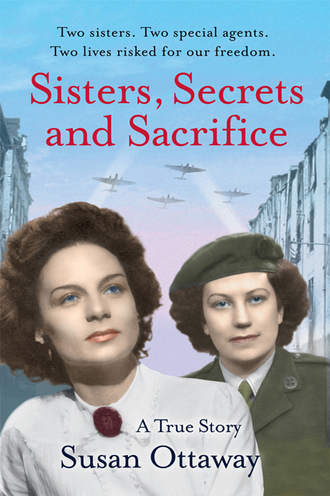

Sisters, Secrets and Sacrifice: The True Story of WWII Special Agents Eileen and Jacqueline Nearne

Полная версия

Sisters, Secrets and Sacrifice: The True Story of WWII Special Agents Eileen and Jacqueline Nearne

Язык: Английский

Год издания: 2018

Добавлена:

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента

Купить и скачать всю книгу