Полная версия

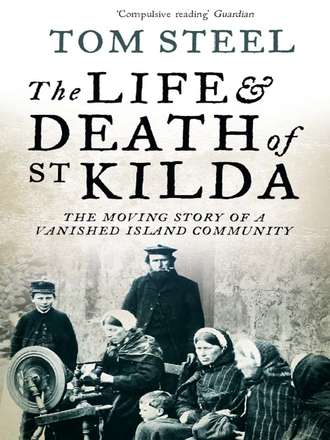

The Life and Death of St. Kilda: The moving story of a vanished island community

For the greater part of St Kilda’s history, however, communication with the mainland was as sporadic as it was unnecessary. The community was self-sufficient, relying only upon the visit once or twice a year from a representative of the island’s owner to collect rent and deliver a few essential supplies, such as salt and seed.

3

The paternal society

Feudal society existed in Scotland centuries after it had disappeared elsewhere in Britain. The Celtic people who inhabited the most northerly remote parts of the British Isles were thought to be of little consequence by the Anglo-Saxons who dominated British society. The Celts were therefore allowed to carry on living the way they had always done. In most of northern Scotland the social system was ruthlessly destroyed after the 1745 Jacobite Rising, but in the more remote parts of the Highlands and in the Western Isles the old order lived on.

Enlightened paternalism was the basis of the society of the Gael. The Chief who owned the land also ruled over the people who lived upon it. As long as the Chief acted as a good and wise father and the crofters settled on his estate were respectful children, feudalism proved itself to be a successful as well as convenient way of managing society. If the critics of the more ‘civilized’ South thought the feudal system of the Celt was primitive, it could at least be seen to be a social organization that worked and worked well for hundreds of years. In the words of Dr Fraser Darling in West Highland Survey, Gaeldom is ‘an example of a culture finely adjusted to an environment which placed severe limitations on human existence’.

The people on the lone isle of Hirta were throughout their history part of the old order. Until the evacuation in 1930, the proprietor of the island group, MacLeod of MacLeod, not only owned St Kilda but held sway over its inhabitants. He was father as well as landlord, and as such received for himself and his house the greatest of respect and affection. ‘Their Chief is their God, their everything especially when a man of address and resolution,’ wrote Lord Murray of Broughton in a report on the Highlands he drew up in 1746 for the London government. The duty of the Chief was to protect his clan, administer good and impartial justice when settling disputes that might arise among his people, and above all hold his land so that his people might live and prosper upon it. In return the crofters would offer their services to fight for any cause deemed just by the Chief, and give him absolute claim over any produce deriving from the croft.

Although the Gaelic word clann means ‘children’, the system did not depend upon the people working the land being of the same family or even the same name as the owner. On St Kilda no inhabitant was related to MacLeod of MacLeod by ties of blood near or remote. The few families whose surname was MacLeod were like all the other families – they were descendants of the poor from other parts of the Chief’s estates who were encouraged to take up crofts on St Kilda. The concept of kinship played little or no part in the clan in the wider sense. What bound the people together was a shared feeling of loyalty to the Chief whose land they held, and mutual understanding between him and his people.

MacLeod of MacLeod, Chief of Clan MacLeod, owned St Kilda throughout most of its inhabited history. When and how the family gained possession are questions the answers to which are lost in time. Legend has it that at one time both Harris and Uist disputed ownership of St Kilda. Even in ancient times the island group was regarded as a jewel in the Atlantic that any laird would be proud to own.

A race was planned to settle the question of ownership. Two boats representing the contending interests were rowed out to the island by crews of equal size. It was agreed before the start that the first crew to lay a hand on Hirta would claim it for his Chief. The race was extremely close, and as the two boats neared the island the stout men of Uist were ahead. Colla MacLeod, head man of the Harris boat, cut off his left hand and threw it ashore in a last desperate attempt to win the island for his master. The loss of a hand was not in vain, and St Kilda was won for MacLeod of MacLeod. This noble deed, some would have it, is recorded for posterity by the red hand on the clan coat of arms.

The MacLeod of MacLeod was an island Chief with an island empire. As such he tended to be too remote to become involved with the politics of the mainland to the same extent as the Campbells or MacDonalds did. Although many MacLeods, for instance, fought at the battle of Culloden, they did so against the wishes of their Chief who had little heart for the Jacobite cause.

After Culloden, the policy adopted by the Hanoverians was aimed at obliterating the Celtic way of life. ‘In Scotland more than elsewhere,’ wrote Grant, ‘into the purely feudal relationship had crept something of the greater warmth and fervour of the ancient bond of union of the clan (or family)’, and the government was determined to put an end to such dangerous feudalism. The Disarming Act was revived and important additions made to it. The wearing of Highland dress and the use of tartan were prohibited, and the playing and even carrying of bagpipes was forbidden. The bans were to last thirty-six years and dealt a damaging blow to a people’s culture. In 1747, Parliament passed an Act for the Abolition of Heritable Jurisdictions which took away from the Chiefs their legal powers. After Culloden many Highland estates were forfeited.

The victors, however, did not take vengeance upon the laird of Dunvegan. He had played a passive part in the rebellion and, besides, his estate was remote and fragmented. MacLeod of MacLeod held on to his lands and the patriarchal rule of Dunvegan was allowed to continue well into the nineteenth century.

The economic buttress of the Chief’s hold over his people was the system of trading by barter. Every year a representative of the Chief would visit St Kilda to claim the rents in kind. Often the ‘tacksman’, as he was called, was related if only distantly to the Chief. He leased the island from the proprietor for a sum of money or was given the revenue of the island as a reward for performing some special service.

When Martin Martin visited St Kilda in 1697, he did so in the company of MacLeod of MacLeod’s representative. While on the island the steward and his retinue, which often numbered forty or fifty people, were housed and fed at the expense of the islanders. He would go once a year to the island in the summer and stay for anything up to two or three weeks. The ancient Gaelic due of free hospitality to the Chief or any of his household was known as cuddiche and was exacted in St Kilda when it had long disappeared elsewhere. Cuddiche was similar to the right to hospitality demanded by medieval and Tudor monarchs in England when they made their royal progresses.

At the end of his stay on St Kilda, the steward or ‘tacksman’ would take back to Skye the oils and feathers of the sea birds and the surplus produce of the islanders’ scant crofts. The goods would either be sold to tenants who lived on other parts of the Chief’s estates or else sent south to the commercial markets. Part of the proceeds of their sale would go towards the St Kildans’ rent, and part would be retained by the tacksman as profit. But he had to fulfil his obligation to the islanders. A good part of the money obtained by the sale of the island produce was used to purchase commodities such as salt and seed corn which the St Kildans had need of. Supplies of essentials that the island could not provide were normally transported to St Kilda the following summer, or else delivered later the same year should the people be in dire need of them.

For centuries the system worked admirably. Hirta’s exports were in much demand on the mainland, and the island was a source of profit for the tacksman and proprietor alike. According to Lord Brougham in 1799, the tacksman paid £20 a year to MacLeod of MacLeod and reckoned to make twice as much himself. The barter system, however, benefited the people of Hirta. No one would have claimed that the islanders received a true market price for their goods, but on the other hand they did not need to bother themselves with finding outlets. In bad years they never went without essential supplies. It was in no one’s interest that the St Kildans starve. A loss to the tacksman one year would no doubt be turned into profit the next.

An islander, called the ground officer, was appointed by the Chief to speak for the community should differences of opinion arise with the steward. If the difference was serious, it was the ground officer’s duty to make a personal appearance before MacLeod of MacLeod himself to air the complaint. ‘He makes his entry very submissively,’ wrote Martin Martin, ‘taking off his bonnet at a great distance when he appears in MacLeod’s presence, bowing his head and hand low near the ground, his retinue (usually the crew that had rowed him over from St Kilda) doing the like behind him.’ MacLeod of MacLeod would then listen solemnly to the evidence and pass judgement. Few disputes, however, came about regarding the management of St Kilda. The tacksmen for the most part were ‘Gentlemen of benevolent dispositions, of liberal education and much observation’ (John Knox).

The Chief rarely failed to exercise what was seen as a moral responsibility towards his people. During the last quarter of the eighteenth century, MacLeod of MacLeod ceased to receive any money from his estates for a while. ‘This estate’, wrote Knox in his Tour Through the Highlands of Scotland and the Hebride Isles, which was published in 1787, ‘has been greatly diminished of late years on account of debts, and much remains to be discharged. Notwithstanding this circumstance, the proprietor raised no rents, turned out no tenants, used no man with severity, and in all respects maintained the character of a liberal and humane friend of mankind.’ In 1780 the proprietor supplied the St Kildans with a new boat, and although salt was heavily taxed at that time and was virtually unobtainable in many districts of the Highlands, the people of St Kilda still received their more than adequate supplies.

Life on the mainland, however, was changing, and MacLeod of MacLeod suffered drastically from the changes, being forced to sell much of his estate. Tacksmen became people of the past, and what remained of the estate of the Chief of Clan MacLeod was henceforth managed by his factor at Dunvegan. St Kilda forever held an affectionate place in the history of the MacLeod family and was not sold.

The last factor was John Mackenzie of Dunvegan, an amiable man fond of St Kilda and its people. Once a year it was Mackenzie’s duty to go to Hirta and collect the Chief’s rents. Dressed in a long tweed trenchcoat and rarely seen without a gamekeeper’s deer-stalker hat, Mackenzie was much liked by the islanders. He would spend most of his time on St Kilda having long conversations with them, listening to their problems and attempting to solve them while on the island. If that was not possible, he would see what could be done after he had returned to Dunvegan. To the St Kildans, the factor was the go-between. He was their real link with the outside world.

One of the major tasks of his visit would be the landing of the stores he brought with him on board the Robert Hadden. Such work was normally done by the women, supervised by the men of the island. One of the most important things he took with him was a cask of paraffin, which was invariably given to the islanders as a gift.

The ceremony attached to the annual payment of rent always remained the same. The St Kildans would gather outside the old storehouse down by the shore, and once their produce had been inspected by the factor the bartering would begin. As fair a price as possible would be bargained by both sides – in later years it proved less and less favourable to the islanders. During the twentieth century the payment of rent was less a reality and more a symbolic act. During the thirteen years prior to the evacuation, the islanders failed to raise enough produce to pay rent due on their crofts. In John Mackenzie’s day, the only produce of any real value was tweed, a few stones of dried ling, and perhaps a sheep or two. The end of the annual rent ceremony was marked by the factor presenting sweets to the St Kildans, instead of the traditional presentation of Highland whisky with the receipts. The St Kildans never kept account of what they handed over to the factor: there was trust on both sides.

The introduction of money, however, did more than all the vengeance exacted after Culloden to destroy traditional Gaelic society. Crofting, the most prominent feature of the Highlanders’ way of life, was proving to be extremely uneconomic. The coming of the Industrial Revolution and the payment of money in exchange for labour was drawing people away from the country. It was no longer possible to think in terms of payment in kind. The barter system was no longer relevant or tenable. Money was required for the purchase of foodstuffs and materials essential to the maintenance of life upon the island and the cost involved in the transportation of those goods; both factors conspired to render a fatal blow to the old social order. The St Kildans, like other Celts, were forced to accept modern society and its values or else be condemned to oblivion.

From time immemorial the men and women of Hirta governed their lives as best suited their lonely predicament. ‘Their government is strictly a republic,’ wrote George Atkinson in 1831, ‘for though subject to Great Britain, they have no official person among them; and as they are only visited twice a year for a few days by the Tacksman, who is referred to as a sort of umpire or settler of disputes, their knowledge of our laws must be very trifling and of little use or importance in their system of economy.’

The community as a whole shared the responsibility for the two major tasks: to ensure that every islander was fed, clothed, and housed as was thought proper, and to provide sufficient wares to pay the proprietor his rent. All possessions, such as boats and ropes, upon which the safety and prosperity of the community depended, were therefore held in common. Authority over the actions of every islander was vested in what tourists were later to call ‘Parliament’.

Every morning after prayers and breakfast all the adult men on the island met in the open air to discuss what work was to be done. In latter years, the men met outside the post office, every day except the Sabbath. In so small a community, where the normal pursuits of its members were so fraught with danger, it was important that all knew what was planned, and a meeting was a sensible way of letting everyone know where members of the community could be found during the rest of the day. ‘It wouldn’t do to go away on your own,’ recalls Lachlan Macdonald, ‘and the other fellows didn’t know where you were going. So they always decided where they were going and what they were going to do that day.’

It was a simple way in which a people who thought and acted in terms of each other could communicate as a group. The St Kildan Parliament, however, came in for criticism from outsiders. ‘The daily morning meeting’, wrote John Ross, the schoolmaster, ‘very much resembles our Honourable British Parliament in being able to waste any amount of precious time over a very small matter while on the other hand they can pass a Bill before it is well introduced.’ But the islanders themselves would have been the last to think of their assembly as capable of great, philosophical thought. As far as they were concerned, the morning meeting was the only way, in a land that lacked telephones and newspapers, of letting others know what was planned, what was believed, and what was to be done.

If it was a ‘Parliament’, it was one that perhaps met the needs of those it served better than any other. There were no ‘headmen’ in parliament. Every islander had an equal right to speak, and to cast an equal vote. It was an assembly that had no government. There was always a total lack of distinction upon St Kilda. No islander held sway over his fellow islanders. Equally, no rules governed the conduct of the morning meeting. The men arrived in their own time, and at the meeting, according to observers, everyone appeared to talk at once.

If the proceedings of the day were important, the morning meeting would waste little time. If a visit to one of the neighbouring islands or stacs to tend the sheep or kill the sea birds was in order, the men would be quick to get to the work at hand. If, however, there was little of urgency that required to be done, the meeting could and would often sit all day in discussion. A break for lunch would be taken as and when the proceedings allowed, but otherwise talk would be the work of the day. ‘Upon the whole,’ wrote John Ross, ‘the St Kildans are just as much engaged as their crofter neighbours in the Outer Hebrides and although they do at times spend much more time than is necessary over “parliamentary” affairs, they often derive benefit from it inasmuch as any stray piece of useful information picked up by a single individual is imparted to the whole.’ The adventures of those who had had the opportunity to visit the mainland were related in great detail to the assembled throng. Information such as the cost of buckets and spades in the great metropolis of Glasgow and what wonderful shops were to be found there were not the only subjects of great interest. The most important function of the morning meeting was the exchange of views and the sharing of experiences.

The St Kildans never regarded themselves as individuals. Each and every one was a component of a community. The daily meeting was that which held them together, even though ‘Parliament’ was often the market place of gossip. ‘Very often,’ said Ross, ‘“my neighbour” and anything he has done out of the way, whether it is right or wrong’, were matters to be examined by the assembled islanders. Discussion frequently spread discord, but never in recorded history were feuds so bitter as to bring about any permanent division within the community. Perhaps the fact that criticism was aired so readily ensured that gossip was never allowed to get out of hand.

The laws that governed the island were equally of the people’s own making. Although formally subject to the law of the rest of Scotland, there was never an instance when those laws were either enforced or needed to be. ‘Murder, of course, from the impossibility of escape and the absence of the usual causes of incitement is unknown in their traditions,’ wrote George Atkinson, ‘and dishonesty from similar causes very nearly so; a case of adultery has never been known among them, and as no fermented or spirituous liquor is made on the island, and they only receive a trifling half-yearly supply from the Tacksman, they are of necessity sober.’

The St Kildans looked to the Bible for their laws. In most respects they abided by the laws laid down by Moses in the Old Testament. How such a corpus of law became embodied in the community is unknown, but Macaulay in 1758 probably correctly believed that missionaries must, at an early date, have converted the St Kildans to accept such a code of behaviour.

Only the elders of the Church had authority over the rest of the community. They were responsible for sharing out the produce of the islanders’ labours equally. Should there be any difficulty, the distribution would be settled by lot. The division of native labour was always carried out to the satisfaction of all concerned. After the harvesting of the sea birds, the catch of each day was placed in one great heap, usually on the foreshore, and was then divided out according to the number of households on the island. ‘At the end of the day’s fowling,’ wrote Christina MacQueen at the time of the evacuation, ‘the sharing began. Grouped around the large heap of slain fulmars stood the representatives of every family. In the rear the women and juveniles waited; waited to carry their portion to the cottage, where the plucking would immediately begin. The larger the family, the bigger the share. There was no such thing as payment by results. Such a practice is only necessary where the thing, miscalled “civilization” has blunted the natures of men, and made them selfish and callous, and brutal to their fellows.’

The sick, the young and those who were old and lived alone were always cared for. ‘The St Kilda community’, remarked Wilson in 1841, ‘may in many respects be regarded as a small republic in which the individual members share most of their worldly goods in common, and with the exception of the minister, no one seems to differ from his neighbour in rank, fortune, or condition.’ The St Kildans throughout their history never included either ministers, missionaries, nurses, or schoolmasters in the sharing out of their food, be it the carcass of fulmar, gannet, or sheep. They were always regarded as outside the community. All received a part of the community’s produce as a gift; none of them ever received a share as a right.

Like every system of sharing, there were exceptions to the general rule. Any St Kildan, for instance, who killed a young fulmar or gannet ‘out of its nest’ was allowed to keep the bird for himself. The justification for such an exception was that if he had not taken the bird, it would either have died a natural death or have been swallowed up by a raven or a crow. By 1880, the fulmar and the puffin were the only birds subject to equal division. By that time, apart from homespun tweed, their feathers and oil were the only staples used to pay the rent, a concern always regarded as the responsibility of the community as a whole.

All the grazing for the sheep that each St Kildan kept was held in common. The island of Dun was the only grazing that was subject to conditions. The lush clover grass that covered the island was strictly reserved for wintering the young lambs, and because of the island’s size, only a certain number of sheep could be accommodated. An islander was able to keep as many sheep and cattle as he was able to pay rent for, and the number of lambs that could be transferred from Hirta to Dun every year was decided equitably by the morning meeting.

A mutual insurance scheme operated in St Kilda. Any islander who had the misfortune to lose sheep during the winter or during the time when they were rounded up for shearing was reimbursed by his fellow St Kildans in proportion to the number of sheep the latter possessed.

The island’s boats were throughout history owned and maintained by the community at large. Boats were essential to the island’s way of life: it was only right, therefore, that everyone be concerned with their condition. Each islander was made responsible for the upkeep of a section of the boat, and its use was determined by the morning meeting. No islander or group of islanders was able to make use of the craft unless everyone had given his permission. Should foolhardiness mean the community lost its boat, then life would be impossible. It was only right, therefore, that its employment be decided by consensus.

The St Kildans carried equality into every aspect of their lives. When the Highland and Agricultural Society sent out meal and flour to the people every year, the distribution of the supplies was always strictly regulated. Each male and female over eleven years of age on the island was entitled to a full share; islanders between the ages of nine years and eleven were entitled to three parts of a share, and from cradle age to under nine every St Kildan was entitled to a half share.

A man’s share equalled one boll, which was the equivalent of 140 pounds of flour or oatmeal. After the supplies were distributed, anything left was given out to each household in shares applicable to smaller quantities.

The supplies of tea and other commodities brought to the island by the factor were distributed in a similar way. Potatoes, for instance, were shared on the same basis as meal and flour. Only sugar was an exception. An equal share was given to both young and old, and if preference was ever exercised it was in favour of the younger members of the community.

In later years, the division was calculated more simply. One share was allotted to each adult islander and a half share was given to children of sixteen years and under.