Полная версия

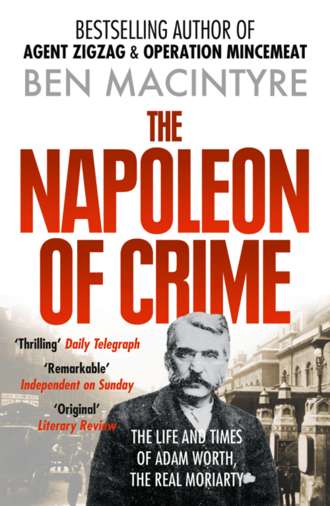

The Napoleon of Crime: The Life and Times of Adam Worth, the Real Moriarty

Two of Marm’s guests in particular would play crucial although very different roles in Worth’s future.

The first was Maximilian Schoenbein, ‘alias M. H. Baker, alias M. H. Zimmerman, alias “The Dutchman”, alias Mark Shinburn or Sheerly, alias Henry Edward Moebus,’ but most usually alias Max Shinburn, ‘a bank burglar of distinction who complained that he was at heart an aristocrat, and that he detested the crooks with whom he was compelled to associate’. For the next three decades the criminal paths taken by Adam Worth and Max Shinburn ran in tandem. The two law-breakers had much in common, and they came to loathe each other heartily.

Shinburn was born on 17 February 1842, in the town of Ittlingen, Württemberg, where he was apprenticed to a mechanic before emigrating to New York in 1861. Styling himself ‘the Baron’ from early in life, Shinburn later actually purchased the title of Baron Schindle or Shindell of Monaco with ‘the judicious expenditure of a part of his fortune’. Aloof, intelligent and insufferably arrogant, the Baron cut a wide swathe through New York low society. Even the police were impressed.

Inspector Thomas Byrnes of the New York Police Department considered him ‘probably the most expert bank burglar in the country’, while Belgian police offered this description of the soigne, multilingual felon: ‘Speaks English with a very slight German accent. Speaks German and French. Always well dressed. He has a distinguished appearance with polished manners. Speaks very courteously. Always stays at the best hotels.’ Shinburn’s looks were striking; he had ‘small blue penetrating eyes, long, straight nose, moustache and small imperial, both of brownish colour mixed with grey, moustache twisted at the ends, pointed chin … at times wears a full beard and sometimes a moustache and chin whisker, in order to hide from view the pronounced dimple in chin.’ His numerous encounters with the law and a youthful taste for duelling had left him with numerous other identifying features. After one arrest, a police officer noted these with grisly exactitude: ‘on back of left wrist … pistol shot wounds running parallel with each other and near the deformity in right leg … pistol or gunshot wound on left side … several small scars that look like the result of buck shot wounds; scar on left side of abdomen, appearing as though shot entered in the back and came through …’ Shinburn’s fraudulent aristocratic claims were full of holes, and so was the rest of him.

His criminal notoriety sprang principally from the invention of a machine which he maintained could reveal the combination of any safe: ‘a ratchet which, when placed under the combination dial of a safe, would puncture a sheet of calibrated paper when the dial stopped and started to move in the opposite direction. He would repeat this process until he had the entire combination.’ According to other police sources, ‘his ear was so acute and sensitive that by turning of the dial he could determine at what numbers the tumblers dropped into place.’

With his mechanical training, Shinburn also perfected a set of light and powerful safe-cracking tools which he was prepared to sell on to others for a price. ‘Shinburn revolutionized the burglar’s tools and put them on a scientific basis,’ recorded Sophie Lyons. The better to perfect his safe-busting technique, the Baron ‘for some time took employment under an assumed name in the works of the Lilly Safe Co. [whose] safes and vaults were considered among the best and most secure.’ But not for long. Leaving a trail of empty safes in his wake, Shinburn was eventually penalized by his own competence and the Lilly safe ‘came into such disrepute, that the company was forced into liquidation’.

‘The safe I can’t open hasn’t been built,’ Shinburn once boasted to Sophie Lyons.

By the time Worth encountered Shinburn in the mid 1860s, the latter had developed a name for himself as a man of importance among the bank-robbing fraternity by cleaning out the Savings Bank in Walpole, New Hampshire. Worth was ambivalent about the Baron. He admired his dandified dress and envied his reputation, but found his endless braggadocio and air of superiority unbearable.

Far more to Worth’s taste was another dark luminary of the underworld and Mandelbaum protege, Charles W. Bullard, a languid and alluring criminal playboy better known as ‘Piano’ Charley. The scion of a wealthy family from Milford which could trace its ancestry to a member of George Washington’s staff, Bullard ‘had a good common school education’, inherited a large fortune from his father while still in his teens and had gone to the bad, immediately and extravagantly. Having squandered his inheritance, Bullard briefly tried his hand in the butcher’s trade but gave up the occupation and ‘devoted his ability to the robbing of banks and safes’, for which he inherited a taste from his grandfather, who was said to be a burglar ‘in a small way’. Bullard’s ‘dissipation and a restless craving for morbid excitement made him a “fly” [skilled] crook’ and later an uncommonly daring and wily burglar. In New York low society he was considered ‘one of the boldest operators that has ever handled a jimmy or drilled a safe’.

‘Bullard is a man of good education,’ recorded one admiring police report, ‘speaks English, French and German fluently, and plays on the piano with the skill of a professional.’ Raffish, refined and handsome, with a wispy goatee and limpid eyes, Bullard had three passions in life, each of which he indulged to the limit: women, music and gambling. Through constant practice on his baby grand, Piano Charley had developed such ‘delicacy of touch’ that he could divine the combination of a safe simply by spinning the tumblers, while his piano sonatas could reduce the hardest criminal to tears and lure the most chaste woman into bed.

‘An inveterate gamester’, perennially short of funds, often outrageously drunk but always charming, Bullard was one of the most romantic figures in the New York underworld. Under the benign eye of Marm Mandelbaum, he and Worth struck up an immediate rapport.

Piano Charley Bullard’s crime-sheet included jewel theft, train robbery and jail-breaking. Early in 1869 he teamed up with Max Shinburn and another professional thief, Ike Marsh, to break into the safe of the Ocean National Bank in Greenwich Village after tunnelling through the basement. The venture was said to have realized more than a hundred thousand dollars, almost all of which ended up in Shinburn’s pockets. ‘The robbers were nearly a month at the work, and the bank was ruined by the loss,’ the police reported. Later that year, on 4 May, Bullard had again conspired with Marsh to rob the Hudson River Railroad Express as it trundled from Buffalo in upstate New York along the New York Central Railroad to Grand Central Station. Knowing that the Merchant’s Union Express Co. used the train to transport quantities of cash, with the connivance of a bribed train guard they ‘concealed themselves in the baggage car … in which the safe was stored and rifled it of $100,000’. Bullard and Marsh then leaped off the train in the Bronx with the cash and negotiable securities stuffed into carpet bags. The guard was found bound and apparently unconscious, with froth dripping down his chin – this turned out to be soap, and the guard was immediately arrested.

The Pinkertons, whose reputation had expanded to the point where they were called in on almost every significant robbery, had traced the thieves to Toronto and found Ike and Charley living in high style in one of the city’s most expensive hotels. After a long court battle, Bullard was extradited to the United States and gaoled in White Plains, New York, to await trial. Using what little money remained to them, the Bullard family hired an expensive lawyer to defend their wayward son. Like Worth, Piano Charley never passed up a criminal opportunity and arranged for one of his many women friends to extract a thousand dollars (the entire fee) from his attorney’s pocket ‘as he was returning to New York on the train’.

It was almost certainly Marm Mandelbaum who decided that Piano Charley, whose music-making was such a popular feature of her dinner parties, should not be allowed to languish behind bars.

Worth, already a close friend of the gaoled man, was selected for the job of getting him out, along with Shinburn. It was the first and only time the two men would work together.

One week after he was imprisoned, Bullard’s friends dug through the wall of the White Plains gaol and set both Ike and Charley at liberty, whereupon the crooks promptly returned to New York City for a long, and in Bullard’s case staggeringly bibulous, celebration. The Baron was immensely pleased with himself. ‘Shinburn used to take more pride in the way he broke into the jail at White Plains, New York, to free Charley Bullard and Ike Marsh, two friends of his, than he did in some of his boldest robberies,’ Sophie Lyons recounted. But the immediate effect of the successful gaol break was to cement the burgeoning friendship between Bullard and Worth. Piano Charley had the sort of effortless elan and cultural veneer that Worth so deeply admired and sought to emulate. On the other hand, Worth was clever and calculating, qualities which the suave but foolish Bullard singularly lacked.

They decided to go into partnership.

FIVE

The Robbers’ Bride

THE BOYLSTON NATIONAL BANK in Boston was a familiar sight from Worth’s youth. The rich burghers of Boston believed their money was as safe as man could make it behind the bank’s grand façade, an imposing brick edifice at the corner of Boylston and Washington streets in the heart of the city. According to Sophie Lyons, Worth ‘made a tour of inspection of all the Boston banks and decided that the famous Boylston Bank, the biggest in the city, would suit him’. Max Shinburn would later claim to have had a hand in planning the robbery, but there is no evidence his expertise was either required or requested. Indeed, Shinburn’s exclusion from this ‘job’ may have been the original source of the enmity between him and Worth. Ike Marsh, Bullard’s rather dim Irish sidekick in the train-robbery caper, was brought in on the heist, which was, like all the best plans, perfectly straightforward. Posing as William A. Judson and Co., dealers in health tonics, the partners rented the building adjacent to the bank and erected a partition across the window on which were displayed ‘some two hundred bottles, containing, according to the labels mucilage thereon, quantities of “Gray’s Oriental Tonic”.’ ‘The bottles served a double purpose,’ the Pinkertons reported; ‘that of showing his business and preventing the public looking into the place.’ Quite what was in Gray’s Oriental Tonic has never been revealed since not a single bottle was ever sold.

After carefully calculating the point where the shop wall adjoined the bank’s steel safe, the robbers began digging. For a week, working only at night, Worth, Bullard and Marsh piled the debris into the back of the shop, until finally the ‘lining of the vault lay exposed’.

‘To cut through this was a work of more labor,’ the Boston Post later reported. ‘So very quiet was the operation that the only sound perceptible to the occupants of adjoining rooms was like that made by a person in the act of putting down a carpet with an ordinary tack hammer. The tools applied were [drill] bits or augers of about an inch in diameter, by means of which a succession of holes were drilled, opening into each other, until a piece of plate some eighteen inches by twelve had been removed. Jimmies, hammers and chisels were used as occasion required for the purpose of consummating the nefarious job.’ In the early hours of Sunday, 21 November 1869, Worth wriggled through the hole, lit a candle inside the bank safe and surveyed the loot. ‘The treasure was contained in some twenty-five or thirty tin trunks’, which Worth now handed back out to his accomplices one by one. ‘The trunks were pried open, their contents examined, what was valuable pocketed and what was not rejected.’ As dawn broke over Boston, the three thieves packed the swag into trunks labelled ‘Gray’s Oriental Tonic’, hailed a carriage to the station and boarded the morning train to New York.

At nine o’clock on Monday morning, fully twenty-four hours later, bank officials opened the safe and were ‘fairly thunderstruck at the scene which met their gaze’. The entire collection of safe-deposit boxes, and with them the solid reputation of the Boylston National Bank of Boston, was gone.

THE BOSTON POST

TUESDAY MORNING, NOVEMBER 23, 1869

Yesterday morning Boston was startled. There is no discount on the word. A robbery of such magnitude as that of the Boylston National bank – amounting to from $150,000 to $200,000, in fact – which was perpetrated sometime between Saturday afternoon and Monday morning, is something quite out of the ordinary run in the municipal affairs of this city, and nearly if not quite too much for ready credence. But the robbery stands indisputably a robbery; and, taken as an exploit, considered in its aspect as a job, as one artist considers the work of another, it is one of the most adroit which it has ever been the fortune or misfortune of the press to record. The almost uniformly successful manner in which this class of burglary has been carried on throughout the country during the past few months may lead to the inference that the party or parties in the present case will escape the arm of the law, although it is true that the prime originator is as well known as any criminal need to be. The infinite cleverness with which his operations have been conducted from beginning to end, indicate him to be a man of no ordinary ability, and it seems very probable that, having so far succeeded in eluding police, he may escape altogether. Should he do so, he will find himself a richer man, even, than he had perhaps anticipated … The name by which the criminal is known is William A. Judson.

The Boston Post, barely able to suppress its admiration, was conservative in its estimate. The Pinkertons believed that ‘nearly one million dollars in money and securities’ had been stolen by Worth and his accomplices, a sum confirmed by Sophie Lyons. In the premises of William A. Judson and Co. police found ‘a dozen bushels or more of bricks and mortar’, about thirty disembowelled tin trunks and two hundred bottles of Gray’s Oriental Tonic. For a week the Boylston Bank robbery was Boston’s sole topic of conversation. ‘Everyone continues to talk about the robbery of Boylston Bank,’ the Boston Post reported gloomily a few days later. ‘But nobody – or nobody that has anything real to say – communicated anything new. On all sides it is admitted to be a very neat job, all the way from the Oriental Tonic clear through to the Bank safe.’

It was indeed Worth’s neatest job to date, yet the very success of the venture, the huge amount of money involved and the stated determination of the authorities to track down the thieves (spurred on by a reward of 20 per cent of the haul) left Worth and Bullard with an obvious dilemma. To stay in New York and attempt to ‘work back the securities’ in the traditional way was to invite trouble since even Marm Mandelbaum would think twice about fencing such hot property. They could take the cash, abandon the securities and head west, where the frontier states offered obscurity and where the law was, at best, partially administered. But Worth and Bullard, with their taste for expensive living and sophisticated company, were hardly the stuff of which cowboys are made, and the prospect of spending their ill-gotten gains in some dusty prairie town where they might be murdered for their money was less than appealing. A more attractive alternative was to make for Europe, where extradition was unlikely and wealthy Americans were welcomed with open arms, and few questions were asked. Big Ike Marsh had already decided to take early retirement with his share of the loot. He returned to Ireland via Baltimore and Queenstown, and was received in Tipperary with grand ceremony, a local boy made good or, rather, bad. In the end, the Pinkertons reported, ‘he gambled, drank and did everything he should not have done, and eventually returned to America for more funds.’ Poor Ike was arrested while trying to rob another bank in Wellesborough, sentenced to twenty years’ solitary confinement in Eastern Pennsylvania and ended his life ‘an old man, broken down in health, dependent on the charity of friends’.

Worth and Bullard rightly surmised that the Pinkertons would be called in after such a large robbery. Indeed, just a week after the bank heist, the detectives had traced the thieves and their spoil to New York and documents in the Pinkerton archives indicate that Bullard and Worth, thanks to some loose talk in criminal circles, were the prime suspects. The news that they were wanted men rapidly reached the fugitives themselves. ‘Those damned detectives will get on to us in a week,’ Bullard warned Worth. ‘I don’t want to be playing the Piano in Ludlow Street [gaol].’

Acting quickly, the pair dispatched the stolen securities to a New York lawyer, possibly either Howe or Hummel, with instructions to wait a few months and then sell back the bonds for a percentage of their face value and forward the proceeds in due course. At the time this was an accepted method for recovering stolen property, winked at by the police, who often helped to negotiate the return of securities themselves, to the advantage of both the owners and the thieves. ‘All [the robbers] need do is to make “terms” which means give up part of their booty, and then devote their leisure hours to plan new rascalities,’ noted the Boston Sunday Times, one of the few organs to raise objections to this morally dubious collusion. ‘There must be something radically wrong in the police system of the country when such transactions of [sic] these can repeatedly take place.’

Worth and Bullard then hurriedly packed the remaining cash into false-bottomed trunks, bid farewell to Marm Mandelbaum, Sophie Lyons and New York, and took the train to Philadelphia where the S.S. Indiana, bound for England, was waiting to take them, in style, to Europe and a new life. For this they would need new names, and in high spirits in their first-class cabin the pair discussed how they would reinvent themselves. Bullard elected to call himself Charles H. Wells and adopt a new persona as a wealthy Texan businessman. Worth’s choice of alias was inspired.

That year had seen the untimely and much-lamented demise, on 18 June, of Henry Jarvis Raymond, the founder-editor of the New York Times. Senator, congressman, political conscience and stalwart moral voice of the age, Raymond had succumbed to ‘an attack of apoplexy’ at the age of forty-nine and his passing was the occasion for some of the most solemn adulation ever printed. A single obituary of the great man described him as: patriotic, wise, moderate, honourable, candid, generous-hearted, hard-working, frugal, conscientious, masterly, modest, courageous, noble, consistent, principled, cultivated, distinguished, lucid, kind, just, forbearing, even-tempered, sincere, moral, lenient, vivacious, enterprising, temperate, self-possessed, clear-headed, sagacious, eloquent, staunch, sympathetic, kindly, generous, just, suave, amiable and upright. The New York Times ended this adjective-sodden paean to its founder by declaring that Raymond was ‘always the true gentleman … in fact, we never knew a man more completely guileless or whose life and character better illustrated the virtues of a true and ingenuous manhood.’ The newspaper’s journalistic rivals agreed: the Evening Mail noted, ‘He was always a gentleman … true to his own convictions.’ The Telegram called him ‘one of the brightest and most gentlemanly journalists the New World has ever produced’, while the Evening Post also noted ‘he was a gentleman in his manners and language.’ The grave in the exclusive Green-Wood Cemetery of this man of integrity, this ethical colossus, was marked with a forty-foot obelisk in honour of his achievements and virtue. ‘Contemporary opinion has rarely pronounced a more unanimous, more cordial or more emphatic judgment than in the case of the departed chief of the New York Times,’ that paper declared.

Worth, already hankering after the respectability to go with his new wealth, had read these breathless accolades (few could avoid them) and the repeated references to the late Mr Raymond’s ‘gentle-manliness’ had lodged in his mind. Appropriating the name of such a man would be a rich and satisfying irony, not least because Worth, an avid collector of underworld gossip, may have known that the great moral arbiter of the age had himself led a double life of which his readers and admirers possessed not an inkling. Officially, on the night of his death, the worthy editor had ‘sat with his family and some friends until 10 o’clock, when he left them to attend a political consultation; and his family saw no more of him until he was discovered, about 2.30 the next morning, lying in the hallway unconscious and apparently dying.’ The truth was rather more dubious, for in reality Henry Jarvis Raymond, man of virtue, had died of a sudden coronary while ‘paying a visit to a young actress’. Adam Worth now decided that, whether Henry J. Raymond resided in the heaven reserved for great men or in the purgatory of the adulterer, he did not need his name anymore. On the voyage to England he adopted this impressive alias (replacing Jarvis with Judson, in memory of the name he used for the Boston robbery) and kept it for the rest of his life. It was one of Worth’s wittiest and least recognized thefts.

Early the next year, two wealthy Americans swaggered into the Washington Hotel in Liverpool and announced they would be occupying the best rooms in the house indefinitely, since they planned an extended business trip. The pair were dressed in the height of fashion with frock coats, silk cravats and canes. Two Yankee swells fresh off the boat and keen for entertainment, Mr Henry J. Raymond, merchant banker, and Mr Charles H. Wells, Texan businessman, headed for the hotel bar to toast their arrival in the Old World. Mr Raymond drank to the future, Mr Wells, as usual, drank to excess.

Behind the bar of the Washington Hotel, as it happened, their future was already waiting in the highly desirable shape of Miss Katherine Louise Flynn, a seventeen-year-old Irish colleen with thick blonde hair, enticing dimples in all the right places and a gleam in her eye that might have been mistaken for availability but was probably rather closer to raw ambition. This remarkable woman had been born into Dublin poverty and had fled her humble origins at fifteen, determined even at that early age that hers would be a very different lot. Hot-tempered, vivacious and sharp as a tack, Kitty craved excitement and longed for travel, cultured company and beautiful things. Specifically, she understood the value of money, and wanted lots of it.

Mercenary is an unkind word. Kitty Flynn was simply practical. The squalor and deprivation of her early years had left her with a healthy respect for the advantages of wealth and a determination to do whatever was necessary, within reason, to obtain them. In her present situation this involved enduring, and blowing back, the good-natured and flirtatious chaff of the hotel’s regular drinkers. But when these same patrons overstepped the mark and were foolhardy enough to suggest that Kitty might like to consider some more intimate after-hours entertainment, they were left in no doubt, by way of a stream of vivid Irish invective, that the barmaid considered herself destined for rather greater delights than they could offer. The steamer from Dublin to Liverpool had been the first stage in Kitty’s planned journey to fortune and respectability; her current job as a hotel barmaid was but a way-station along the route. The arrival of Messrs Raymond and Wells opened up new and enticing vistas. Knights in shining armour were few and far between in Liverpool, and two wealthy Americans with money to burn were clearly the next best thing.