Полная версия

The Wood for the Trees: The Long View of Nature from a Small Wood

In 1828 J.S. Mill undertook his own bipedal tour that passed through our part of Oxfordshire.6 Open fields yielded abundant white-flowered wild candytuft, ‘one of the commonest of all weeds’ (Iberis amara), which is now a rare plant – I eventually ran it down myself on clear ground on Swyncombe Down, nine miles from our wood. His record of thorow wax (Bupleurum rotundifolium) might be one of the last for the county: this species is close to extinction in Great Britain, and Mill noted its rarity even then. On 5 July he approached Henley from Nettlebed: our patch. You may imagine the pleasure his subsequent writing gave me.

The woods are the great beauty of this country. They are real woods, not copse, that is, they are not cut down for fire-wood, but allowed to grow into timber, though not to any great age, nor are there, as far as we could perceive, many very large or fine trees among them … We stopped at the White Hart, Nettlebed for the night, and in the evening walked down the hill by the Oxford Road towards Henley. It passes through a fine forest-like beech wood, and on the whole the ascent to Nettlebed from Henley is far more beautiful than any thing else which we have seen in its vicinity.

I cannot prove that John Stuart Mill walked exactly along the footpath past our wood, although it is hard to see how a woodland ascent towards Nettlebed from Henley could have taken any other route. His praise for its beauty is not the least of it. The woods he described are very like those that still flourish today in this corner of the Chiltern Hills; the same stately ‘forest’ of mature timber trees, but yet lacking any truly ancient giants such as survive in old parkland or as parish boundary markers. My wife and I discovered a massive ancient beech pollard along a path in Nettlebed that must have been four hundred years old at least, all gnarled and knobbly and hollowed out. There are a few in the area. But no, Lambridge Wood was a working wood two hundred years ago, a beechen grove permitted to grow on to timber, but not to senility. We shall see, however, that nothing is forever, and our wood would have had different employment in earlier and later times.

Nor can I prove that John Stuart Mill walked through the wood in the company of George Grote, but I like to think that circumstances favoured it. They were friends already in the early 1820s. Mill was both an admirer and a reviewer of Grote’s writing, and particularly his monumental history of Greece (1846–56) in twelve volumes:7 a work not perhaps as beloved as Gibbon on Rome, but with a similarly vast reach and ambition. The two prolific writers shared what might broadly be called liberal and reformist views, and were Utilitarians. The seat of the banking Grote family was Badgemore House, which has been mentioned as the estate adjoining Greys Court directly to the east. Part of the Henley end of Lambridge Wood was within that estate; tracks ran onwards into our part of the greater wood. George’s father was fond of country pursuits, and went hacking on horseback through our woods and onwards to Bix. Young George (then still a banker) and his wife would make the forty-mile journey from London to spend ten days with his parents, and on one occasion Mrs Grote drove all the way in her own one-horse vehicle while her husband rode for four hours separately on horseback.8 Although George Grote was much attached to Badgemore, in the days before the railway it was hardly a practical commute. By 1831 it was clear that the country house should be given up, and George left for the metropolis to devote more time to reformist politics. We shall see that all the manor houses surrounding our wood had political connections with the capital at one time or another.

As for contemporary writers, Richard Mabey’s memoir of Chiltern countryside9 is centred on a region not very far from Lambridge Wood, while Ian McEwan described a long walk through our chalk country in his 2007 novel On Chesil Beach. This area of southern England proves to be almost as crawling with writers as with other invertebrates.

Hard grounds

The ground in this part of the wood is crunchy under my boots. Beneath a few of last year’s fallen leaves and under the questing loops of bramble shoots there appears to be nothing but rock. I am attempting to dig a hole to explore the surface geology, but my spade refuses to make any progress. Its blade twists and complains against a barrier of stones. I will have to employ my geological hammer to solve the problem.

The pick side of the hammer starts levering up lumpy flints, some bigger than my fist. They leave the damp ground reluctantly, with a sucking noise. Where I hammer downwards into the growing hole, sparks fly where steel meets flint. Briefly, there is a smell of cordite; in the days of flintlock pistols that smell would have been a familiar one. Flints were used to strike the spark that ignited gunpowder before a shot could be made. Our flints are embedded in reddish ochre clay that tries to hold on to them, clay that can easily be rolled into a coherent ball between the palms of my hands, and sticks to the fingers. The exterior of most of the flints is white when wiped clear of its clay coat, but where the hammer has shattered one of the larger flints its interior is strikingly black, and mottled in patches. It is a hard rock, but a brittle one shot through with flaws. Much of the wood is effectively floored with flint. Of the chalk of the Chilterns there is no sign.

Just down the hill beyond the Fair Mile I know that chalk underlies everything. When the dual-carriageway road was repaired great masses of the white rock were dumped on the side, and I picked out a typical, conical fossil sponge called Ventriculites from the rock pile. Even within Lambridge Wood, further downslope towards Henley, a mysterious excavation known as the Fairies’ Hole (marked on even the oldest maps) is undoubtedly dug within the white limestone. The rock that makes the whole range of hills, ‘the rock that bore them up all on its back’, as H.J. Massingham said, is an understory of chalk. Within the chalk, hard flints form discrete layers, but they never dominate completely. This flint was ultimately derived from fossil sponges within the chalk that had internal skeletons made of silica struts. The silica was first dissolved, and then re-deposited in flinty layers as the original chalk ooze gradually hardened and transformed into the rock we see today. Whatever underlies Grim’s Dyke Wood on the higher ground evidently also lies on top of the chalk formation, but is largely made of flints derived from it, all stuck in a matrix of sticky clay. This deposit is called, unsurprisingly, clay-with-flints, and in the wood the flints are dominant.

Clay-with-flints caps the chalk in many parts of the Chiltern Hills.10 It is the product of many millennia of slow solution and weathering-away of the chalk; it is what is left behind when everything else is removed. Chalk is weakly soluble in rainwater, which is why water derived from an aquifer in the Chilterns leaves a limescale deposit behind in a kettle. After a very long time, as the chalk naturally disappears the originally scattered flints become concentrated. Flint is insoluble; in fact, this form of silica is well-nigh indestructible. It can be tossed into rivers or buried in gardens for centuries, and emerges unscathed. It will outlast the Chilterns.

To estimate the thickness of the clay-with-flint capping I walk slowly up from the end of the Fair Mile to Lambridge Wood along Pickpurse Lane (see comments on highwaymen), digging with my hammer into the bank until the telltale milkiness goes out of the soil. There are other signs to look for. Old man’s beard (Clematis vitalba), the nearest thing in the British flora to a liana, only grows on chalk – it will not tolerate clay-with-flints. Wild marjoram is no more forgiving. Plant roots sense chemistry with the exquisite palate of a connoisseur. Both the indicator plants grow in abundance near the bottom of the lane and fade away upward. By the time all evidence of chalk has disappeared I conclude that very roughly twenty feet of clay-with-flints must lie above. That is sufficient to make the thin soil on the high ground neutral or acidic compared with the alkaline soils on the slope and in the valley bottom. This saddens me, for many of the more glamorous plants love chalk: the whitebeam tree with big simple leaves with shining undersides; cheerful yellow St John’s wort; and many an orchid. I shall just have to live without them – I cannot argue with geology. Now I also know why our footpaths can become like quagmires after too much rain. That layer of impermeable clay does not drain well; it likes to make ponds. Some corner of our wood will always be damp.

Back to Grim’s Dyke Wood. I decide not to try to excavate much more of the recalcitrant stony ground. Instead I shall use the holes I have made to put down beetle traps, burying a few cups half-filled with lethal Dettol to ensnare night crawlers. As I tidy up, a different stone surprises me. Lying on top of the ground by a beech trunk is a pebble the size and shape of a goose egg. It is purple, and it is certainly no flint. Under my hand lens I recognise it immediately as hard sandstone. I soon see more examples of a similar cast, liver-coloured, always rounded off to make satisfactory hand specimens, by which I mean something that sits easily in the palm. They are all strangers. There is no rock formation I can think of in the Chiltern Hills, or in the Vale of Aylesbury beyond, or even further afield beyond Oxford, that might produce such pebbles. They have all their corners chipped off until they are satisfyingly elliptical in outline, and smoothly rounded at the corners. This is a form sculpted by long sojourn in a lively river; erosion has knocked them into shape little by little, polishing repeatedly over a very long time. How could they have got here, into the middle of our beech wood? There are other strangers too. A white pebble that might be a pigeon’s egg, judging from its shape and size; it’s another form of silica – resembling flint, but with a dense, swirling milky whiteness. Vein quartz, I will wager. It might have originated from a vein within granite or snaking along a fault fracturing other rocks. There is no source for such vein quartz anywhere around here. Strewn on top of the clay-with-flints are a bunch of lithological vagabonds from afar.

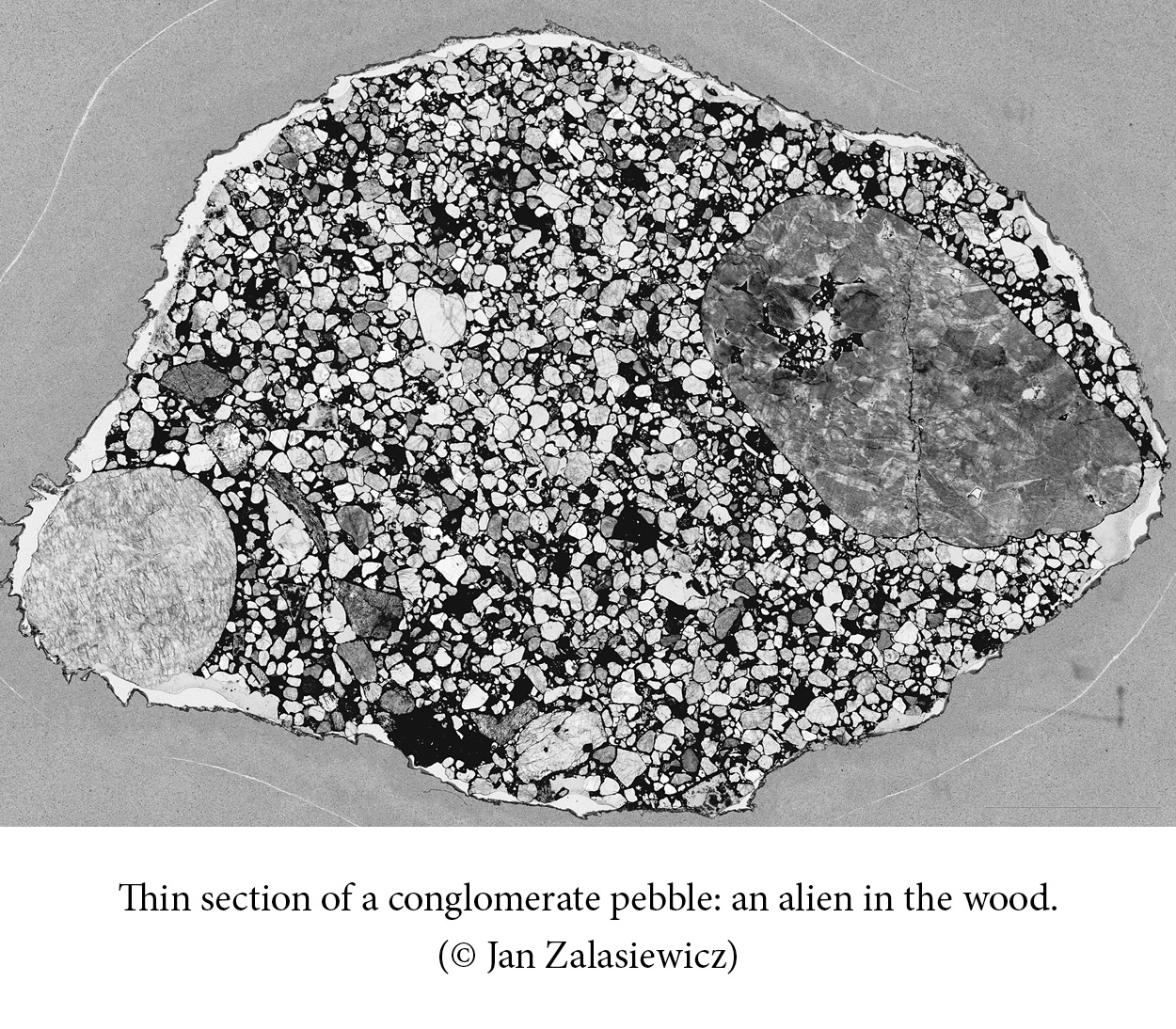

I decide to investigate further. At the Natural History Museum a skilful colleague cuts sections through my errant pebbles. Microscopic examination should show what they are made of, and reveal the secrets of their derivation. The samples are sliced using a diamond saw; then a thin sliver is mounted on a glass slide and reduced in thickness so much that light can penetrate the minerals that make up the rock; they can now be examined under a petrological microscope. I learned my microscopy skills as an undergraduate in a dusty laboratory in Cambridge, and distant memories stir as I stare down the eyepiece.

The vein quartz pebble proves to be typical. Under the microscope it shows as an irregular patchwork of grey or slightly yellowish crystals, with trails of tiny bubbles. It could have originated from several geological sites. However, one sample has several good pieces of similar-looking rounded vein quartz embedded within a chunk of the sandstone, like plums in a pudding. Maybe the quartz pebbles were derived from the same sandstone formation, only a part of it that was much coarser – a conglomerate, in geological terms. The pebbles must have been incorporated into the sandstone from some still older source. The sandstone itself is curious and distinctive. The individual sand grains are clear enough as masses of rounded outlines under the microscope, and they are of similar size to those that might be found on a beach today. But they are glued together by dark-red cement, without doubt full of iron. This is the mineral that gives the pebbles their rich red colour. The sandstone is recognisable, and it can be run down to its source. The pebbles must be Triassic in age (about 235 million years old), and they come from the English Midlands.11 The old name for them was from the German – Bunter sandstone12 – and they date back to a time when Britain was hot and arid and the geography of Europe had an utterly different cast. As for the indestructible milky quartz pebbles, some of them originated from the erosion of still older rocks long before they in their turn became incorporated into the Bunter sandstone; they might be as old as a billion years. Enmeshed under our own beech roots we have pebbles that account for a quarter of the history of the earth; and they arrived in the Chilterns by water, without question.

The vigorous river that brought down the pebbles from eighty miles to the north-west was an ancestor of the same River Thames that now flows sedately two miles to the east of the wood.13 During the Pleistocene Ice Age (2,588,000 to 11,700 years ago) thick continental glaciers to the north waxed and waned by turn, diverting all Europe’s great rivers at some times, providing the source for vast spreads of gravel at others. The ancient Thames left behind a record of this complex history in its former river terraces, the remains of which are scattered around the Chilterns and the London Basin. The oldest of these terraces is close to our wood, at Nettlebed. The exotic pebbles that I found in the wood are well known from a younger terrace, a set of strata called the Stoke Row Gravels.

The village that gives that formation its name is about four miles west of the wood, high on the Chiltern plateau. It is home to a most implausible structure, a little piece of India by a village green such as Cecil Roberts would have described as being quintessentially English. The Maharajah’s Well was dug by hand 368 feet down into the chalk, passing on the way down through the overlying gravels relevant to our wood, and all at the personal expense of the Maharajah of Benares, who also supplied the exotic, elegant and ornate canopy. His gift was reciprocation for a well dug in India at Azimghur by Edward Reade (‘squire’ of Stoke Row) in 1831. The Maharajah remembered that Reade had told him how his little home village on the top of the Chiltern Hills was most precariously supplied with water. His remarkable gift of the Maharajah’s Well was officially opened in 1864, and did its job efficiently for seven decades.

Professor Phil Gibbard tells me that the Midland ‘connection’ was open for well over a million years, until about 450,000 years ago. Although the huge Pleistocene ice sheets never reached as far south as the wood, their influence could not have been more profound. An icy climate sculpted the Chiltern landscape. It scrubbed the landscape to a tabula rasa on which all its subsequent history was inscribed; this marks the baseline of my natural history. I have to imagine a landscape stripped of trees. The slopes of the hills are bare, with only the hardiest herbs able to cope with the frigidity to the south of the permanent ice. Now indeed Cecil Roberts’s description of the valley up to Stonor as a ‘ravine’ may be nearer the mark, for the Chiltern country is riven with steep-sided valleys. Cold summer streams that flow with rejuvenated force following the annual melt carve vigorously down into the soft chalk, which is still too deeply frozen to allow the tumbling waters simply to be absorbed. The streambed is choked up with flint pebbles. In Arctic latitudes I have watched just the same fitful progress of jostling stones during the brief summer – their percussion kept me awake. The legacy of the frozen era still marks the ground: not only the implausible sheerness of some Chiltern hillsides, but also valley bottoms floored even now by ancient stream gravels.

Old names were bestowed by the Ice Age, like Rocky Lane, which runs up a valley on the south-western side of the Greys estate. Then, somewhat over eleven thousand years ago, the climate warmed for good, and now I must populate the hills with trees. Pioneers at first, small willows, hardy conifers; then birch, pine and aspen; and next, and not necessarily in this order, the broadleaved trees that came to make the original wildwood: oak, ash, lime, elm, hazel and beech. Oliver Rackham14 tells us that the lime species he calls pry (Tilia cordata) – the small-leaved lime – was dominant in many of those early woodlands. It still lurks, mostly unremarked, in a few places in the Chiltern Hills, but not in our wood. About six thousand years ago ‘Stone Age’ humans were already beginning to fell the virginal forests, where previously arboreal old age and accident had been the only foresters. The streams that had once carved the ‘ravines’ were now absorbed into the defrosted chalk, leaving a legacy of steep dry valleys, like the one that runs from the Fair Mile to Stonor Park; though it is not quite dry, for after unusually wet winters the water table rises until streams such as the Assendon Brook reappear, bounding alongside the tiny roads and causing cyclists to swerve and walkers to chide their wet Labradors.

I hold a couple of the liver-coloured sandstone pebbles and a quartz keepsake up to the May sunshine. So much can be read from these fragments. I think of the lines from As You Like It:

And this our life, exempt from public haunt,

Finds tongues in trees, books in the running brooks,

Sermons in stones, and good in everything.

These remarkable, sermonising samples of rocks that might have passed unnoticed are next to be added to the collection.

Maiden ladies and geraniums

In 1787 Mary, Dowager Lady Stapleton, moved into Greys Court as her dower house, and women dominated that establishment for the next eighty years. After she died at the age of ninety-one in 1835, Mary’s daughters Maria and Catherine stayed on in the big house that owned Lambridge Wood until the younger sister Catherine’s death twenty-eight years later; both sisters also lived to a great age. The intellectual ferment in London that preoccupied their neighbour, George Grote – and the circle that included John Stuart Mill – passed them by. Rather, the Church engaged them fully, and led them to charities directed at the moral and religious education of the less fortunate in the parish of Rotherfield Greys. The rents from tenancies guaranteed their gentility, if not their spinsterhood. It must have been a quiet time at the ancient house.

Mary’s son James was at Greys Court in the earlier days, and his friend from Christ Church, Oxford, Charles Kirkpatrick Sharpe, stayed with him often, and wrote frank letters to his mother at Hoddam Castle peppered with observations that exactly match his surname.15 On 12 January 1801 he was describing his Christmas at Greys, ‘which began, woe’s me! like most other gambols, with laughter, and ended in tears’. He described the entertainments the local town had to offer thus:

Miss Stapleton, her brother, and myself, repaired in high feather to a ball at Henley, the night after Christmas, and were much amused in many ways. The company consisted of the town gentry, and the progeny of farmers in the neighbourhood; the clowns with lank, rat-tail hair, and white gloves drawn tight on hands which they knew not how to dispose of; the clownesses with long stiff feathers stuck round their heads like those of a shuttle cock, and wealth of paste beads and pinchbeck chains. They came all stealing into the room as if they were doing some villainy, and joyful was the meeting of the benches and their bums. But the dancing did them most ease; the nymphs imitating the kicking of their cows, the swains the prancing of their cart horses. But joy of joys! Tea was brought at twelve, and off came all the silken mittens and pure white gloves in an instant, exposing lovely raw beef arms and mutton fists more inured to twirl mopsticks and grasp pitchforks than to flutter fans or flourish bamboos.

There is a precision of observation here that almost mitigates the snobbery. Walter Scott wrote of Sharpe: ‘he has great wit, and a great turn for antiquarian lore’. Nor did the poor Misses Stapleton escape his gimlet eye. A year later he wrote:

I made out my visit to [James] Stapleton, and yawned with him for a week. They are such good dull people at Greys Court! The sober primitive women do nothing the whole day but fiddle-faddle with their greenhouse, like so many Eves, and truly they are in little danger of a tempter, for their faces would frighten the devil, not to mention men.

The only portrait I know depicting the sisters (and brother), by Thomas Beach in 1789, suggests this judgement might be unfair. The large painting hangs on the staircase in the grand Holburne Museum in Bath. The two girls are dressed rather fetchingly as shepherdesses. Their features are pleasantly strong, although there is a certain wistfulness in their expressions. Perhaps they had already foreseen their long and genteel confinement to Greys Court. We get a brief sketch of their later lives from the recollections of an old-timer published in the Henley Standard on 29 July 1922. When he was young a familiar sight was ‘the old Post Chaise, with the red jacketed and booted postilion, which brought the old Misses Stapleton of Greys Court almost daily into Henley’. They evidently kept up appearances.

The preoccupation of the Stapleton sisters with greenhouse horticulture was, I dare say correctly, observed by Mr Sharpe. Miss Stapleton won the first prize at the Henley Horticultural Show in 1837 for ‘a boquet of greenhouse flowers’.16 There are still wooden-framed greenhouses dating back to Stapleton times within the brick-and-flint-walled vegetable garden at Greys Court. Catherine Stapleton was particularly expert on pelargoniums. Her knowledge was recognised by the honour of having a cultivar named after her in 1826: ‘Miss Stapleton’. It is still available as a variety from specialist nurseries. It has charming rich red flowers, paler at the base and decked with a single dark spot on each petal.17 I have a pot of it on my window ledge. With her botanical predilections I am certain that Catherine walked in her own woodland. There she would certainly have found the only member of her favourite geranium family that grows in Lambridge Wood (Grim’s Dyke Wood included) – the common wayside weed Geranium robertianum, ‘herb Robert’. She, like me, must have bent down to examine its small, richly red flowers, and must have smelled its curious pungency, and felt the glandular stickiness of its divided leaves, so often tinted blood-red, and noted its odd, stilt-like roots. She too would have known that this herb was named for Nicolas Robert, a pioneer of accurate botanical illustration in seventeenth-century France. I can imagine sharing with her a moment’s communion over a mutual enthusiasm before the proprieties of the time sent her scurrying back to the old house.

Fiddleheads

Ferns have subtle beginnings. As the bluebell leaves fade to little more than slime, ferns push out their new fronds. In the larger clearing, fresh shoots of brambles seem to unfold their leaves even as I watch. Every early shoot – Dylan Thomas’s ‘green fuse’ if ever I have seen one – is almost soft, and downy, and I have nibbled one and found it pleasant and nutty. Today, the backwardly curved spines lining the veins on the underside of the newly unfurled leaves are already beginning to harden – soon they will be capable of delivering a scratch. The bramble patch is impenetrable and intimidating, and the new growth will serve only to thicken its dense conspiracy. Amidst the scrubbiest part of it are dry, brown, fallen fronds of last year’s male ferns (Dryopteris filix-mas). From their centre new growth rises assertively. Rebirth started obscurely a month ago as a cluster of dark knobs. Each one soon rears up of its own accord into a fiddlehead, a kind of self-unwinding spiral that uncurls upwards into the spring sunlight. It is rather like that irritating party toy with which children love to blow raspberries at their friends. At the fiddlehead stage it is said to be edible, and I can see a bruised crown where deer have treated the new growth as a seasonal snack. Even now some of the fronds are opening out, like some unfathomable piece of origami, unsheathing the elegant, pinnate blade that will see the year out. The clustered male fern fronds triumph over the brambles. Once the fronds are fully dark green they will be primed with the poisons that have helped them survive since before the dinosaurs; and then their spore packages will ripen in tiny curved organs beneath each leaflet.