Полная версия

Sisters, Secrets and Sacrifice: The True Story of WWII Special Agents Eileen and Jacqueline Nearne

Dedication

In loving memory of

Muriel Ottaway, my wonderful mother

1922–2012

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Prologue

1. Exile

2. Secrets and Lies

3. A Shaky Start

4. Escape

5. Broken Promises

6. Betrayal

7. Buckmaster Passes the Buck

8. Coming Home

9. Monumental Errors

10. An Uncomfortable Journey

11. The Deadly Discovery

12. A Bad Decision

13. A Brilliant Actress

14. Torture

15. Didi Vanishes

16. The End of the Line

17. Lost Opportunity

18. The Getaway

19. A Narrow Escape

20. Allies or Enemies?

21. Thoughtless Demands

22. Adventures, Problems and Losses

23. The Ultimate Secret Agent

Epilogue

Notes

Bibliography

Picture Section

What next?

Copyright

About the Publisher

Acknowledgements

A book of this kind could not have been written without the help of many people, and I am very grateful for all the kindnesses shown to me during the writing of Sisters, Secrets and Sacrifice.

I would like to thank Odile Nearne for sharing her memories of her aunts, Didi and Jacqueline Nearne, for allowing me to use her family photos, for sending me copies of family letters and documents, for her patience in answering my questions and for her encouragement in writing the book in the first place. She is justifiably proud of her aunts and did not want the stories of their modesty, bravery and sacrifice to die with them.

I am also very grateful to the following people: Mrs Debbie Alexander, RAF Headquarters Air Command, for the information about Frederick Nearne’s RAF career; Mr and Mrs Murray Anderson, for permission to use the photograph of pilot Murray ‘Andy’ Anderson who flew the Lysander in which Didi went to France at the start of her SOE mission; Ian M. Arrow, HM Coroner for Torbay and South Devon District; Jenny Campbell-Davys, Didi’s friend, for sharing some of her stories about her friend with me; Laurie Davidson for translating numerous French documents and letters for me, and Laurie’s friend Tony for managing to decipher some of the handwriting in letters written during the Second World War; Sharon Davidson, for her legal advice; Iain Douglas of Lisburne Crescent in Torquay; Sue Fox, excellent New York researcher, for her patience in examining files at the United Nations Archive and locating documents and information about Jacqueline Nearne’s career at the organization; Elaine Harrison at Torbay and District Funeral Service; David Haviland for his help and advice; Pat Hobrough of the Torbay and South Devon District Coroner’s office; Paul Jordan at Brighton History Centre; Bob Large, a pilot who flew SOE agents in and out of France with the ‘Moon Squadrons’; Messieurs P. Landais and Jean-Louis Landais, and Jessica Fortin who wrote to me on behalf of Mme S. Landais, all in answer to my queries about Didi’s friend Yvette Landais; Monsieur Hugues Landais, the nephew of Yvette Landais; Monsieur Pierre Landais, Yvette’s brother, for his letters and his kindness in sending me the information about his sister and her photos, and for suggesting other sources of information; Ian Ottaway, for allowing me to use his photo of the Westland Lysander; John Pentreath, Devon County Royal British Legion; Noreen Riols, a former member of the SOE, for her help; Solange Roussier, at the Archives Nationales, Paris; Susan Taylor, at the Mitchell Library, Glasgow; and Captain Rollo Young, the Army officer who helped Didi get back to England after securing her release from American custody at the end of the war.

My thanks also to my agent, Andrew Lownie, without whose help, encouragement and advice I would not have written the book at all; to Anna Valentine at HarperCollins for her enthusiasm, patience and kindness; to Anne Askwith for editing the book; and to my family for their constant support and encouragement, especially Nick, who has always been there for me, more than ever throughout this particularly difficult year.

Prologue

At the end of August 2010, after several weeks of sunshine and fine weather, a strong wind began blowing in from the sea. The hitherto blue sky disappeared to be replaced by low cloud, and the Devon resort of Torquay was subjected to an unseasonable downpour, which continued for several days.

High above the town’s harbour, in a small flat in Lisburne Crescent, an elegant Victorian Grade II listed building, lived an elderly lady, Eileen Nearne. Although 89 years old, Eileen was still quite sprightly and, despite the steep slopes of Torquay’s roads, could often be seen walking into town with her large shopping bags to fetch her groceries. Sometimes when the weather was fine she sat on a bench in the communal gardens in front of the flats, reading a newspaper and occasionally exchanging pleasantries with one or other of her neighbours. But the people who lived in the flats at Lisburne Crescent knew only two things about their neighbour: the first was that she spoke English with a foreign accent and the second, that she loved cats. They knew about her fondness for cats because she had rescued, and looked after, a ginger stray. The little animal was the only thing she ever spoke about to her neighbours and was the reason they called her, when she was out of earshot, Eileen the cat lady.

Although as the rain fell her immediate neighbours remarked to each other that they had not seen the cat lady for a few days, they were not unduly worried, reasoning that she was simply staying indoors to avoid the worst of the weather. But when the sun came out again and Eileen had still not appeared, they began to grow concerned. She had always guarded her privacy closely, so they knew that if one of them were to knock on her door to check that she was all right, she would not answer. They were uncertain what to do. Most of the neighbours thought of Eileen as a rather sad old spinster who never had visitors and did not have any family or friends. But although during the many years that she had lived at Lisburne Crescent no one had ever managed to get close to her or discover anything about her life, she was a harmless old soul and no one liked to think that she might be ill or have had a fall.

September came and Eileen was still in hiding. It was obvious by now that something had happened to her and, having no contact details or name for anyone who might be interested, one of the neighbours called the police. When they arrived they had to break into her small flat and there, on her bedroom floor, they found her body. A doctor was summoned and declared that she had been dead for several days – perhaps even a week. He ordered a post mortem and the pathologist reported to the Torquay coroner that the death was due to natural causes: Eileen had died of a heart attack brought about by heart disease and hardening of the arteries. An inquest was not necessary, so the local funeral home was contacted and preparations were set in motion for a publicly funded funeral.

The police, meanwhile, were sorting through the contents of Eileen’s tiny flat in an effort to find some evidence of family or friends. It was a difficult task. The flat was very small and filled with furniture – far too much for a home of that size. There were also cupboards filled with beautiful but rather old-fashioned dresses, ornaments, books, religious pamphlets, letters and photos. The police did not have time to read more than a few of the letters, which seemed to be old, and found nothing to suggest that she was important to anyone. The neighbours to whom they spoke could only confirm that they were not aware of any family.

Satisfied that they had done their best and that there was nothing to give any clues about her next of kin, the police were on the point of giving up the search when they came across some French coins, old French newspaper cuttings and medals. These included the British 1939–1945 Defence Medal and the War Medal 1939–1945, which were awarded to many people during the Second World War. The police took more notice when they came across the France and Germany Star, which was awarded only to those who had done one or more days’ service in France, Belgium, Luxembourg, Netherlands or Germany between 6 June 1944 and 8 May 1945 – D-Day and VE Day. They were even more surprised when they discovered an MBE and the French Croix de Guerre. Eileen Nearne in her later years may have been a rather solitary, eccentric figure but in her youth she had clearly done something special. With the clue of the medals, it didn’t take long for them to find out that she had worked for the Special Operations Executive, the secret organization that had sent agents to occupied countries during the Second World War and which had been tasked by Prime Minister Winston Churchill with ‘setting Europe ablaze’.

Her neighbours were flabbergasted. Damian Warren said that he recalled seeing a letter addressed to Eileen Nearne MBE. He said that he had asked Eileen about it and that she had dismissed it as being a mistake.1 Another of the residents, Iain Douglas, who lived at the opposite end of the crescent, said of her:

She was indeed a very strange lady, and quite reclusive. She would walk around all day with some large bags in tow and I used to wonder if she could only go into her flat at a certain time. I did wonder if she was part vagrant sometimes. She would sit outside waiting for ages. She had long, grey, unkempt hair. She would scurry away from anyone who approached her and on the sole occasion I said hello to her, she looked so shocked and horrified that I never attempted [to] again. It was a huge surprise to us when her past surfaced following her death.2

Yet another neighbour, Steven Cook, declared: ‘We thought she may have been in the French Resistance from rumours and hearsay over the years. I was very surprised at the extent of her heroism. You would never have thought it, as she never spoke of it.’3

Soon the story reached the local and then the national newspapers. Some articles said that she had been a spy; others claimed that she was just like Charlotte Gray, the eponymous heroine of Sebastian Faulks’s novel. Neither claim was true. She had in fact been a wireless operator, sending and receiving messages for the leader of a Resistance circuit in Paris, and so was clearly neither a spy nor anything like the fictional Charlotte Gray. Similar reports were given on national radio and on the television news bulletins, but still no relatives appeared.

John Pentreath, the Royal British Legion’s manager for Devon, was reported as saying: ‘We will certainly be there at her funeral. We will do her as proud as we can … She sounds like a hugely remarkable lady and we are sorry she kept such a low profile, and that we only discovered the details after her death.’4

By the time the international newspapers had taken up the story of the death of the courageous old lady, genealogists and probate researchers Fraser & Fraser had begun searching for any heirs. They soon discovered that Eileen was one of four children and that she had never married. Her sister was deceased and had also remained single, but her two brothers, who had both died in their early 50s, had married and each had had a child. The elder brother had had a son who had died in 1975 but the younger of the two brothers had had a daughter, and Fraser & Fraser believed that she was still alive.

One of the company’s researchers managed to find Eileen Nearne’s niece, Odile, in Italy. She had married an Italian and was living in Verona. A telephone call was made to her and she was informed that her aunt had died. Since everyone believed Eileen was alone and unloved, her niece’s reaction to the news was, perhaps, not quite what they had expected: Odile was distraught.

Over the years Odile had regularly come to England with her family to visit Eileen and had last seen her aunt six months before her death. Eileen Nearne was a very important figure in her niece’s life and Odile was devoted to her. She was not only inconsolable when she learnt the details of her lonely death but also horrified to discover that her aunt had been destined to have a pauper’s funeral, with no one to mourn her loss, and quickly made plans to come to England. After her arrival she took over the funeral arrangements and was able to answer many of the questions about her aunt’s life that had been puzzling the people of Torquay and reporters from around the world. And as she answered them, it soon became clear that almost everything that had been believed about Eileen Nearne was incorrect, and the true story of her amazing life, along with that of her elder sister Jacqueline, who was also an SOE agent, began to unfold.

CHAPTER 1

Exile

Eileen Nearne was born at 6 Fulham Road, west London, on 15 March 1921, the youngest of the four children of John and Mariquita Nearne. When her father registered her birth two days later, he gave her name as Eileen Marie. It seems to have been the only time in her life that her middle name was spelt this way, as all other documents refer to her as Eileen Mary – a strange choice, as Mary was also one of her sister’s names. In any case, Eileen was known to all, friends and family alike, as Didi. The name stuck and those who knew her well called her Didi for the rest of her life.

John Francis Nearne, Didi’s father, was the son of a doctor also named John1 and so, to avoid confusion, was known as Jack. He was a 23-year-old medical student when he married French-born Mariquita Carmen de Plazaola at Marylebone Register Office on 6 November 1913. Mariquita, then 26 years old, was the daughter of Spanish Count Mariano de Plazaola and his French wife, the Marquise of La Roche de Kerandraon.2 By the time Jack and Mariquita’s first child, a boy they named Francis, was born on 16 July 1914, the couple had moved from their London address, 70 Margaret Street, Marylebone, to Brighton.

With the onset of the First World War in 1914, Jack became a private in the Royal Army Medical Corps. Mariquita remained at the family home, 32 West Hill Street, a neat Victorian terraced house just a short walk from the beach. It was here that on 27 May 1916, their second child, Jacqueline Françoise Mary Josephine, was born.

After Jack’s military service ended he gave up being a doctor and became a dispensing chemist. The family left the seaside and returned to London, setting up home at 58 Perham Road in Fulham, another Victorian terraced building, and, on 20 January 1920, their second son, Frederick John, was born. The family was completed the following spring with the arrival of Didi. As the baby of the family Didi was rather spoilt and, according to her own account, she was a very naughty child.3

In 1923, with Europe still in turmoil as a result of the war, Jack and Mariquita decided to leave England and move to France. Mariquita’s parents owned several houses and apartments there, and offered the family an apartment in Paris, to which they moved with their young family.

Of all the children Francis, the eldest, was the one who had the most difficulties in adjusting to the move. He was nine years old and had already completed nearly four years of schooling in England. He couldn’t speak French but was sent to a French school in the rue Raynouard, on the right bank of the river Seine, in the hope that he would soon settle down there and learn both his lessons and the language. The school was close to his mother’s birthplace at Auteuil in the capital’s wealthy 16th arrondissement, a pleasant area his mother knew well. But Francis was not happy at school. He found the lessons complicated and difficult and, despite his mother speaking to him in French in an effort to help him, could understand only a few words. It was a good school but Francis did not do at all well and was very disheartened by his lack of progress. A shy, sensitive boy, he found it difficult to make the friends who might have made his assimilation into the French education system a little easier. He had to endure this unhappy situation for a year before his parents took him away. They looked for another school that might suit him better and enrolled him in one in Le Vésinet in the north-west of Paris where, for six months, he received intensive coaching to bring him up to the standard required for a boy of his age. It was an unfortunate start for the poor little lad, and his lack of early success damaged his self-confidence to such an extent that he never really recovered. The feeling of failure was exacerbated when his younger siblings managed to fit in at school with far fewer difficulties than he had had and he was too young to understand that it was because they had been brought to France at an earlier age than he, so their transition to the French way of life was much easier.

Jacqueline, who was seven years old when she arrived in France, had a much more straightforward time at the exclusive Convent of Les Oiseaux at Verneuil to the north-west of Paris, being only a few months behind her French classmates, who didn’t start school until they were six years old. She also found it less of a problem to speak French and quickly settled in to her new life.

The two youngest members of the family, Frederick and Didi, had not attended an English school at all, as neither was old enough, and by the time they went to French schools they were both able to speak the language as well as French children, so they didn’t have to make the adjustments their elder siblings had; their education was completely French, from beginning to end.

Mariquita was determined that all her children should be brought up in the Roman Catholic faith. She herself had been educated at a Catholic convent and she intended that both her daughters should have a similar start in life. Didi enjoyed the rituals of the Catholic Church and at a very early age she found a strong faith in God, which stayed with her all her life. Her mother never had to insist that Didi attend church services, as she went willingly without any prompting. Jacqueline once remarked that Didi was the most religious member of the entire family, although they were all believers.

Didi was never far away from her sister. She hero-worshipped Jacqueline, and wanted to be like her and do whatever she did. It must sometimes have been irritating for Jacqueline to have her little sister trying to tag along wherever she and her friends went, but she was very fond of Didi and didn’t like to turn the little girl away unless she really had to.

After two years in the French capital the family was on the move again, this time to a terraced house that had been given to Mariquita by her parents, 260 boulevard Saint-Beuve on the seafront at Boulogne-sur-Mer. Francis and Frederick attended the Institution Haffreingue, a Catholic school, while Jacqueline was enrolled at the Ursuline convent in the town, where before long Didi joined her. Didi loved her new home. It was the first time she had lived on the coast and the beginning of her lifelong love of the sea.

The house in Boulogne was a happy home and the family felt very comfortable there. Jack Nearne had attempted to learn and improve his French but had had little success. The language didn’t come naturally to him and he was not confident about speaking it. Despite living in France for the rest of his life, he couldn’t ever be described as being fluent in either spoken or written French. This rather hampered his employment prospects but, as he was part of a wealthy family following his marriage to Mariquita, it did not seem to be a major problem. His ineptitude with the language gave his children an advantage, as well as amusing them greatly, because it meant that in order to communicate with their father they had to speak fluent English as well as French, a skill that would serve them all well in their future lives.

Both parents encouraged the children to work hard at school and to read or listen to music when at home. Jacqueline and Didi were avid readers. Jacqueline liked books such as Vanity Fair, Sherlock Holmes stories and The Forsyte Saga. Didi preferred religious books and didn’t like novels at all. They both enjoyed the music of Strauss, Chopin and Beethoven and later, when they were older, that of Glenn Miller, Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin and Jean Sablon.

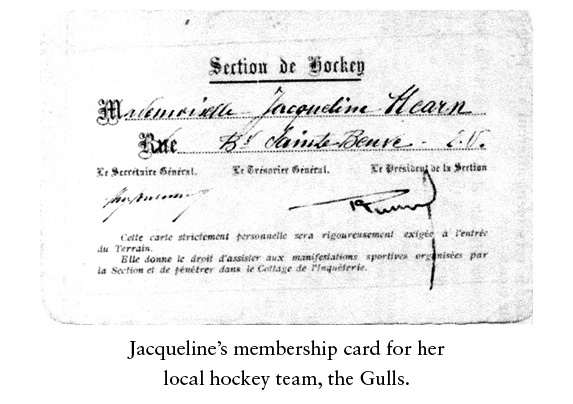

During the school holidays Jacqueline liked taking part in all kinds of outdoor activities. She loved sport and played for a girls’ hockey team called the Gulls, along with her friends Claire Turl, Marie, Jeanne and Madeleine Louchet, Anne and Marie Louise Cailliez and Nelly Pincedé. She also loved the countryside around Boulogne and cycled to local beauty spots or went for long walks with her friends. When they all got together at the home of one of the group they played cards, told each other jokes and laughed a lot. Jacqueline also liked to knit, and she made lots of colourful socks for herself and her friends.4

When she was old enough Didi also played hockey, and she and her friends laughed a lot too. They all enjoyed fooling around, no one more so than Didi, but she also had a serious side. She liked being with other people, but was also able to keep busy and was quite content when she was alone. She was good at art, and liked to paint and make little clay models; and, of course, she had her belief in God.

In 1928 Mariquita’s mother died and left her house in Nice to her daughter. By 1931 the family had packed up their belongings, closed up the house in Boulogne-sur-Mer and moved to Nice, to 60 bis, avenue des Arènes de Cimiez. Situated in the old part of Nice, in the gentle hills behind the coastline, the house was only a short distance from the seafront and the elegant promenade des Anglais, playground of the rich and famous. The family would live there very happily until the Germans invaded France in 1940.

Francis left school in 1930 when he was 16 and went on to a commercial college, where he took a business course and, having passed it, became a representative for a confectionery company. Over the next few years he had a variety of sales jobs that never seemed to last long, so, tiring of sales, he tried working as a barman. Then in 1938, against an increasingly difficult economic backdrop, he lost yet another job and, despite applying for different positions, remained unemployed for the next two years.5

Frederick left school just before the start of the war and also found it difficult to obtain work. He considered going back to England to see if it would be any easier to get a job there and was still weighing up his options when the Germans marched into Poland in September 1939. Didi had not even begun to look for work by then, as she had only just left school at the age of 18. She wanted to be a beautician, but with the political unrest that was making itself felt more and more each day, and the ever-present question of what the immediate future might bring, her parents convinced her to stay at home with them until what was happening became clearer. When the war started she gave up the idea, pushing it to the back of her mind in the belief that she would be able pursue her chosen career once the war was over.