is harder and more homogeneous than the rocks that underlie it to the north, or overlie it in the direction of London, and differential weathering and erosion over hundreds of millennia has promoted the relative recession of the softer rocks to either side. The Chilterns stand proud.

The scarp slope along the northerly edge of the hills is surprisingly steep, and from the top of the Oxfordshire segment there are fine long views across the Vale of Aylesbury towards Oxford in the distance. That scarp lies only ten miles north-west of our wood. Half that distance away, Windmill Hill at Nettlebed is one of the highest points in southern England at 692 feet (211 metres) above sea level.4 The tops of the Chiltern Hills are richly wooded compared with the intensively farmed lowlands on the gentle plain to the north, where a patchwork of neat green fields or brown ploughed farmland is the rule. Google Earth or the Ordnance Survey map reveal much the same pattern, whether seen from above or in plan. The high ground has long fostered special pastoral practices, in which woods played a continuous and important part in the rhythm of country life. That is why they have survived. Our tiny patch is just one small piece of a larger tapestry stitched together from irregular swatches of trees, stretching over many miles. Other kinds of farmland are interspersed, to be sure, and in some places there has been sufficient clearance for open downland. But near our patch, copse, shaw, hanger and wood dominate the landscape.

When I first walked through Lambridge Wood as a newcomer to the Chiltern Hills I was overwhelmed by a feeling of entering a realm of eternal nature. Here was the antidote to jaded city life. The woods are unchanging; they help to put our small concerns into perspective. They are restorative, havens for animals and plants; safe places for the spirit. Such a perspective drenches Edward Thomas’s rapt accounts of woodland in The South Country, and has a modern mirror in Roger Deakin’s Wildwood nearly a century later. Here is the farmer A.G. Street writing in 1933 after listing more than one disappointment of middle age: ‘The majesty of the wood remains unaltered. As I wandered slowly through it, the terrific importance of my trouble seemed to fade away. The peace of the wood and the comfort of the still trees soon iron out the creases in my soul.’5 Surely some comparable emotion lay behind the enthusiasm with which we purchased Grim’s Dyke Wood, our own piece of peace. It was a romantic (or even Romantic) notion, and not wrong in its essentials. But, as Henry David Thoreau remarked of the English poets: ‘There is plenty of genial love of Nature but not so much of Nature herself.’6 The wood has indeed given much pleasure, but much of that delight proves to be an intimate examination of nature close to. And I now know that the history of nature is not only natural history. The wood is not eternal – it is a construct, a human product. It was made by our ancestors, modified repeatedly, nearly obliterated, rescued by industry, forgotten and remembered by turn. The animals and plants rubbed along with history as best they could, mostly unconsidered except as meat, fuel and forage: the natural history was part and parcel of the human history. The result is what we see today. Romantic empathy with ‘Nature’ is all very well, but it does have to brush up against the hard grit of history, which can soon polish off any coating of wishful thinking.

So this book is both romantic and forensic, if such a combination is possible. My diary records the status of the beech trees and the animals and plants, the play of the light, the passage of the seasons, expeditions and people, and the incomparable pleasures of discovery. I have also taken samples from the wood to the laboratory to dissect under a microscope. I have invited help from experts to identify tiny animals – mostly insects – about which I know little. Add to this excursions into historical literature and archives, and much time spent scrutinising scratchy ancient maps, deeds and sales catalogues to understand how the wood fared under management for profit or pleasure, and its place in the economy of estate, county and country. I have interviewed those who have known the woods during long lives. There will be a little geology, and more than a touch of archaeology.

Several of my previous books have dealt with big themes: the history of life or the geology of the world refracted through a personal lens. This book is the other way round: a tiny morsel of a historic land looked at all ways. The sum of all my observations will lead to an understanding of biodiversity – the variety of animals, plants and fungi that share this small wood. Biodiversity does not just belong to tropical rainforests or coral reefs. Almost every habitat has its own rich assemblage of organisms competing, collaborating and connected. What is found today is the result of climate, habitat, pollution or lack of it, history and husbandry. For me, the poetry of the wood derives from close examination as much as from synthesis and sensibility. But I am aware that description alone does not necessarily lead to understanding. This example from what may be Wordsworth’s worst poem (‘The Thorn’) comes to mind: