Полная версия

The Garden in the Clouds: From Derelict Smallholding to Mountain Paradise

There was, of course, one other small matter. Would anything grow so high up? But here again, I was inclined to optimism. We already had evidence that potatoes, mangelwurzels and hay had been grown on Tair-Ffynnon’s rocky policies, as that’s what many of its previous inhabitants had lived on. If they could survive, no doubt other things could too. Derek Jarman had coaxed life out of shingle, by the sea, with all that that implied in terms of wind and salt.* Stuff must grow on mountains, too; it was just a matter of finding out what. In fact, in the circumstances, my course of action was obvious: ask Uncle William.

Uncle William was the great gardener of the family, and my mother’s half-brother. He and my Aunt Jeanette lived in a secluded nook of the Dorset Downs not far from Sherborne. Ranged around a seventeenth-century chalk and flint cottage (its thatched roof pulled well down over its eyebrows, at home in any book of idyllic English country cottages) was a garden that even I couldn’t fail to notice was a plantsman’s delight. The last time I was there, one August, summer was in its dusty and desiccated last gasp. Yet in Uncle William’s garden greenery, foliage and flowers were positively clawing their way out of the ground. Apart from a lawn behind the house, there was hardly a square inch of space that wasn’t bursting with trees, shrubs, climbers, pergolas and pots. In his extensive fruit and vegetable garden, the runner beans, raspberry canes and gooseberry bushes were so bowed down with the weight of provender they gave the impression that, however fast anything was picked, there was not the slightest chance of keeping pace with the output. The place had what I would learn was a hallmark of a plantsman at work: narrow paths rendered almost impassable due to the rainforest density of vegetation spilling from either side. Should you dare level a criticism at Uncle William’s garden, it was that you couldn’t see the garden for the plants.

If green fingers existed, Uncle William’s were of the most livid, fluorescent, Martian hue, and chlorophyll coursed through his veins. It was known far and wide that he had only to be handed a plant for it to perk up. Gardening rows between my parents concerning any matter of practical plant husbandry—where a particular plant was best placed, why it wasn’t doing well, what the best treatment should be—invariably ended with a defiant, pursed-lipped: ‘Well. We’ll ask William.’

As a child, I’d found Uncle William slightly intimidating.* He was a naval captain and had a deep, husky voice that exuded peremptory command. I always imagined the huskiness had come from roaring orders across the wind and spray-swept flight deck of HMS Ark Royal, of which he’d been second-in-command in the 1970s, not that I’d ever heard him raise his voice or even seen him in his naval role (though he was wearing his uniform, holding an umbrella over them, in my parents’ wedding photographs). It was a voice that implied that, once a task was stated, it might be regarded as done. I couldn’t imagine any member of the plant kingdom defying it. He was a pillar of the local establishment and churchwarden in his local parish. I was sure he must open his garden to the public, and, on a hunch, looked him up in the Yellow Book. Sure enough, there was his garden: ‘Planted over many yrs to provide pleasure from month to month the whole yr through.’

If anyone knew what would grow on a windswept hill-side 1,300 feet up, it was Uncle William. I hadn’t spoken to him for years and was summoning the courage to make the call when, out of the blue, he called us. He gathered we’d bought an unlikely property in the hills and had ideas about making a garden. (Clearly, word had spread of our offbeat acquisition, though I did wonder how my father had described Tair-Ffynnon to trigger quite such prompt interest.) As it happened, he said, he and Aunty Jeanette were visiting a garden near Usk in a few weeks time as part of the local gardens society (I later asked him about his role in this: ‘Chairman, for my sins’), and he suggested coming on to see us.

Which was how, one Saturday a few weeks later, Uncle William came to be pottering about Tair-Ffynnon’s rocky and bracken-invaded acres. He seemed amused by the whole enterprise, as he poked cheerfully about with a stick. ‘Well, your soil’s alright,’ he said, jabbing at the thick clump of nettles growing round the wood pile. ‘Nettles only grow in rich soil.’ The hundreds of molehills he thought were a good sign, too. ‘Excellent potting soil if you collect it up. If you put bottles in the vegetable garden the sound of the wind in the glass discourages them.’ We took him up to the gully where the spring ran. More jabs with the stick. ‘You can increase the sound of the running water by adding stones,’ he said. I’d briefed him about my Yellow Book plan as we progressed around the place, hovering behind him hopefully, biro and notebook at the ready for any suggestions about what we should plant. However, little apart from these general comments had so far emerged. Looking up and down the gully now, his gaze alighted on the stands of foxgloves. ‘Foxgloves,’ he said. ‘There you are. You can grow foxgloves.’

‘But foxgloves…foxgloves grow everywhere.’

Uncle William shrugged his shoulders. ‘You can only grow what will grow. You need to look around you and see what’s growing naturally.’ He looked around again, taking in the clumps of gorse, the encroaching bracken. ‘For instance,’ he said, ‘you could have a very fine bracken garden.’ He dissolved into chuckles. ‘The first bracken garden in Britain.’

I wasn’t convinced Uncle William was taking me as a gardener, or the project, seriously. After lunch, however, he opened the back of his car and revealed a boot crammed with treasures. He’d brought with him dozens of trees: crab-apples and holm oaks, birches and sessile oaks and limes. Best of all, there was a yew, and yews, we knew, grew on the hillside, because many cottages had one (often calling themselves, imaginatively, ‘Yew Tree Cottage’ or ‘Ty’r-ywen’: ‘the house by the yew’). ‘The yew,’ began Uncle William. ‘D’you remember the yew at Rookwoods? Perhaps you were too young?’

‘I remember it.’

‘Well, this is its grandchild. When Granny left, I took a cutting and planted it in the garden. This is from a cutting from my tree.’

The idea of having a genuine piece of Rookwoods, of the garden in my head, growing in my own real garden…well, I need hardly say, the thought gave me goose bumps.

A week or two later, Uncle William emailed me. His advice boiled down to:

1 Get the place fenced. You can’t do anything until that’s done.

2 Look at what grows naturally around you.

3 Visit other Yellow Book gardens at a similar height and aspect.

4 Go to the Botanic Gardens of Wales, Edinburgh and the Lake District.

5 Consult your mother’s books. She was a botanist, after all. Her shelves must be full of useful information.

As for getting into the Yellow Book, he said he could only speak from experience in Dorset, but he suspected they were ‘far too stuffy’ to take on such an unusual place. Which I presumed was his polite way of saying, ‘Forget it.’

4 A short detour about wood-chopping

The Home Handyman’s advice on smoking chimneys…did have one unusual suggestion to make: ‘Perhaps you have troublesome wind currents in your location. Find out if your neighbours have trouble, and if so, how they tackle the problem.’ What a good idea! We went at once to see what information we could gain. Our neighbours were sympathetic. Yes—they too had troublesome parlour flues. How did they get over the problem? Easy. They never used the parlour.

ELIZABETH WEST, Hovel in the Hills, 1977

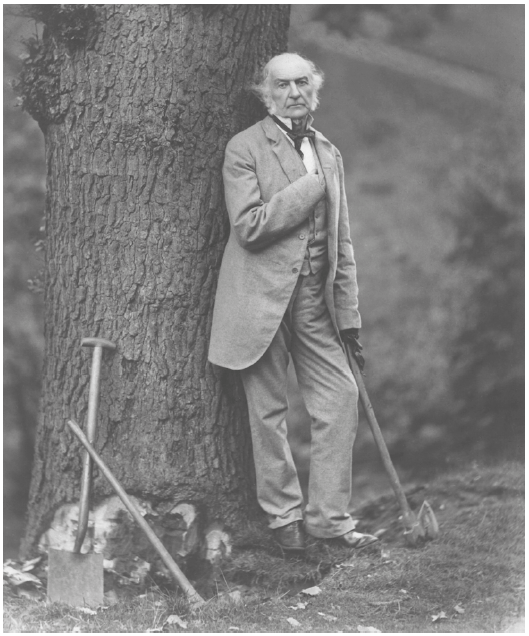

Had you gone down to the woods—technically, the arboretum—of Hawarden Castle, six miles west of Chester, in Flintshire, North Wales, on any number of afternoons during the second half of the nineteenth century, you might have encountered a diverting sight: Her Majesty, Queen Victoria’s sometime Chancellor of the Exchequer, latterly Prime Minister of England, complete with fine set of greying mutton-chop whiskers, in shabby tweeds, ‘without a coat—without a waistcoat—with braces thrown back from off the shoulders and hanging down behind’, setting to work with an axe. William Ewart Gladstone, aka ‘The Grand Old Man’, aka Liberal statesman, four-times Prime Minister, and bête noire of Benjamin Disraeli, the same man whom Churchill called his role model and whom Queen Victoria accused of always addressing her as if she were a public meeting, had an eccentric hobby. He was simply potty about wood-chopping, in particular, chopping down trees.

‘No exercise is taken in the morning, save the daily walk to morning service,’ recorded Gladstone’s son, William, in the Hawarden Visitors’ Handbook. ‘But between 3 and 4 in the afternoon he sallies forth, axe on shoulder…The scene of action reached, there is no pottering; the work begins at once, and is carried on with unflagging energy. Blow follows blow.’ He seems to have possessed more enthusiasm than aptitude for his hobby. One Christmas he almost blinded himself when a splinter flew into his eye. On another occasion he almost killed his son Harry, when a tree Gladstone was cutting fell with the boy in it.

His tree-felling was achieved only by four or five hours of unremitting exertion, and much is made in descriptions of the terrific energies he expended, the way the perspiration poured from his face and through the back of his shirt; something that, according to his supporters (and, they claimed, the vox populi), emphasised his vital, heroic nature. His opponents did not agree. ‘The forest laments,’ remarked Lord Randolph Churchill, Conservative politician and later Chancellor of the Exchequer, ‘in order that Mr. Gladstone may perspire.’ Wood-cutting even turned political when Disraeli spotted an opportunity to undermine his old foe. ‘To see Lovett, my head-woodman, fell a tree is a work of art,’ he declared smoothly in 1860. ‘No bustle, no exertion, apparently not the slightest exercise of strength. He tickles it with the axe; and then it falls exactly where he desires it.’

Gladstone took up his tree-chopping in 1852, aged forty-two, and continued with inextinguishable ardour until he was eighty-five, after which, he noted meticulously in his diary, he contented himself with mere ‘axe-work’ rather than ‘tree-felling’.

I mention Gladstone merely because, although he’s possibly the most celebrated British example, in my experience most men find at least the idea of chopping wood appealing. In America the axe is an emblem of Abraham Lincoln, George Washington and Henry David Thoreau. It’s the great symbol of the settler, the outback, of rural survival, self-reliance and the frontier spirit. Seven Presidents of the United States were born in log cabins.* Possibly this explains the axe’s curious romance. All I knew was that if my idealised rural existence had to be summed up in a single image, that image would be me either snoozing by the fire, or splitting logs on a frosty morning. Either way, the two elements were indispensable: a fire and logs to go on it.

Now, obviously lots of people like open fires. It’s tempting to say everyone, were not my reason for bringing up the subject that the two most influential figures in my life emphatically didn’t. My childhood was fireless. In the Woodward household, fires were one of the few subjects about which my parents were in complete agreement. They put their case peremptorily. Open fires were a chore. They had to be made, fed, poked and raked out. They were dirty. Their smoke ruined books. They were inefficient: everyone knew the heat went straight up the chimney, sucking draughts in its wake. They were dangerous, in a timber-framed, timber-clad house. None of these was the real reason for their antipathy, of course, which was that fires were yesterday’s way.

To understand their viewpoint, it’s necessary to remember the era. This was the 1960s and ’70s: the nuclear age, the space race, motorways, comprehensive redevelopment, Concorde, and Harold Wilson’s ‘white heat of technology’. My parents were academic scientists: Da a research chemist,* Ma a botanical geneticist. Science, to my parents, was the way forwards. My mother was feeding us limitless quantities of instant food. My father was experimenting with disposable paper underwear. In our house there would be no ugly radiators or visible heat sources (at least not to start with). The future was electric: clean, silent, odourless and available at off-peak rates. Arguments (during one of my brother’s and my periodic campaigns) that fires were cosy were ignored. The cottage chimney was bricked up.

My father was ahead of his time. Our new extension, complete with electric underfloor heating, was in place just in time for the 1973 oil crisis. The price of electricity shot up faster than heat up a chimney. The next six years (when, aged 10–16, my powers of recall were sharpest and my temperament most vindictive) saw strike after strike, power cut after power cut, culminating in the Three Day Week and the Winter of Discontent. Now, the all-electric house, without electricity, has a chilly comfortlessness that’s all its own. With heating under the floor, there are no radiators to hug. I remember long, cold, dark evenings spent hunched round a Valor paraffin heater, as we tried to conserve our torch batteries. I left home fixated with radiators, Agas and roaring pot-bellied stoves; but most of all with dear, friendly, filthy, high-maintenance, chronically inefficient, open fires.

As it transpired, my mother, as she got older, softened in this area, getting me to draw the curtains close on miserable days, wrapping herself in blankets and hugging the electric fire. ‘Granny-bugging’, she called it. And even my father had the temerity recently to declare that he likes open fires—‘in other people’s houses’.*

So, a fire and logs to go on it. With Tair-Ffynnon the archetypal lonely mountain cottage, a near-perfect enactment of almost every literary evocation of the granny-bugging fantasy, it clearly centred around an open fire, but for one small hitch. It didn’t have one. It was patently meant to have one. There was a big stone chimney breast rising out of the sitting room. But the traditional cottage grate and bread oven were long gone, replaced by a tinny metal water heater connected by pipes to the hot water tank.

One of the first tasks with which the ‘tidy’ builders we’d engaged were charged was to remove this excrescence and ‘open up’ the fireplace. With it gone, I waited with mounting impatience for my big moment: an open fire of my own. In preparation, we’d bought an old iron fireback in a salvage yard. This, with due solemnity, was placed in the hearth. I laid a fire, spreading the kindling into a neat pyramid, and struck a match. Almost immediately the room filled with smoke. It curled thickly out under the beam so it was clear none at all was going up the chimney. We endured it as long as we could until, eyes streaming, gasping for air, we had to stagger outside. Once the fire was doused and the smoke cleared, we peered up the chimney. We could see nothing. It was plainly blocked.

The following afternoon Frank the Sweep appeared with brushes and vacuum cleaners. The chimney was swept. No, he said, it wasn’t blocked, but it was a bit tarry, which could have made a difference. Anyway, it was all clear now. As his van departed, we tried again. Precisely the same happened as before. I rang round for advice. It was freely available and readily dispensed: almost certainly the wood was damp and the chimney cold. It just needed warming through: all we had to do was light a really good blaze, keep it going for at least an hour and the problem would be solved.

As it had been raining we didn’t have much in the way of dry wood, so we broke up some of the furniture that had been left behind by the previous owners. Pressing damp tea towels to our noses and mouths, we took turns to stoke the flames until they roared up the chimney so far sparks flew from the chimney pot. With such intensity of flame, it was true there was less smoke. But when we tried to light the fire the following time, it was just the same. More advice was solicited. ‘Screen the chimney breast,’ our experts said confidently. That was the standard procedure. So screen it we did. But however low we brought the screen (and we lowered it almost to the hearth itself), tendrils of smoke snaked determinedly under it into the room. ‘The opening should be more or less square,’ we were told, ‘with neither width nor height less than seventy-five per cent of the depth.’ I measured the fireplace and found this was already the case. ‘Raise the hearth: fires need air, for goodness sake.’ So we splurged £300 on a fine wrought iron grate and fire dogs to go with the fireback. And with like result. ‘Raise it further,’ we were briskly advised, as the smoke billowed forth no less prodigiously. So higher and higher we perched the iron basket, until it looked eccentric, then comic, then ludicrous and, finally, proving our advisers right, the fire no longer smoked. But that was only because it was out of sight up the chimney.

As the weeks passed our advisers’ confidence never slackened. ‘Try a hinged metal “damper” to block out cold air and rain.’ It made no difference. ‘It’ll smoke when the wind’s from the east,’ said someone else. ‘A lot of fires smoke when the wind’s from the east.’ And they were right, it did smoke when the wind was from the east. But as it came round, we were able to determine that the fire also smoked when the wind was from the west, and the south and the north. It even smoked when there was no wind at all. And on it went.*

We transferred our attentions from hearth to chimney. The chimney had been more messed about than the fireplace. The original, sturdy stone stack, when the house was enlarged, had been given mean, spindly brick extensions. But rebuilding the whole chimney was too expensive. Besides, fresh advice informed us that this was not the fundamental problem, which was almost certainly one of downdraught, caused by the position of the house relative to the rise of the hill and the prevailing wind. Just as we were about to despair, one day in the builders’ merchants a leaflet caught my eye. It advertised chimney cowls. And there, amongst the chimney cappers and birdguards, the lobster-back cowls and ‘H’ cowls, the flue outlets and ‘aspirotors’, was the very item for which we’d been searching:

In constant production for thirty years, the Aerodyne Cowl has abundantly proven its worth in curing downdraught, showing clearly that the laws of aerodynamics don’t change with the times. As wind from any direction passes through the cowl the unique venturi-shaped surfaces cause a drop in air pressure which draws smoke and fumes up the chimney for dispersal. The Aerodyne Cowl is offered with our money-back guarantee. If it fails to stop downdraught simply return it with receipt to your supplier for a full refund.

Why had no one suggested this? An ‘Aerodyne Cowl’ was duly ordered. It took three weeks to arrive, two more to be fitted, but at last we were ready once more. All I can say is it was lucky about that money-back guarantee. If anything, the fire smoked more than before.

So we gave in. We ordered a wood-burning stove. By this stage I had my doubts that even this would work, but the man in the stove shop guaranteed it. And it did. The fire roared and crackled: it just did so behind glass. And thus, at last, we had an authentic need for logs. Which is how, by the convoluted way of these things, I came by my first tractor.

Amongst the chattels that came with Tair-Ffynnon (which included two mossy Opel Kadetts, a collapsed Marina van, numerous bathtubs and an assortment of broken and rusting bedsteads, trailers, ploughs, cultivators, rollers and diesel tanks) was an iron saw-bench. A farm saw-bench is a heavy cast-iron table with, protruding through a slit in the top, a big circular blade with scarily large teeth. They date from the time when farmers cut their own planks, gateposts and firewood. Many old farms have one somewhere, superannuated, rusting away in a corner. The moment I saw ours, I wanted that saw-bench back in action. It spoke of self-sufficiency and self-reliance, of replenished wood stores and cold winter months. It was, to an almost baleful degree, a renegade of the pre-health and safety era. Like most of the older ones, ours was worked by a pulley belt, which connected the bench to a parked tractor. Modern tractors ditched pulley wheels decades ago, but a couple of the older makes, Fordsons and Fergies, still had them. All I needed to get the saw-bench into action was one of those.

The more I thought about it, the more obvious it became that an old tractor was just what Tair-Ffynnon was missing. Now the requirement for firewood spelt it out. Jonny’s remark came back to me: ‘Looks as if you’d better get yourself a tractor.’

‘Why?’ said Vez.

It was one of those typically female questions that, on the spot, it’s surprisingly difficult to answer. Arguments that a tractor was self-evidently a Good Thing to have, that it would lend tone to the place, in our straitened financial circumstances, lacked weight. ‘For towing and mowing and pulling stuff. For cutting logs…everything.’ My answer was necessarily vague, as I wasn’t absolutely sure myself of all the myriad uses to which an old tractor might be put.

‘You can buy a lot of logs for the price of a tractor,’ said Vez. ‘How much does a tractor cost?’

‘Well, you could probably get an old Fergie or a Fordson for about £1,000, but I should think…’

‘A grand! A grand! Are you out of your mind? When we haven’t even got a dry place to store anything. And Maya needs shoes.’

There’s no arguing such a case. Even I could appreciate that an inclination to see an old saw-bench back in harness, coupled with the knowledge that we could cut our own logs, sounded a little thin when ready-cut firewood was available for £40 a load.

All this I had only half worked through in my mind when I arrived on a Saturday in mid-July at the annual East Wales and Borders Vintage Auction, held, conveniently, in a field at the bottom of our hill. Over the last few days the field had been cut for silage and a tented village had sprung up so that now, although it was windless and grey, the white canvas and bunting presented a cheerful scene. Vintage auctions being the sole recreation my brother and I shared, he and my nephew Thomas had come over for the day, taking the opportunity to see us all, as had my father from Somerset. Jonny had arrived early for his usual forensic examination of the lots and announced that, amongst the collections of old railway sleepers, feed bins, mangles, chaff-cutters and nameless implements and agricultural bits and bobs, there was ‘a very nice Fergie’. And sure enough, there amongst the junkyard tractors, Lot 571, was a peach of a machine.

The finer (and indeed the broader) points of tractor mechanics meant nothing to me, but I could see this was something special. For a start, unlike the other tractors on sale, it was complete. It had four wheels, two matching mudguards, and so on. no one had attempted to spruce it up; it had a couple of dents, a buckled number plate, but still a fair amount of original grey paint. Headlamps either side of its radiator grille gave it a friendly, if slightly melancholic air. Here was one of those gems, it was clear, one might never forgive oneself for missing. Befitting its exalted status, it was one of the final lots, but the auctioneer and his throng were already working their way steadily down the rows towards it. Jonny, who knew about old Fergie prices, said not to go a penny over £1,200. By the time the brown-coated auctioneer approached, he had established himself as a waggish figure whose skilful manipulations of his bidders was drawing a larger-than-average crowd. The auctioneer hoiked his foot onto the front wheel and, as his sidekick clambered into the seat, made a whirling motion with his hand. ‘Start ’er up, Jack.’ The sidekick pressed a button and the Fergie clattered cheerfully into life with a cloud of black smoke and diesel fumes, settling down to a homely chugging rattle.