Полная версия

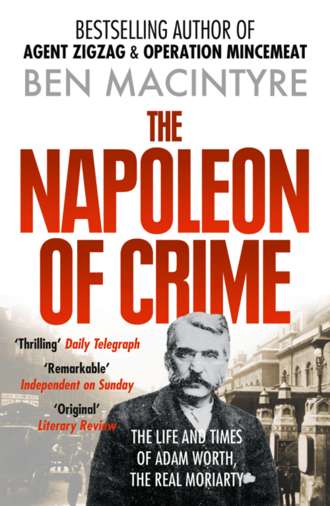

The Napoleon of Crime: The Life and Times of Adam Worth, the Real Moriarty

‘The robbery startled all Paris, and was the means of attracting suspicion to the house [which] lost prestige and soon went to pieces.’ By now Pinkerton had begun recruiting international support in his bid to close the American Bar, most notably Inspector John Shore of Scotland Yard in London. Shore had been receiving reports for some time of a clutch of criminals operating out of Paris and he, too, began to demand that the Paris police shut down the establishment once and for all. Through his spies, Worth learned that the English policeman was putting pressure on the French authorities and his alarm redoubled. It was the first time Shore and Worth had crossed swords.

‘The place was finally raided by the police,’ Pinkerton reported, but this time the Sûreté were not going to be beaten by Worth’s alarm system. ‘The bar-tender was seized as soon as they entered, and rushing upstairs, they found the gambling in full blast.’ Worth and Kitty, by lucky chance, were not in the building at the time, but ‘Wells [Bullard] and others [a pair of unfortunate croupiers] were arrested and charged with maintaining a gambling house, but were admitted to bail.’ Bullard, the nominal owner of the bar, skipped bail and fled to London, leaving Worth and Kitty to sort out what remained of the business.

Worth later told Pinkerton that he had already decided the bar would ‘never again be a success the way he wanted it’, and the club was sold to an ‘English betting man or bookmaker named Jack Ballentine’ who kept it going for two more years before the American Bar was finally closed.

Pinkerton later wrote, on Worth’s authority, that ‘the ruction which I kicked up was the means of ruining Bullard in Paris, driving him out, breaking up the bar and sending, as he termed it, all of them on the bum.’ But rather than resenting Pinkerton’s rude intrusion into his affairs, Worth seems to have admired Pinkerton’s detective efforts. ‘Afterwards when we met in London [he said] that he had always fancied me and found that I was a man who kept his own counsel and that he had always felt a kindly feeling towards me,’ Pinkerton wrote. They might be on opposite sides of the law, but the thief and the detective had already developed a healthy respect for one another’s talents, which would eventually blossom into a most unlikely friendship.

So far from being ‘on the bum’, Worth was still a substantially wealthy man. The breaking up of the American Bar simply closed one chapter in his life and opened another. He increasingly craved, for himself and the aspiring Kitty, if not genuine respectability, then at least its outward trappings and, at the age of just thirty-one, he could afford them.

There was really only one destination for a man of social and criminal ambition, and that was London, centre of the civilized world, where the gentlemanly ideal had been elevated to the status of a religion, abounding with wealth and, therefore, felonious opportunity.

Victorian Britain was reaching the pinnacle of its Greatness, and smugness. ‘The history of Britain is emphatically the history of progress,’ declared the intensely popular writer T.B. Macaulay. ‘The greatest and most highly civilised people that ever the world saw, have spread their dominion over every quarter of the globe.’ A similar note of patriotic omnipotence was struck earlier by the historian Thomas Carlyle: ‘We remove mountains, and make seas our smooth highway, nothing can resist us. We war with rude nature, and by our restless engines, come off always victorious, and loaded with spoils.’ For a crook at war with the natural order, such heady recommendations were irresistible. Huge spoils, and the social elevation they brought with them, were precisely what Worth had in mind.

Piano Charley was already across the Channel, operating under the cover of a wine salesman and steadily drinking a large proportion of his supposed wares. Worth, Kitty and the rest of the gang packed up what was left from the American Bar – the chandeliers, brass fittings and oil paintings – and merrily headed back across the Channel to the great English metropolis.

The upper floors of what was once Worth’s gambling den are now the bedrooms of the Grand Hotel Intercontinental, one of the most expensive hotels in Paris. But still more appropriately, given the next phase of Worth’s life, the door to number 2 rue Scribe now leads into ‘Old England’, the chain of stores where one can still buy all the appurtenances, from monogrammed riding boots to top hats, of a pukka English gent.

SEVEN

The Duchess

BY COINCIDENCE, or fate, in 1875 Gainsborough’s portrait of Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, was also about to make a triumphant public reappearance in the English capital after long years in hiding. The subject of this painting had died some four decades before Worth was born, but she would play a defining role in his life.

Georgiana Spencer (pronounced George-ayna) was just seventeen in 1774 when she married William Cavendish, fifth Duke of Devonshire. The duke, one of the richest and oddest men in England, was also, by popular assent, one of the luckiest, for the eldest daughter of John, first Earl of Spencer, was already considered to be the most beautiful and accomplished woman in the nation. Poets praised her to the heavens, the Prince of Wales fawned on her, and painters vied with one another to reproduce her charms. Her detractors were equally emphatic, portraying her as an aristocratic slattern whose hats were too tall and whose morals were too low. Everyone had an opinion on Georgiana.

Thomas Gainsborough began his most celebrated painting of the duchess around the year 1787, and it was no easy commission, even for the greatest portraitist Britain has ever produced. There was something about the pucker of her lips, the hint of a smirk, playful and suggestive, that defied reproduction. Or perhaps it was simply the captivating presence of the sitter herself, ‘then in the bloom of youth’, that baffled the master. Gainsborough’s frustration mounted as he drew and redrew Georgiana’s mouth, trying to catch that fleeting, flirting expression, ‘but her dazzling beauty, and the sense which he entertained of the charm of her looks, and her conversation, took away that readiness of hand and happiness of touch which belonged to him in ordinary moments’. Finally he lost his temper. ‘Drawing his wet pencil across a mouth which all who saw it considered exquisitely lovely, he said, “Her Grace is too hard for me!”’

Gainsborough painted Georgiana, as far as we know, three times: as a child in 1763, a delightful painting ‘giving promise even then of her remarkable charms’ which now hangs in the collection of Earl Spencer of Althorp, England; and a second time in 1783, for a full-length portrait now in the National Gallery in Washington, D.C. In the latter painting the duchess is draped around a column in classically demure posture, but appears a trifle seedy and ‘greenish’ in Walpole’s words, possibly after a hard night on the town. By the time he came to paint her again both artist and sitter had become yet more celebrated and Gainsborough was plainly determined to capture Georgiana’s allure. Hence his frustration with the duchess’s elusive mouth.

He persevered, and the resulting portrait was a masterpiece, seeming to distil Georgiana’s delectable expression. Her left eyebrow is arched and winning, a tantalizing half-smile plays across her lips and beneath the huge cocked hat her glance is slyly mischievous. In one hand she grasps a blooming rose and in the other, pinched suggestively between thumb and forefinger, a ripe pink rosebud. Georgiana had not proved too hard for him after all, and the finished product was devastating, frankly sexual yet strangely coy.

She had been painted many times before and would be painted again by the greatest artists in the land, including Reynolds, Romney and Rowlandson. As one critic wrote in 1901, ‘More portraits exist of Georgiana than of any other English lady of the eighteenth century.’ Yet for grandeur and cheek, personality and piquancy, none matched Gainsborough’s painting of the duchess in full bloom.

There is no evidence that the portrait ever hung in the ducal home of the Devonshires at Chatsworth, but at around the time that Georgiana became pregnant by her lover, the future prime minister Charles Grey, the lovely Gainsborough painting abruptly and inexplicably vanished. Perhaps the duke, although himself a serial adulterer, found the portrait of his wife with her coquettish smile and arched brow too powerful a reminder of her affair, and banished it from his presence.

In the autumn of 1841, three years before Adam Worth came into the world, the London art dealer John Bentley was making one of his annual forays through England’s Home Counties in search of rare paintings. An astute art connoisseur, Bentley owned a thriving dealership in the metropolis and was much in demand as a valuer of old masters. Over the course of his career, for pleasure and profit, he had made it a rule to spend a few weeks every year wandering through the small villages and towns of England making enquiries as to whether any of the local residents had works of art or other antiques they wished to value or sell. Many a bargain was to be found in this way, and the practice enabled Bentley to shed, for a while, the cares and strains of metropolitan life in a bucolic and nomadic quest for art.

In this particular year, Bentley’s enjoyment of his annual outing had been sharply diminished by a stinking cold which had settled both on his chest, making him cough and sneeze, and on his mind, making him grumpy.

On the morning of 17 September, Bentley’s ill-humour and streaming nose were suddenly forgotten when his researches brought him to the small sitting room of one Anne Maginnis, an elderly English schoolmistress long retired. For there, above Mrs Maginnis’s fireplace, grimy but unmistakable, was the portrait of Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, by Thomas Gainsborough. Quite how the widow Maginnis, who had little money and even less interest in fine art, managed to get her hands on Gainsborough’s famous missing portrait has never been adequately explained. According to one account, the old lady ‘spoke of it as the portrait of a relative of hers, and that it was bought, not as the picture of the beautiful Duchess, but merely as “a Gainsborough”.’ Bentley never enquired too closely into how she had obtained the great picture, partly out of tact, but largely because he had immediately identified the missing duchess, knew a sucker when he saw one, and wanted to buy it, cheap.

No one can be sure quite what had happened to the painting in the intervening years. One biographer quotes the Reverend Henry Bate as referring to two Gainsborough portraits of the duchess, ‘one of which Lady Spencer has, the other, we think, is in Mr Boothby’s possession’. One possibility is Charles Boothby-Skrymshire, also known as ‘Prince’ Boothby, a man of fashion so nicknamed on account of his egregious social climbing and his tendency to ‘abandon friends as soon as he met people of higher social position or rank’. He was believed to be a close friend of the Devonshires, and may have obtained the picture when the duke decided he no longer wanted it. Prince Boothby committed suicide on 27 July 1800, whereupon his effects were ‘dispersed’. Another candidate for the elusive ‘Mr Boothby’ is Sir Brooke Boothby of Ashbourne Hall, just twenty miles from Chatsworth, a scholar, poet, friend of Rousseau and Charles James Fox, satirist and art collector who owned at least one other portrait of the duchess as well as a crayon drawing and was acquainted with his ducal neighbours. Sir Brooke may have sold the Gainsborough in 1792, when he suddenly ran out of money. Whichever Boothby had briefly owned the Duchess, the portrait had completely vanished until it cropped up again in Mrs Maginnis’s tiny cottage under Bentley’s knowing and excited gaze. The elderly woman plainly had no idea what the painting was, or what it was worth, for in a singular act of vandalism some years earlier she had cut off the Duchess’s legs just above the knee, shortening the painting to three-quarters of its original size and consigning Georgiana’s feet to the fire. Henry James would criticize the ‘very wooden legs’ in Gainsborough’s portraits, but that was hardly a reason for burning them, and Mrs Maginnis’s brainless surgery left the portrait out of balance: Georgiana seems almost overpowered by her vast hat. But even in these sadly reduced circumstances, Bentley recognized Gainsborough’s Duchess, admired her still-saucy smile, and scented a bargain.

Many years later Bentley’s grandson, one Sigismund Goelze, explained what had happened, recalling his grandfather’s discovery in a letter to The Times: ‘It was then hanging in her sitting-room, over the chimney piece, and, knowing that originally the picture was painted full-length, he asked her how it was that it only showed to the knees. The old lady told him that she had cut it down to fit the position it then occupied, and added that she had burnt the piece which she had cut off.’

Although Bentley could not be certain that this was indeed the Duchess, his expert’s hunch told him to take a gamble. The widow Maginnis, while no expert in matters artistic, knew the value of money and was, moreover, an experienced haggler. After some lively negotiations lasting several hours, the old lady agreed to let the art dealer take the painting away on the promise that he knew a man who might pay as much as seventy pounds for it. Bentley was careful not to mention whom the picture portrayed, for even thirty-five years after her death Georgiana’s remained the sort of household name that could only increase the expectations of an impoverished English schoolmistress.

On 6 October Mrs Maginnis wrote:

Sir, I am obliged by your prompt attention to the disposal of the picture, and will take £70 for it, ready money, if the gentleman will give it, as I feel assured you will make the most you can of it.

Hoping you are in better health than when I last saw you, I remain, Sir, your obedient servant, Anne Maginnis

In the end Bentley managed to persuade Mrs Maginnis to let him keep the portrait for the sum of fifty-six pounds, one of the most advantageous deals he ever made. According to his grandson, Bentley ‘never had the slightest doubt as to the genuineness of the picture; and to an artist it is obviously impossible for any copyist to successfully reproduce the swift, spontaneous touch of the greatest master of female portraiture’. The dealer carried the painting to London, where he cleaned it up and proudly displayed the Duchess to his admiring friends. ‘The picture remained in my grandfather’s possession for some time, and my mother still remembers it hanging in the dining room of her old home in Sloane Street,’ Goelze wrote.

Bentley subsequently agreed to sell the Duchess to his friend and fellow connoisseur, a silk merchant named Wynn Ellis –‘characteristically declining to take any profit, so I have been told’, Goelze reported. ‘Mr Bentley was the intimate friend and adviser of most of the great collectors during the early years of the late reign; but he made it a rule never to receive any remuneration for his services in assisting to form collections of pictures, a habit which I fear must in these days seem curiously Quixotic. The reason he gave was that in this way only could he prove his advice to be absolutely disinterested.’

Wynn Ellis (probably the painting’s fifth owner) started out in business, in 1812, as a ‘haberdasher, hosier and mercer’ and ended up as owner of the largest silk business in London and a man of immense wealth, excellent taste and profound views. As a Member of Parliament for Leicester and a Justice of the Peace in Hertfordshire, where in 1830 he purchased a large estate called Ponsborne Park, Ellis advocated the repeal of the Corn Laws and considered himself an advanced liberal. But his most trenchant views happened to address a pastime dear to Adam Worth’s heart, for Wynn Ellis ‘had an intense dislike of betting, horse-racing and gambling’. Ellis did not gamble on anything, and least of all on the great paintings which he purchased with his grand fortune. John Bentley, on the other hand, was a most canny art dealer who did not scruple to extract a tough bargain from an elderly schoolmistress. So whatever his grandson’s claims and the demands of friendship, it would have been far more characteristic of the man had Bentley charged Ellis a small fortune for the painting. Sadly, we will never know how much profit Bentley made on his investment of fifty-six pounds for the silk manufacturer – like other, later owners of the portrait – flatly declined to say what he had paid for it and allowed the rumour that he spent just sixty guineas on the purchase to circulate uncontradicted. Ellis sent the painting to be engraved by Robert Graves of Henry Graves & Co., and the result, simply identified as Gainsborough’s Duchess of Devonshire, was published on 24 February 1870.

Ellis owned one of the finest art collections in England, and the great Gainsborough now took a prominent place in it. Did Wynn Ellis know for sure that ‘the painting which had been mutilated to hang above a foolish old woman’s smoke-grimed mantel shelf was … a pearl of rarest price? Some, subsequently, had their doubts. ‘There was … a very general belief among those interested in art matters, that not a few of the pictures [in the Wynn Ellis collection] bearing the names of distinguished English painters were copies or imitations.’ Had Wynn Ellis been too hasty in declaring the painting to be Gainsborough’s Duchess of Devonshire? ‘Though a great lover of art he was not an infallible judge,’ one critic observed, ‘and it is recorded that his discovery that three imitation Turners had been foisted upon him at great prices led directly to his death’ – an event which took place on 8 January 1875, when Ellis was eighty-six years old and had amassed a fortune, it was estimated, little short of six hundred thousand pounds. His 402 paintings, along with ‘watercolour drawings, porcelain, decorative furniture, marbles &c.’ were left to the nation. The trustees of the National Gallery selected some forty-four old masters, as directed under the terms of Ellis’s will, and the rest of the vast collection was put up for auction. Gainsborough was then considered to be a modern artist and so that painting, too, was offered for sale by the auction house of Messrs Christie, Manson & Woods. After years in mysterious obscurity, Gainsborough’s Duchess was about to make her first public appearance for nearly a century, and tales of the charming Georgiana and her piquant history began to circulate once more in London’s salons. The auction was set for 6 May 1876, and suddenly the Duchess was all the rage again: where the Georgians had fallen in love with the rumbustious woman herself, the Victorians were about to be smitten by Georgiana’s portrait.

EIGHT

Dr Jekyll and Mr Worth

TO MARK THE FIRST STAGE of his transformation from the raffish boulevardier of the rue Scribe to the worthy gentleman of London, Adam Worth established himself, Kitty and Bullard in new and commodious headquarters south of the Thames, using the remaining profits from the sale of the American Bar and the stolen diamonds. Alerted by the Pinkertons and the Sûreté, Scotland Yard was already on guard and soon sent word to Robert Pinkerton, brother of William and head of the Pinkerton office in New York, that the resourceful Worth ‘now delights in the more aristocratic name of Henry Raymond [and] occupies a commodious mansion standing well back on its own grounds out of the view of the too curious at the west corner of Clapham Common and known as the West Lodge.’ Bow-fronted and imposing, the West, or Western Lodge was built around 1800 and had previously been home to such notables as Richard Thornton, a millionaire who made his fortune by speculating in tallow on the Baltic Exchange, and more recently, in 1843, to Sir Charles Trevelyan: precisely the sort of social connections Worth was beginning to covet. The rest of the gang, including Becker, Elliott and Sesicovitch, lived in another large building leased by Joe and Lydia Chapman at 103 Neville Road, which Worth helped to furnish with thick red carpets and chandeliers.

Worth almost certainly knew that Scotland Yard was watching him but, since he entertained a low opinion of the British police in general and Inspector John Shore in particular, the knowledge seems to have worried him not one jot. With a high-mindedness that was becoming characteristic, Worth made no secret of his opinion that Shore was a drunken, womanizing idiot – ‘a big lunk head and laughing stock for everybody in England … he knew nobody but a lot of three-card monte men and cheap pickpockets’. Worth had come a long way in his own estimation since he too had been a lowly pickpocket on the streets of New York.

But while Worth was beginning to take on airs, styling himself as an elegant man about town, and while he set about laying the foundations for a variety of criminal activities, the original threesome was beginning to fall apart. Back in October 1870, Kitty had given birth to a daughter, Lucy Adeline, who would be followed, seven years later, by another, named Katherine Louise after her mother. The precise paternity of Kitty’s daughters has remained rather cloudy, for obvious reasons. Kitty herself may not have known for sure whether Bullard or Worth was the real father of her girls – conceivably they may have shared them, one each, as they did with everything else – but most of their criminal associates simply assumed that the children were Worth’s, as he seems to have done himself. William Pinkerton believed that Worth had simply taken over his partner’s conjugal rights when Bullard became too alcoholic to oblige. ‘Bullard, alias Wells, became very dissipated; his wife, in the meantime, had given birth to two children, daughters, who were in reality the children of Adam Worth,’ the detective stated.

More irascible and introverted with every drink, Bullard was no longer the carefree, dashing figure Kitty had fallen for at the Washington Hotel in Liverpool. He would vanish for long periods in London’s seamier quarters and then return, crippled with guilt and hangover, and play morosely on the piano for hours. To make matters worse, Kitty had learned of Bullard’s pre-existing marriage and his children by another woman. Though she had few qualms about sharing her favours with two men, Kitty was furious when she discovered Bullard was not only a depressing drunk but also a bigamist.

Aware of Kitty’s restlessness and hoping to keep her by dint of greater riches, Worth was now laying the groundwork for the most grandiose phase of his criminal career. In addition to the Clapham mansion, with its tennis courts, shooting gallery and bowling green, he also took apartments in the still more fashionable district of Mayfair, renting a large, well-appointed flat at 198 Piccadilly ‘for which he paid £600 a year’. The apartment was just a few hundred yards up the street from Devonshire House at number 74, where the duchess once entertained on such a lavish scale, and is now the Bradford & Bingley Building Society – precisely the sort of business Worth would once have had no hesitation in robbing. From here, with infinite care, Worth began masterminding a series of thefts, forgeries and other crimes.

Using his most trusted associates, he would farm out criminal work, usually on a contract basis and through other intermediaries, to selected men (and women) in the London underworld. The crooks who carried out these commissions knew only that the orders were passed down from above, that the pickings were good, the planning impeccable and the targets – banks, railway cashiers, private homes of rich individuals, post offices, warehouses – selected by the hand of a master-organizer. What they never knew was the name of the man at the top, or even of those in the middle of Worth’s pyramid command structure. Thus, on the rare but unavoidable occasions when a robbery went awry, Worth was all but immune, particularly when the judicious filtering of hush money down through the ranks of the organization ensured additional discretion at every level. Ever the control fanatic, Worth established his own form of omertà by the force of his personality, rigid attention to detail, strict but always anonymous oversight of every operation, and the expenditure of a portion of the profits to ensure, if not loyalty, then at least silence. He was happy to entertain senior underworld figures knowing, like a mafia godfather, that their survival depended on discretion as much as his, but the lesser felons who were his main source of income never knowingly saw his face. Before long the Piccadilly pad became an ‘international clearing house of crime’.