Полная версия

Post Wall, Post Square: Rebuilding the World after 1989

One worry was the French announcement on 22 November that Mitterrand would visit the GDR on 20 December. Why now? Ostensibly his trip was simply to reciprocate Honecker’s visit to Paris in January 1988 but Kohl was aggrieved that he – the most interested party – was being upstaged. At a deeper level, he felt that the French president was being two-faced – professing support for Kohl and the drive for unity yet apparently cultivating a failing state for France’s own benefit. Moreover, on 6 December Mitterrand had met Gorbachev in Kiev to talk over Germany and Eastern Europe. Getting to the GDR ahead of Mitterrand was therefore the main reason for fixing the Kohl–Modrow meeting for the day before.[140]

On 8 December, there was another bombshell. Kohl learned that the ambassadors of the Four Powers were going to meet in Berlin to discuss the current situation. And not merely in Berlin but in the Allied Kommandatura – notorious to Germans as the centre of the occupation regime of the 1940s and a venue not used since 1971 when the Quadripartite Agreement on access to the city had been signed. The Soviets, apparently taking advantage of the EC summit, called for the discussion to be held on 11 December, just three days later. Asked if Bonn would be displeased about the meeting, a senior French official retorted: ‘That is the point of holding it.’ The Kohl government was indeed furious; its anger subsided only when the Americans promised to make sure that the agenda was limited to Berlin rather than straddling the German question as a whole. On the day itself, robust diplomacy by the Americans was required to kill off this rather crude Russian ploy to give the Four Powers a formalised role in deciding the German question.[141]

Coming just a few days after Gorbachev’s explosion to Genscher, the Soviet powerplay at the Kommandatura persuaded the chancellor that he had to make a determined effort to explain his Ten Points to Gorbachev and disarm Soviet criticism. He instructed Teltschik to draft a personal letter to the Soviet leader, eventually running to eleven typescript pages laying out a very carefully constructed argument.

In it Kohl explained that his motivation for the Ten Points had been to stop reacting and running after events, and instead to begin shaping future policies. But he also insisted that his speech was couched, and must be understood, within the wider international context. He referred specifically to the ‘parallel and mutually reinforcing’ process of East–West rapprochement as evidenced at Malta, closer EC integration as agreed in Strasbourg, and the likely shifts of the existing military alliances into more political forms and what he hoped would be the evolution of the CSCE process via a follow-up conference (Helsinki II). In these various processes, the chancellor emphasised, his pathway to unity would be embedded. He added that there was no ‘strict timetable’, nor had he set out any preconditions – as Gorbachev wrongly alleged. Rather the speech gave the GDR options and presented a gradual, step-by-step approach that offered a way to weave together a multitude of political processes. Kohl then summarised the ten points in detail before stating at the end of the letter that he sought to overcome the division of both Germany and Europe ‘organically’. There was no reason, he insisted, for Gorbachev to fear any German attempts at ‘going it alone’ (Alleingänge) or ‘special paths’ (Sonderwege), nor any ‘backward-looking nationalism’. In sum, declared Kohl, ‘the future of all Germans is Europe’. He argued that they were now at a ‘historical turning point for Europe and the whole world in which political leaders would be tested as to whether and how they had cooperatively addressed the problems’. In this spirit, he proposed that the two of them should discuss the situation face-to-face, and offered to meet Gorbachev wherever he wanted.[142]

This weighty letter, however, appeared to have no effect. On 18 December, the evening before his visit to Dresden, the chancellor received a letter from Gorbachev. Kohl assumed this would be a reply but Gorbachev addressed other issues.[143] In a brusque two pages the Soviet leader referred only to the Genscher visit and reiterated the USSR’s view that the Ten Points were virtually an ‘ultimatum’. Like the GDR, he said, the Soviets viewed this approach as ‘unacceptable’ and a violation of the Helsinki accords and also of agreements made in the current year. Finally, referring to his speech to the Central Committee on 9 December, Gorbachev highlighted the GDR’s Warsaw Pact membership and East Berlin’s status as a ‘strategic ally’ of the USSR, and he asserted that the Soviet Union would do anything to ‘neutralise’ all interference in East German affairs.[144]

Having heard much of this already via Genscher, Kohl was not seriously put out. What the letter seemed to show, he felt, was that Gorbachev was under the spell of Hans Modrow’s visit to Moscow on 4–5 December. Having not himself visited East Germany since the 7 October celebrations, the Soviet leader had no first-hand feeling of the situation or the popular mood. Taking his cue from Modrow – with his talk of reformed communism, continued East German independence, and a treaty community with the FRG – perhaps the Soviet leader was anxious to demonstrate his commitment to the GDR. That, at any rate, was the most positive reading of Gorbachev’s letter. A more pessimistic take was to focus on the Kremlin leadership’s rejection of the ‘tempo and finality’ of the German–German march toward unity and Gorbachev’s evident concern for ‘the geopolitical and strategic repercussions of this process for the Soviet Union itself’.[145]

The battle of the letters strengthened Kohl’s determination to exploit the window of opportunity before Christmas – to take the measure of Modrow and, at last, to immerse himself in East Germany’s revolution. Ironically, the West German chancellor had since the fall of the Wall travelled to West Berlin, Poland, France and most recently Hungary – but not to the GDR itself. This omission was finally rectified on the morning of 19 December when Kohl, Teltschik and a small entourage from the Chancellery landed in Dresden. Foreign Minister Genscher was not on board.

Kohl was a tactile politician, with keen antennae for public moods. He may have talked with passion about German unity to the Bundestag in Bonn but – as he admitted in his memoirs – it was when he encountered the cheering crowd at Dresden airport on that icy Tuesday morning that he really got the point. ‘There were thousands of people waiting amid a sea of black, red, and gold flags,’ Kohl recalled. ‘It suddenly became clear to me: this regime is finished. Unification is coming!’ As they descended the stairs onto the tarmac, there was another telltale sign: an ashen-faced Modrow gazing up at them with a ‘strained’ expression. Kohl turned round and murmured: ‘That’s it. It’s in the bag.’[146]

The leaders of the two Germanies sat next to each other in the car as they were driven at a snail’s pace into the city. They made small talk about their upbringing: Modrow, unmoving and self-conscious, went on about his working-class background and how he had risen from being a trained locksmith to completing an economics degree at the Humboldt University in Berlin. But Kohl was not really listening. His eyes were on the crowd lining the streets. He could barely believe what he saw. Nor could Teltschik, who captured the scenes in his diary: ‘whole workforces had come out of their factories – still wearing their blue overalls, women, children, entire school classes, amazingly many young people. They were clapping, waving big white cloths, laughing, thoroughly enjoying themselves. Some were simply standing there, crying. Joy, hope, expectation radiated from their faces – but also worry, uncertainty, doubt.’ In front of the Hotel Bellevue, where the formal talks were to take place, thousands more young people had congregated shouting ‘Helmut! Helmut!’ Some held banners proclaiming ‘Keine Gewalt’ (‘No violence’).[147]

Kohl and his aides felt exhilarated. During a brief pit stop in the hotel everyone had to unburden their feelings. They knew it was a ‘great day’, a ‘historical day’, an ‘experience that cannot be repeated’. After all that, the formal meetings were something of an anticlimax. The East German premier – stressed out, eyes down – went through his party piece about the need for economic aid and the reality of two German states – none of which particularly moved Kohl. When Modrow proposed that the Germanies first create a ‘community of treaties’ and then talk about what to do next ‘in about one or two years’, Kohl was incredulous. Demanding a frank and realistic talk about cooperation, he told Modrow there was no way he was coming up with DM 15 billion, nor would he allow any money, of whatever sum, to be designated by the historically loaded term ‘Lastenausgleich’ (‘compensation’).

By the end of the forty-five minutes a shaken Modrow realised that he had to operate on Kohl’s terms. That meant dropping his demand that the Joint Declaration they were going to sign should refer to a ‘treaty community originated by two sovereign states’. The chancellor totally rejected the language of ‘two states’ because that risked cementing the status quo and propping up the mere shell of an East German state. Instead, he focused on the German people and their exercise of the right to self-determination. By now Kohl was quite clear in his mind about what East Germans wanted: a single, unified Deutschland.[148]

Who’s boss? Kohl with Modrow in Dresden

After a rather stiff lunch and a press conference with journalists, the chancellor walked to the ruins of the Frauenkirche – destroyed in the Allied firebombing in 1945. In his memoirs Kohl claimed he had spoken to the crowd spontaneously, but in fact a speech had been prepared very carefully with Teltschik the night before. Amid the blackened stones of the eighteenth-century church – which had become a ‘memorial against war’ and a prime site in 1989 for anti-regime protests – Kohl climbed on a temporary wooden podium in the darkening winter evening. He looked out at a crowd of some 10,000. Many were waving banners and placards proclaiming such slogans as ‘Kohl, Kanzler der Deutschen’ (‘Kohl, Chancellor of the Germans’), ‘Wir sind ein Volk’ (‘We are one people’) and ‘Einheit jetzt’ (‘Unity now’).[149] But, presumably, blending into the mass of people were operatives of the Stasi and the Soviet security services – maybe even the KGB’s special agent in Dresden, Vladimir Putin.

His throat tight with emotion, the chancellor began slowly, feeling the weight of expectation. He conveyed warm regards to the people of Dresden from their fellow citizens in the Federal Republic. Exultant cheers. He gestured to show he had more to say. It got very quiet. Kohl then talked about peace, self-determination and free elections. He said a bit about his meeting with Modrow and talked of future economic cooperation and the development of confederative structures, and then moved to his climax. ‘Let me also say on this square, which is so rich in history, that my goal – should the historical hour permit it – remains the unity of our nation.’ Thunderous applause. ‘And, dear friends, I know that we can achieve this goal and that the hour will come when we will work together towards it, provided that we do it with reason and sound judgement and a sense for what is possible.’

Trying to calm the surging emotions, Kohl proceeded to speak matter-of-factly about the long and difficult path to this common future, echoing lines he had used in West Berlin the day after the fall of the Wall. ‘We, the Germans, do not live alone in Europe and in the world. One look at a map will show that everything that changes here will have an effect on all of our neighbours, those in the East and those in the West … The house of Germany, our house, must be built under a European roof. That must be the goal of our policies.’ He concluded: ‘Christmas is the festival of the family and friends. Particularly now, in these days, we are beginning to see ourselves again as a German family … From here in Dresden, I send my greetings to all our compatriots in the GDR and the Federal Republic of Germany … God bless our German fatherland!’

By the time Kohl ended, the people felt serene – mesmerised by the moment. No one made any move to leave the square. Then an elderly woman climbed onto the podium, embraced him and, starting to cry, said quietly: ‘We all thank you!’[150]

That night and next morning Kohl talked with Protestant and Catholic clergy from the GDR and leaders of the newly formed opposition parties.[151] All his meetings in Dresden simply proved to Kohl that the GDR elites were in denial about the desires of the broader public. The crowds in Dresden did not want a modernised GDR standing alone, as touted by the opposition, or an update of the old regime, led by Modrow and the renamed communists (PDS) in some kind of confederation with the FRG. Twenty-four hours amid the people of Dresden convinced the West German chancellor that his Ten-Point Plan was already becoming out of date. In what was now a race against time, those ‘new confederative structures’ he had been advocating were too ponderous and would take too long. The chancellor no longer had any inclination to support the Modrow government – clearly a flimsy, transitional operation that lacked any kind of democratic legitimacy and was merely trying to save a sinking ship from going under fast.[152]

Kohl could suddenly see a window of opportunity opening up in the midst of crisis. The cheers of the East German crowds spurred him on and served as the justification for dramatic action. As would-be driver of the unification train, he was now ready to move the acceleration lever up several notches. And he was also energised by the overwhelmingly positive reception in the media for his Dresden visit – both at home and abroad. The common theme next day was that a West German chancellor had laid the foundation for unification, and had done so on East German soil.[153]

Dresden was the beginning of a veritable sea change in public perceptions of Kohl. He had bonded with the people. He had addressed the East Germans repeatedly as ‘dear friends’. He had clearly relished being bathed in the adulation of the masses. The chants of ‘Helmut! Helmut!’ revealed the familiarity East Germans had suddenly come to feel for the West German leader. With all this shown live on TV in both Germanies, the chancellor and this mood of exuberant patriotism flooded into German living rooms from Berlin to Cologne, from Rostock to Munich.[154]

There were, of course, similar cheers for Willy Brandt at an SDP rally in the GDR city of Magdeburg on the same day. Hans-Dietrich Genscher was also greeted enthusiastically when he returned to East Germany to speak in his home town, Halle, and in Leipzig on 17 December.[155] But Kohl in Dresden outshone both of them by miles. Rarely had the chancellor – often the butt of ridicule as a clumsy provincial – experienced such an ecstatic reaction in his own West Germany. With national elections in the FRG now less than a year away and German unity looming as the dominant issue, Dresden was the best public-relations coup that the chancellor could have dreamed of.

Nor was there much international competition. On 19 December, the same day Kohl spoke in Dresden, Eduard Shevardnadze became the first Soviet foreign minister to enter the precincts of NATO[156] – another symbolic occasion in the endgame of the Cold War. On the 20th François Mitterrand became the first leader of the Western allies to pay an official state visit to the East German capital – another bridging moment across the crumbling Wall.[157] But both of these were almost noises off compared with Kohl’s big bang. What’s more, these initiatives were striking mainly by reference to the past, whereas the chancellor was looking to the future and everyone now knew it.[158]

What made that point transparently clear was the brief instant on 22 December – a rainy Friday afternoon just before the Christmas holiday – when Kohl and Modrow formally opened crossing points at the Brandenburg Gate. Watching the people celebrating the unity of their city, Kohl exclaimed: ‘This is one of the happiest hours of my life.’ For the chancellor at the end of that momentous year – less than a month after his Ten Point speech – Dresden and Berlin were indeed memories to savour.[159]

*

The end of 1989 was not happy for everyone, of course. As the Western world ate its Christmas dinner, TV screens were full of the final moments of Nicolae and Elena Ceaușescu. The absolute ruler of Romania for twenty-four years and his wife were executed by soldiers of the army that, until just a few days before, he had commanded.

Romania was the last country in the Soviet bloc to experience revolutionary change. And it was the only one to suffer large-scale violence in 1989: according to official figures 1,104 people were killed and 3,352 injured.[160] Here alone tanks rolled, as in China, and firing squads took their revenge. This reflected the nature of Ceaușescu’s highly personal and arbitrary dictatorship – the most gruesome in Eastern Europe. Having gone off on his own from Moscow since the mid-1960s, Ceaușescu had also stood apart from Gorbachev’s reformist agenda and peaceful approach to change.

So why, in this repressive police state, had rebellion broken out? Unlike the rest of the bloc, Ceaușescu had managed to pay off almost all of Romania’s foreign debts – but at huge cost to his people: cutting domestic consumption so brutally that shops were left with empty shelves, homes had no heat and electricity was rationed to a few hours a day. Meanwhile, Nicolae and Elena lived in grotesque pomp.

Despite such appalling repression, their fall was triggered not by social protest but by ethnic tensions. Romania had a substantial Hungarian minority, some 2 million out of a population of 23 million, who were treated as second-class citizens. The flashpoint was the western town of Timişoara where the local pastor and human-rights activist László To˝kés was to be evicted. Over the weekend of 17–18 December some 10,000 people demonstrated in his support, shouting ‘Freedom’, ‘Romanians rise up’, ‘Down with Ceaușescu!’ The regime’s security forces (the Securitate) and army units responded with water cannons, tear gas and gunfire. Sixty unarmed civilians were killed.[161]

Protest now spread through the country as people took to the streets, emboldened by the examples of Poland, Hungary and East Germany. The regime hit back and there were lurid reports of perhaps 2,000 deaths. On 19 December, the day Kohl was in Dresden, Washington and Moscow independently condemned the ‘brutal violence’.[162]

In Bucharest, Ceaușescu, totally out of touch with reality, sought to quell the chaos through a big address to a mass crowd on 21 December, which was also relayed to his country and the world on television. But his show of defiance was hollow. On the balcony of the presidential palace, the great dictator, now seventy-one, looked old, frail, perplexed, rattled – indeed suddenly fallible. Sensing this, the crowd interrupted his halting speech with catcalls, boos and whistles – at one point silencing him for three minutes. The spell had clearly been broken. As soldiers and even some of the Securitate men fraternised with the protestors in the streets, the regime began to implode. Next morning the Ceaușescus were whisked away from the palace roof by helicopter, but they were soon caught, tried by a kangaroo court and shot – or rather, mown down in a fusillade of more than a hundred bullets. Their blood-soaked bodies were then displayed to the eager cameramen.[163]

But Romania was 1989’s exception. Everywhere else, regime change had occurred in a remarkably peaceful way. In neighbouring Bulgaria, Todor Zhivkov – who boasted thirty-five years in power, longer than anyone else in the bloc – had been toppled on 10 November. Yet the world hardly seemed to notice because the media was mesmerised by the fall of the Wall the night before. In any case, this was simply a palace coup: Zhivkov was replaced by his foreign minister Petar Mladenov. It was only gradually that people power made itself felt. The first street demonstrations in the capital, Sofia, began more than a week later on 18 November, with demands for democracy and free elections. On 7 December, the disparate opposition groups congealed as the so-called Union of Democratic Forces. Under pressure, the authorities decided to make further concessions: Mladenov announced on the 11th that the Communist Party would abandon its monopoly on power and multiparty elections would be held the following spring. Yet the sudden ousting of Zhivkov did not produce any fundamental transfer of power to the people, as in Poland, or a radical reform programme, as in Hungary. Hence the preferred Bulgarian term for 1989: ‘The Change’ (promianata). In a few weeks, the veritable dinosaur of the Warsaw Pact had been quietly consigned to history.[164]

Most emblematic of the national revolutions of 1989 was Czechoslovakia. The Czechs witnessed the GDR’s collapse first-hand, as the candy-coloured Trabis chugged through their countryside and the refugees flooded into Prague.

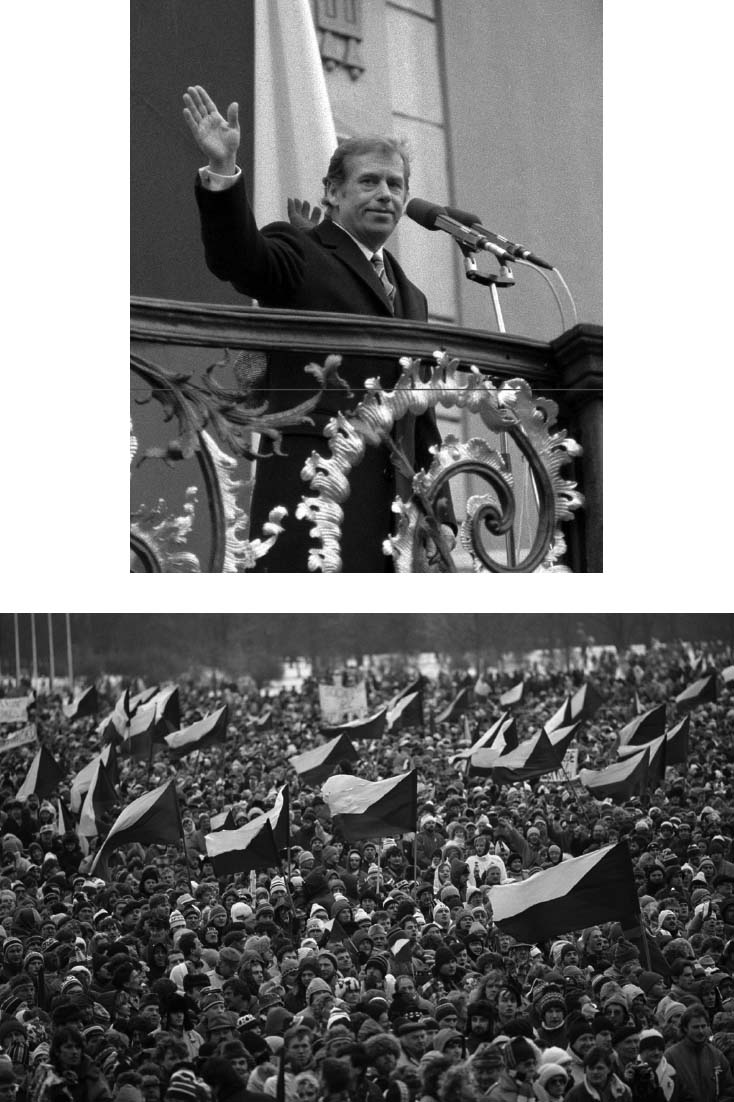

Driving to freedom: Trabis in Czechoslovakia

But their own communist elite had an uncompromisingly hardline reputation and so change came late to Czechoslovakia. Indeed, Miloš Jakeš, the party leader, had rejected any moves for reform from above, as in Hungary and Poland. Yet there was context. Memories of 1968 – only two decades earlier – were still vivid and painful. But then they were galvanised by the scenes at the Berlin Wall on 9–10 November. A week later, on the 17th, the commemoration for a Czech student murdered by the Nazis fifty years before, rapidly escalated into a demonstration against the regime which the police broke up with force. This was the spark. Every day for the next week, the student protests mushroomed – drawing in intellectuals, dissidents and workers and spreading across the country. By the 19th the opposition groups in Prague had formed a ‘Civic Forum’ (in Bratislava, the capital of Slovakia, the movement was called ‘Public against Violence’) and by the 24th they were in talks with the communist government – which was now dominated by moderates after the old guard around Jakeš had resigned. The two key opposition figures – each in his own way deeply symbolic – were the writer Václav Havel, recently released from imprisonment for dissident activities as a key member of the Charter 77 organisation – and the Slovak Alexander Dubček, leader of the Prague Spring in 1968. The formal round-table negotiations took place on 8 and 9 December. The following day President Gustáv Husák appointed the first largely non-communis government in Czechoslovakia since 1948, and then stepped down.[165]

The pace of change had been breathtaking. On the evening of 23 November Timothy Garton Ash – who had witnessed Poland’s upheavals in June and then the start of Czechoslovakia’s revolution – was chatting to Havel over a beer in the basement of Havel’s favourite pub. The British journalist joked: ‘In Poland it took ten years, in Hungary ten months, in East Germany ten weeks; perhaps in Czechoslovakia it will take ten days!’ Havel grasped his hand, smiling that famous winning smile, summoned a video team who happened to be drinking in the corner, and asked Garton Ash to say it again, on camera. ‘It would be fabulous, if it could be so,’ sighed Havel.[166] His scepticism was not unwarranted. Admittedly the revolution took twenty-four days not ten, but on 29 December Václav Havel was elected president of Czechoslovakia by the Federal Assembly in the hallowed halls of Prague Castle.

The playwright becomes president: Václav Havel and the Velvet Revolution in Prague