Полная версия

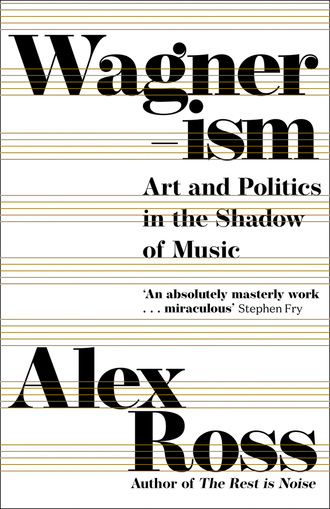

Wagnerism

With all the love of all the livelong night;

With all its hours yet singing in their ears

No mortal music made of thoughts and tears,

But such a song, past conscience of man’s thought,

As hearing he grows god and knows it not.

At the very end, Swinburne tells of how King Mark, having forgiven the lovers, builds a tomb for them—“a chapel bright like spring / With flower-soft wealth of branching tracery made.” (Burne-Jones pictured such a tomb in his contribution to the Pre-Raphaelite stained-glass project, with sculpted lovers lying side by side and two hounds keeping watch.) Swinburne then recalls that according to legend the Kingdom of Lyonesse sank into the sea. So, above the lovers’ submerged shrine, the tide “gleams and moves and moans,” and they find permanent peace in the “light and sound and darkness of the sea.” The obliterating action of the ocean plays much the same role as Tristan’s “Transfiguration,” where Isolde sinks and drowns in highest bliss.

Swinburne endured two shocks after publishing the poem he considered his best. In October 1882, Powell died suddenly at the age of forty. In February 1883, Wagner expired in Venice. In a poem titled “Autumn and Winter,” Swinburne called Powell a “herald soul,” flying up in advance of his musical god. There followed “The Death of Richard Wagner,” the noblest of the dozens of poems written in commemoration of Wagner’s death. It ends with an image of “the rising of doom divine as a sundawn risen to sight / From the depths of the sea.” These poems appeared alongside “Two Preludes: Lohengrin and Tristan und Isolde” in the 1883 volume A Century of Roundels. The British literary world had resisted Wagner, but it gave way in the end. Tristram became Tristan, Iseult Isolde.

YOUNG ADULT WAGNER

The Wagner-cultus has grown and spread of late amongst British musical amateurs to an extent that is little short of the phenomenal,” a critic said in 1881. The following year brought a Wagner wave to London, encompassing most of his mature output. A touring production of the Ring, based on the 1876 Bayreuth staging, presented three complete cycles in London; the Prince of Wales attended most of the performances, having rearranged his schedule to accommodate them. William Gladstone, the giant of British liberalism, also showed approval of Wagner. Parsifal, which was still confined to Bayreuth, acquired an especially lofty reputation in the Victorian era. Anne Dzamba Sessa, in Richard Wagner and the English, writes that the opera “bathed the listener in a soothing wash of inchoate and luxurious pious emotion.”

Later in the decade, the physician and Theosophist William Ashton Ellis launched a journal called The Meister, dedicated to the “regenerative life-force of the Spring of Richard Wagner’s genius.” Ellis also began publishing translations of Wagner’s prose writings, making the doubtful claim that even if the Meister had “never composed one bar of music, and never conceived one scene of drama, his prose works alone would have ranked him amongst the foremost thinkers of the day.” Regrettably, Ellis’s clumsy, literal, borderline-unreadable renderings of Wagner’s already intractable prose remain the standard English versions. The Meister aimed to be the counterpart to the Revue wagnérienne, but it fell on an altogether lower literary level. A few commemorative poems give sufficient flavor of the whole:

Immortal Master! earthward wing thy flight …

(Henry Knight, “In Memoriam: R. Wagner”)

I will not call thee dead, for such as thee

Death is but Life …

(Clara Grant Duff, “At Richard Wagner’s Grave”)

Thou, O Belovëd, O Master,

Magical child of the spring …

(Evelyn Pyne, “Anniversary Ode”)

Farewell, Great Spirit! Thou by whom alone,

Of all the Wonder-doers sent to be

My signs and sureties Time-ward, unto me

My inmost self has ceased to be unknown!

(Alfred Forman, “The World’s Farewell to Richard Wagner”)

Forman, a minor poet and scholar who made a living as a paper merchant, prepared the first English translations of the Ring and Tristan, which rival Ellis’s work in their alliterative opacity (“Fitly thy ravens / take to their feathers”). Isolde’s Transfiguration lapses into the lilt of a Victorian parlor song: “To drown—/ go down—/ to nameless night—/ last delight!”

Publishers in both Britain and the United States saw a market for explications of Wagner, especially ones oriented toward younger readers. These books naturally highlight the heroes-and-dragons dimension of the music dramas. In keeping with popular sensibilities, they maximize the nobility of Wagner’s characters and minimize their sins. Wonder Tales from Wagner, by the American author Anna Alice Chapin, begins its account of Tristan with the words “Once upon a time.” Isolde is “tall and very fair, with hair of a deep, brilliant gold, and clear, shining blues.” Tristan is a “deeply tanned” lad with “short, curling brown hair.” With the onset of the Night of Love, the two show apparent restraint, seating themselves upon a bank of flowers and “satisfying themselves and each other with assurances and proofs of their love and fidelity.”

Reticence was obligatory in the genre of Wagner for the Young. The composer’s less wholesome goings-on, especially the incest in the Ring, necessitated a fair amount of bowdlerization, not to mention outright falsification. The New York Times, reviewing William Henry Frost’s The Wagner Story Book: Firelight Tales of the Great Music Dramas, dryly concluded that “the emotional contents of the Wagner dramas are altogether too stupendous to lend themselves readily to reduction to child literature.” The critic noted Frost’s “masterly inactivity” on the subject of the brother-sister love in Act I of Walküre. Grace Edson Barber, in Wagner Opera Stories, omits the entire first act of that opera, saying only that Brünnhilde had defended an unnamed “brave friend” who had “not been true to all the laws.” Chapin mentions the twins in The Story of the Rhinegold, but slyly disguises their relationship, saying, “They loved each other as much as though they had been really brother and sister.”

Götterdämmerung posed another challenge: how could young people be expected to cope with the self-immolation of Brünnhilde and the incineration of Valhalla? In Barber’s telling, Brünnhilde manages to return the Ring to the Rhinemaidens without having to ride into the pyre. She exclaims, “The transformation is coming!,” whereupon, after a few days of darkness, “the birds awoke and caroled glad songs of love.” Florence Akin, a former schoolteacher from Pasadena, California, performs even more drastic surgery in her Opera Stories from Wagner: A Reader for Primary Grades, allowing the survival not only of Brünnhilde but also of Siegfried. The lovers deposit the Ring in the Rhine, whereupon “hurry, worry, falsehood, greed, and envy vanished from the earth.”

A few contributors to the Wagner youth market delved deeper. Dolores Bacon, in Operas Every Child Should Know, briskly confronts the racist question: “Probably no stupider thing was ever said or done than that by Wagner when he wrote a diatribe on the Jew in Art.” Constance Maud, the author of Wagner’s Heroes and Wagner’s Heroines, hints at Wagnerian feminism, of which more will be said in Chapter 7. The daughter of a British clergyman, Maud was involved in the suffrage movement and, in 1911, published a fiery feminist novel titled No Surrender. She makes sure that her young readers register Brünnhilde’s “commanding tones,” her “tone of queenly authority.” Furthermore, she gives glimpses of Wagner’s revolutionary agenda. When Valhalla burns, Maud perceives that Wotan has fallen victim to “the love of power and the love of gold.” There are few blunter summations of the Ring, for adults or children.

WAGNER IN AMERICA

Herman Matzen’s statue of Wagner in Edgewater Park, Cleveland, erected in 1911

In his final years, Wagner flirted with the notion of immigrating to the United States, a place he never saw. Reeling from the financial disaster of the first Bayreuth Festival, he spoke of selling Wahnfried and moving with his family to the New World. Cosima wrote in her diary: “America?? Then never again a return to Germany!” In 1879, the North American Review published an essay attributed to Wagner, positing the New World as an idyll where the “unconquerable vigor and strength” of the German spirit would find new life. Although the essay was ghostwritten by Hans von Wolzogen, the Bayreuther Blätter editor, it reflected Wagner’s outlook: his disappointment in the new Reich; his belief in the indestructibility of “holy German art”; his concerns about racial intermixing; and his fantasies of cultural rebirth. In the same period, he described his Bayreuth idea as “a kind of Washington for art”—comparing the festival to the American capital that rose on swampy land by the Potomac River.

By 1880, the American plan had become an idée fixe. Cosima wrote: “Again and again he keeps coming back to America, says it is the only place on the whole map which he can gaze upon with any pleasure.” He went so far as to draft a financial prospectus, in consultation with Newell Sill Jenkins, his American-born, German-based dentist. The idea was that American supporters would raise a million dollars—around twenty-five million in today’s currency—to resettle Wagner and his family in “some State of the Union with favourable climate.” In return, the United States would receive earnings from Parsifal and all other future work. “Thus would America have bought me from Europe for all time.” The pleasant climate he had in mind was, curiously, Minnesota.

The conceit was not as absurd as it seems. Around a million Germans had immigrated to the United States between 1846 and 1855. They were often called Forty-Eighters, because many had fled after the failed 1848 revolutions, and they played a pivotal role in American politics before the Civil War. Predominantly liberal in their thinking, they tended to support Lincoln and the Union cause. The most illustrious of them was Carl Schurz, who fought as a Union general, became a senator from Missouri, and served as the secretary of the interior under President Rutherford B. Hayes. (Wagner approved of Schurz, saying that he showed “what a proper German can do.”) Another significant Forty-Eighter was Hugo Wesendonck, who left Germany under the threat of a death sentence and proceeded to make a fortune in the life-insurance business. His company, Germania, thrives today, under the name Guardian. Wesendonck’s brother Otto, who funded Wagner during his Zurich years, was a partner in a textile-import firm that had its headquarters in lower Manhattan. The money that kept Wagner afloat for a time was American in origin.

The image of Wagner in America is amusing to contemplate—it might make for a lively historical novel—but it never came close to reality. The talk of exile may have been a ploy intended to whip up support from sources closer to home. Ludwig II, among others, took fright when he learned of the scheme, and wrote to the composer: “Your roses cannot thrive in America’s stony soil, where self-seeking, callousness, and Mammon reign.” With a certain amount of adaptation, Wagner indeed took hold across the Atlantic. In time, a full-blown cultus arose, to the point that streets were named after his characters—at least four American towns have a Parsifal Place—and statues of him were erected in parks in Cleveland and Baltimore. The monuments still stand, despite occasional calls for them to be removed.

Each country saw Wagner through a self-fashioned prism. For the French, he was a torchbearer of the modern; for the British, a messenger of Arthuriana. In the United States, Wagner harmonized with a national love of wilderness sagas, frontier lore, Native American tales, stories of desperadoes searching for gold. Joseph Horowitz, the leading historian of American Wagnerism, cites Frederick Jackson Turner’s conception of the frontier, according to which “coarseness and strength combined with acuteness and inquisitiveness” define the nation’s self-image. In much the same vein, the New York critic Henry Krehbiel contended that American operagoers saw themselves reflected in the “rude forcefulness” of Wagner’s heroes. Siegfried, especially, stirred sympathy with his “unspoiled nature,” his freedom from “false and meretricious” habits. Wagnéristes said that France was the composer’s true homeland; Yankee Wagnerites made the same claim. The historian and memoirist Henry Adams wrote that the “paroxysms of nervous excitement” surrounding the Ring at the Met showed that “New York knew better than Baireuth [sic] what Wagner meant.”

At the same time, Wagner allowed the young nation to prove itself as a maturing global power. Great American cities such as New York, Boston, and Chicago, aspiring to rival European capitals in cultural richesse, nurtured symphony orchestras and opera houses alongside museums and architectural monuments. Wagner productions, notably the Metropolitan Opera’s 1903 staging of Parsifal, were among the most opulent entertainments of the American fin de siècle. That program of self-improvement conformed to what the philosopher George Santayana called the “genteel tradition”—the American counterpart to Victorian propriety.

With his usual double-sidedness, Wagner spoke both to the crude vigor of American enterprise and to the yearning for refinement and uplift. The spiritual dimension of his work received special emphasis, joining a national mania for alternative religions and therapies: Theosophy, New Thought, Christian Science, the Chautauqua movement. The agnostic orator Robert Ingersoll loved Wagner, too: “I would rather listen to Tristan and Isolde—that Mississippi of melody—where the great notes, winged like eagles, lift the soul above the cares and griefs of this weary world—than to all the orthodox sermons ever preached.”

The American quest for heroic self-definition was caught up in questions of gender and race. Theodore Roosevelt, with his “Rough Rider” persona, epitomized an American masculinity that resisted a supposed European tendency toward effeminacy and degeneracy. Furthermore, the country’s striving for global influence and its pursuit of Manifest Destiny coincided all too often with ideologies of Aryan and Anglo-Saxon racial superiority. Herbert Spencer, the theorist of social evolution, visited the United States in 1882 and predicted that its Aryan stock would “produce a finer type of man than has hitherto existed.” Roosevelt was vulnerable to this kind of thinking; in 1911, he bemoaned “loose and sloppy talk about the general progress of humanity, the equality and identity of races.” Wagner’s work and ideas provided fodder for both sides of a battle over American identity that is ongoing.

STAR-SPANGLED WAGNER

Wagner’s music arrived in the United States in the luggage of the Germania Musical Society—two dozen radical-minded musicians who formed a collective in Berlin in early 1848 and then emigrated en masse. As Nancy Newman relates in her history of the group, the Germania aimed to create a musical-social utopia, a band of free individuals tied together by fellow feeling. Believing that “communism was the most perfect principle of society,” they adopted the ideals of “one for all and all for one,” of “equal rights, equal duties, and equal rewards.” They contrasted this picture of musical leveling with what they saw as the egotistical mannerisms of solo virtuosos in the employ of the upper classes. The Germanians hoped that their performances of composers from Bach to Wagner would “enflame and stimulate in the hearts of these politically free people … love for the fine art of music.”

In 1852, the Germanians played an excerpt from Tannhäuser in Boston. The following year, in the same city, they organized a Grand Wagner Night, augmenting selections from Rienzi, Tannhäuser, and Lohengrin with Rossini and Bellini arias. The New England poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, soon to write his Native American epic The Song of Hiawatha, was there, and wrote in his diary: “Strange, original, and somewhat barbaric.” The Germanians toured widely with this repertory, and news of their activities reached the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, one of whose contributors, Richard Pohl, made this prediction: “Wagner, the man of the liberal arts and the man of the future, will rise anew in the land of freedom and the future, and find a permanent home.” The essay ends with the sentence “Westwards moves the history of art!” The composer proudly noted, “In Boston they are now even presenting Wagnernights, evening concerts at which only my own compositions are performed.” He did not know about the Rossini and Bellini.

The Germania disbanded in 1854, but its influence lingered, especially in New York City. Carl Bergmann, one of its leaders, began conducting the Philharmonic Society of New York in 1855, causing excitement there with performances of Wagner. Four years later, Bergmann led a full staging of Tannhäuser at the Stadttheater, on the Bowery, which catered to German immigrants. Despite less than ideal conditions—the theater was small and grubby, one critic said, with boys selling glasses of beer and chunks of cheese—the opera gained respectful reviews.

Wagner did not lack for critics in the American press, although they were milder than their European counterparts. John Sullivan Dwight, the publisher of Dwight’s Journal of Music, frequently objected to the composer’s ideas, but he did a fair job of explaining them. An idealist with ties to Transcendentalism, Fourierism, and the utopian Brook Farm community, Dwight saw music as a means of moral improvement and social reform. At first, the new import piqued his interest. “Verily here is a deliberate attempt to Wagnerize us,” he wrote in advance of the Germania’s Wagner Night. “But why shall we not test the new sometimes, by the old?” In the event, Dwight found the music too taxing, and as he got to know Wagner’s writings his doubts increased. In 1869, when “Jewishness in Music” was republished, he spent several pages denouncing its “ignoble and small-minded statements” against Jews.

Wagner’s most decisive advocate in the post–Civil War years was the German-born conductor Theodore Thomas, who came to the United States with his family in 1845, when he was ten. Thomas was one of the first modern conductors—a strong-willed podium technician in the lineage of Berlioz, Wagner, and Hans von Bülow. Thomas’s first orchestral concert, in New York in 1862, began with the Flying Dutchman overture. In subsequent years, he led the Philharmonic Society of New York and the Brooklyn Philharmonic, and in 1891 he helped found the Chicago Symphony. Thomas often included Wagner excerpts on the summertime concerts that he led in the Central Park Garden, starting in the late sixties. In 1872, he presented “The Ride of the Valkyries,” using a copy of the manuscript. “The people jumped on the chairs and shouted,” he wrote in his memoirs. The “Ride” was already a hit in Europe, despite Wagner’s intermittent disapproval of the practice of playing excerpts.

In 1876, on the occasion of the hundredth anniversary of American independence, Thomas succeeded in commissioning an American Centennial March from Wagner himself. The fee was five thousand dollars—equivalent to more than one hundred thousand dollars today. After haggling over rights, Wagner produced a work of thoroughgoing mediocrity, its most promising musical idea set aside for the Flower Maidens scene in Parsifal. The premiere took place at the opening of the Centennial Exhibition, in Philadelphia. Despite the dreariness of the music, the response was generally warm. According to one press report, Wagner had honored the “feminine loveliness, noble natures, and pure mental activity of American women”—the march was dedicated to the Women’s Centennial Committee—and evoked “a world of souls communing together in universal concord.”

The rising young composer and bandmaster John Philip Sousa added a Wagner twist to his own centennial composition, a medley of national airs titled International Congress Fantasy. The piece culminates in a festive orchestration of “The Star-Spangled Banner” in the style of the Tannhäuser overture, with stuttering motifs accompanying the principal theme. In a band arrangement, the anthem is marked “à la Wagner.” Sousa once told an interviewer, “My two most popular pieces are the ‘Tannhaeuser Overture’ and the ‘Stars and Stripes.’” He added: “Wagner was a brass band man, anyway.” When he took charge of the U.S. Marine Band, in 1880, the March King regularly programmed Wagner on official occasions, including that of the inauguration of President Grover Cleveland, in 1885.

Wagner had impinged on the American presidency before. Ulysses S. Grant was present for the premiere of the American Centennial March, though he famously had no ear for music. (“I only know two tunes: one is ‘Yankee Doodle’ and the other isn’t,” he supposedly once said.) Rutherford B. Hayes, Grant’s successor, hosted musicales at the White House, including piano performances by his secretary of the interior, Carl Schurz. On at least one occasion, the First U.S. Cavalry Band serenaded Hayes with a Wagner selection. Cleveland, who served two discontinuous terms as president, apparently liked Wagner, and his young wife, Frances Folsom, was a conspicuous enthusiast. Sousa’s Marine Band played the Bridal Chorus at the Clevelands’ wedding, in 1886, and later performed selections from Lohengrin on the White House lawn, with the First Lady sitting enthralled at a window.

American Wagnerism entered its peak phase in 1884, when Theodore Thomas marshaled a grand tour of seventy-four Wagner concerts in twenty North American cities, employing monster choruses and drawing audiences as large as eight thousand people. The success of that endeavor caught the attention of a fledgling New York company, the Metropolitan Opera, which had opened the previous year and immediately run into financial trouble. For the second season, the Met board, led by James A. Roosevelt, Theodore’s uncle, decided to switch from Italian opera to German fare. The émigré conductor Leopold Damrosch, well acquainted with Wagner, was engaged as music director. Tannhäuser, Lohengrin, and Walküre formed the core of the repertory, the last causing a sensation that probably ensured the survival of the house.

When Damrosch died suddenly of pneumonia toward the end of his first season, the Met brought in Anton Seidl, a greatly gifted young conductor who had assisted Wagner in Bayreuth. The company kept to an all-German format until 1891: out of nearly six hundred performances in that period, more than half were of Wagner. In the 1888–89 season, Seidl led the first American Ring, and subsequently took the cycle on tour, as he had done with the Bayreuth Ring in Europe. In St. Louis, the Ring was advertised, in the P. T. Barnum manner, as “THE GREATEST OPERATIC ATTRACTION IN THE WORLD.” The Wagner mania reached across the continent to San Francisco, and even penetrated the Francophone bastion of New Orleans, where Rex, the King of Carnival, brought his masked retinue to a gala performance of Lohengrin.