Полная версия

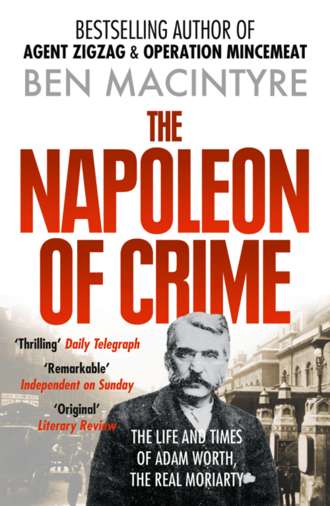

The Napoleon of Crime: The Life and Times of Adam Worth, the Real Moriarty

‘She was an unusually beautiful girl – a plump, dashing blonde of much the same type [as the actress] Lillian Russell was years ago,’ recounted Sophie Lyons. She was, like all the best barmaids, buxom. Her blonde hair curled into ringlets reaching to the middle of her back, which were arranged in such a way that they appeared to have exploded from the back of her head. Her features were delicate, her nose snubbed, her lips full, but it was her eyes, startlingly blue and slightly distended, that tended to reduce her admirers to putty. In certain lights she looked like nothing so much as an exceptionally attractive frog: which was only appropriate since Kitty would shortly embark on a career in which, as in the fairy tale, she would be kissed by a variety of princes, Charming and otherwise. In the best surviving portrait of her (a coloured version of a picture by the great French photographer Felix Nadar) Kitty Flynn is wearing an expression that hovers between flirtatious and simply wicked.

That expression had an electric effect on the newest arrivals to the Washington Hotel in January 1870. It was never clear which of the two felons first lost his heart to Kitty, but that both did so, and deeply, was accepted as fact by all their contemporaries. Sophie Lyons is characteristically blunt on the matter: ‘Bullard and Raymond [she uses Worth’s real name and his alias interchangeably] both fell madly in love with her.’

For the next month Kitty was besieged by these two very different suitors – the one small, dapper, almost teetotal and intense, the other tall, lugubrious and, as the Pinkertons put it, ‘inclined to live fast and dissipate’. Suddenly Kitty found herself being wined and dined on a scale that was lavish even beyond her own extravagant dreams and that stretched Liverpool’s resources to the limit. In spite of their amorous rivalry, the two crooks remained the closest of friends as they swept Kitty from one expensive candlelit dinner to another, as Bullard serenaded her and Worth did his best to persuade her that he, rather than his exotic partner, represented the more solid investment. ‘The race for her favour was a close one,’ records the inquisitive Lyons, ‘despite the fact that Bullard was an accomplished musician [and] spoke several languages fluently.’ Finally Kitty gave in to Piano Charley’s entreaties, and agreed to marry him. Yet for Worth she always reserved a place in her heart and, for that matter, her bed.

Kitty Flynn became Mrs Charles H. Wells one spring Sunday. The ceremony was performed at the Washington Hotel and a large and curious crowd of Liverpudlians turned out to watch the toast of the city being driven away in a coach and four by her handsome American husband. Adam Worth was the best man and, Lyons reports, ‘to his credit it should be said that the bridal couple had no sincerer well-wisher than he.’ Worth had good reason for his equanimity since, although Kitty had agreed to marry Bullard, she seems to have been only too happy to share her favours with both men. If Bullard objected to this arrangement he did not say so. Indeed, he was hardly in a strong moral position to do so, for, unbeknown to Kitty, he was married already. It was not until some time later that Kitty discovered Bullard had a wife and two children living in America. Conceivably Worth used this information to blackmail Bullard into sharing his wife. But that was hardly his style, and as the relationship between the two crooks remained entirely amicable, it seems more likely that the accommodating Kitty Flynn, the broad-minded Bullard, and Worth, who never let convention get in the way of his desires, simply found a ménage à trois to be the most convenient arrangement for all parties.

While Kitty and Charley enjoyed a short honeymoon, Worth passed his time profitably by robbing the largest pawnshop in Liverpool of some twenty-five thousand pounds’ worth of jewellery. The Pinkertons later gave a full account of the theft:

He looked around for something in his line, and found a large pawnshop in that city which he considered worth robbing … he saw that if he could get plaster impressions of the key to the place he could make a big haul. After working cautiously for several days he managed to get the pawnbroker off his guard long enough to enable him to get possession of the key and make a wax impression: the result was that two or three weeks later the pawnbroker came to his place one morning and found all of his valuable pieces of jewelry abstracted from his safe, the store and vaults locked, but the valuables gone. M

The robbery caused a minor sensation in Liverpool, where crime was rife but large-scale burglary rare. The Pinkerton account was written many years later, but seems to be largely accurate. Most of the bonds stolen from the Boylston Bank had now been ‘worked back’ to their owners and the bank had therefore decided to call off the costly detective agency, rightly concluding that the thieves were now beyond reach. But the Pinkertons continued to keep tabs, via a network of informers, on American criminals living abroad. In the coming years their information on Adam Worth and his activities as Henry Raymond grew increasingly detailed.

Robbing pawnbrokers was easy game, and Worth was becoming restless for more challenging sport in new pastures. Kitty was also eager to find more glamorous surroundings and Bullard did not care much where he went so long as there was money and champagne in plentiful supply, and a piano near at hand. Worth showered Kitty with expensive gifts (including his stolen gems), bought her expensive clothes and connived and encouraged her in her determination to leave her lowly origins behind. With his stolen money, Worth sought to shape and remake Kitty just as he was reinventing himself. But grimy Liverpool was no place for a would-be lady, and the great shared fraud required a brighter backdrop. At the end of 1870 the trio packed up their belongings, including the still considerable remnants of the Boylston Bank haul, checked out of the Washington Hotel and headed for Paris, where the war between France and Prussia, the siege of Paris and the impending lawlessness of the Commune had rendered the French capital a particularly enticing venue for a brace of socially ambitious crooks and their shared moll.

SIX

An American Bar in Paris

PARIS FURNISHED stark evidence of that peculiar brand of double standards Worth would absorb and adapt: under the Second Empire, a woman could be arrested for smoking in the Tuileries gardens but personal immorality was almost de rigueur. The surface was magnificent, but corruption and libertinism were rampant. Entrepreneurs speculated, hedonists indulged and English visitors railed about the ‘badness of the morals’. The great gay façade of the Second Empire had come tumbling down with the crushing of the French armies by the Prussian military machine, and more than twenty thousand people had died in the horrific violence of the Commune that followed the crippling siege of the city. Worth, Bullard and Kitty travelled slowly south through England and then tarried in London to await the outcome of the bloody events taking place in Paris, before making their way across the Channel at the end of June 1871. They found a city exhausted and partially in ruins, disordered and vulnerable, but still glamorous in her devastation: a perfect spot from which to co-ordinate fresh criminal activities, with plenty to satisfy the trio’s extravagant tastes. As a later historian observed, ‘France is an astonishingly resilient patient and now – shamefully defeated, riven by civil war, bankrupted by the German reparation demands and the costs of repairing Paris – she was to amaze the world and alarm her enemies by the speed of her recovery.’ Here, Worth saw, were rich pickings. His namesake Charles Frederick Worth, the famed couturier, had ‘bought up part of the wreckage of the Tuileries to make sham ruins in his garden’; now another Worth would also make his mark in the remnants of the devastated city, where, for the time being at least, the authorities were far too busy washing blood off the streets and piecing together the capital to pay much attention to the newly arrived triumvirate.

In later years Kitty would claim, unconvincingly, that she had no idea her husband and his partner were notorious international criminals. It must have been clear from the outset that her charming spouse and his friend were hardly respectable businessmen, since they paid for everything in wads of cash, did no work whatever and never discussed anything approaching legitimate business. Kitty’s part in the next stage of the drama indicates that she was involved in their criminal activities up to her shell-like ears.

With the remains of the money from the Boston robbery, Bullard and Worth purchased a spacious building at 2 rue Scribe, a part of the Grand Hotel complex next to the Opéra, under the name Charles Wells, and rented large and comfortable apartments nearby. The new premises, christened the American Bar, were refurbished in ‘palatial splendour’ at a cost of some seventy-five thousand dollars, with oil paintings, mirrors, and expensive glassware. American bartenders were imported to mix exotic cocktails of a type popular in New York but ‘which were, at that time, almost unknown in Europe’.

The American Bar was a two-pronged operation. The second floor of the building was fashioned into a sort of clubhouse for visiting Americans, complete with the latest editions of newspapers from the USA and pigeon-holes where expatriates could pick up their mail. ‘Americans were cordially invited to use it as a meeting house,’ a spot where they could gather and enjoy American drinks, a quiet, sober and entirely respectable establishment. In the upper floors of the house, however, the scene was rather different. Here Worth and Bullard set up a full-scale, well-appointed and completely illegal gambling operation. By importing from America roulette croupiers and experts on baccarat, they gave the den a cosmopolitan sheen, but it was Kitty who turned out to be the principal lure for ‘her beauty and engaging manners attracted many American visitors’.

Pinkertons’ agents in Europe began keeping a watch on the place almost from the day the American Bar opened, and declared that it was fast becoming ‘the headquarters of American gamblers and criminals who here planned many of their European crimes,’ yet even the forces of the law were dazzled by the ample charms of the hostess. ‘Mrs Wells was a beautiful woman,’ the detectives later reported, ‘a brilliant conversationalist dressed in the height of fashion: her company was sought by almost all the patrons of the house.’ While gorgeous Kitty presided, a vision in silk and ringlets, the affable Bullard played the piano and Worth carefully monitored the clientele. An alarm button was discreetly installed behind the bar ‘which the bar-tender touched and which rung a buzzer in the gambling rooms above whenever the police or any suspicious party came in’. Within seconds of the alarm sounding, Worth could render the upper storeys of 2 rue Scribe as quiet and respectable as the lower ones. The Paris police ‘made two or three raids on the house, but never succeeded in finding anything upstairs, except a lot of men sitting around reading papers, and no gambling in sight’. Worth also bribed the local police to tip him off when a raid might be expected.

The American Bar, the first American-style nightclub in Paris, was an instant success, a gaudy magnet in the ravaged and weary city, and the Parisians were ‘astonished by its magnificence. The place soon became a famous resort and was extensively patronized, not only by Americans, but by Englishmen: in fact, by visitors from all over Europe.’ Businessmen, bankers, tourists, burglars, forgers, convicts, counts, con men and counterfeiters were all equally welcome to enjoy the products of Worth’s superb chef, sip a cocktail, or, if they preferred, repair upstairs where the delightful Kitty would help them to lose their money at the gambling tables with such grace that they almost always came back for more. Word soon spread through the underworld that the American Bar was the best place in Europe to make contact with other criminals, arrange a job, or simply hide out from the authorities.

The elegant and pompous Max Shinburn became a regular patron. Like his former associates, the Baron had found it necessary to relocate to the Continent rather suddenly. Some years earlier, to his intense embarrassment, he had been publicly arrested at an expensive hotel in Saratoga where he was masquerading as a New York banker and charged with the New Hampshire robbery committed in 1865. Police found seven thousand dollars in stolen bonds in his pockets and, on searching his New York address, discovered ‘a complete work shop for the manufacture of burglar’s tools and wax impressions of keys’. Sentenced to ten years, the Baron had managed to escape from prison in Concord after nine months – a breakout considered ‘one of the most dashing and skillful planned in criminal history’ –and had fled to Europe, where his safe-cracking skills were still in great demand. ‘With the money he made from his various burglaries, Shinburn is said to have left the country with nearly a million dollars,’ the Pinkertons reported.

Shinburn had settled in Belgium, purchased an estate and an interest in a large silk mill, and formally declared himself to be the Baron Shindell, which ‘nobody cared to dispute’. His cosmopolitan existence included frequent visits to Paris and the American Bar, where the bogus Baron liked to patronize his former criminal colleagues and spend his money ‘with an open hand’. Worth resented the intrusion of the ‘overbearing Dutch pig’, as he called him, somewhat inaccurately, but tolerated his presence for the sake of Piano Charley, who still owed the Baron a debt for springing him from gaol.

Sophie Lyons, who often travelled to Europe on business (entirely criminal in nature), was another familiar face at the American Bar, and soon a motley cluster of crooks, many of them familiars from the criminals’ New York days, began to orbit around the Paris club at a time when professional American bank robbers were migrating across the Atlantic in increasing numbers. ‘I could name a hundred men who got a good living at it [bank robbery] and then came over to Europe to try their luck. France used to be a particularly happy hunting ground,’ wrote Worth’s friend Eddie Guerin.

Out of the criminal flotsam eddying around Paris, an unscrupulous and unsavoury bunch, Worth would eventually forge one of the most efficient and disciplined criminal gangs in history. Fresh from clearing out the First National Bank of Baltimore, for example, came Joseph Chapman and Charles ‘the Scratch’ Becker. Chapman was a habitual lawbreaker with a long beard and soulful eyes who had, according to a contemporary account, ‘but one vice – forgery; and one longing passion – Lydia Chapman,’ his wife, and ‘one of the most beautiful women the underworld of the 1870s had ever known’. Becker, alias John Blosh, was a neurotic Dutch-born forger of wide renown who was said to be able to reproduce the front page of a newspaper with such uncanny verisimilitude that when he was finished no one, including Becker, could tell the original from the fake. Pinkerton considered him ‘the ablest professional forger in the world’.

Other patrons at the American Bar included ‘Little’ Joe Elliott (alias Reilly, alias Randall), a rat-like burglar of intensely romantic inclinations (‘a great fellow for running after French girls,’ Worth called him), Carlo Sesicovitch, a Russian-born thug with an ugly temper but an uncanny knack for disguise, his Gypsy mistress Alima, and several more criminals of note.

But by no means all the clientele at the American Bar were rogues and miscreants. Many were simply visiting businessmen, ‘swell Americans who were not aware that the keepers of this saloon were American professional bank and safe burglars’, and tourists keen for some nightlife and a flutter at the roulette or faro tables. Their number even included some who had fallen victim to the club’s owners in earlier days. According to one police report, the American Bar was visited by Mr Sanford of the Merchant’s Express Co. while he was in Paris, ‘but Mr Sanford did not know until his return to New York that Wells was the man Bullard, who had robbed the company of $100,000’ back in 1868. It was also said that visiting officials from Boston’s Boylston Bank spent an enjoyable evening at the club, little suspecting how the mahogany card tables and expensive furnishings had been financed.

For three years the American Bar prospered mightily, and the peculiar ménage à trois of the owners continued, amazingly enough, without a hitch. Kitty Flynn, her telltale Irish brogue now quite evaporated, was becoming the gracious grande dame she had always hoped to be, even if half her admirers were thieves and con men. Bullard was happily consuming American cocktails in vast quantities, beginning his day when he opened his eyes in the late afternoon and ending it when he closed them, around dawn, usually face down on the ivories of the club piano. ‘In the gay French capital he soon became a man of mark as a gambler and roue,’ which was all Piano Charley had ever really wanted to be. Worth was also contented enough, though strangely restless. Serving drinks was profitable, while the gambling den was a standing invitation to show his hold over fate, but the Paris operation was hardly the grand criminal adventure he saw as his destiny. The demi-monde thronging his card tables was glittering and amusing, to be sure, but he had more ambitious plans for himself, and Kitty, than merely the life of an upscale croupier and a club hostess.

In the winter of 1873, a most unpleasant blot suddenly appeared on the horizon of the merry trio when William Pinkerton, the scourge of American criminals, wandered nonchalantly into the American Bar and ordered a drink. No man put the wind up the criminal fraternity more effectively than William Pinkerton. The detective had become a stout and florid man, whose ponderous frame belied his astonishing energy and an unparalleled talent for hunting down criminals. Pinkerton’s face was known to just about every crook in America, and so was his record as a man who had ‘waged a ceaseless war on train and bank holdup robbers and express thieves who infested the Middle West after the close of the Civil War’. The direct precursor of the modern FBI, the Pinkerton Agency was gaining international respect as a detective force, thanks in large part to William Pinkerton’s phenomenal energy. The West’s most notable outlaws – Jesse James and his brother Frank, the murderous Reno brothers and the legendary Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid – knew only too well the discomfort of having Pinkerton on their trail. ‘It was not unusual in those bandit-chasing days for William Pinkerton to be days in the saddle, accompanied by courageous law officers searching the plains and hills of the Middle West tracking these outlaws to their hideouts.’ A man of great bonhomie and charm, Pinkerton could also be utterly ruthless, as many criminals had discovered at the expense of their liberty and, in some instances, their lives. ‘When Bill Pinkerton went after a man he didn’t let up until he had got him, if it cost him a million dollars he didn’t mind,’ recalled Eddie Guerin.

Many years later, Worth, in an interview with William Pinkerton, feigned nonchalance when recalling the detective’s unexpected and unwelcome arrival at the American Bar. ‘We were rather troubled at what had brought you to the club,’ Worth said. Frantic would have been a more accurate description.

Worth recognized the burly detective at once and, opting as ever for the brazen approach, offered to buy him another drink. Pinkerton accepted. It was a strange encounter between the arch-criminal and the man who had already spent five years, and would spend the next twenty-five, trying to put him in prison. They chatted awhile on the subject of mutual acquaintances, of which they had many on both sides of the law, until Pinkerton announced that he ought to be getting along. The two men shook hands, without ever having needed to introduce themselves.

The moment Pinkerton had left the premises, Worth summoned Piano Charley and a visiting ruffian known as ‘Old Vinegar’ and set out into the rue Scribe to follow the American detective. ‘There was no intention to assault you,’ Worth later assured Pinkerton. ‘We just wanted to get a good look at you.’ Pinkerton was fully aware he was being tailed and after leading the trio through the streets of Paris for a little way, he suddenly rounded on them. Piano Charley, his nerves frayed with drink, ‘nearly dropped dead’ with fright and the three bolted in the opposite direction. ‘Old Vinegar went into hiding for weeks,’ Worth later remarked with a laugh.

He might not admit it, but Pinkerton’s surprise visit had badly rattled him. Worth was only partially reassured to discover, from a corrupt interpreter with the French police by the name of Dermunond, that the detective was not in pursuit of him and his partners, but was in the pay of the Baltimore National Bank and had his sights set on Joseph Chapman, Charles Becker and Little Joe Elliott. Indeed, the informant warned, Pinkerton was already preparing extradition papers with the French authorities. Worth sent the message to his colleagues that they were in mortal danger and should on no account come to the bar. A few days later Pinkerton, accompanied by two French detectives, walked into another of the gang’s favoured dives, a dance hall called the Voluntino, where Worth was dining with Little Joe Elliott. Worth happened to catch sight of the brawny detective as he came through the door, and rightly assuming the ‘entrances were guarded well’, he bundled Elliott upstairs to a private room, opened the window and, holding Joe’s hands, dropped him fifteen feet into a courtyard below. ‘Joe made the drop alright and got up and hobbled away,’ Worth recalled, but it had been another unpleasantly close escape.

The gang got a welcome, if only temporary, reprieve when Pinkerton was called away to help investigate a series of forgeries perpetrated on the Bank of England. Pinkerton accurately identified the forgeries as the work of brothers Austin and George Bidwell, ‘two well-known American forgers and swindlers’, who also happened to be two of Worth’s regulars. While the Pinkertons were busy chasing the Bidwells (Austin was arrested in Cuba, George in London), Joe Chapman and the others slipped out of Paris and went into hiding.

By now Worth had concluded that the days of the American Bar were numbered. During his brief visit to the club, Pinkerton had correctly guessed that some sort of early-warning system was in place to alert the gamblers upstairs of an impending raid. On his return to the United States he informed the Paris police of this hunch, and began pestering the Sûreté to do something about the nest of foreign criminals flourishing on the rue Scribe. Even the French police, sluggish through bribery, were pushed into action when Pinkerton provided detailed case histories of Worth, Bullard, Shinburn, Chapman, Becker, Elliott, Sophie Lyons and many of the bar’s other regulars. The following May, Worth was again tipped off by Dermunond of an imminent raid and managed to remove all evidence of gambling just minutes before the police burst in. But the attentions of the Sûreté were proving bad for business, particularly among the jittery criminal clientele. ‘The respectable people did not patronize it, and it soon went to the dog,’ Pinkerton recorded triumphantly.

With profits declining, Worth decided to improve matters in his traditional way, by stealing a bag of diamonds from a travelling dealer who had carelessly left them on the floor while he stood at a roulette table. It was a spur of the moment larceny – Worth cashed a cheque for the diamond salesman and distracted him while Little Joe Elliott crept under the table and substituted a duplicate bag for the one containing the diamonds. The theft netted some thirty thousand pounds’ worth of gems, and it was Worth himself ‘who insisted on the police being called in and the place searched from top to bottom. But he did not suggest that they look at a nearby barrel of beer, at the bottom of which reposed the precious jewels’. In spite of this elaborate bluff, the diamond-dealer demanded that the club manager be arraigned on a charge of robbery. At a preliminary hearing Henry Raymond, playing the part of an enraged foreign businessman whose good name was being dragged in the mud, demanded that he be allowed to cross-examine his accuser and so confused the merchant by bombarding him with angry questions that the poor man was unable to remember clearly whether he had had the bag with him in the first place. Worth was released, but the theft, while lucrative enough, sealed the fate of the American Bar.