Полная версия

Sisters, Secrets and Sacrifice: The True Story of WWII Special Agents Eileen and Jacqueline Nearne

Jacqueline had no idea about Buckmaster’s admiration for her ‘delicate bone’; she was just delighted that she had been given a second chance. She promised herself that she would work as hard as she possibly could and prove to everyone that Lieutenant Colonel Woolrych’s comments on her finishing report had been completely wrong.

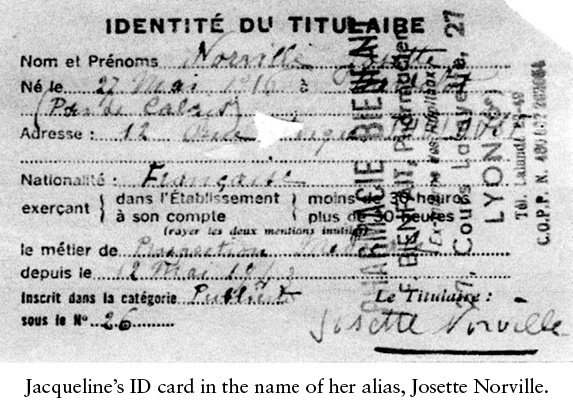

Preparations now began for her departure for France. She was given a new name, Josette Norville, and told that her cover story would be that she was a sales representative of a pharmaceutical company, Pharmacie Bienfait of Lyons,7 travelling extensively around a large area of France in the course of her work. Her cover had similarities to her own life. The new name gave her the same initials as her own and the fake occupation was virtually the same as her real employment had been, although she would be selling different commodities. She had two code names, one of which was Designer. The choice of the other was bizarre: she was to be known as Jacqueline. This was the same name as that adopted by Yvonne Rudellat, one of the first female agents to be sent to France in July 1942. (She too had received a bad training report and, at a time when political correctness would have been regarded as an alien concept, her instructor referred to her as ‘the little old lady’.8 She was 45 years old.) Jacqueline’s code name was not only already allocated to someone else but was also her real name, thus rendering it useless as a security measure. Not wanting to make a fuss, she accepted this absurdity without comment, assuming that Buckmaster knew what he was doing. Before long she was introduced to a man called Maurice, for whom she would be working in France as a courier.

Maurice Southgate (Hector) was born in Paris. It was said that his British parents had spent their honeymoon in the French capital and had liked it so much that they decided to stay, although they and their son remained British citizens. Southgate grew up in France and, like Jacqueline, spoke the language fluently without a trace of an English accent. Three years older than his new courier, he was married to a Frenchwoman, Marie Josette Lecolier – known as Josette – and, until coming to England to join the Royal Air Force, had lived in Paris, where he ran his own successful business, designing and manufacturing furniture. When he arrived in England his main desire was to become a pilot, but the Air Ministry declared him to be too old and had other ideas for his employment. Because of his language skills he, now Sergeant Southgate, was sent back to France as an interpreter for the RAF members of the British Expeditionary Force. He was still in France when, at the beginning of June 1940, Operation Dynamo ended its mission to rescue the BEF from the clutches of the Germans and Operation Ariel, a mopping-up exercise and the follow-on to Operation Dynamo, began.

Southgate, along with several thousand troops and British civilians, boarded HMT Lancastria, one of the ships at anchor in the Charpentier Roads, around 10 nautical miles from St Nazaire, on 17 June. Brought out from St Nazaire in smaller boats, the passengers were desperate to get away from the advancing German troops and back to Britain, but the master of the Lancastria, Captain Rudolph Sharp, wanted to sail across the Channel in convoy with the other ships. While they waited for these to be boarded, the Lancastria took on more and more passengers herself. Originally built to carry 2,200 people, by the time she was ready to sail on that June day she was seriously overloaded. Estimates of the actual passenger numbers varied from 4,000 to 9,000, with many being forced to travel in the ship’s holds, well below the waterline.

Just before 4 p.m. that afternoon several German bombers – Junkers 88s – appeared overhead and dropped bombs on the waiting ships. The Lancastria was hit four times and within 20 minutes she sank. Of all the thousands who had wearily climbed on board that day, there were only 2,477 survivors. Maurice Southgate was one of them. He spent hours trying to keep afloat in water that was covered with wreckage, dismembered bodies and burning fuel oil. Eventually he was rescued and, exhausted, was brought to England, landing at the Cornish port of Falmouth two days after his ordeal. He recorded what had happened to him in a diary:

I disembarked in Falmouth 19th June 1940, covered in a blanket and shoeless. I was taken by ambulance to a nearby camp, where I was able to take a shower and lose my watch. Then came a coach journey, a magnificent trip in the English countryside, to Plymouth RAF Station where I met with several of my squadron companions in the Sergeant’s mess. I was met with open arms, cries and lots of beer.

Next morning, in ill-fitting uniform, I left for London and arrived at my parents on the evening of 20th June 1940, my birthday. Both parents crying, as they had no news for several days, whilst the evacuation was taking place. I was listed missing and have had a lot of trouble establishing my credentials at the finance department of the ministry.9

The sinking of HMT Lancastria was, and remains to this day, the worst ever British maritime disaster. The total number of lives lost in the debacle was more than the combined number of deaths in both the Titanic and the Lusitania, yet the full circumstances of the tragedy were never properly reported, as Prime Minister Churchill was concerned that it was one catastrophe too many for the British public to bear and ordered a ban on the reporting of the ship’s demise. The news was eventually broken in America, with a few subsequent reports in British newspapers several weeks later.

Despite his narrow escape from death, Southgate was anxious to return to France as soon as he could. By now resigned to the fact that he would never become an RAF pilot, he was determined to do something to help defeat the Nazis, but it took him nearly two more years before he was able to join the SOE. Once he had been identified as a possible agent, however, things began to move fast. He was given an RAF commission and attended training courses, from which he emerged with glowing reports.

When he and Jacqueline Nearne were introduced to each other in the early autumn of 1942 it was the beginning of what would become a close and highly efficient working relationship. The pair had a huge task in front of them. They would be building a circuit that stretched from Châteauroux, capital of the département of Indre in central France, to Tarbes in the south-western département of Hautes-Pyrénées, only 100 kilometres away from the Spanish border. Their circuit, named Stationer, would cover almost half the entire area of France and for a time Jacqueline would be its only courier.

With their departure for France imminent, Jacqueline and Southgate were given clothes made in the French style and bearing French labels. Jacqueline had two suits, two blouses and skirts, two pairs of pyjamas and two pairs of shoes. The pyjamas were almost useless after the first wash, as the material was of a very inferior quality and they shrank badly. But since this was all that was available in France at that time, it was what the agents had to have. Jacqueline was given a few days’ leave and used the time to say goodbye to Didi.

Undaunted by the lack of a positive response to her pleas to be sent to France, Didi had continued to press for a transfer. Still unaware of the pact her sister had made with Maurice Buckmaster and Vera Atkins, when she met Jacqueline she cheerfully relayed the details of her latest application to Jacqueline and, in turn, received the news that her sister was leaving her. Although she had known that their parting would eventually come, it still gave her a jolt to know that Jacqueline would soon be gone. The girls had been together for all Didi’s life and now they would be in different countries, but they would always be close to each other in spirit and both looked forward to the time when they would be together again; Didi hoped it would be in France while Jacqueline fervently prayed that it would be in England. She was still frightened for her sister but had done everything she could to ensure she remained at her listening station in relative safety for the rest of the war.

Back at SOE headquarters Jacqueline was told that she and Maurice Southgate would be leaving at the end of October, and was instructed to be ready. Two days before departure Buckmaster came to see them both and gave Jacqueline a necklace and a watch, as well as 100,000 French francs. It was his habit to give female agents some item of jewellery, not only as a parting gift but, believing that they might be able to sell it, as a source of money should they find themselves without funds. Jacqueline was touched by this thoughtfulness and felt that Buckmaster was someone she could trust, declaring him to be ‘sympathetic and very capable’.10

She and Southgate were taken to the aerodrome in Bedfordshire from where they would be leaving and, on the appointed day, boarded a Royal Air Force Halifax and took off for France. Arriving over the dropping zone, the pilot saw no lights from the reception committee and so the pair were returned to England. Eight days later there was a new moon and another flight was organized, but as the plane approached the dropping zone a thick fog swirled up and covered all sight of the ground. Again they were forced to return to England. It is likely that they returned home after this abortive trip, as the next attempt to reach France, their third, was not made until 30 December, with the same result. Jacqueline was beginning to believe that she would never get to France. This belief became more entrenched when, on the fourth attempt, the aircraft developed a technical problem before it had even left the runway and the flight was cancelled.

Eventually on the evening of 25 January, three months after their first attempt, Jacqueline and Southgate boarded another Halifax of 161 Squadron and were flown by Flight Lieutenant Prior to a dropping zone near the small town of Brioude in the Haute-Loire département of the Auvergne. This time everything went as planned and they made a blind drop on the landing ground. Although most drops were made to reception committees, some were not and these were known as blind drops. It was usually preferable for agents to be received by other agents, who could help them bury their parachutes and quickly take them away from the landing ground to ensure that if there were German patrols around they wouldn’t find them. The reception committees often took arriving agents on to a safe house, where they could rest before making their own way to the circuits they were joining. Sometimes, however, it was not practical to provide a reception committee, and it is possible that after the many problems that Southgate and Jacqueline had had in reaching France it was thought best to let them drop blind in case there were any more problems and the reception committee wasted more time in waiting for agents who didn’t arrive. Since both Southgate and Jacqueline had lived for most of their lives in France they should, in theory, have had fewer difficulties in coping with a blind drop than agents who were unused to the country.

Jacqueline jumped first and landed safely, quickly collecting up her billowing parachute in order to bury it as soon as possible and hide all traces of her arrival. As she stood up, she saw in the dim light of the French countryside the figure of a man holding a gun, which was pointed at her. On either side of the man were more figures. Jacqueline said later that she ‘felt it was very unfair to be caught so quickly’11 and that she didn’t know what to do. She walked back and forth for a moment, trying to gather her thoughts, and then heard a male voice whispering her name. She suddenly realized that the man with the gun was Southgate and that in the dark he had been unable to identify her. His companions turned out to be tree stumps.

Filled with relief that they were not about to be arrested, they quickly buried their parachutes and gathered up their bags to walk to the station in Brioude, from where they intended to take a train to Clermont-Ferrand. Although they had not been in any danger, they were both shaken by the experience, and when they came across a woman on a bike along the road, Southgate asked her for directions to the station in English. Jacqueline was horrified but quickly retrieved the situation by asking the woman the same question in French. As she did so the look of bewilderment on the woman’s face vanished, and Jacqueline realized that she had not understood what was being said to her and obviously thought that they were Germans.

They made their way to the station, a walk of nearly 32 kilometres, through the night. It should not have been so far, but in the dark they became lost and found themselves going round in circles for a time. After the encounter with the cyclist they preferred to find their own way to the station rather than ask for any more directions. On arrival, they took the first train leaving for Clermont-Ferrand. As they sank on to their seats, a German soldier came into the carriage and sat down opposite them. Jacqueline had a feeling of revulsion at having to share the carriage with him, and one of fear that he was there at all; to her it seemed as if her heart had jumped into her mouth, but she quickly recovered and opened the French newspaper that she had bought at the station and began to read it. Southgate did the same and the journey passed with no more drama.

For security reasons the details of contacts in France were given to only one person, and it was Jacqueline who had the information about where they would be able to find accommodation in Clermont-Ferrand. Leaving Southgate at a café near the station, she went to the address she had been given. A boy answered her knock on the door and she told him, ‘Je suis la fiancée d’André’ (I am André’s fiancée). The boy called back into the apartment, ‘A woman wants to speak to you,’ and André Vasseur, who was in reality George Jones (Lime) and who was known to Jacqueline from the SOE office in London, appeared. He was the wireless operator for the Headmaster circuit and would be one of those who would transmit messages for Stationer until its own wireless operator was sent from London.

The apartment at which Jacqueline had arrived, 37 rue Blatin, was the home of a family called Nerault and the boy who had answered the door was Jean Nerault. Jacqueline was welcomed into the family’s home, where she explained that she had left her circuit chief at the station and that they needed somewhere to stay for a while. She was told that they could stay there, so she went to find Southgate. He was relieved to see her, as although she hadn’t been gone for very long, it had felt like a lifetime to him and he was beginning to think that something had happened to her.12 She assured him that she was fine, although she couldn’t get used to seeing so many Germans in the streets. During the time she had been on her training courses and afterwards waiting to reach France she had had an idea of how it would be to be back in her homeland, but the reality was nothing like she had imagined. France had changed after the German invasion and she hated it, as it made her realize that she had placed herself in a very dangerous position. She also knew, though, that whatever she now felt, she would just have to cope with it: there could be no going back.

CHAPTER 4

Escape

Since the area to be covered by the Stationer circuit, from central France to the far south, was vast, nearly half of the entire country, Southgate and Jacqueline’s remit to unite the various groups in this area into efficient fighting forces, so that they would be ready when the longed-for Allied invasion of western Europe eventually began, presented a challenge. It was rather unrealistic, therefore, to have sent a new circuit leader on his first mission with an equally inexperienced courier and no wireless operator, and expect them to work miracles. Yet London could not have picked a better pair for the task.

Southgate had passed his training courses with flying colours and was highly thought of by F Section. He in turn had full confidence in his courier and was not to be disappointed when they began to work together in earnest. He was soon reporting, ‘Jacqueline is grand, and is rendering great service to my organisation and to England. I could not have done half what I have without her.’1 But although they got along very well and were soon beginning to achieve a lot of what they had come to France to do, Southgate regarded Jacqueline as a bit of an enigma. She was pleasant, polite, always did her job to the best of her ability and had a good sense of humour, but he felt that there was more to her than met the eye and that behind her pleasant façade was a woman who did not want to give away too much of her real self.

During their first few weeks in France Jacqueline and Southgate travelled tirelessly all over the large area that constituted the Stationer circuit, meeting when possible about three times each week to bring each other up to date with their progress. They soon began to establish some order among the disparate groups of resisters, and arranged training and supplies for them. Part of Jacqueline’s work as a courier was to take and fetch messages from the other groups. Before Stationer received its own wireless operator, she also had to take messages to a wireless operator of another circuit to be sent. This was a security risk for both her and the Stationer circuit as a whole, but it was nearly three months before the news reached them that the arrival of their own wireless operator was imminent.

Then, in mid-April, Amédée Maingard (Samuel) parachuted from an RAF Halifax on to a dropping zone 6 kilometres from Tarbes. Southgate met him and the two men made their way to Châteauroux, where Maingard, a Mauritian, made his base at a safe house organized for him by Jacqueline. He and Jacqueline began to meet regularly, usually at least three times a week, and his arrival made a huge difference to the efficiency of the circuit and lessened the security risk to Jacqueline, as she now only had to pass messages to one person. She always carried the messages by hand and was prepared to either destroy them or swallow them if there was any danger of her being caught. She sometimes had to carry what she referred to as ‘compromising objects’ in her bag:

If I feared an inspection at a station exit I would call a porter and get him to take my bags to the left luggage where I would collect them later. If my cases had been opened I always had enough time to disappear.

Sometimes the Germans helped me as I got off a train and gallantly carried my luggage. That helped me get through the checks without any problems.2

Southgate’s cover story for his role in the circuit was that he was an inspector and engineer for a company manufacturing gasogene,3 the gas substitute used for powering cars in France during the war. This gave him a good reason for all the travelling he undertook and sometimes gained him access to factories, which allowed him to assess the practicalities of sabotage. As a security precaution he always carried literature about his supposed employer and could speak with some authority about gasogene. Jacqueline’s cover as a saleswoman for a pharmaceutical company4 also gave her a very plausible reason for being on the move and, since the story was so close to her actual employment before leaving France to come to England, she too had few problems in maintaining the deception. But despite this the work was very dangerous.

Because of the distances she travelled, Jacqueline sometimes had to stay in hotels. This was not as easy as she had imagined. Not only did she have to avoid German soldiers without overtly appearing to do so; she also had to be on the lookout for those in plain clothes and for checks carried out by the Milice, the Vichy French volunteer paramilitary organization whose members subscribed to the abhorrent Nazi ethos. Although in her previous career she had been used to staying in hotels, she had done so as a legitimate sales representative, with genuine papers. Those she had carried when she first arrived, although excellent, were fake and one of her first tasks had been to obtain French-made documents. The day after she received her new cards she had to use them when the hotel in which she was staying in Châteauroux was subjected to a police raid.

She was washing her underwear in the basin in her room when there was a knock at the door. Believing it to be an expected visit from a member of the Resistance, Jacqueline hurriedly opened the door to be confronted by a plain-clothes policeman. Genuinely dismayed about being caught with her wet undergarments still in her hand, she began to blush and stammer her apologies for coming to the door in such a state. The young policeman was also flustered, and their mutual confusion diffused the situation. He asked for her papers, she produced them, and he gave them a cursory look before handing them back and fleeing in embarrassment.

Later that evening there was another raid and this time Jacqueline was prepared. When the knock on her door came she opened the door but pretended to have been asleep and, rubbing her eyes and yawning, asked what the policeman wanted. He mentioned Southgate, using the name under which he was known in the area – M. Philippe. Jacqueline yawned some more, and tried to look drowsy and confused. Her acting fooled him and, seeing that he would get no sensible answers from her in that state, he apologized for disturbing her and went away. She didn’t get much sleep that night. The police knew Southgate’s alias and that he was somehow linked to her. She couldn’t understand who could have told them and knew that she had to get away as quickly as possible. Not wanting to attract attention in the hotel by leaving in the middle of the night, and afraid that, if she did take that chance, the police might be keeping a watch outside, she decided to stay until the morning. As soon as it was light she took her small bag and checked out of the hotel. Later she learnt from a member of the Resistance group in the area that the police had returned just after she left, no doubt hoping to question her again when she was wide awake.

The incident proved to Jacqueline that it was not safe to stay in hotels too often and thereafter she tried to avoid them as much as possible, preferring tried and tested safe houses. But sometimes there was no other choice. On another occasion she was again disturbed twice, by two different police officers knocking at her door. She did not panic; she just showed her papers and answered their questions, and later she discovered that they hadn’t been interested in her at all. There had been a robbery in the area and every hotel room was being checked in the hope of finding the thieves.

When not taking a chance by staying in a hotel Jacqueline frequently slept during her long train journeys. More often she could only cat nap, and spent much of her time knitting socks for herself and her colleagues. On the rare occasions when she had to stay in Paris, she used her own family home there. The apartment that had belonged to her grandparents and in which the Nearne family had lived when they first came to France was empty, so Jacqueline made it available as a safe house for Southgate and other agents, although, ever cautious, she stipulated that it was not to be used very frequently. An empty apartment that had different people coming and going regularly was bound to arouse suspicion, and she wanted to avoid the possibility of it being the target of a raid.

Jacqueline’s frequent trips away from her base in Clermont-Ferrand gave her an opportunity to contact her brother Francis. He had remained in the Grenoble area, living with his wife, Thérèse, and son, Jack, at the Villa Picard in Saint Egrève, a few kilometres from the city. When, in May 1943, he heard from Jacqueline that she was back in France and would like to meet up with him, he jumped at the chance. Francis knew only that both his sisters had gone to England to look for a way to help the Allies, but when he and Jacqueline met she swore him to secrecy and told him something of what her work in France entailed. She described how difficult it was for her entire group because of the vastness of the area they covered and asked him if he would be willing to undertake ad hoc courier missions for the circuit.