Полная версия

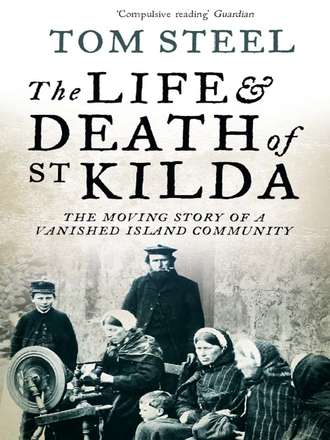

The Life and Death of St. Kilda: The moving story of a vanished island community

The Life and Death of St Kilda

The Moving Story of a Vanished Island Community

Tom Steel

Updated by Peta Steel

Dedication

This book is dedicated, as Tom Steel would have wished,

to the memories of the St Kildans. It is also dedicated to

the memory of his father, Tom Steel Snr, who worked on

the first edition of this book with his son and was

responsible for introducing him to St Kilda.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Map of St Kilda

Prologue

Introduction

1 Exodus from St Kilda

2 A World Apart

3 The Paternal Society

4 Bird People

5 Life on the Croft

6 God and the Devil

7 The Far-Flung Dominie

8 A Chance to Turn a Penny

9 A Cause of Death

10 A Need to Make Contact

11 The Beginning of the End

12 The Changeless and the Changed

13 God Will Help Us

14 Morvern and Beyond

15 Military Occupation

16 St Kilda in Trust

17 Of Mice, Men and Other Life

18 A Far Better Place

Postscript

Tom Steel’s Acknowledgements for the 1988 Edition

Bibliography

Searchable Terms

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Praise

Copyright

About the Publisher

Map of St Kilda

Prologue

‘I have a St Kilda in my mind, an island haven reminding me,

“You are a Scot. Do not forget that fact”.’

Tom Steel, ‘Notes on St Kilda’

Tom Steel died on 21 July 2007; he was sixty-three years old. Tom first wrote ‘The Life and Death of St Kilda’ when he was a student at Cambridge. It was published by the National Trust for Scotland in 1965, and subsequently by Fontana in 1975, with a new edition in 1988. When he died, Tom had been working on material for an update to the 1988 edition. The Postscript to this book is based on those notes, and goes on to include what has happened to St Kilda since 2007.

The destiny of St Kilda has been defined largely by two events. The first was on 29 August 1930 when its inhabitants were evacuated. The other was in 2005 when St Kilda received a second UNESCO World Heritage Site designation, making it the only Dual World Heritage site in the United Kingdom.

Although official recognition from the UN of St Kilda’s natural, marine and cultural significance should give it protection from oil exploitation, vandalism, fishing hazards and damage to its wildlife and terrain, there is little legally that the responsible authorities, which include UNESCO, the European Union, the Scottish Parliament and the UK government, can do to safeguard the islands. Tom believed the future safety of St Kilda would lie in its at-times-inaccessible position. The seas and the weather of St Kilda remain as much a threat to visitors as they have always been. Shipwrecks still happen and access is often cut off.

There is a moral obligation to ensure that the National Trust for Scotland, which owns and manages the islands on behalf of the Scots and the rest of the world, receives the financial and public support to enable it to protect St Kilda. Therein lies a dilemma. The Scottish Parliament has a ‘right to roam’ policy, one which is endorsed by the NTS, whose own open access strategy encourages people to visit its properties. The NTS needs to raise the islands’ profile to attract visitors and funds to enable it to maintain a presence. At the same time, it has to guard against too many visitors causing damage to the environment, which has happened at other World Heritage Sites such as Macchu Pichu, the Galapagos Islands, and the Cairngorms in Scotland.

In 1930 the departing St Kildans left their doors open believing that no one would ever live on Hirta again. In August 2010 there were thirty-six people on St Kilda, exactly the same number as had been present eighty years earlier. These were the new ‘St Kildans’ – wardens, members of conservation and archaeological work parties and MOD personnel. In 1988 Tom Steel wrote: ‘Many from the mainland have now experienced what it is like to live on Hirta and it is interesting to compare and contrast our modern reactions to the problems posed by nature. Men now live on St Kilda for different reasons and in a totally different way: but their experiences, nevertheless, and the draw that the archipelago has on our minds and hearts, are worthy of investigation.’

Lessons are still being learnt from what happened to St Kilda and to its inhabitants. The islands have been subjected to intensive scientific, historical and archaeological surveys, which may help answer many questions. The constant search for information will, one day, however, draw to an end, leaving the archipelago to return to the wild.

St Kilda continues to affect those who visit it, read or see films about it. The contribution of the stories of the St Kildans and their music is now seen as integral to Gaelic culture. But to Tom, the story of St Kilda was essentially that of its people; a civilization that came to an end because it was more expedient for the authorities to move them rather than give support and enable them to stay. As people examine their lives and relationship with nature, far more is being done to ensure that other such populations faced by extinction remain on their islands. The evacuees always referred to their love and desire to return to St Kilda. ‘It was a far better place,’ as Malcolm Macdonald once explained to Tom.

Tom Steel first visited St Kilda when he was seventeen, his interest being stimulated as a boy by his father who made several trips to St Kilda on National Trust cruises. The spell that the islands and its people cast on him was to last for the rest of his life.

Introduction

St Kilda is the most spectacular of all Britain’s offshore islands. The main island of the group, Hirta, boasts the highest cliffs and the largest colony of fulmars in Britain. The neighbouring island of Boreray and her two rocks of Stac Lee and Stac an Armin are the breeding grounds of the world’s largest colony of gannets. The little archipelago, in fact, is a land of superlatives and as such has always fascinated the minds of men.

But the greatest fascination is that for over two thousand years man lived upon St Kilda. On the island of Hirta people once led a unique and unchanging way of life. They were crofters, like most of their neighbours in the Hebrides, but crofters with a difference. Cut off from the mainland for most of their history, the islanders of Hirta had a distinct way of living their lives. Isolated from the majority of the Scottish people the St Kildans were forced to feed upon the flesh of the tens of thousands of sea birds that returned year after year to breed on the rocky islands. Moreover, their very self-sufficiency meant that throughout their history they possessed a sense of community that was to show itself increasingly out of place.

It is not easy to imagine the lonely life led by the St Kildans. It is difficult for us to accept that they had more in common with the people of Tristan da Cunha than they ever had with the city dwellers of Edinburgh or Glasgow. Any similarity between the St Kildan way of life and that led upon the mainland was superficial. Isolation had a determined effect upon their attitudes and ideas. The St Kildans can only be described as St Kildans and their island home little else than a republic. The people, like those of most isolated communities, sacrificed themselves year in and year out securing, often precariously, a livelihood for themselves and their children. In the practical business of living, St Kilda bore little relation to the mainland where people were becoming more concerned with evading secondary rather than primary poverty. When the island was finally evacuated in 1930, not only had Nature defeated man but, in a real sense, man had defeated his fellow men.

Now, over fifty years after the evacuation, the whole story can be told, and in particular what happened to the St Kildans after they decided to abandon Hirta and settle on the mainland of Scotland. It was not until 1968 that the records of the Scottish Office pertaining to the 1930s were made available to public examination. In the Public Records Office in Edinburgh lie more than two dozen files that once were the property of the Department of Agriculture. From the collection of letters, minutes, and memoranda can be gleaned the true tragedy of the evacuation – not only the human distress involved, but the parsimony and bureaucratic behaviour of the civil servants concerned in the event – behaviour which makes one question whether they can ever be capable of true compassion.

The evacuation of St Kilda was to illustrate the basic insecurity of the society that had developed on the mainland of Scotland. It was an insecurity that showed itself when faced with a seemingly small and insignificant community such as was found on Hirta. It was thought that if the St Kildans could not adapt and accept the values of the dominant society, the only solution was to bring about a state of affairs which would result in evacuation. In this sense, the British government’s obsession with the costs involved in providing the St Kildans with a nurse and a postal service mirrored the feelings of a society that not only demanded money should not be wasted in such a way but, more importantly, would not accept that anomalies may, let alone should, exist.

Throughout most of the last century, St Kilda was subject to pressures. Education, organized religion and tourism all attempted to throw into doubt the St Kildans’ way of life. For centuries the world outside stood aloof from the people of Hirta. They were content on the mainland to allow such a remote community to go its own way. As long as the people of St Kilda were so isolated, they were insulated from the forces that wished them to conform. The strength of the community, however, became weakened as contact with the mainland increased. When disease decimated their number and wind and sea made the acquisition of adequate supplies of food difficult, the St Kildans were forced to turn eastward for help.

The majority of books written about St Kilda appeared during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The authors for the most part were products of the buoyant and vital society of Victorian and later Edwardian Britain – a society in which it was generally thought that man could do little without doing good. The writers felt it was their duty to help others less advanced (and therefore less fortunate) to attain the civilized level of their own society. Help, as interpreted by the articulate spokesmen of a richer and more advanced society, was best given by persuading the islanders to give up the struggle.

In 1930 the people of Hirta unwittingly threw themselves into the twentieth century. As adults, they had to accept those values that most of us on the mainland are taught to believe in from birth. For instance, the islanders found it difficult to base their existence upon money. They had never lived in a world in which they bought goods and services of each other. They had of course accepted gladly the opportunity of making a little money for themselves at the expense of tourists, but that intrusion had never altered the basic relationship one St Kildan had had with another.

The islanders showed themselves indifferent to the jobs they were given on the mainland. The labours asked of them were menial contrasted with the spectacular feats they had once performed in order to kill sea birds. Moreover, the slaughter of fulmars and gannets directly determined whether the community on Hirta had enough food to survive. When they worked on the mainland, the St Kildans realized that the tasks they performed did not supply them immediately with what was needed to keep them fed and warm. On the mainland, the islanders worked for money. Money was necessary in order to purchase from others the things necessary to life. Between the employment of their skills and survival came a state of affairs that we all take for granted.

The history of the St Kildans after the evacuation, of their inability and lack of resolution to fit into our urban society, makes sad reading. If St Kilda had been an isolated home, the islanders were to discover that the remote district of Argyll in which most were settled was even more alien. On Hirta at least they had formed a tightly-knit community with a common purpose. When they were resettled on the mainland, the St Kildans were forced to live in homes miles apart from each other, in a society whose values were unacceptable if not incomprehensible to the majority of them.

The history of the St Kildans shows the folly of thinking of the islanders as similar to ourselves, and their community but a distant cousin of our vast urbanized society. The death of St Kilda was to prove the most important in the history of island depopulation in Scotland. The publicity the evacuation received brought home to government and public alike the hazards involved in seeking to solve the problems of isolated communities by simply evacuating them.

When, in 1936, a government committee examined the economic conditions of the Highlands and Islands, the members concluded ‘that in view of the present trend towards concentration of population in the larger cities and industrial centres, the full development of an area such as the Highlands for the building up of a strong, healthy, virile race must be regarded as being of vital importance to the nation, and for this reason, if no other, we feel justified in making recommendations involving expenditure’. During the last world war, in fact, the county of Inverness provided more soldiers than any other county in Britain. It was not unemployment alone that forced men into service: the battle honours of both world wars read like the roll-call of the Battle of Culloden.

To this day, however, a large and often influential section of our society demands that communities which cannot support themselves should be similarly dealt with. The history of mankind, it seems, must of necessity be a continual process of the inhabitation and evacuation of areas that for a time suffice man’s needs. In terms of Britain, the Highlands and Islands of Scotland have been sacrificed in order to advance civilization.

The story of the life and death of St Kilda is perhaps more pertinent today than it has ever been. Our industrial society has forced people to contract relationships with each other on the basis of money. Money is what binds individuals together and fixes the relationships they have with each other. Opulence in the modern Western world has become the yardstick of human happiness and it has been widely accepted that men should always strive in search of economic wealth unless ignorance, poverty, or sheer habit prevent them from doing so.

We are presently faced with the pressures and problems that the money motive has helped create. The poverty of urban industrialized life and the human stress that is now showing itself in practically every Western industrialized society call into question the basis upon which our society is founded. More recently, the energy crisis, problems of pollution and monetarism have altered the rate at and method by which society seeks to advance itself. Given our present crises, however temporary they may prove to be, it is natural that we doubt the goal of our endeavours. The story of St Kilda may be a small human tragedy, but the study of the islanders’ former ways and the reasons why the people were forced to evacuate their island might provoke some to question our future.

1

Exodus from St Kilda

Wednesday 27 August 1930 was overcast for most of the day on St Kilda. Shortly after dawn a raw mist slowly rolled over the Atlantic from the nearby island of Boreray and spilled over the cliffs on Conachair like a waterfall. By the afternoon a thick, grey blanket hung low over the village. It was cold and damp – so unlike the summer days of the previous week. Few on the island, however, had time to notice that the weather had changed. The St Kildans had much to do if in two days’ time they were to leave the island forever.

In House no 5, Main Street, St Kilda, Annie Ferguson was busy at her spinning wheel. She was preparing yarn for a length of cloth that a tourist from the mainland had asked her to make. She would not finish the work, that she knew; but she would take the yarn to the mainland with her and in the coming winter months her husband would weave the tweed on the old loom they were taking with them.

In the other room of the house a young newspaperman was finding it difficult to pen his copy. Alasdair Alpin MacGregor, then thirty-one, had been sent all the way from London by The Times to report on the evacuation. As he sat close to the small window to catch the falling light, the paper he was writing on became wet in the heavy atmosphere. He struggled on, knowing he would have to wire his story as soon as he boarded the SS Dunara Castle.

On the advice of Nurse Williamina Barclay, the St Kildans had decided to take with them only those few possessions that could be of use to them in their new life. All through the day, heavy bundles were carried from the houses to the jetty. The women were busy packing kists with the few clothes and heirlooms each family possessed. They were also packing the wool taken that summer from the island sheep. It would be a waste to leave it behind; it could prove to be a useful source of income. Even in their new homes the St Kildans could knit and weave as they had done for generations to help supplement the new reward for their labour called wages.

Down by the old storehouse, used for over a century by the St Kildans to lay aside the produce they had bartered with those on the mainland, a few of the men were busy sawing up bits of wood. They were concerned to protect the few pieces of furniture being taken away from becoming damaged in transit. With battens and rope they made safe the tables and chairs that were to be transported to Lochaline in Argyll. Others were occupied at the back of the manse, sifting through the driftwood that had been cast ashore over the years. Much of the wood was the cargo of a freighter torpedoed off St Kilda in 1917. The big planks of timber, the men agreed, might be of use; they too would be loaded onto the Dunara Castle, due to arrive at St Kilda that day.

To the right of the schoolhouse, about a hundred yards from the jetty, the remainder of the St Kildans’ sheep were bleating in the calm air. Six hundred and sixty-seven sheep had already been transported by the SS Hebrides to the marts of Oban on 6 August. In July the Scottish Department of Agriculture had sent out an official and two shepherds from Uist along with their dogs to help the islanders round up their sheep. The task had not been an easy one. Many sheep had gone over the steep cliffs rather than be captured; many like those on Boreray had to be left undisturbed because taking them off proved impossible, given the time and manpower resources available.

To begin with, the St Kildans had stubbornly refused to help gather their scattered flocks. It had been suggested that the money obtained from their sale should go towards paying for the evacuation of the community. The islanders felt that if the government wanted to remove the sheep, they could do the work. One islander, old Finlay Gillies, had gone as far as to take to his bed the day before the rounding-up was due to begin, claiming that he was too sick to get up. The missionary Dugald Munro suggested to Macaulay, the Department’s representative, that the situation might be eased if the government offered the St Kildans money in exchange for their help. When the islanders heard that they would be paid a pound a day, even Finlay Gillies was seen catching sheep along with the rest of the men among the cliffs. Removing the sheep from St Kilda proved a costly business. It cost the government over £240 to transport twelve hundred sheep to the mainland, plus £143 in wages and expenses for the shepherds. By the time the sheep had been dipped and penned at Oban until their sale on 3 September, the total cost was £506 os 4½d.

At five o’clock in the afternoon the island dogs announced the arrival of the SS Dunara Castle. As she steamed like a ghost ship through the heavy mist into the bay, the islanders dragged their boats down the slipway into the water to go out and meet her. There was the hope of a last letter from friends on the mainland, eager to wish them well, and the chance to sell to the thirty or so visitors on board the few remaining socks and scarves the women had knitted. The last tourists to visit the island inhabited hoped to buy a spinning wheel or some other relic of life on St Kilda from a people only too eager to be rid of them. They were to be unlucky. The island had been stripped of most souvenirs in the few weeks since the world had got to know that St Kilda was to be abandoned. When the visitors had been rowed ashore, the St Kildans returned to the most pressing business of the day – the transfer of the sheep.

They had arranged the sheep in groups so that they could be loaded more easily into the boats that would take them out to the Dunara Castle. There were over five hundred sheep to put on board. It was a slow, tiring business; to and from the steamer, the islanders plied boats that could hold no more than a dozen sheep at a time. It was not until after nine o’clock in the evening that the majority of the sheep were safely on board. By then it was getting dark and dangerous to do much more; the few lanterns cast little light on the operation and the jetty was crowded with tea chests and bits of furniture. But work continued, and it was not until one o’clock in the morning that the nine fit men on the island struggled for over an hour to pull the boats up the slipway clear of the high-water mark.

At approximately three o’clock in the morning ‘The Books’ were brought out, and in the house of the Fergusons, Alasdair Alpin MacGregor joined in the day’s last act of reverence to the Almighty. After a few verses of a psalm to the tune ‘Wiltshire’, ‘The household’, wrote the man from The Times, ‘was so tired that we contented ourselves with a short reading and a shorter prayer. In the small hours we dragged ourselves to bed knowing that at daybreak we had to resume the shipping of the sheep.’

At first light the St Kildans were awakened by the siren of the SS Dunara Castle. The crew were anxious to complete the work and return to the mainland. After breakfast and family prayers, the St Kildans once again pushed their little boats into the water and took the last of the sheep on board. Then came the turn of the cattle, which had to be enticed down to the jetty with handfuls of soda scone. The four young calves were rowed over to the waiting ship in one boat, whilst the cows, tethered to the tail of the small craft in case they drowned, had to swim. The last ten cows of St Kilda were taken over to the Dunara Castle and hoisted aboard.

At approximately seven o’clock in the morning of 28 August, HMS Harebell, under the command of Captain Barrow, steamed into the bay. She had been sent by His Majesty’s Government to carry out the evacuation of the islanders. The Harebell, the senior ship of the Fishery Protection Squadron, had spent the summer months touring the fishing ports of the British Isles. The ship had left Oban and crossed to St Kilda during the night. ‘We knew we were due for this,’ recalls Commander Pomfret, then medical officer on board, ‘so we had fitted it in.’