Полная версия

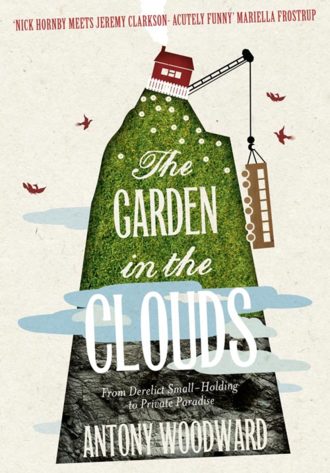

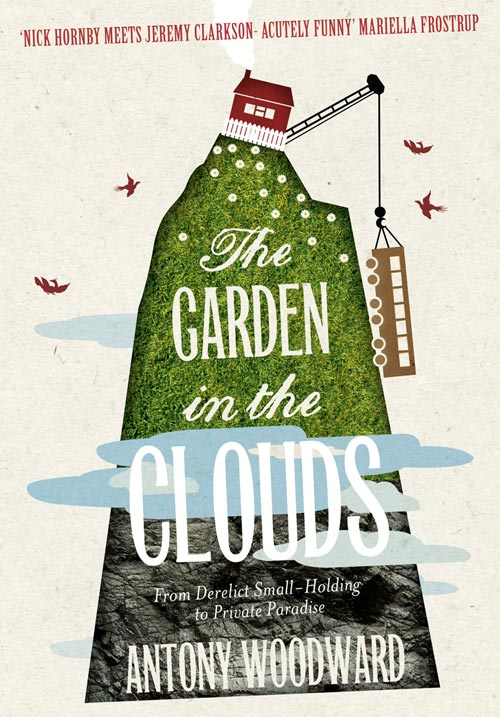

The Garden in the Clouds: From Derelict Smallholding to Mountain Paradise

THE GARDEN IN

THE CLOUDS

From Derelict Smallholding to Mountain Paradise

ANTONY WOODWARD

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperPress in 2010

Copyright © Antony Woodward 2010

Antony Woodward asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Source ISBN: 9780007216512

Ebook Edition © MAY 2010 ISBN: 9780007351930

Version: 2016-02-19

To Vez

sine qua non

It is better to have your head in the clouds, and know where you are…than to breathe the clearer atmosphere below them, and think that you are in paradise.

HENRY DAVID THOREAU

The link between imagination and place is no trivial matter.

The existential question, ‘Where do I belong?’ is addressed to the imagination. To inhabit a place physically, but to remain unaware of what it means or how it feels, is a deprivation more profound than deafness at a concert or blindness in an art gallery. Humans in this condition belong no where.

EUGENE WALTER, Placeways, 1988

Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

Copyright

To Vez

Prologue

1 Walking country

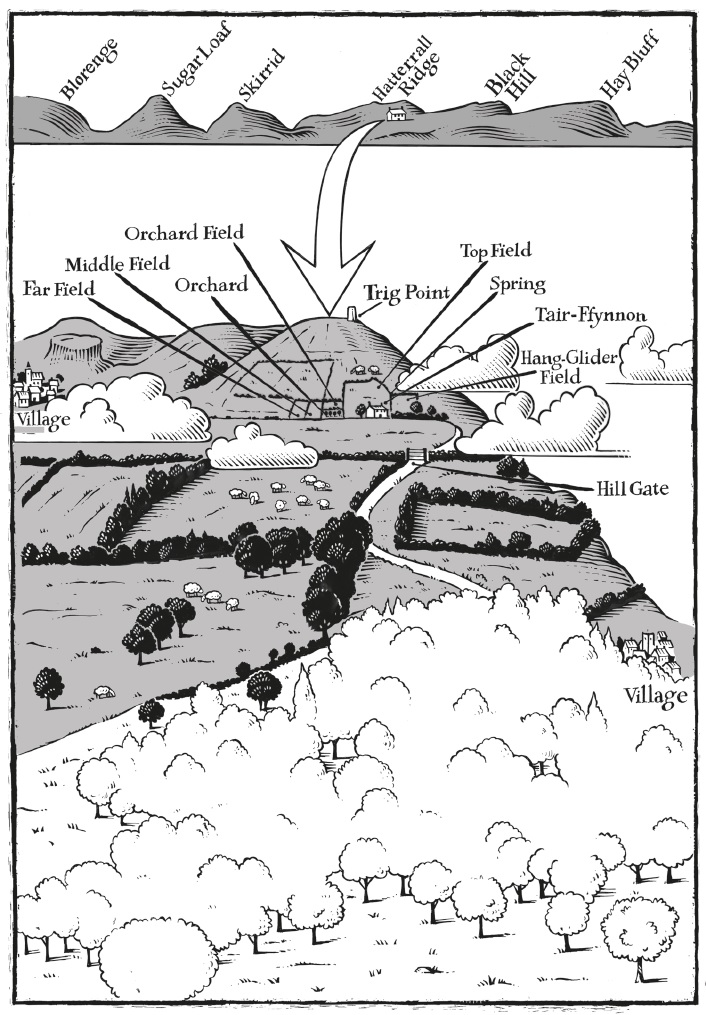

2 Tair-Ffynnon

3 The Yellow Book

4 A short detour about wood-chopping

5 Winter on the hill

6 The Not Garden

7 The perfect country room

8 The County Organiser

9 The important matter of gates

10 The orchard

11 Bees

12 How not to mow a meadow

13 The Accident

14 The pond

15 Stoning

16 Return of the County Organiser

17 Life, death and hedge-cutting

18 The house

19 ‘Garden Open Today’

Epilogue

Keep Reading

Acknowledgements

The National Gardens Scheme

About the Author

About the Publisher

Prologue

Hell is all right. The human mind is inspired enough when it comes to inventing horrors; it is when it tries to invent a Heaven that it shows itself cloddish.

EVELYN WAUGH, Put Out More Flags, 1942

My first involvement with gardening was aged seven. I am sitting in the back of my mother’s car (Austin 1300 Countryman, cream, wood-effect trim). She’s at the wheel; my father’s in the passenger seat, my older brother Jonathan is in the back with me. We’ve pulled off a country road alongside some iron railings. Through the railings a garden can be seen leading back, via a wide lawn, to a handsome stone-built villa. Wiltshire probably; possibly Gloucestershire or Somerset.

‘Antony’—my mother only used my full Christian name when she was serious—‘I won’t ask you again. Get out of the car.’

‘No.’

‘Get—out—of—the—car.’

‘Why? Why me?’

‘The more you sit here arguing, the longer we’re going to be.’

‘Why can’t Jonny do it?’

‘You’re smaller than he is. Anyway, it’s your turn.’

‘What if someone comes? What if the people come back?’

‘They won’t come back.’

‘But what if they do?’

‘I must say, I’m not sure this is wise,’ says my father. ‘It’s breaking the law.’

‘Don’t be so feeble, Peter. How could anyone mind? If the child got on with it, we could all be on our way home by now.’

‘Exactly. It’s breaking the—’

‘Be quiet, Antony.’

‘What if someone does come?’ says my father.

‘He just runs for it, of course.’ She turns to me. ‘You can come back through the gate if you want. Look,’ she adopts a more conciliatory tone, ‘it won’t take a second. You’ll be back here before you know it, and I’ll cook sausages for tea.’

‘The fence is too high. I’ll never get over.’

‘It does look high, Liza. I really do think—’ says my father.

‘Fiddlesticks. Really Peter, you’re as bad as the children.’

‘It’s not fair…where’s the bloody thing again?’

‘Don’t use bad language. It’s the helianthemum. Over there under the wall, with the small white flowers. In that raised bed. On the left.’

From the car there is a view through the wrought-iron gate, down a short, flag-stoned path onto the lawn. Diagonally across this is the raised bed, about eighty yards away.

‘The white thing by the big red bush?’

‘Yes. Now get a move on. And remember: pull downwards so a piece of the stalk comes with it.’

It had recently rained and as I push through the shrubbery to the railings, every move brings a shower of water droplets down my neck and arms. Insects hum loudly, and beetles keep dropping onto me. Straddling the crossbar, trying to get my second leg over, one of my belt loops catches on an iron point. For a few seconds I’m helpless, exposed to both the house and anyone passing. Vigorous arm movements from the car indicate that my mother thinks I’m stalling. I wriggle free, drop back down into the laurels, crawling under their cover until I reach the lawn’s edge. Then I sprint. By the raised bed, I grab at the plant, and a few moments later, breathless with adrenaline, I’m back at the gate. The latch is tight, lifting with a clang, the hinges screech deafeningly, but at last I’m back in the safety of the car.

‘Quick, go,’ I pant, pulling the car door shut.

‘Let me see,’ demands my mother.

I thrust the sprig of foliage into her hand.

‘Come on. Go.’

‘This isn’t a helianthemum,’ says my mother. ‘This is aubrietia. You nincompoop, Ant. You’ve got the wrong plant.’

‘What?’

‘This is no use at all.’

‘Well, I can’t help it. You should have said.’

‘No use at all,’ repeats my mother. ‘Why on earth would I ask for aubrietia? Quick—back you go.’

‘WHAT?’

‘Come on. We haven’t got all day.’

‘I’m not going back in there.’

‘Of course you are. And this time, use your nous,’ she adds, tapping her temple with her forefinger; ‘it’s an alpine. Come on. Get on with it.’

For the second time, I find myself ejected. ‘Well make sure you switch the engine on…’

‘Yes, yes, yes.’

The angry yell of a man’s voice comes from the direction of the house just as my hand stretches out to the raised bed: ‘Hey! You! What are you doing?’

I don’t look, I just leg it across the lawn to the flagged path to the gate. This is my undoing. Following the rain, as soon as my feet touch the flags, I perform a graceless cartwheel, coming down agonisingly on my left thigh. Picking myself up, I fumble for the gate latch. A clang, a squeal of hinges, and I’m back in the car. ‘Quick. Quick. Someone’s coming. Quick. Go. Go, go, go.’

My mother hasn’t started the engine. I dive behind the front seats as she fiddles unhurriedly with the ignition. As we at last pull away, I emerge to find my mother holding the cutting at arm’s length (she’s longsighted), appraising as she steers with one hand.

‘Please keep your eyes on the road, Liza,’ says my father.

‘That should take alright,’ she says. She starts to wrap the cutting in one of the numerous crumpled paper handkerchiefs that always surround her, the car swerving dangerously as she does so. ‘See darling?’ she says, turning to me. ‘That couldn’t have been easier, could it? All that fuss. You do make such a meal of everything.’

This book is partly about an attempt to make a garden and partly an attempt to resolve my vexed relationship with the whole subject of gardening. The specific impulse was planted about twenty years ago, during a conversation with a friend whose party trick was hypnotising people. ‘We all have a garden in our heads,’ he happened to mention. Asked to close our eyes and imagine ourselves in our favourite garden, most people will find a special place, usually a childhood garden. Real or imaginary, once chosen, it’ll always be the same place we visit, if requested to do so thereafter, again and again. This fact, he said, was indispensable to hypnotists, who need to make their subject feel secure, contented, fulfilled, calm and relaxed—in short, highly susceptible to whatever humiliating routines he had planned for them—in a hurry. ‘Just get them into the garden,’ he finished cheerfully. ‘Then you’ve got ’em.’

‘What if they don’t have a favourite garden?’

‘Everyone has a favourite garden.’

Somehow, this idea stuck in my head. The genius of it was its individuality. The instant he said it, I knew I had just such a place. It was the house where my grandmother lived when I was little: a gabled, Elizabethan Cotswold farmhouse with outbuildings, down a long drive, above a valley of hanging beech woods. The house was built of that honey-coloured limestone that seems to absorb the sunshine then radiate it back so even on grey days it still felt warm. The roof was of mossy stone tiles, the windows mullioned. The south-facing garden side was framed by two trees: a vast and ancient Irish yew and a flowering cherry whose white blossom indicated spring had arrived. A stream ran across the lawn in front of the house, feeding a natural swimming pool hewn out of the rock. Inside the dark interior, there were beams and oak panelling and a smell of wood smoke and beeswax. A trap door under the sitting-room carpet led to the cellar. Even the name was charmed: Rookwoods-on-the-Holy-Brook.

Rookwoods was sold in 1968, when I was five and my brother Jonny was seven. ‘It was far too remote for an old woman in winter,’ my mother would declare matter-of-factly when, later, we demanded to know why. ‘It only took a frost for her to be cut off.’ It was the only criticism of Rookwoods I ever heard. The sense of loss, the mounting resentment, the indignant accusations, they followed gradually. As we grew up, vignettes of our Cotswold idyll would drift back, until, by our teens, mere mention of the name was enough to trigger outraged nostalgia. My brother and I would compete for whose imagination had the greater claim on the place, trumping each other’s memories in an area in which my brother, with a two-and-a-half-year head start, had an irksome advantage.

When Granny died, decades later, we inherited two Rookwoods heirlooms. One was a bird table made by Cyril, the gardener. Architecturally, it was little different to most bird tables—a platform on a post beneath a pitched roof—but it was clearly handmade. The pitched roof was of beaten tin. Whittled oak pegs served as perches. The supporting pole had an irregular section where Cyril had taken the corners off with a draw knife. Erected in its new home, our garden, the bits gradually fell off: first the roof, then the supporting pillars, then the perches and the lip to stop the food blowing off. But, because it was oak, the rest, the pole and the platform, lasted: a daily presence outside the kitchen, gently reminding us of its charmed provenance.

The other heirloom was a picture. Before selling Rookwoods, Granny commissioned a painting of the house from a retired artist who lived nearby. The artist was Ernest Dinkel (the illustrator behind some of the classic 1930s underground posters) and he made a particularly good job of it. His watercolour, in its limed oak frame, moved with Granny to her next house. When she died it came to us, and when Jonny and I left home, it went to him, sparking a row so immense my father had a copy made for me.

I once read that in loving relationships between adults, the relationship does not start the day two people meet, but in the childhood of each partner. That’s when the template which governs adult behaviour, when it comes to love, is laid down. If that’s the case, then why shouldn’t much the same apply to our relationship with places? It’s always fascinated me that if you ask someone where, if they could have one, their secret rural hideaway would be—by a stream, say, in the woods, by the sea or in the hills—they always seem to know immediately. How can this be?

When I started trying to make my own garden, I discovered the task had actually begun years earlier, before I’d even found the place where my garden was to be, and that I was embarking on a more involved adventure than I could possibly have guessed, one in which all kinds of unexpected influences came to bear. Careful, patient assessment of the garden in my head, no doubt, might have explained some of these things, while simultaneously revealing much about myself (to make your paradise, after all, you need to know yourself). I did no such thing. Instead, I blundered on, baffled but trying to stay loyal to my instincts, following inexplicable imperatives. Only gradually did some explanations begin to dawn. The result is a book that often strays beyond the garden gate to all kinds of peripheral things, from childhood and family to wood-chopping.

My hope is that, on the off chance that others, too, have a garden in their heads alongside the one that they’re trying to make for real, my explorations will prompt them to reflect on theirs. After all, no one can deny the sheer grandeur of ambition or romantic purity of the impulse behind Britain’s greatest shared passion, to which anyone who’s ever dropped into a garden centre of a Saturday morning, hauled resentfully on a mower pull-start, or opened a packet of seeds has, however unconsciously, already succumbed.

A. W.

Tair-Ffynnon, 2010

1 Walking country

Now and then we passed through winding valleys speckled with farms that looked romantic and pretty from a distance, but bleak and comfortless up close. Mostly they were smallholdings with lots of rusted tin everywhere—tin sheds, tin hen huts, tin fences—looking rickety and weatherbattered. We were entering one of those weird zones, always a sign of remoteness from the known world, where nothing is ever thrown away. Every farmyard was cluttered with piles of cast-offs, as if the owner thought that one day he might need 132 half-rotted fence-posts, a ton of broken bricks and the shell of a 1964 Ford Zodiac.

BILL BRYSON, Notes from a Small Island, 1996

‘What d’you want that old place for? You a farmer? You don’t sound like a farmer.’

Mr. Games had the easy telephone manner of someone used to talking for a living and the cheery directness which I was beginning to associate with the Borderland brogue. It was late September and I’d been told there was nothing he didn’t know about property in the Black Mountains of South Wales. If we needed someone to bid on our behalf, then, as a pillar of one of the old established local auctioneers, valuers and land agents, no one was better for the task than Mr. Games.

‘I’m a writer.’

‘Are you, bloody hell?’

‘I was wondering, is there any chance—’

‘If you’re a writer, you’ll know Oliver Goldsmith? I was thinking of him just now.’

‘Oliver Goldsmith? No, I don’t think—’

‘Her modest looks the cottage might adorn,/Sweet as the primrose peeps beneath the thorn;/Now lost to all; her friends, her virtue fled,/Near her betrayer’s door she lays her head,/And, pinched with cold and shrinking from the shower,/With heavy heart deplores that luckless hour.’

‘That is lovely. No, I don’t know that poem, but—’

‘The Deserted Village. You must know that.’

‘I must look it up. But I was wondering—?’

‘What about Keats? Adieu! adieu! thy plaintive anthem fades/Past the near meadows, over the still stream,/Up the hill-side; and now ’tis buried deep/In the next valley-glades:/Was it a vision, or a waking dream?/Fled is that music—do I wake or sleep? How do they do it? That’s the bloody question. It’s in there you know, right from the start. Thomas, d’you read much of him? “And Death Shall Have No Dominion?”’

‘I…er…’

‘No more may gulls cry at their ears/Or waves break loud on the seashores…’

Was everyone in Border Country like this, I wondered? Everyone we met seemed to love to talk.

‘…He was nineteen. Nineteen. How can you know that stuff aged nineteen?’

‘Amazing, isn’t it? But I was wondering—’

‘So why d’you want this house anyway? It’s in the middle of bloody nowhere.’

‘That’s the point. I like—’

‘D’you read Johnston? You must’ve read him? That time at the Giant’s Causeway…’

And he was off again. Forty minutes later, with difficulty, I extricated myself (‘Got to go, have you?’)—though, as I put the phone down, I felt at least we now had a sound ally. I arranged to meet at his office the following Friday at twelve o’clock to run through the formalities before the afternoon’s auction.

The call was the culmination of a decade of dreaming followed by a three-year wild-goose chase. I’d been looking for a rural hideaway for as long as I could remember. In my mind, I knew precisely what I was after. It would be a remote, whitewashed stone cottage with a sagging roof of mossy stone slates, up a long, rocky track. Inside would be a sitting room lined with books, and battered old leather armchairs, a threadbare carpet and a blazing log fire. The place would have elements of Gavin Maxwell’s Camusfearna (his cottage on the West Coast of Scotland in Ring of Bright Water), Uncle Monty’s Lake District retreat in the film Withnail and I, and Shackleton’s hut at the South Pole, with its tin stove pipe, cosy bunks and (yes, let us not forget) plentiful wooden packing cases of canned lobster soup and vintage claret. It had to be somewhere properly wild: mountains or moorland—walking country—where the wind howled and the rain lashed, somewhere that would be cut off for weeks by snow in winter, as an antidote to the airless, Tupperware skies of London. In this place, after long walks in the hills (wearing sturdy, red-laced boots), worries could be soaked away in deep baths while sipping whisky (not that I liked whisky) while savouring the sound of the weather hammering the windows. It seemed a straightforward enough fantasy, yet finding it had proved anything but. Scotland, Snowdonia and the Lakes were too far. The Dales and High Peak were too expensive. Exmoor wasn’t wild enough. Dartmoor wasn’t mountainous enough.

And thus my late twenties passed into my thirties, with me no nearer, mentally or financially, to finding my rural hideaway. So, my forties on the horizon, I compromised. I bought an ancient Land Rover and parked it in the street as a daily reminder that one day that’s where I was going.

Then I met Vez, who also worked in London, and thoughts of escape to remote rural hideaways seemed less urgent.

Until, out of the blue, my friend Mary called. She’d heard of a place in the Black Mountains, likely to be cheap, but we’d have to move fast. I’d not even heard of the Black Mountains, but spring was in the air and it felt like an adventure. So Vez and I dropped everything, called in sick to our respective offices, and next day drove down the M4 to Wales.

We met our mystery guide, Ian, in a pub. From the start a sense of intrigue and skulduggery pervaded the day, enough to make us feel, for once, we were on the inside track. In the pub, Ian spoke in whispers: ‘Keep your voice down, these walls have ears.’ Then he whisked us off in his car along a wide green valley of big fields, before turning up an unsigned lane, the sides of which narrowed and deepened as it began to climb until the car fitted it like a tube train. Up and up we went, the lane kinking and twisting past ancient tree trunks whose vast boles were sawn flush to allow just enough room for a car to squeeze by. Eventually the gradient eased and we emerged, blinking in the light, at a small crossroads. Ahead of us, framed through a gateway, rose a table-topped summit. ‘Sugar Loaf,’ said Ian.

He took a turning marked ‘NO THROUGH ROAD’. A dark mountainscape opened up on our left, completely different to the grassy valley where we’d started. A hairpin bend took us steeply uphill again. The hedges were getting scrappier now, and gateways revealed ever-more-dramatic panoramas of heathery hilltops above sheep-dotted fields. Up and up—my ears popped—until a quarter of a mile later the road ended at a gate between dry-stone walls. An embossed wooden sign read: ‘NO CARS ON THE COMMON. PRIVATE ACCESS ONLY.’ Beyond the gate a rocky track bordered by a stone wall continued upwards, curving tantalisingly out of sight between bracken-covered banks before disappearing into wispy fog. ‘That’s as far as we can go,’ said Ian at that point. There were complications. The house was being sold by Court Order: a bitter divorce. There was no question of actually seeing the place. We wouldn’t understand the niceties, he said, but he’d keep us posted.

And with that, we returned to London. But over the days and weeks that followed, phrases Ian had used kept drifting back. ‘Over a thousand feet’, ‘National Park’, ‘Offa’s Dyke’, ‘red kites’, ‘wild ponies’, ‘spring water’…Each alone was enough to send me into happy reveries. As it turned out, however, it didn’t come to market. ‘Don’t give up,’ said Ian. ‘It’ll happen.’

Our next attempt to see the place coincided with the height of the foot-and-mouth epidemic in 2001. With the grand obliviousness to rural affairs that only the truly urban can display, we’d booked a B&B, packed walking boots and maps and arrived in the Black Mountains astonished to find every road into the uplands ending in sinister roadblocks plastered with yellow warning notices: ‘FOOT-AND-MOUTH DISEASE. BY ORDER, KEEP OUT.’