Полная версия

Post Wall, Post Square: Rebuilding the World after 1989

Although this was for the moment a transitional government – free elections would not be held until June 1990 – the transformation was truly profound. This had been a ‘Velvet Revolution’: smooth and swift, on occasion even merry. By comparison with Poland, Hungary and GDR, opposition politics in Prague had been improvised by amateurs – but they had been able to learn from the mistakes of the others, as well as from their successes. And what’s more, revolution in Czechoslovakia came without the pain of deepening economic crisis, with which the new governments in Warsaw and Budapest had to grapple. And so by the New Year, Czechoslovakia found itself firmly on the road towards political democracy and a market economy.[167]

So much had changed in only two months. At the start of November 1989, it was still possible in Eastern Europe to imagine a future for communism, albeit in a reformed state. But within weeks no one could doubt that it was in irreversible decline. And by the end of the year ‘those who had come too late’, as Gorbachev put it in East Berlin, had most certainly been punished (Ceaușescu, Zhivkov and Honecker), while those who had never let themselves be silenced (notably Havel and Mazowiecki) had now replaced the leaders they previously denounced.

The fact that Gorbachev presided over these variegated national exits from communism without intervening also allowed Kohl more leeway and gave hope for his mission in 1990: to bring the two Germanies closer to unity. The chancellor set the tone in his New Year message, expressing the aspiration that the coming decade would be ‘the happiest of this century’ for his people – offering ‘the chance of a free and united Germany in a free and united Europe’. That, he said, ‘depended critically on our contribution’. In other words, he was reminding his fellow Germans – so long weighed down by the burden of the past – that they had now been given the opportunity to shape the future.[168]

But the new architecture could not be constructed by Germans alone. With the communist glacier in retreat – indeed melting before one’s eyes – and the ascendant Western Europe opening out, the stark, two-bloc structure of Cold War Europe had cracked asunder. The pieces would now have to be put together in a new mosaic and this would require not merely the consent but also the creative engagement of the superpowers.

In other words, Kohl might have had his problems with Mitterrand and especially Thatcher, but they were mere stumbling blocks. When it came to building a new order around a unifying Germany, this could be achieved only by working with Bush and Gorbachev. Yet both these leaders were deeply preoccupied in late 1989 with their own problems: how belatedly, to create an effective personal rapport after their slow, at times frosty, start. And, more than that, how to manage the delicate business of moving beyond the Cold War in the heart of Europe.

Chapter 4

Securing Germany in the Post-Wall World

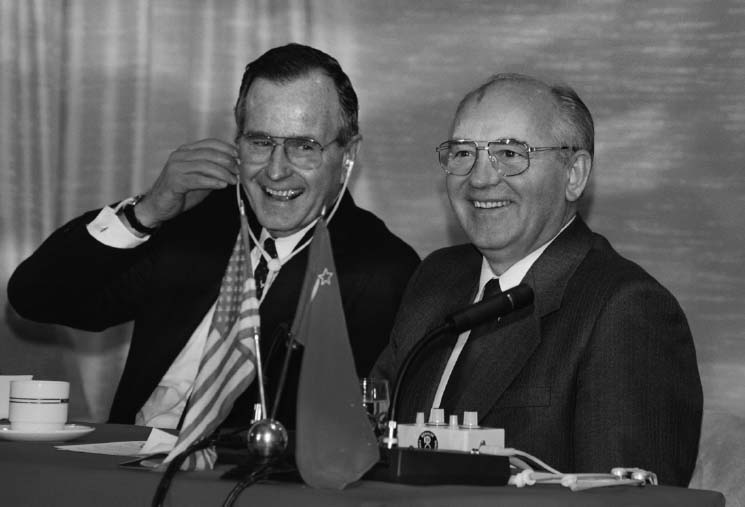

The 3rd of December 1989. It was almost incredible. George Bush and Mikhail Gorbachev, the leaders of the United States and the Soviet Union, sitting together in Malta, relaxed and joking, in a joint press conference at the end of their summit meeting. This was a month after the fall of Wall and barely a week after Kohl’s surprise announcement of his Ten-Point Plan in the Bundestag.

Happy days: Bush and Gorbachev on the Maxim Gorky

‘We stand at the threshold of a brand-new era of US–Soviet relations,’ Bush declared. ‘And it is within our grasp to contribute, each in our own way, to overcoming the division of Europe and ending military confrontation there.’ The president was optimistic that together they could ‘realise a lasting peace and transform East–West relations to one of enduring cooperation’. This, said Bush, was ‘the future that Chairman Gorbachev and I began right here in Malta’.[1]

The Soviet leader fully agreed. ‘We stated, both of us, that the world leaves one epoch of Cold War and enters another epoch. This is just the beginning. We’re just at the very beginning of our long road to a long-lasting peaceful period.’ Looking ahead he stated bluntly: ‘the new era calls for a new approach … many things that were characteristic of the Cold War should be abandoned’. Among them ‘force, the arms race, mistrust, psychological and ideological struggle … All that should be things of the past.’[2]

At Malta, there were no new treaties, not even a communiqué. But the message of the summit was clear – symbolised in this first ever joint press conference of superpower leaders. The Cold War, which had defined international relations for over forty years, seemed to be a thing of the past.

*

A full year had elapsed since these two men last met, at Governors Island, New York, in 1988 when Reagan was still president. Then Bush had assured Gorbachev that he hoped to build on what had been achieved in US–Soviet relations but would need ‘a little time’ to review the issues. That ‘little time’ had turned into twelve months, during which the world had been turned on its head.[3]

Bush’s initial diplomatic priority had been to pursue an opening with China, but this was much more difficult post-Tiananmen. It was only after his European tour – the NATO summit in May and his trips to Poland and Hungary in July – that the president really began to grasp the magnitude of change in Europe. With the language of revolution ringing in his ears as he witnessed the bicentennial celebrations of 1789 during the G7 summit in Paris, he decided it was finally time to propose a meeting with Gorbachev to develop a personal relationship in order to manage the growing turmoil. This was a veritable ‘change of heart’ – indeed, as Bush would later admit in Malta, a turn of ‘180 degrees’.[4]

The Soviet leader, of course, had always been keen to meet, but it was not possible to agree firmly on date and place until 1 November. And by the time they actually met one month later, the Iron Curtain was a thing of the past: East Germany was dissolving, a palace coup had taken place in Bulgaria, and Czechoslovakia’s Velvet Revolution was in full swing. Bush worried that political leaders might not be able to control this remarkable revolutionary upsurge. In particular, he feared that Gorbachev could still be pushed into using force to hang on to the bloc and shore up Soviet power. That is why the president resisted the temptation to celebrate the triumph of democracy – to the puzzlement of many Americans, especially in politics and the press. Bush felt it was in the American national interest, first, to help Gorbachev stay in power, given his continued commitment to reform and, second, to keep US troops in Europe to maintain American influence over the continent. With the geopolitical map in flux, a meeting of minds between the superpowers had become vital for the peaceful management of events. That is why he and Gorbachev needed to talk, even if they had no agreements to sign.

Ten days before their encounter, on 22 November, Bush cabled the Soviet leader: ‘I want this meeting to be useful in advancing our mutual understanding and in laying the groundwork for a good relationship.’ More, ‘I want the meeting to be seen as a success.’ He insisted: ‘Success does not mean deals signed, in my view. It means that you and I are frank enough with each other so that our two great countries will not have tensions that arise because we don’t know each other’s innermost thinking.’[5]

The two sides had already agreed that it would be a ‘no agenda’ meeting, but the president wanted Gorbachev to have a general idea of what he had in mind. He listed six key topics: Eastern Europe; regional differences (from Central America to Asia); defence spending; visions of the world for the next century; human rights; and arms control. ‘Of course,’ Bush added, ‘you will have your own priorities.’[6]

The president clearly sought the freedom to improvise in Malta. This horrified Scowcroft and the NSC staff who had never wanted a summit with no agenda. They feared another Reykjavik, when – so they believed – Reagan had got seduced by Gorbachev. In their eyes it was imperative to save Bush from falling for the Kremlin’s smooth talker who with sweet words like ‘peace’, ‘disarmament’, and ‘cooperation’ had gained a huge cult following in the West. Most of the president’s entourage believed that if Bush could be persuaded to work from a firm agenda based on ‘a package of initiatives on every subject’, that would put Gorbachev on the defensive. And it would help them to keep the president on a tight leash and minimise the dangers – at such a pivotal moment in history – of ill-advised American concessions.[7]

Bush and Gorbachev flew to Valletta with their foreign ministers and a few key advisers. Their weekend of talks, held on Saturday and Sunday 2–3 December 1989, were originally intended to move to and fro between an American and a Soviet battle-cruiser. But a massive storm blew up and so the venue was moved to the huge Soviet passenger liner Maxim Gorky, safely moored in Valletta’s great harbour. Even so, the Saturday afternoon and evening sessions had to be cancelled. Bush jotted down in his diary: ‘It’s the damnedest weather you’ve ever seen … the highest seas that they’ve ever had, and it screwed everything up … The ship is rolling like mad … Here we are, the two superpower leaders, several hundred yards apart, and we can’t talk because of the weather.’ Scowcroft recalled: ‘Gorbachev could not reach the Belknap [i.e. the US cruiser] for dinner that evening, so we ate a marvellous meal meant for him – swordfish, lobster, and so forth.’[8]

But in spite of the stormy weather, president and general secretary managed to spend most of the two days in calm and fruitful discussion. They clicked right from the start. Bush even approved of Gorbachev’s taste in clothes, noting in his diary: ‘He wore a dark blue pinstripe suit, a cream-coloured white shirt (like the ones I like), a red tie (almost like the one out of the London firm with a sword).’ And, the president added, he had a ‘nice smile’.[9]

In the first plenary the Soviet leader proposed that they should develop ‘a dialogue commensurate with the pace of change’ and predicted that, although Malta was officially just the prelude to a full-scale summit the following summer, it would have ‘an importance of its own’. Bush agreed, but he then tried to cut through the standard Gorby grandiloquence. Getting down to brass tacks, he spelled out the specific ‘positive initiatives’ by which he hoped to ‘move forward’ into the 1990 summit.[10]

The president assured Gorbachev that he believed the world would be ‘a better place if perestroika succeeds’. To this end, he said he would like to waive the Jackson–Vanik amendment, which since 1974–5 had prohibited open economic relations with the Soviet bloc. Trade negotiations combined with export credits would, he declared, enable the USSR to import the modern technology that it needed. ‘I am not making these suggestions as a bailing out’, Bush insisted, but in a genuine spirit of ‘cooperation’.[11]

In similar vein, the president was now ready to act openly as an advocate for Soviet ‘observer status’ in the GATT, ‘so that we can learn together’. He promised to support Moscow’s aspiration, after completion of the latest round of multilateral trade renegotiations – the so-called Uruguay Round – between the 123 contracting members. Joking that the prospect of early Soviet association might even serve as an ‘incentive’ to EC countries to end their ‘fighting’ between themselves and with the USA over the vexed theme of ‘agriculture’, he recommended that meanwhile the Kremlin ‘move toward market prices at wholesale level, so that Eastern and Western economies become somewhat more compatible’. At this point Bush hoped the Uruguay Round would be completed in less than a year.[12]

Gorbachev, equally optimistic about his country’s prospects to speedily join in global trade, was keen to ‘get involved in the international financial institutions’. He stressed: ‘We must learn to take the world economy into perestroika.’ And he truly appreciated US ‘willingness to help’ the Soviet Union to open out. But he was also adamant that the Americans should stop suspecting the Soviets of wanting to ‘politicise’ these organisations. Times had changed, he said, averring that both sides had abolished ‘ideology’, so now they should ‘work on new criteria’ together.[13]

It wasn’t all sweetness and light, however. The president touched on human rights (and the issue of divided families) before turning to the Cold War hotspots of Cuba and Nicaragua. He told Gorbachev to stop giving Fidel Castro cash and arms. The Cuban leader was ‘exporting revolution’ and exacerbating tensions in Central America, particularly Nicaragua, El Salvador and Panama. Prodding Gorbachev, he said that ordinary Americans were asking how the Soviets could ‘put all this money into Cuba and still want credits?’ Finally, Bush moved to the area of arms control, emphasising his hopes for a chemical-weapons agreement, the completion of a conventional forces in Europe (CFE) treaty and strategic arms-reduction treaty (START) in 1990.[14]

Gorbachev answered with a tour d’horizon of his own. He stated that ‘all of us feel we are at a historic watershed’: international politics is shifting from a ‘bipolar’ to a ‘multipolar’ world, while the whole human race is facing truly global challenges such as climate change. Specifically, the American and Soviet peoples were following a strong desire to ‘move toward each other’; governments, however, were lagging behind. Gorbachev strongly objected to the Cold War triumphalism he felt was present in US government circles. Acknowledging that Bush had shown he was different, Gorbachev now sought in a formal way the respect of the United States. He was emphatic that he did not wish to be lectured or put under pressure by the Americans. What he wanted was to ‘build bridges across rivers rather than parallel to them’; he looked for new approaches and new ‘patterns of cooperation’ that befitted the ‘new realities’. He also referred back to the productive, cooperative relationship he had eventually managed to establish with Ronald Reagan despite ‘times of impasse’. He still wanted arms control but, furthermore, he wanted the USSR to get involved in the world economy at large. This was surprising talk coming from a Soviet leader.[15]

A lot of the first plenary session was the usual for-the-record mutual positioning and ideological point-scoring that occurred at the start of any superpower meeting. But behind their rhetoric were already hints of something more personal and significant. Bush deliberately reached out to Gorbachev. ‘I hope you have noticed that as dynamic change has accelerated in recent months, we have not responded with flamboyance or arrogance … I have conducted myself in ways not to complicate your life.’ That’s why, he added, ‘I have not jumped up and down on the Berlin Wall.’[16] Gorbachev appreciated Bush’s refusal to inflame passions. He made an equally striking observation: ‘The US and the USSR are doomed to cooperate for a long time,’ but, in order to cooperate fruitfully, ‘we have to abandon the vestiges of images of an enemy’.[17] ‘Doomed to cooperate’ was a striking phrase. Here was an echo of Reykjavik 1986, when Gorbachev had stated: ‘As difficult as it is to conduct business with the United States, we are doomed to it. We have no choice.’[18] It betrayed a negative-positive approach to relations, reflecting the abiding Russian angst about whether assertion against the West or integration within the world was the key to national identity and international status.

The two leaders really got down to business in their one-on-one meeting – held with only an adviser and an interpreter from each side, after a short break. What exercised Gorbachev above all were Washington’s operations in its Latin American backyard. He made the provocative suggestion that Cuba and the US should normalise relations, and then complained about US intervention in ‘independent countries’. Bush tried to brush all this aside, waxing eloquent about America’s war on drugs in Panama and Colombia and reminding the Soviet leader that it was a democratic government in Manila that had asked America for help against Filipino rebels. Carrying on the tit-for-tat, Gorbachev retaliated: ‘in the Soviet Union some are saying the Brezhnev Doctrine is being replaced by the Bush Doctrine’. He stressed that he was an advocate of ‘peaceful change’ and ‘non-interference’ (as exemplified by his conduct in Eastern Europe). This new Soviet attitude, he insisted to Bush, was ‘bringing us closer’.[19]

Having spent most of the session jousting about the global Cold War, Gorbachev finally zeroed in on Germany. ‘Mr Kohl is too much in a hurry on the German question,’ Gorbachev exclaimed. ‘This is not good.’ He insisted that German unification was not something the USSR would endorse. ‘There are two states, mandated by history.’ Nor did the Soviet leader want to speculate about Germany’s future within or outside alliances such as NATO. Such talk was ‘premature’, he declared: ‘let history decide what happens. We need an understanding on this.’ Vehemently, Gorbachev urged Bush to help restrain the enthusiasm for rapid unification that the German chancellor had unleashed through his Ten-Point Plan the week before.[20]

Such an outburst was typical of every Gorbachev summit. Bush tried to calm things down, saying that Kohl’s rhetoric was understandably ‘emotional’ given recent events. He promised the Soviet leader ‘we will do nothing to recklessly try to speed up reunification’. At this point, both men were in agreement that there would be no quick fix for the German question, nor would it be fixed by the Germans alone. They were united in seeing this as a time of both ‘great opportunity’ and also ‘great responsibility’ for all concerned. This dualism of opportunity and responsibility would be a continuing theme of their relationship as superpower leaders.[21]

Gorbachev was equally concerned about ideological rivalry. He wanted Bush to change his outlook and his entire rhetoric about Soviet–American relations. Perestroika and glasnost were intended to rejuvenate the USSR while placing its continued competition with the USA on a peaceful footing. His long-term aim was to bring Soviet society in line with the rest of Europe and integrate it into the global community. He envisaged a modernised, ‘socialist democratic’ Soviet Union for the twenty-first century. But this transformation, he insisted, required the West to abandon its rooted view of the Soviets, and indeed tsarist Russia, as alien from the West. Gorbachev vehemently protested that the USSR was being falsely blamed for ‘exporting ideology:’ he told Bush flatly that he had renounced revolution. And he totally dismissed the idea of ‘some US politicians’ – though ‘not you’, he assured the president – who say that the ‘unity of Europe should occur on the basis of Western values’. Germany and values were really hot topics, to which they would return the following day.[22]

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.