Полная версия

The Garden in the Clouds: From Derelict Smallholding to Mountain Paradise

There was no shortage of interest. The bidding flicked rapidly upwards. Soon it narrowed down to me and a small, sharp-eyed, fox-faced man with a peaked cap pulled well down over his eyes. By the rubber overalls under his shapeless tweed coat, I was pleased to note he was a hill farmer rather than a restoration enthusiast, so presumably wouldn’t have absurd amounts of money to spend. £1,160…£1,180…£1,200…I could feel my pulse quickening. My adversary looked shrewd, informed, sure of himself. If he wanted the Fergie, it was plainly a good buy so it would be doubly foolish to miss out. £1,220…£1,240…My opponent’s face was a mask. He communicated his bids by tiny, almost imperceptible nods, hardly more than twitches. £1,360…£1,380…£1,400…Would the man never give up? How much did these hill farmers have tucked away? The auctioneer sensed my wavering. ‘Go on, Sir, you’ve come all this way’—(where did he get that idea?)—‘Not going to lose her for a couple of quid, are you?’

‘£1,500,’ I said crisply.

He turned to my adversary. ‘He’s way over his limit, Sir. I think you’ve got him.’

Another expressionless twitch. The auctioneer turned back to me. ‘Come on, Sir. You know it’s got your name on it.’ The crowd was loving it. Well, suffice to say, I got her. In the adrenaline rush it seems I also bought Lots 572, 573 and 574, the all-important pulley wheel, assorted bars and links that Jonny had announced went with the Fergie, and a complicated-looking hay mower with scissor blades that looked like a big hedge trimmer. As the crowd moved on, and the Fergie was again deserted, I sat on its front wheel in a daze of mixed emotions: happy fulfilment (I owned a tractor!), guilt (the purchase was indefensible), trepidation (what was I going to tell Vez? How did the thing work?). My father looked nonplussed. ‘How much was it?’ he said. ‘What ever will you do with it?’

Jonny climbed onto the Fergie and pressed the starter. Nothing happened. ‘Notoriously bad starters, Fergies,’ he said. He fiddled with various switches and levers and tried again. Again, nothing. ‘That’s odd,’ he said. He ordered me into the driving seat, while he tinkered in the engine. I was instructed to press a button in with my right ankle, while pressing the gear lever forwards. ‘Are you sure this is what you do? It doesn’t sound very likely.’ I was told I knew nothing and just to do as I was asked. It made no difference.

‘It started a minute ago. There must be something you’re not doing.’

But there wasn’t. Or there didn’t seem to be. The crowd had moved well away by this time. Did I catch a frisson, a lightning backwards glance towards us, from my foxy friend in the low peaked cap?

An hour passed. People started arriving in pick-ups with trailers to collect and load their lots. We buttonholed any likely looking person who wandered past. They leant under the raised bonnet. They pored over the engine. They prodded and poked. They said Fergies were notoriously bad starters. But everyone agreed, it all looked fine. The field began to empty. My father went home. As I drove back to Tair-Ffynnon to look for tools for Jonny to start dismantling the engine, the full idiocy of what I’d done sank in. It had never occurred to me that the tractor might not work. In the excitement of the auction I hadn’t given a thought to any practicalities. I knew not the first thing about tractors. I was amechanical. What was I to do next time she wouldn’t start? Call the AA?

A couple more hours passed while Jonny dismantled and reassembled the engine. It made no difference. At length, he puffed out his cheeks. ‘Well, I don’t know what’s wrong. Everything works fine. It should start.’ By this time, the field was almost empty and a steady drizzle was falling. We were saved by an old boy wandering by. He told us to check a tiny lever hidden out of sight on one side of the engine. Somehow it had mysteriously moved from ‘ON’ to ‘OFF’. ‘I think someone’s played a joke on you,’ he said.

It was months before we finally got the saw-bench rigged. After a rudimentary course of tractor-driving instruction, Jonny departed, leaving me to make jerky, undignified forays up and down the track, trying to master the clutch. This tended, however gently it was engaged, to snatch, catapulting the machine forwards in ungainly kangaroo bounds. Vez, presented with my sly fait accompli, was magnificent, even agreeing the tractor looked just so, and made us appear less like urbanites (an accommodation assisted, unquestionably, by an envelope from my father which arrived a few days after the auction containing a cheque for the price of the Fergie and a fairytale about finding more money in an account than he’d expected).

From a company Jonny told me about (‘A & C Belting’), I ordered a rubberized canvas belt and the next time he visited, we heaved the eye-poppingly heavy bench into position, pegging it into the dirt floor of the barn with eighteen-inch iron pegs.* Then Jonny oiled and greased the blade shaft and pulley wheel spindles. With much to-ing and fro-ing, we positioned the tractor. We chocked the wheels and connected up the pulley belt between the tractor and the saw-bench. We engaged the tractor’s pulley wheel, setting the belt turning. Then I pulled the iron lever on the saw, which slid the belt across to drive the blade. The saw cranked into life.

It was simply terrifying. I’d never been so close to a machine that was so blatantly lethal. The belt flapped and slapped between the pulley wheels, hungry to snag any loose clothing or inquisitive passing child. The blade whirred and squeaked like a giant bacon slicer, though the sound was quaintly soothing and almost musical: the rattling rhythm of the Fergie’s engine, the regular ting-ting of the staples in the belt as they passed over the iron pulley wheels. I found some small branches and pushed them towards the blade to warm it up (something the man from A & C Belting had advised). The saw scarcely noticed. After a few of these I pushed a thick old stump forwards with a stick. The blade screamed as it bit into the wood, and the tractor engine chugged harder, reverting to its gentle clatter as the cutting finished, the blade ringing as the severed timber thudded onto the ground. The smell of sawn wood filled the air. It was sensational.

Wood was strewn all over the place at Tair-Ffynnon: shambolic heaps of logs and stumps, hedging offcuts, old fence posts, sections of telegraph poles and sleepers, as if a giant had been playing Pick-Up Sticks before being called away mid-game. To at last be clearing it was satisfying work. Some timber cut more easily than others. Yew and old oak were so hard their sawdust was as fine as flour. Sappy larch and fir released a delicious piny smell, but the resin gummed the blade, making the belt slip. As my confidence increased I discarded my stick, pushing the logs forwards by hand. Occasionally, with the scrap wood, the saw would hit a nail or a staple, screeching and sending out showers of sparks. Soon the iron table top shone and the feet of the bench were lost in deepening heaps of sawdust that dusted every surface like snow.

True, I couldn’t quite banish the image of a gross-out, splatter-movie death. A momentary lapse of concentration, a trip from catching my foot on something buried beneath the sawdust, and—the wood chipper scene from Fargo or Johnny Cash’s brother in Walking the Line. My hand, or arm (or head) in the log pile. But the tangle of timber was transmogrifying into a neat pile of logs for splitting. And all that fear worked up a prodigious appetite.

Maybe stockpiling wood is in our genes as hunter-gatherers. Stacked wood bespeaks security, cosiness, preparedness for winter. Perhaps it’s because it’s exercise with a purpose, or a way of clearing one’s head. ‘I chop wood,’ Gladstone told the journalist William T. Stead, ‘because I find that it is the only occupation in the world that drives all thought from my mind.’*

Maybe it’s all the associations that come with an axe: the forest clearance, the ancient oaks of England on which a navy and an empire were built. Or the perfection of its form. If an hour’s wood-chopping is soothing work, it must be because quite so much hopping around, swearing, trying to extricate the wedged head has taken place over the 1.2 million years of steady R&D devoted to this, the prototypical tool. Though in fact it’s not a tool, it’s a simple machine, using leverage to ramp up the force at the cutting edge, and dual-inclined planes to enhance the splitting action. That head is drop-forged from medium carbon steel (the flaring cheeks averaging twenty-nine degrees): hard enough to hold an edge, yet not so brittle it shatters. The shaft (of ash or hickory so it won’t splinter or split from the strain) is kinked for easy swinging by anyone of average height. And it’s a philosopher’s axe—not a rake or broom—over which we puzzle: is it still our grandfather’s if our father replaced the head and we the shaft? The Director of the British Museum recently called the axe ‘the most successful piece of human technology in history’.

Not bad for twelve quid from Homebase.

5 Winter on the hill

A glance around at the landscape should have warned us what we were in for. Where rowan and hawthorn trees bend at permanent right angles, man wasn’t meant to plant Jerusalem artichokes and rhubarb.

ELIZABETH WEST, Hovel in the Hills, 1977

‘Was Granny’s garden in the Yellow Book?’

‘It was.’ My father could compress much meaning into two words.

‘At Rookwoods?’

‘At Rookwoods. And again when she moved to Bath. She was very much the magnanimous charity worker, remember’ (that was pretty loaded, too). I’d been sporadically quizzing him about the National Gardens Scheme since hatching my plan, but it had only recently occurred to me that Rookwoods itself might have been in the Yellow Book.

‘And…?’

‘Well, it was the kind of menace you might imagine. We all had to dance attendance and ended up doing most of the work. On one occasion she announced she was going on holiday the week the garden was opening, leaving us to take care of it. You can guess how well that went down with your mother.’

‘So you helped, too?’

‘We all had to help.’

‘Didn’t it occur to you to mention this?’

‘Mention what?’

‘The fact that Granny was in the Yellow Book? I’ve been asking you about the Yellow Book for weeks.’

‘No. You never asked that.’

It was July and our move to the sheep-run pastures of Tair-Ffynnon was complete. We’d driven over to the Mendips for one of our periodic Sunday lunches with my father. He greeted us with his usual mock exasperation. ‘Late as ever.’

‘You’d be disappointed if we weren’t.’

He gave me a bottle of champagne to open. He always gave us champagne when we came now: a reminder how special these occasions were, and how seldom we saw each other since my brother and I had young families. Today, however, I had a private purpose in coming. If I were going to make a garden I needed to learn all I could about gardening—fast. It was so vast a subject it was hard to know where to begin, and my father seemed a good start. My mother may have been the botanist, but the garden of our family home was very much his. So I did something I’d never done before: I requested a garden tour.

I regretted it almost immediately. Full of pre-Sunday-roast bonhomie, we’d hardly carried our glasses to the low raised bed outside the kitchen—‘This, as you know, is the Eucryphia…it has the most wonderful big flowers in August’—before the first pang of deep boredom set in. It wasn’t what he was saying so much as what it brought back. Suddenly I was at Stourhead, aged seven, standing on aching legs by some tree or other, while my parents banged on and on about it. And it wasn’t just Stourhead. It was Hestercombe, Barnsley House, Prior Park, Westonbirt Arboretum…all names whose mere mention made me thankful never to have to be a child again.*

With specialised interests, opposite characters and very different backgrounds, my parents ostensibly had nothing in common. The garden was the closest they came. ‘This, as you know…’ my father’s voice brought me back to the present. ‘…is the Philadelphus. It has the most glorious scent…’ Then there were the Latin names. I could almost hear my mother shouting from the kitchen window: ‘Behind the Eucryphia…No, you noodle, the Eucryphia, not the Euphorbia…’ I didn’t discover plants even had English names until my mid-twenties. As academics of the pre-spin school, my parents never seemed to feel the need to make their subjects interesting or accessible, to supply context or simplify.

My father had now moved on to explaining his principles for choosing plants, his preference for foliage over flowers, but it was hard to separate the information from the associations. ‘This is Rhus cotinus. Another shrub you grow only for its leaves…’

‘What are these, again?’

‘Stachys lanata.’

‘Do they have an English name?’

‘I think some people call them Lamb’s Ears.’

It struck me that going round a garden with its owner is not unlike looking at someone else’s holiday snaps at their pace. (‘That’s Jackie, the person I was telling you about. She was so funny.’) Yet, having specifically requested the tour, I could hardly ask to speed things up.

We walked back up the lawn, past the kitchen, and up the steep path towards the open fields behind the house. The garden wasn’t large, perhaps a quarter of an acre, but it was much divided around the house because of the way the site had been bitten out of the hill-side.

‘Did Ma help much with the garden?’

‘Did she actually do anything, d’you mean? Heavens no. She was far too busy with her horses. Full of advice, of course. Sometimes she used to “pop things in”, as she called her cuttings. She was extremely tiresome in that regard.’

As we returned to the front door, we encountered something I could confidently identify. ‘Purple sage,’ I said.

‘Mmm…herbs.’ The word was invested with a scorn it’s hard to convey in print.

‘Why, don’t you like herbs?’ I knew perfectly well what his views were on herbs, and the reasons he’d give for them, but I couldn’t stop myself.

‘They’re a nuisance.’

‘A nuisance? How can herbs be a nuisance?’

‘You have food that tastes of nothing but herbs, rather than what it’s supposed to taste of.’ For my father, cooking was a chemical experiment: instructions were followed, tasting was unnecessary and final temperature (piping hot) was the key indicator of the success of the meal.

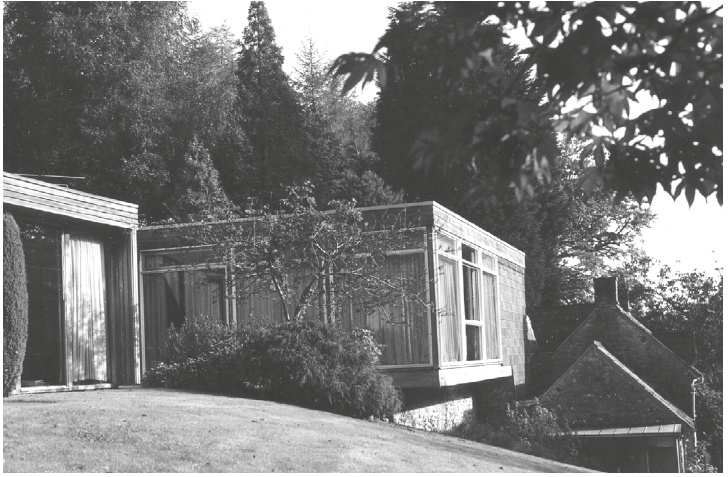

We had to go back into the house to reach the patio. The house was my father’s Great Modernist Experiment, the product of his love of architecture in general and Mies van der Rohe’s 1929 Barcelona Pavilion in particular. In time for my arrival in 1963, they needed to add onto my mother’s cottage, which had only one bedroom and a wide landing where Jonny slept. My father devised a contemporary solution. Modules precision-machined off-site by Vic Hallam, the Nottinghamshire company made famous by its pre-fabricated classrooms, were bolted to a pre-formed, cantilevered concrete deck. Twenty-eight polished Ilminster stone steps led up from the poky cottage’s front door to an airy, light-filled, flat-roofed glass box, containing sitting room and bedrooms. These were furnished accordingly: razor-edged steel-and-glass coffee table, brick-hard, angle-iron and foam-rubber Hille sofas, Ercol bentwood table and chairs. Comfort took a holiday. And so Modernism made its brazen progress from Bauhaus Germany, via New York, to our ancient Mendip lane. Nothing like it had been seen before in rural Somerset.

The patio arrived in Phase Two of the Great Modernist Experiment, an extension forced upon us by my mother’s riding accident almost a decade later. It was my father’s most successful garden space, enclosed on three sides by the house, and on the fourth by the rising ground of the hill. It was, as he’d intended it, an astonishing suntrap. In raised dry-stone beds he’d planted acers, a green one with broad leaves and a couple with more dissected leaves in red and bright green. I ran my hand along one of the smooth, shapely branches. After thirty years the trees were sculptural, contributing a calming, vaguely Japanese air to the space that set off the severity of the square brutalist concrete pond and the glass and cedar of the house.

During the Modernist years, my father had maintained the pond, with its floor of raked pea shingle, in a state of stark clinical perfection, washing it clean of algae several times a summer so the water never clouded. But in later years he’d given up, planted lilies in the corners, stuck a round stone bowl in place of the water jets and even, the final capitulation, added goldfish. It was softer now, but less dramatic or coherent.

I wanted another drink and for the trip to conclude. We took the path round to the back of the house, north-facing and enclosed by a conifer plantation. Towering into the sky, straight as a missile launcher, was the tree with my favourite name.

‘There you are: Metasequoia glyptostroboides.’ My father pronounced it perfectly, slowly, with just the right amount of ironic inflexion to wring out its full, polysyllabic absurdity. ‘It’s a remarkable tree,’ he said. ‘One of the few in the country when we planted it. Your mother got hold of it through some botanical thing she was doing. Looks ludicrous now, of course, it’s got so big.’

It wasn’t the only giant. Blocking the view in or out from the lane was a stand of three vast leylandii.

‘What possessed you to plant those?’

‘It’s all very well for you to be sniffy about them now, but at the time they were the wonder tree. We’d never come across anything like them. Fast-growing. Dense. Evergreen.’ He sighed. ‘But they do grow like triffids. I’ll have to take them out.’

Was any of this remotely useful or relevant for Tair-Ffynnon, I wondered? We went in for lunch. Midday sunshine streamed through the south-facing floor-to-ceiling glass, the same glass that on winter nights used to seem so cold and black and endless (and still makes me yell at wide-eyed couples on Channel 4’s Grand Designs as they order their steel and glass boxes: ‘Don’t do it! You’ll feel cold and vulnerable and watched! You’ll spend a fortune on curtains and ruin the look!’). Four candles on wall sconces in the dining room, comically drooped and corkscrewed, testified to the opposite extreme. But today, with the doors open, the house was perfect: warm and light and airy.

After lunch, while Vez, pregnant with our second child, lay snoozing on the sofa, and my father played songs on the piano for Maya, I ransacked my mother’s bookshelves, as Uncle William had advised. Here were floras and herbals, catalogues and regional guides. Many of the names were familiar: Hillier’s Manual of Trees and Shrubs and H. J. Bean’s doorstop volumes of Plants and Shrubs Hardy in the British Isles (a title which for some reason always conjured images of plants swathed in brightly coloured cagoules and scarves battling up a hill), though I’d never opened them before. And I now saw, as I pulled a few out, what a wise course this had been. It would be hard to devise books more calculated to repel a potential plant lover. All appeared to share the same striking characteristic: not a picture to be seen. I was puzzled because these volumes, I knew, were mere holiday-reading, lightweight warm-up acts, alongside the vade mecum of my mother’s day-to-day existence: the much-thumbed Flora of the British Isles, which I now pulled out. Its cheerful yellow jacket, with a picture of a flower, was at iniquitous odds with the 1,591 pages of closely written print within. This was the immortal ‘Clapham, Tutin and Warburg’, named after the three distinguished professors of botany who were its editors. Each entry matched absolute incomprehensibility with mildly pornographic lang uage. A sample might run:

Basal sinus wide, coarsely dentate; cauline lvs. Pedicels erect, with small sessile glands. Densely tormentose with pickled, blue-veined spectricals. Sparsely ciliate on the petiole. Stipules and peduncles fili form indehiscent. Sepals lanceolate-aristate, hairy. Petals obovate cuneiform. Carpels pubescent. Naturalised in North America. Endemic.

Was this, I wondered, why places seemed so much more interesting than plants? Alongside Clapham, Tutin and Warburg, the architectural jabber wocky of my father’s Pevsner’s county-by-county Buildings of England series (another collection for which a few more pictures might not have gone amiss) read with Orwellian clarity.*

Further meditations were interrupted by the soothing, familiar rattle of my father bringing the tea tray. Tea was an inviolable 4.15 tradition in the Woodward household (equal mix Lapsang and Earl Grey, minute, much-stapled tea cups, and, when she was alive, one of my mother’s cakes). As Vez stirred and sat up, and Maya hurled herself at my legs, I wrenched my thoughts from stipules and peduncles.

That summer was the record-breaking one. Back at Tair-Ffynnon, it seemed as if clouds had become extinct. Exchanging our hard-won London pad for a derelict hilltop smallholding seemed the cleverest move we’d ever made. We bought a big army frame tent (big enough to accommodate a Land Rover) to act as a spare room for friends to stay in. It came in two vast canvas bags, so heavy the delivery driver and I could only just move them. The military instructions specified at least five to erect it (‘pitching party—five men’) so we did it one day when friends came for lunch. We weighted the wide ‘mud cloths’ with concrete joists and breezeblocks and whacked in two dozen enormous iron pegs with a sledgehammer. Then, inside, we decked it out, until, frankly, it was the cosiest room about the place.

We’d got a new black Labrador puppy (christened Beetle after her propensity for eating dung) and twice a day I’d walk up to the trig point with her. The place bustled with activity. During the day there were walkers and riders, bemused school orienteering parties, pony trekkers, runners, mountain bikers, radio modellers, occasional motocross riders (on plateless scrambling bikes and always careful not to remove their helmets). Gliders would fly down the ridge, almost brushing the bracken, so close you could hear the air rushing over their wings. There were falconers, racehorses exercising from the local yard, whinberry pickers with faces and fingers stained purple-black. Walkers would stop to ask for water, or, exhausted, if we could drive them to their B&B. And when we heard muffled shouts and bright canopies billowed up on the far side of dry-stone walls, we’d know the wind was from the east. Then dangling figures suddenly appearing out of the sky would drive Beetle into paroxysms of territorial barking, a remit she soon extended to anyone wearing a backpack, rendering our walks a good deal less relaxing for all concerned.

But as evening came, calm would descend; the hill would empty, until the moment when it was deserted apart from the swallows. After all the bustle, the quiet seemed twice as intense. Day after day dawned cloudless and warm, some so clear and still that, in the way that silence amplifies space, the sky seemed twice the size. Far above us, vapour trails dispersed like gradations on some vast protractor. Stonechats arrived, their characteristic call like two stones smacking together. At ground level, the forests of thistles left by the sheep went to seed, sometimes filling the air with so much thistledown it seemed to be snowing. A red start nested in the baler. As the hill got drier and drier, the ponies brought their foals to drink at the bathtub in the yard.