Полная версия

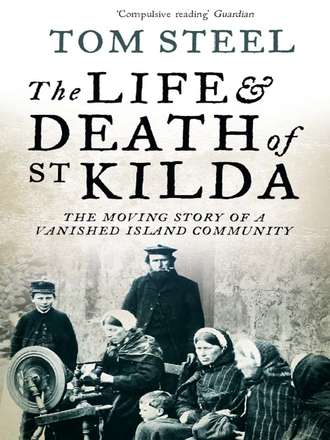

The Life and Death of St. Kilda: The moving story of a vanished island community

The islanders were equally equitable when it came to sharing gifts donated by tourists and well-wishers. All that arrived on the island was divided, just as every St Kildan was prepared to distribute domestic wealth. If the St Kildan sought anything in life, he sought to be fair.

‘The mental constitution or social polity of the St Kildans’, wrote Wilson, ‘consists in their tenacious adherence to uniformity – no man being allowed, or at least encouraged, to outstrip his neighbours in any thing leading rather to his own advantage than the public weal.’ In some respects, the communal system stifled initiative. ‘I myself’, wrote John Ross the schoolmaster in 1889, ‘heard one man expressing a desire to have one end of his house floored with wood so as to make it more comfortable, but he had to give up the idea, some of the others coming down on him with most peculiar arguments leading him to understand the folly of his plan.’ The wife of the last missionary sent to St Kilda recalls: ‘When the St Kildans started doing something, they all did it on the same day. If they killed a sheep, it wasn’t enough for them to kill one sheep for maybe the whole community. No, every house had to kill a sheep. So there was a piece of mutton landed from each house at the manse. You had mutton till you were fed up with the sight of it.’

The socialist system, whatever its faults, was the direct result of the condition in which the St Kildans found themselves. Common survival was the prime concern and although many from the mainland saw fit to criticize the islanders in latter years because, they claimed, the St Kildans lacked initiative, such a human quality was alien to a people who always thought in terms of the whole rather than the part. It was not that the people of Hirta were ignorant, it was simply that the concept of individualism was not applicable, as far as they were concerned, to the set of circumstances they faced.

In the careful ownership of the MacLeods the social and economic structure changed little for over six centuries. But people may have lived on Hirta for possibly two thousand years. The beehive-shaped stone and turf structures in Glean Mor suggest that in prehistoric times a pastoral people may have lived there. Possibly as a result of changes in climate and the lie and content of the soil, they found it necessary to abandon the settlement. Perhaps those early St Kildans were wiped out by disease or forced off the island by those who at the same time or at a later date chose to live in Village Bay. Whatever happened in those early times is unknown, and it is unlikely that the thin, stony soil has many secrets to give up when archaeologists ultimately dig.

In the eighth century the Norsemen invaded Scotland. For four centuries they ruled the islands of Scotland, and lone St Kilda may well have been part of their empire. In 1886, Richard Kearton and his brother Cherry found earthenware pots similar to those used for cooking purposes in Viking times. Many St Kildan place-names, moreover, have their origins in Norse. Oiseval is derived from the Norse austr fell, meaning ‘east hill’; Soay gets its name from Saud-ey, Norse for ‘sheep isle’. In practically all cases, however, the Viking names apply only to landmarks that can be clearly seen from the sea.

The names of those places the discovery of which requires a landing on Hirta are mostly Gaelic in origin. The names of streams and wells, for instance, derive from the ancient language of the Celts. It could therefore be argued that although the island group was known to the Norsemen, they did not permanently settle on St Kilda. It seems likely that the islands were known to them as a place of shelter in a storm and as a source of supplies of fresh water.

The rule regarding place-names, however, is not a hard and fast one. Many names, such as Mullach Bi and Dun, both easily visible from the sea, are Gaelic; one of Hirta’s fresh water wells, Tobar Childa, gets its name in part from Norse. All that can be deduced with certainty is that St Kilda was known to the Norsemen.

Whatever the origins of the early peoples of Hirta, by the middle ages feathers and the oils extracted from sea birds were valuable commodities. To the owner of St Kilda, therefore, the repopulation, or perhaps population of the island, was the result of economic considerations.

The inhabitants of documented times were descended from those who had been born on the adjacent isles of Lewis, Harris, Skye, and North and South Uist. They were, without doubt, Celtic in origin. Although it seems unlikely that the St Kildans were the descendants of ‘pyrates, exiles or malefactors who fled from justice’, as was thought by the Reverend Kenneth Macaulay in 1758, it is probable that MacLeod of MacLeod occasionally sent the discontented to the most remote part of his territory.

The community must have had several injections of new blood during its long history. Some were necessary, others were totally unexpected. Disease practically wiped out the population twice in the history known to us, and the proprietor, anxious to have such a profitable outpost of his estate inhabited, must have encouraged or cajoled crofters from less remote parts of his empire to populate the archipelago. Many ships were wrecked around St Kilda, more visited the islands whilst fishing the rich waters that surround the group and sailors must have taken a fancy to local girls, jumped ship and settled upon the island.

Many writers tried hard to discover physical peculiarities that would illustrate the difference between the St Kildan and the generality of mankind. ‘As a race’, wrote the Reverend Neil Mackenzie in the nineteenth century, ‘the natives now are under-sized and far from being robust or healthy. They are generally of slender form, with fair hair and a florid complexion.’ There is little real evidence, however, that the islanders differed from their neighbours on the Long Island, or that they were less strong. If the St Kildans exhibited any characteristic worthy of note it was that, from an early age, their faces were quick to show the harshness of life on the island. Towards the end of the community’s history, the people seem to have become more susceptible to cuts and grazes, colds and headaches, but their physical prowess did not appreciably decline and any physical deterioration must be attributed to the general decline of the St Kildan way of life.

The personal qualities of the people of Hirta attracted even more attention than their appearance. Apart from their ignorance, which bemused many a visitor, the St Kildans were thought by many observers to be stubborn, superstitious, lazy and greedy. ‘A total want of curiosity, a stupid gaze of wonder, an excessive eagerness for spirits and tobacco, a laziness only to be conquered by the hope of the above mentioned cordials, and a beastly degree of filth, the natural consequence of this renders the St Kildan character truly savage,’ was Lord Brougham’s conclusive description of the average islander in 1799.

The people of St Kilda, however, like those of many primitive communities, possessed remarkable qualities. They were strong of character, and the unique way of living that evolved reflected to a great extent their almost inexhaustible fund of common sense. ‘They are at heart a kindly disposed people’, wrote Nicol, ‘who mean well, and while you are with them you are one of them. They are extremely solicitous for your welfare; indeed those who have lived for some time in their midst say that it is almost embarrassing when they call each morning to ask if you are well, if you have had a good night’s sleep, and if they can do anything for you.’

Like many Celts, however, they were dreamers rather than men of action. They much preferred to talk and could, to the observer at least, always give better reasons for not doing something than they could acquiesce. Many writers took their lethargy to be laziness. ‘I fear’, wrote John MacDonald in 1822, ‘they cannot be exempted from the charge of almost habitual indolence. They are seldom wholly idle; but when they are at any work, one would think that they are more anxious to fill up than to occupy time.’ To the St Kildans, however, the pace of work was dictated by their needs. Time to them was an immaterial dimension divided more into seasons than into months and days. The men in particular saved their energies for the capture of sea birds and did little to help around the croft.

‘The men I always thought might have done more work,’ wrote the missionary’s wife in 1909, ‘although once properly started they worked well. I used to find fault with them for allowing the women to do all the work they themselves ought to have done. It was no uncommon thing to see the young men helping to rope the bags on to the women’s backs. Sheep, coal, or any burden was carried from the pier by the women as a rule – very occasionally the men. I thought it very funny on one of my visits to the village to see the wife digging the ground, preparatory to planting the potatoes, but the good man of the house was seated at the door sewing a Sunday gown for his wife.’ Life on Hirta was such that women were never allowed much leisure. Apart from the routine household chores, the women were responsible for bringing water, fuel, and provisions into the house. Every summer, knitting as they went, the women used to walk over two miles twice a day to milk the cows and ewes in Glean Mor. Whilst boys were soon taught the art of talking much and doing little, the girls were accustomed to carrying heavy weights on their backs from a very early age.

The morals of the St Kildan and his spouse, however, could not be faulted. Crime was virtually unknown on the island. In a society in which each and every member had to get along with his neighbour in order to survive, crime could not be tolerated. Moreover, there was a distinct lack of motive – each islander was the same in terms of both wealth and status as his fellow St Kildan. ‘I held, along with Mr McLellan and the Gaelic teacher,’ wrote John MacDonald in 1822, ‘a meeting, something like what might pass in St Kilda for a justice of peace court, in order to settle little differences that might exist among the people; and was pleased to find, much to their credit, none of any consequence, except one relating to a marriage.’ St Kilda was totally free from the ‘bend sinister’, the morality of the men being even more unimpeachable than that of the women. There was little drunkenness. When a St Kildan had whisky to drink, it was reserved for medicinal purposes, or put away in a cupboard to celebrate a marriage. ‘Their morals’, concluded the Reverend Macaulay in 1758, ‘are and must be purer than those of great and opulent societies, however much civilised.’

The islanders were intensively religious. Their fervour was in part induced by their physical situation. A sea-girt isle, rising almost perpendicularly from the sea, with nothing save the often fierce Atlantic in sight, St Kilda presented man with almost insurmountable odds. Under such conditions of geography and climate, Man became even more infinitesimal before the Infinite. The people took for their own a harsh, puritanical religion, which gave them a peace of mind and offered them, if not a future on this earth, at least a pattern which they could follow and a promise of a more certain life in the next world.

As contact with the mainland increased during the nineteenth century, the St Kildan character developed in some respects detrimental to the reputation of the people. ‘A St Kildan woman’, wrote Kearton in 1886, ‘always regards everybody with suspicion, and does not hurry over a purchase, thinking that she is being cheated.’ The islanders were a simple, honest people: the tourists were more sophisticated and from a society in which it was the common thing to seek to take advantage. The St Kildans were incapable of adapting to a more complex set of rules of behaviour and became introverted. Nor did they distinguish between tourists and those who came to their island to do genuine good. Doctors found themselves faced with resolution and stubbornness. ‘There is no need’, wrote Norman Heathcote in 1900 of the St Kildans, ‘for them to go through the form of saying that they are conscientious objectors. They simply refuse to allow their children to be operated on, and there is no more to be said.’

To the end, the St Kildans possessed a simplicity that was at once attractive, if infuriating. When Emily MacLeod, the sister of the then proprietor, told the St Kildans in 1877 that she like Queen Victoria was a plain old woman, she was sternly rebuked by the islanders, who informed her that she must not refer to Her Majesty in such a way, as the Bible said that subjects must honour their monarch. When a supply of cement was sent to St Kilda so that a proper aisle could be laid in the Church, the ‘bags of dust’ as the islanders called them were stacked outside the Church to await a time when the men could see their way to doing the job. The following summer a friend of the proprietor arrived to ask how the work had gone. The ‘bags of dust’, said the men, had by a miracle all turned into lumps of rock before they had got round to using them.

Whatever their faults, the St Kildans led an unenviable way of life. The provision of food was their major concern year in and year out. They were forced to make good use of everything that their poor island could offer them in the struggle for survival. Moreover, they lived in the knowledge that any part of the provisioning process could be disrupted at any time by weather and illness. Isolated from the rest of humanity, only the laird of Dunvegan was there to protect them from starvation.

4

Bird people

Boys on St Kilda were taught to climb cliffs as soon as they were able. ‘The first thing to attract our notice’, wrote John Ross the schoolmaster of an August day he spent in a boat at the foot of the cliffs of Conachair, ‘was one of the men and his little boy on a rugged but fairly level piece of ground rather down near the sea. One end of the rope was tied round the father’s waist while the other was tied round the boy’s waist. Most probably, lest he being young, rash and inexperienced, might slip into the sea. There they were all alone then, killing away at a terrible rate, for the boy was collecting while the father kept shaking and twisting.

‘The man removing himself from the rope shouldered a burden of dead fulmars and made for a cutting in the rock, too narrow one would think for a dog, and too slippery for a goat. Along this he crawled on hands and knees. A single slip in the middle would have hurled him at least eighty feet sheer down into the sea. But he landed his burden safely and returned for the boy. The rope was tied as before, but only about a yard was left between them this time and that brave little fellow of only ten summers fearlessly followed his father and reached safety without a hitch. This is how the St Kildans train their young to the rocks and what a dangerous life it is.’

The St Kildans learnt how to climb from childhood. Most of them remember playing on the cliffs of Conachair when they were young and thinking nothing of it. They grew up to be short, stocky, agile men, natural climbers. The bone structure of their ankles differed from that of people born elsewhere. The ankle of a St Kildan male was practically half as thick again as that of a mainland person, and the toes were set further apart and almost prehensile.

The slaughter of sea fowl for food was essential to life on St Kilda. What the reindeer is to the Laplander, so the gannets, fulmars and puffins that each year made their nests on the cliffs of the rocky archipelago were to the St Kildans. Due to the poverty of the soil, other forms of subsistence were incapable, on their own, of maintaining human life on Hirta. The islanders had their sheep, a few cattle, and a meagre crop of potatoes, barley and corn, but without the flesh of the sea birds they could never have survived. Totally cut off from the rest of society, they were only able to live on their island by denying themselves the way of life common to crofters in other parts of Scotland and becoming, as Julian Huxley remarked, ‘bird people’.

‘The air is full of feathered animals,’ wrote John MacCulloch when he visited St Kilda in 1819. ‘The sea is covered with them,’ he continued, ‘the houses are ornamented by them, the ground is speckled with them like a flowery meadow in May. The town is paved with feathers…The inhabitants look as if they had all been tarred and feathered, for their hair is full of feathers and their clothes are covered with feathers…Everything smells of feathers.’

The sea birds and their eggs were jealously guarded by the St Kildans. In 1695, a boatload of strangers attempted to steal some eggs from the cliffs. The St Kildans fought off the intruders and put the precious eggs back in their nests. For good measure the islanders confiscated the pirates’ trousers before sending them on their way. During the nesting season, the single egg laid by the fulmar was not allowed to be removed for eating. Steps were taken to prevent the sheep and dogs from worrying the birds. Every June, the St Kildans fenced off the cliff tops with ropes made from hay with feathers stuck into them, so vital was it to the community that the eggs be allowed to hatch. When Parliament at Westminster passed an Act for the Preservation of Sea Birds in 1869, acknowledgement was made of the islanders’ dependence upon their feathered itinerants. A clause was inserted excluding St Kilda from the provisions of the Act because of ‘the necessities of the inhabitants’.

For nearly nine months of the year, the St Kildans were preoccupied with the killing of sea birds. ‘From their dependency on the capture of sea fowl for their support,’ wrote George Atkinson, ‘all their energies of body and mind are centred in that subject and scarcely any of their regulations extend to anything else; from the period of the arrival of the fowl in the month of March, till their departure in November, it is one continued scene of activity and destruction.’

Puffins in their hundreds of thousands were the first birds to return in March after a winter at sea. Most of them made for the island of Dun, and the St Kildans lost little time in seeking out the first fresh meat they had had the opportunity to taste for nearly four months. The adult gannets would begin to come back at the end of January, but it was not until April that the islanders would launch the boats to go to Stac Lee and Stac an Armin to kill the birds. During the month that followed, gannets and puffins continued to provide the people with food, and the fulmars nesting on the ledges of the cliffs of Conachair offered a welcome change of diet. Although the fulmar eggs were never taken from the nest because the female laid only one, those of the gannet and the guillemot were taken in their thousands. The St Kildans ate them fresh, or preserved for consumption at some later date, in the knowledge that the female of those species would replace the stolen egg.

June and July were lean months as far as sea birds were concerned. The puffin was the only bird available for eating while the young gannets and fulmars hatched and grew. The harvesting of fulmars took place in August when the young birds would be killed in their thousands before they could leave the nest. The young brown-feathered gannets, or gugas as they were called, matured more slowly, and it would be a month later before the men would take to the boats and rob the stacs of the birds.

When Martin Martin visited St Kilda in 1697, he estimated that 180 islanders consumed 16,000 eggs every week and ate 22,600 sea birds. From Stac Lee alone, he reckoned, the St Kildans took between five and seven thousand gannets annually. A century later an observer calculated that nearly 20,000 gannets were harvested each year on Stac Lee and Stac an Armin. In 1786, over 1,200 gugas were taken from their nests in a single expedition.

In the nineteenth century, however, the number of gannets killed declined. No more than 5,000 birds were taken each year in the first half of the century. By 1841, the catch had dropped to an average of 1,400 a year, and after the turn of the century only about 300 young gannets were killed and preserved for winter eating by the St Kildans.

As early as 1758, the islanders claimed that the fulmar had begun to replace the gannet as the staple of their diet. The reasons for the change were probably many. There was a sharp increase at that time in the number of fulmars breeding upon St Kilda, and the feathers and oils of the bird were of great value to the proprietor. Until 1878, St Kilda was the only breeding colony of the fulmar petrel in Great Britain, and the MacLeods may well have wished their tenants to exploit the situation. Centuries of decimation, moreover, may well have laid the great stacs almost bare of gannets. Robbed of its eggs as well as its young, the colony of solan geese had probably decreased.

The ratio of fulmars killed per inhabitant remained fairly steady throughout the island’s history. During the years 1829 to 1843 when the population of St Kilda stood at about 100, an average of 12,000 fulmars was slaughtered every year, which divided out meant 118 birds for every inhabitant. In 1901, by which time the population had fallen to 74, the harvest numbered some 9,000 birds, which meant that each islander was consuming some 130 fulmars annually. Even in 1929, the year before the evacuation, the last harvest comprised some 4,000 carcasses, an average of 125 per inhabitant.

The diet of the St Kildans was based on the flesh of these sea birds. Breakfast normally consisted of porridge and milk, with a puffin boiled in with the oats to give flavour. Until the end of the nineteenth century, the people disliked wheaten food and fish, and ate mutton or beef only as a last resort. The main meal of the day, taken at about lunchtime, comprised potatoes and the flesh of fulmars.

Nearly all food on Hirta had to be boiled or stewed. There were no ovens on the island, save the range that was the proud possession of the minister in the manse. To the outsider, food tasted rather bland, and a lack of proper fuel meant that it was usually under-cooked and never served very hot. ‘When boiling the fulmar,’ wrote John Ross, ‘they sometimes pour some oatmeal over the juice and take that as porridge, which they consider very good and wholesome food which I have no doubt it is to a stomach that can manage to digest it.’

The flesh of the fulmar is white. In the older birds, it is a mixture of fat and meat, while the young birds are nearly all fat. When cooked, the fulmar tasted somewhat like beef, and Heathcote, having eaten a meal with the St Kildans, remarked, ‘I must say that we were agreeably surprised. We had expected something nasty, but it was not nasty. It was oleaginous, but distinctly tasty.’

If the fulmar was tasty, it was also tough – good for the St Kildans’ teeth and gums. Ross noted that at the time of the fulmar season, the whiteness and strength of the inhabitants’ teeth improved. Dental care was never to be a problem worthy of note on Hirta, in spite of the fact that toothbrushes were non-existent. Eating the flesh of fulmars, puffins, and gannets seems to have preserved the islanders’ teeth.

In the summer months, the puffins were the main source of food. Mrs Munro, the wife of the last missionary, remembers how they tasted when she tried to cook them. ‘The first lot of puffins (of the season) were brought by the postmaster. They were all dressed, ready for cooking. I asked Nurse Barclay how to cook them and she said put them in the oven and roast them. My husband was in school and came home to dinner and he said, “Try them”. I said, “No thanks, I’ve had enough – I’ve roasted them.” I went to empty the tin and each time I emptied it nothing but oil would come out till you got fed up with seeing it.’

‘The gannets we ate’, recalls Neil Ferguson, ‘tasted fishy and salty.’ Like the fulmar, the gannet was normally salted down for eating in winter. Ferguson recalls: ‘You had to steep them in water for twenty-four hours to take the salt out of them, and then boil them with tatties for your dinner.’ The guga, in fact, was not a food peculiar to St Kilda: the birds were regarded by some on the mainland as delicacies and were regularly served by ships’ cooks on the steamers that plied the Western Isles.