Полная версия

The Count of Monte Cristo

“Oh, dear, yes, sir; the abbé’s dungeon was forty or fifty feet distant from that of an old agent of Bonaparte’s—one of those who had the most contributed to the return of the usurper in 1815, a very resolute and very dangerous man.”

“Indeed!” said the Englishman.

“Yes,” replied M. de Boville; “I myself had occasion to see this man in 1816 or 1817, and we could only go into his dungeon with a file of soldiers: that man made a deep impression on me; I shall never forget his countenance!”

The Englishman smiled imperceptibly.

“And you say, sir,” he said, “that the two dungeons———”

“Were separated by a distance of fifty feet; but it appears that this Edmond Dantès———”

“This dangerous man’s name was———”

“Edmond Dantès. It appears, sir, that this Edmond Dantès had procured tools, or made them, for they found a passage by which the prisoners communicated.”

“This passage was formed, no doubt, with an intention of escape?”

“No doubt; but unfortunately for the prisoners, the Abbé Faria had an attack of catalepsy, and died.”

“That must have cut short the projects of escape.”

“For the dead man, yes,” replied M. de Boville, “but not for the survivor: on the contrary, this Dantès saw a means of accelerating his escape. He, no doubt, thought that prisoners who died in the Château d’If were interred in a burial-ground as usual, and he conveyed the dead man into his own cell, assumed his place in the sack in which they had sewed up the defunct, and awaited the moment of interment.”

“It was a bold step, and one that indicated some courage,” remarked the Englishman.

“As I have already told you, sir, he was a very dangerous man; and fortunately, by his own act disembarrassed the government of the fears it had on his account.”

“How was that?”

“How? do you not comprehend?”

“No.”

“The Château d’If has no cemetery, and they simply throw the dead into the sea, after having fastened a thirty-six pound bullet to their feet.”

“Well?” observed the Englishman, as if he were slow of comprehension.

“Well, they fastened a thirty-six pound bullet to his feet, and threw him into the sea.”

“Really!” exclaimed the Englishman.

“Yes, sir,” continued the inspector of prisons. “You may imagine the amazement of the fugitive when he found himself flung headlong beneath the rocks! I should like to have seen his face at that moment.”

“That would have been difficult.”

“No matter,” replied De Boville, in supreme good-humour at the certainty of recovering his two hundred thousand francs,—“no matter, I can fancy it.”

And he shouted with laughter.

“So can I,” said the Englishman, and he laughed too; but he laughed as the English do, at the end of his teeth.

“And so,” continued the Englishman, who first regained his composure, “he was drowned?”

“Unquestionably.”

“So that the governor got rid of the fierce and crazy prisoner at the same time?”

“Precisely.”

“But some official document was drawn up as to this affair, I suppose?” inquired the Englishman.

“Yes, yes, the mortuary deposition. You understand, Dantè;s’ relations, if he had any, might have some interest in knowing if he were dead or alive.”

“So that now, if there were anything to inherit from him, they may do so with easy conscience. He is dead, and no mistake about it?”

“Oh, yes; and they may have the fact attested whenever they please.”

“So be it,” said the Englishman. “But to return to these registers.”

“True, this story has diverted our attention from them. Excuse me.”

“Excuse you for what? for the story? By no means; it really seems to me very curious.”

“Yes, indeed. So, sir, you wish to see all relating to the poor abbé, who really was gentleness itself?”

“Yes, you will much oblige me.”

“Go into my study here, and I will show it to you.”

And they both entered M. de Boville’s study.

All was here arranged in perfect order; each register had its number, each file of paper its place. The inspector begged the Englishman to seat himself in an arm-chair, and placed before him the register and documents relative to the Château d’If, giving him all the time he desired to examine it, whilst De Boville seated himself in a corner, and began to read his newspaper.

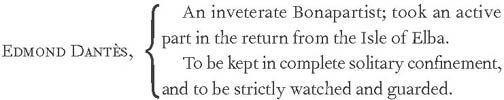

The Englishman easily found the entries relative to the Abbé Faria; but it seemed that the history which the inspector had related interested him greatly, for after having perused the first documents he turned over the leaves until he reached the deposition respecting Edmond Dantès. There he found everything arranged in due order,—the denunciation, examination, Morrel’s petition, M. de Villefort’s marginal notes. He folded up the denunciation quietly, and put it as quietly in his pocket; read the examination, and saw that the name of Noirtier was not mentioned in it; perused, too, the application, dated 10th April 1815, in which Morrel, by the deputy-procureur’s advice, exaggerated with the best intentions (for Napoleon was then on the throne) the services Dantès had rendered to the imperial cause,—services which Villefort’s certificates rendered indispensable. Then he saw through all. This petition to Napoleon, kept back by Villefort, had become, under the second restoration, a terrible weapon against him in the hands of the procureur du roi. He was no longer astonished when he searched on to find in the register this note placed in a bracket against his name:—

Beneath these lines was written, in another hand:

“See note above—nothing can be done.”

He compared the writing in the bracket with the writing of the certificate placed beneath Morrel’s petition, and discovered that the note in the bracket was the same writing as the certificate,—that is to say, were in Villefort’s handwriting.

As to the note which accompanied this, the Englishman understood that it might have been added by some inspector, who had taken a momentary interest in Dantès’ situation, but who had, from the remarks we have quoted, found it impossible to give any effect to the interest he experienced.

As we have said, the inspector, from discretion, and that he might not disturb the Abbé Faria’s pupil in his researches, had seated himself in a corner, and was reading Le Drapeau Blanc.

He did not see the Englishman fold up and place in his pocket the denunciation written by Danglars under the arbour of La Réserve, and which had the postmark of Marseilles, 2nd March, delivery 6 o’clock p.m.

But it must be said that if he had seen it, he attached so small importance to this scrap of paper, and so great importance to his 200,000 francs, that he would not have opposed what the Englishman did, how incorrect soever it might be.

“Thanks!” said the latter, closing the register with a noise, “I have all I want; now it is for me to perform my promise. Give me a simple assignment of your debt; acknowledge therein the receipt of the cash, and I will hand you over the money.”

He rose, gave his seat to M. de Boville, who took it without ceremony, quickly drew out the required assignment, whilst the Englishman was counting out the bank-notes on the other side of the desk.

29 The House of Morrel and Son

ANYONE WHO HAD quitted Marseilles a few years previously well acquainted with the interior of Morrel’s house, and had returned at this date, would have found a great change.

Instead of that air of life, of comfort, and of happiness that exhales from a flourishing and prosperous house,—instead of the merry faces seen at the windows, of the busy clerks hurrying to and fro in the long corridors—instead of the court filled with bales of goods, re-echoing the cries and the jokes of the porters, he would have at once perceived an air of sadness and gloom. In the deserted corridor and the empty office, out of all the numerous clerks that used to fill the office, but two remained. One was a young man of three or four-and-twenty who was in love with M. Morrel’s daughter, and had remained with him, spite of the efforts of his friends to induce him to withdraw; the other was an old one-eyed cashier, named Coclès, a nickname given him by the young men who used to inhabit this vast beehive, now almost deserted, and which had so completely replaced his real name that he would not, in all probability, have replied to any one who addressed himself by it.

Coclès remained in M. Morrel’s service, and a most singular change had taken place in his situation; he had at the same time risen to the rank of cashier, and sunk to the rank of a servant. He was, however, the same Coclès, good, patient, devoted, but inflexible on the subject of arithmetic, the only point on which he would have stood firm against the world, even against M. Morrel, and strong in the multiplication-table, which he had at his fingers’ ends, no matter what scheme or what trap was laid to catch him. In the midst of the distress of the house, Coclès was the only one unmoved. Coclès had seen all these numerous clerks go without thinking of inquiring the cause of their departure: everything was, as we have said, a question of arithmetic to Coclès, and during twenty years he had always seen all payments made with such exactitude, that it seemed as impossible to him that the house should stop payment, as it would to a miller that the river that so long turned his mill should cease to flow.

Nothing had as yet occurred to shake Coclès’ belief; the last months’ payment had been made with the most scrupulous exactitude; Coclès had detected an error of fourteen sous to the prejudice of Morrel, and the same evening he had brought them to M. Morrel, who, with a melancholy smile, threw them into an almost empty drawer, saying:

“Thanks, Coclès, you are the pearl of cashiers.”

Coclès retired perfectly happy, for this eulogium of M. Morrel, himself the pearl of the honest men of Marseilles, flattered him more than a present of fifty pounds. But since the end of the month, M. Morrel had passed many an anxious hour. In order to meet the end of the month, he had collected all his resources, and, fearing lest the report of his distress should get bruited abroad at Marseilles when he was known to be reduced to such an extremity, he went to the fair of Beaucaire to sell his wife and daughter’s jewels, and a portion of his plate. By this means the end of the month was passed, but his resources were now exhausted. Credit, owing to the reports afloat, was no longer to be had; and to meet the £4000 due on the 15th of the present month to M. de Boville, and the £4000 due on the 15th of the next month, M. Morrel had in reality, no hope but the return of the Pharaon, whose departure he had learnt from a vessel which had weighed anchor at the same time, and which had already arrived in harbour.

But this vessel which, like the Pharaon, came from Calcutta had arrived a fortnight, whilst no intelligence had been received of the Pharaon.

Such was the state of things when, the day after his interview with M. de Boville, the confidential clerk of the house of Thomson and French, of Rome, presented himself at M. Morrel’s. Emmanuel received him. Every fresh face alarmed the young man, for every fresh face meant a fresh creditor coming, in his uncertainty, to consult the head of the firm. The young man, wishing to spare his employer the pain of this interview, questioned the new-comer; but the stranger declared he had nothing to say to M. Emmanuel, and that his business was with M. Morrel in person.

Emmanuel sighed, and summoned Coclès. Coclès appeared, and the young man bade him conduct the stranger to M. Morrel’s apartment. Coclès went first, and the stranger followed him. On the staircase they met a beautiful girl of sixteen or seventeen, who looked with anxiety at the stranger.

“M. Morrel is in his room, is he not, mademoiselle Julie?” said the cashier.

“Yes; I think so, at least,” said the young girl hesitatingly. “Go and see, Coclès, and, if my father is there, announce this gentleman.”

“It will be useless to announce me, mademoiselle,” returned the Englishman. “M. Morrel does not know my name; this worthy gentleman has only to announce the confidential clerk of the house of Thomson and French, of Rome, with whom your father does business.”

The young girl turned pale, and continued to descend, whilst the stranger and Coclès continued to mount the staircase. She entered the office where Emmanuel was, whilst Coclès, by the aid of a key he possessed, opened a door in the corner of a landing-place on the second staircase, conducted the stranger into an antechamber, opened a second door, which he closed behind him, and after having left the clerk of the house of Thomson and French alone, returned and signed to him that he could enter.

The Englishman entered, and found Morrel seated at a table, turning over the formidable columns of his ledger, which contained the list of his liabilities. At the sight of the stranger, M. Morrel closed the ledger, rose, and offered a seat to the stranger, and when he had seen him seated, resumed his own chair.

Fourteen years had changed the worthy merchant, who, in his thirty-sixth year at the opening of this history, was now in his fiftieth. His hair had turned white, time and sorrow had ploughed deep furrows on his brow, and his look, once so firm and penetrating, was now irresolute and wandering, as if he feared being forced to fix his attention on an idea or a man. The Englishman looked at him with an air of curiosity, evidently mingled with interest.

“Monsieur,” said Morrel, whose uneasiness was increased by this examination, “you wish to speak to me?”

“Yes, monsieur; you are aware from whom I come?”

“The house of Thomson and French; at least, so my cashier tells me.”

“He has told you rightly. The house of Thomson and French had 300,000 or 400,000 francs (£12 to £16,000) to pay this month in France, and, knowing your strict punctuality, have collected all the bills bearing your signature, and charged me as they became due to present them, and to employ the money otherwise.”

Morrel sighed deeply, and passed his hand over his forehead, which was covered with perspiration.

“So, then, sir,” said Morrel, “you hold bills of mine?”

“Yes, and for a considerable sum.”

“What is the amount?” asked Morrel, with a voice he strove to render firm.

“Here is,” said the Englishman, taking a quantity of papers from his pocket, “an assignment of 200,000 francs to our house by M. de Boville, the inspector of prisons, to whom they are due. You acknowledge, of course, you owe this sum to him?”

“Yes, he placed the money in my hands at four and a half per cent. nearly five years ago.”

“When are you to pay?”

“Half the 15th of this month, half the 15th of next.”

“Just so; and now here are 32,000 francs payable shortly; they are all signed by you, and assigned to our house by the holders.”

“I recognise them,” said Morrel, whose face was suffused as he thought that, for the first time in his life, he would be unable to honour his own signature. “Is this all?”

“No, I have for the end of the month these bills which have been assigned to us by the house of Pascal, and the house of Wild and Turner, of Marseilles, amounting to nearly 55,000 francs (£2200); in all, 287,500 francs (£11,500).”

It is impossible to describe what Morrel suffered during this enumeration.

“Two hundred and eighty-seven thousand five hundred francs,” repeated he.

“Yes, sir,” replied the Englishman.

“I will not,” continued he, after a moment’s silence, “conceal from you that whilst your probity and exactitude up to this moment are universally acknowledged, yet the report is current in Marseilles that you are not able to meet your engagements.”

At this almost brutal speech Morrel turned deathly pale.

“Sir,” said he, “up to this time—and it is now more than four-and-twenty years since I received the direction of this house from my father, who had himself conducted it for five-and-thirty years—never has anything bearing the signature of Morrel and Son been dishonoured.”

“I know that,” replied the Englishman. “But as a man of honour should answer another, tell me fairly, shall you pay these with the same punctuality?”

Morrel shuddered, and looked at the man, who spoke with more assurance than he had hitherto shown.

“To questions frankly put,” said he, “a straight-forward answer should be given. Yes, I shall pay, if, as I hope, my vessel arrives safely; for its arrival will again procure me the credit which the numerous accidents, of which I have been the victim, have deprived me; but if the Pharaon should be lost, and this last resource be gone———”

The poor man’s eyes filled with tears.

“Well,” said the other, “if this last resource fail you?”

“Well,” returned Morrel, “it is a cruel thing to be forced to say, but, already used to misfortune, I must habituate myself to shame. I fear I shall be forced to suspend my payments.”

“Have you no friends who could assist you?”

Morrel smiled mournfully.

“In business, sir,” said he, “one has no friends, only correspondents.”

“It is true,” murmured the Englishman; “then you have but one hope.”

“But one.”

“The last?”

“The last.”

“So that if this fail———”

“I am ruined,—completely ruined!”

“As I came here a vessel was entering the port.”

“I know it, sir: a young man, who still adheres to my fallen fortunes, passes a part of his time in a belvedere at the top of the house, in hopes of being the first to announce good news to me: he has informed me of the entrance of this ship.”

“And it is not yours?”

“No, it is a vessel of Bordeaux, La Gironde; it comes from India also; but it is not mine.”

“Perhaps it has spoken the Pharaon, and brings you some tidings of it?”

“Shall I tell you plainly one thing, sir? I dread almost as much to receive any tidings of my vessel as to remain in doubt. Incertitude is still hope.”

Then in a low voice Morrel added:

“This delay is not natural. The Pharaon left Calcutta the 5th of February; it ought to have been here a month ago.”

“What is that?” said the Englishman. “What is the meaning of this noise?”

“Oh! oh!” cried Morrel, turning pale, “what is this?”

A loud noise was heard on the stairs of people moving hastily, and half-stifled sobs. Morrel rose and advanced to the door; but his strength failed him, and he sank into a chair. The two men remained opposite one another, Morrel trembling in every limb, the stranger gazing at him with an air of profound pity. The noise had ceased; but it seemed that Morrel expected something; something had occasioned the noise, and something must follow.

The stranger fancied he heard footsteps on the stairs, and that the steps, which were of those several persons, stopped at the door. A key was inserted in the lock of the first door, and the creaking of hinges was audible.

“There are only two persons who have the key of the door,” murmured Morrel, “Coclès and Julie.”

At this instant the second door opened, and the young girl, her eyes bathed with tears, appeared.

Morrel rose tremblingly, supporting himself by the arm of the chair. He would have spoken, but his voice failed him.

“Oh, father!” said she, clasping her hands, “forgive your child for being the messenger of ill.”

Morrel again changed colour. Julie threw herself into his arms.

“Oh, father, father!” murmured she, “courage!”

“The Pharaon has then perished?” said Morrel, in a hoarse voice.

The young girl did not speak; but she made an affirmative sign with her head as she lay on her father’s breast.

“And the crew?” asked Morrel.

“Saved,” said the girl; “saved by the crew of the vessel that has just entered the harbour.”

Morrel raised his two hands to heaven with an expression of resignation and sublime gratitude.

“Thanks, my God,” said he, “at least you strike but me alone.”

Spite of his phlegm a tear moistened the eye of the Englishman.

“Come in, come in,” said Morrel, “for I presume you are all at the door.”

Scarcely had he uttered these words than Madame Morrel entered, weeping bitterly, Emmanuel followed her, and in the antechamber were visible the rough faces of seven or eight half-naked sailors.

At the sight of these men the Englishman started and advanced a step; then restrained himself, and retired into the farthest and most obscure corner of the apartment.

Madame Morrel sat down by her husband and took one of his hands in hers, Julie still lay with her head on his shoulder, Emmanuel stood in the centre of the chamber, and seemed to form the link between Morrel’s family and the sailors at the door.

“How did this happen?” said Morrel.

“Draw nearer, Penelon,” said the young man, “and relate all.”

An old seaman, bronzed by the tropical sun, advanced, twirling the remains of a hat between his hands.

“Good-day, M. Morrel,” said he, as if he had just quitted Marseilles the previous evening, and had just returned from Aix to Toulon.

“Good-day, Penelon!” returned Morrel, who could not refrain from smiling through his tears, “where is the captain?”

“The captain, M. Morrel,—he has stayed behind sick at Palma; but, please God, it won’t be much, and you will see him in a few days all alive and hearty.”

“Well, now tell your story, Penelon.”

Penelon rolled his quid in his cheek, placed his hand before his mouth, turned his head, and sent a long jet of tobacco-juice into the antechamber, advanced his foot, and began:

“You see, M. Morrel,” said he, “we were somewhere between Cape Blanc and Cape Bogador, sailing with a fair breeze south-south-west after a week’s calm, when Captain Gaumard comes up to me,—I was at the helm, I should tell you,—and says, ‘Penelon, what do you think of those clouds that are arising there?’

“I was just then looking at them myself. ‘What do I think, captain? why I think that they are rising faster than they have any business, and that they would not be so black if they did not mean mischief.’

“‘That’s my opinion too,’ said the captain, ‘and I’ll take precautions accordingly. We are carrying too much canvas. Holloa! all hands to slacken sail and lower the flying jib.’

“It was time; the squall was on us and the vessel began to heel.

“‘Ah,’ said the captain, ‘we have still too much canvas set; all hands to lower the mainsail!’ Five minutes after it was down, and we sailed under mizzen-topsails and topgallant-sails.

“‘Well, Penelon,’ said the captain, ‘what makes you shake your head?’

“‘Why,’ I says, ‘I don’t think that we shall stop here.’

“‘I think you are right,’ answered he; ‘we shall have a gale.’

“‘A gale! more than that, we shall have a tempest, or I know nothing about it.’

“You could see the wind coming like the dust at Montredon: luckily the captain understood his business.

“‘All hands take in two reefs in the topsails,’ cried the captain; ‘let go the bowlines, brace to, lower the topgallant-sails, haul out the reef-tackles on the yards.’”

“That was not enough for those latitudes,” said the Englishman:“I should have taken four reefs in the topsails, and lowered the mizzen.”

His firm, sonorous, and unexpected voice made every one start. Penelon put his hand over his eyes, and then stared at the man who thus criticised the manœuvres of his captain.

“We did better than that, sir,” said the old sailor, with a certain respect; “we put the helm to the wind to run before the tempest; ten minutes after we struck our topsails and scudded under bare poles.”

“The vessel was very old to risk that,” said the Englishman.