Полная версия

Post Wall, Post Square: Rebuilding the World after 1989

As regards the international situation, however, standing on the Cold War front line in the heart of Europe, the Soviet leader was defiant. In his speech during the gala dinner on the 6th, he rebutted accusations that Moscow bore sole responsibility for the continent’s post-war division and he took issue with West Germany for seizing on his reforms to ‘reanimate’ dreams of a German Reich ‘within the boundaries of 1937’. He also specifically rejected demands that Moscow dismantle the Berlin Wall – a call made by Reagan in 1987 and again by Bush in 1989. ‘We are constantly called on to liquidate this or that division,’ Gorbachev complained. ‘We often have to hear, “Let the USSR get rid of the Berlin Wall, then we’ll believe in its peaceful intentions.”’ He was adamant that ‘we don’t idealise the order that has settled on Europe. But the fact is that until now the recognition of the post-war reality has insured peace on the continent. Every time the West has tried to reshape the post-war map of Europe it has meant a worsening of the international situation.’ Gorbachev wanted his socialist comrades to embrace renewal, but he had no intention of dismantling the Warsaw Pact or abruptly dissolving the Cold War borders that had given stability to the continent for the last forty years.[179]

And so, each in his own way, these two communist leaders were hanging on to the past. Gorbachev adhered to existing geopolitical realities, despite the cracks opening up in the Iron Curtain. Honecker clung to the illusion that East Germany remained a socialist nation, united by adherence to the doctrines of the party.

The intransigence of the GDR regime during the celebrations, and the growing social unrest of recent weeks, made for a potentially explosive mix. Within less than two weeks Honecker had been ousted. And only a month after the GDR’s fortieth-birthday party, on 9 November, the Berlin Wall fell without a fight. The Wall had been the prime symbol of the Cold War, the barrier that contained the East German population and the structure that held the whole bloc together. The party of 7 October proved to be a theatre of illusions. Yet there was nothing inevitable about what came next.

Chapter 3

Reuniting Germany, Dissolving Eastern Europe

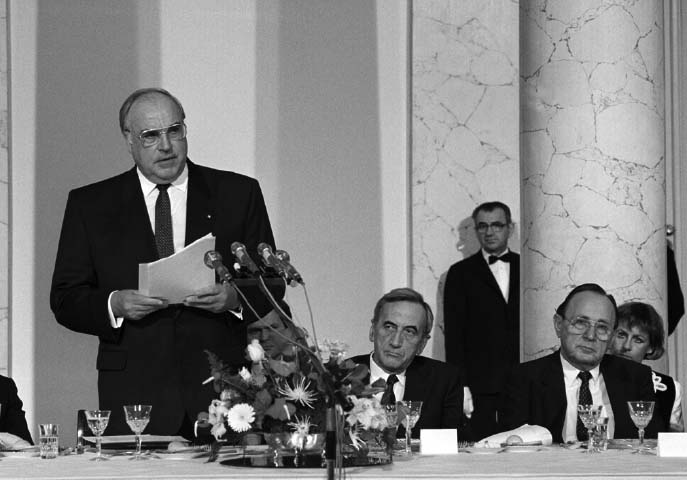

The 9th of November 1989. Helmut Kohl was beside himself. Here he was, sitting at a grand banquet in the Radziwill Palace in Warsaw with the new leaders of Poland – Mazowiecki, Jaruzelski and Wałęsa – in a wonderfully festive atmosphere, together with a delegation of seventy, including Foreign Minister Hans-Dietrich Genscher and six other ministers of his Cabinet. But all around him people were murmuring ‘Die Mauer ist gefallen!’ (‘The Wall has fallen!’). Throughout that Thursday evening, as the chancellor tried to make polite chit-chat with his hosts, he kept being interrupted – receiving updates on little slips of paper and being called out to take phone calls from Bonn. All the while Kohl was desperately trying to think.[1] He was in the wrong place at the right time – the most dramatic moment of his chancellorship, perhaps of his whole life. What should he do?

Moment of reconciliation: Kohl, Mazowiecki and Genscher in Warsaw

Kohl’s mood had been very different when the dinner started. His five-day visit, in the planning for months, was intended as a milestone in West Germany’s relations with one of its most sensitive neighbours. History hung heavy in 1989. This was fifty years after Hitler’s brutal invasion of Poland, beginning a war that led to the extermination of 6 million Polish citizens (half of them Jewish), the obliteration of the city of Warsaw after the abortive rising of 1944, and the absorption of Poland into the Soviet bloc in 1945. Germany had a lot to answer for, and the process of reconciliation by Bonn had been long and painful. It had been an SPD chancellor, Willy Brandt, who made the first and more dramatic move in December 1970, dropping to his knees in silent remorse at the memorial to the Warsaw Ghetto. Kohl’s trip was the first time a Christian Democrat chancellor had visited Poland. But he was not simply catching up with his political rivals and trying to redress the past; he also wanted to make a statement about the future, about the Federal Republic’s commitment to Poland’s resurrection as a free country in its post-communist incarnation. So the German chancellor had been delighted to sit down at the banquet that evening. Delighted, that is, until he got the news from Berlin.[2]

As soon as the dinner was over, the Germans held a crisis meeting over coffee. The situation was extremely delicate. The Polish leadership wanted to stop Kohl from going to Berlin, warning that this would be taken as a blatant snub. Horst Teltschik, the chancellor’s top foreign-policy adviser, was also hesitant. ‘Too much has been invested in this trip to Warsaw,’ he warned, ‘too much hangs on it for the future of German–Polish relations.’ Among the events on Kohl’s itinerary were a visit to Auschwitz – as an act of penitence for the Holocaust, preceded only once, by Chancellor Helmut Schmidt (also SPD) in 1977 – and a bilingual Catholic Mass in Lower Silesia shared with Mazowiecki, set up as an act of reconciliation with the Poles. The mass was to be held in a place – the Kreisau estate of Graf von Moltke, one of the July 1944 Christian conservative plotters against Hitler – that symbolised a ‘better Germany in the darkest part of our history’, as the chancellor later put it. Kohl giving the kiss of peace to Mazowiecki linked up with his other iconic act of reconciliation: holding hands with Mitterrand at Verdun in 1984. But this gesture in Silesia was also intended to speak, at home, to the Vertriebene – the ever-prickly members on the right of his own party who had been expelled from the eastern German territories when these were absorbed into the new Poland (and the Soviet Union) after 1945.[3]

Upon leaving the Radziwill Palace, Kohl rushed to the city’s Marriott Hotel, where the West German press corps was staying, to answer their questions. And he remained for several hours because only in a Western hotel was it possible to see the news on German TV and to access a sufficient number of international phone lines. At midnight, when he spoke once more to the Chancellery, staff there confirmed that the crossing points in Berlin were opened. They also conveyed a sense of the massive flows of people and the joyous atmosphere in the once-divided city. Putting down the phone, the chancellor – pumped up with adrenalin – told the journalists that ‘world history is being written … the wheel of history is spinning faster’.[4]

Kohl decided to return to Bonn as soon as diplomatically feasible. ‘We cannot abort the trip,’ he observed, ‘but an interruption is possible.’ Next morning, 10 November, he placated his Polish hosts with a Brandt-style visit to the Warsaw Ghetto and a promise that he would be back within twenty-four hours. By the time he left Poland together with Genscher and a handful of journalists at 2.30 p.m., his destination had changed. While at the Ghetto Memorial, Kohl had received more disturbing news. Walter Momper, the SPD mayor of West Berlin, was organising a major press event, featuring his fellow socialist and former chancellor Willy Brandt, on the steps of the city hall (Schöneberger Rathaus) at 4.30 p.m. that very day. Brandt – the mayor of West Berlin when the Wall went up in August 1961 and then the celebrated chancellor of Ostpolitik – was now going to hog the limelight as the Wall came down. With barely a year to go before the next Federal elections, Kohl could not afford to be upstaged – especially when an earlier CDU chancellor, Konrad Adenauer, had been conspicuously absent from Berlin during those fateful days in 1961 when the eastern half of the city was walled in.

It was all very well to want to go to Berlin. But getting there in November 1989 was no simple business. West German aircraft were not permitted to fly across GDR territory or land in West Berlin because of the Allied four-power rights – another legacy of Hitler’s war. So Kohl and Genscher flew circuitously through Swedish and Danish airspace to Hamburg before boarding a plane specially provided by the US Air Force for the flight to Berlin. Both men used the journey to frantically scribble their speeches. As much as they were partners, they were in the end also political rivals jockeying for position. After this humiliating diversion, they landed at Tempelhof, right in the centre of the city, just as the celebration at the Schöneberger Rathaus was about to begin. Sharing the spotlight with Brandt, they addressed a crowd of 20,000 and world media on the very steps from which, in 1963, President John F. Kennedy had declared ‘Ich bin ein Berliner.’[5]

That evening, three key figures of FRG politics each put his own spin on the momentous events of the last twenty-four hours. Brandt, in keeping with his Ostpolitik strategy of ‘small steps’, talked of the ‘moving together of the German states’, emphasising that ‘no one should act as if he knows in which concrete form the people in these two states will find a new relationship’. Genscher opened his address by emotionally recalling his roots in East Germany, from which he fled after the war: ‘My most hearty greetings go to the people of my homeland.’ He was much more emphatic than Brandt about the underlying fact of national unity. ‘What we are witnessing in the streets of Berlin in these hours is that forty years of division have not created two nations out of one. There is no capitalist and there is no socialist Germany, but only one German nation in unity and peace.’ But, as foreign minister, he was anxious to reassure Germany’s neighbours, not least the Poles. ‘No people on this earth, no people in Europe have to fear if the gates are opened now between East and West.’[6]

Chancellor Kohl spoke last. While the sea of Berlin lefties had cheered Brandt and Genscher, they had no patience with the bulky conservative Catholic politico from the Rhineland. Here party enmity, regional pride and explosive emotions combined; the spectators tried to drown out every word of Kohl’s speech with boos, catcalls and whistling. The chancellor felt his anger rise at the behaviour of what he called contemptuously the ‘leftist plebs’ (linker Pöbel). Suppressing his fury, he ploughed on doggedly. Mindful of the upcoming election, Brandt’s iconic place in the history of Deutschlandpolitik and the way that Genscher had grabbed his moment on the balcony in Prague, Kohl ignored the crowd in front of him and spoke to millions of TV viewers, especially in the GDR. He sought to present himself as the man who was really in control, the true leader and statesman. He urged East Germans to stay put and to stay calm. He reassured them: ‘We’re on your side, we are and remain one nation. We belong together.’ And the chancellor made a particular point of thanking ‘our friends’ the Western allies for their enduring support and ended by playing the European card: ‘Long live a free German fatherland! Long live a united Europe!’[7]

For many – at home and abroad – Kohl’s expression of nationalism went too far. An ominous phone message from Gorbachev was received during the rally. He warned that the Bonn government’s declarations could fan ‘emotions and passions’ and went on to stress the existence of two sovereign German states. Whoever denied these realities had only one aim – that of destabilising the GDR. He had also heard rumours that a furious German mob had plans to storm Soviet military facilities. ‘Is this true?’ he asked. Gorbachev urged Kohl to avoid any measures that ‘could create a chaotic situation with unpredictable consequences’.[8]

Gorbachev’s message summed up the turmoil of the past couple of days, and it also did not appear to bode well for the future. Kohl sent a reply assuring the Soviet leader that he need not worry: the atmosphere in Berlin was like a family feast and nobody was about to start a revolt against the USSR.[9] But, with a profound sense of risk in the air, these were fraught and uncertain times for the chancellor. Would his three Western allies react as negatively as Gorbachev? As soon as he got back to his Bonn office later that evening, despite his exhaustion, he tried to arrange phone calls with Thatcher, Bush and Mitterrand.

He rang Thatcher first, at 10 p.m., because he thought that conversation would be ‘the most difficult’.[10] On the face of it, however, it went well. The prime minister, who had been watching events on television, said that the scenes in Berlin were ‘some of the most historic which she had ever seen’. She stressed the need to build a true democracy in East Germany and the two of them agreed to keep in close touch: Thatcher even suggested coming over for a half-day meeting before the upcoming European Council in Strasbourg early in December. Throughout the conversation, there was no mention of the word ‘unity’, but the chancellor clearly sensed that she felt ‘unease’ at the implications of the situation.[11]

He was able to extricate himself in less than half an hour, ready for what promised to be a more agreeable chat at 10.30 p.m. with George Bush. Kohl started with a survey of his trip to Warsaw and the economic predicament of Poland, but the president wasn’t interested. Cutting in, Bush said he wanted to hear all about the GDR. Kohl admitted the scale of the refugee problem and expressed scepticism about Krenz as a reformer. He also let off steam about those ‘leftist plebs’ who had tried to spoil his speech. But his assessment, overall, was very positive: the general mood in Berlin was ‘incredible’ and ‘optimistic’ – like ‘witnessing an enormous fair’ – and he told Bush that ‘without the US this day would not have been possible’. The chancellor could not stress enough: ‘This is a dramatic thing; an historic hour.’ At the end Bush was extremely enthusiastic: ‘Take care, good luck,’ he told Kohl. ‘I’m proud of the way you’re handling an extraordinarily difficult problem.’ But he also remarked ‘my meeting with Gorbachev in early December has become even more important’. Bush was right, the long-awaited tête-à-tête between him and the Soviet leader – only recently scheduled to take place in Malta on 2–3 December – could now not come soon enough.[12]

It was not possible to talk with Mitterrand that night. When they did speak at 9.15 the next morning Kohl took the same line but with an appropriately different spin. Not forgetting that 1989 was the bicentenary of the start of the French Revolution, the chancellor likened the mood on the Kurfürstendamm (West Berlin’s main shopping street) to the Champs-Elysées on Bastille Day. But, he added, the process in Germany was ‘not revolutionary but evolutionary’. Responding in similar vein, the French president hailed events in Berlin as ‘a great historical moment … the hour of the people’. And, he continued, ‘we now have the chance that this movement would flow into the development of Europe’. All very positive, of course, but perhaps also a reminder of traditional French concerns to see a strong Germany firmly anchored in the European integration project. Kohl had no problem with this and he was happy that both of them emphasised the strength of the Franco-German friendship.[13]

After talking to Mitterrand, Kohl took a call from Krenz – who had been pressing for a conversation. The two spoke for nine minutes – politely but insistently on both sides. Krenz was emphatic that ‘currently reunification was not on the political agenda’. Kohl said that their views were fundamentally different because his position was rooted in the FRG’s Basic Law of 1949, which affirmed the principle of German unity. But, he added, this was not the topic that should concern them both at the moment. Rather, he was interested in ‘getting to decent relations between ourselves’. He looked forward to coming to East Germany for an early personal meeting with the new leadership. Yet, he wanted to do so ‘outside East Berlin’ – the familiar FRG concern to avoid any hint of recognition of the GDR’s putative capital.[14]

The last of Kohl’s big calls – and the most sensitive of all – was with Gorbachev, before lunch on 11 November. Kohl set out some of the grave economic and social problems now facing the GDR, but stressed the positive mood in Berlin. Gorbachev was less testy than in his initial message to Kohl the previous day and expressed his confidence in the chancellor’s ‘political influence’. These were, he said, ‘historical changes in the direction of new relations and a new world’. But he emphasised the need above all for ‘stability’. Kohl firmly agreed and, according to Teltschik, ended the conversation looking visibly relieved. ‘De Bärn is g’schält’ (‘The pear has been peeled’) he told his aide in a thick Palatinate accent with a broad smile: it was clear that Gorbachev would not meddle in internal East German affairs, as the Kremlin had done in June 1953.[15]

Kohl could now feel reassured about his allies and the Russians, yet these were not his only worries. As he got off the phone he must have reflected on his own Deutschlandpolitik – its future direction and the responsibilities that now weighed heavily on him. All the more so, given what he had learned in Cabinet that morning about just how unstable the situation really was.

So far that year, according to the Interior Ministry, 243,000 East Germans had arrived in West Germany, as well as 300,000 ethnic Germans (Aussiedler) who could claim FRG citizenship: in other words, well over half a million immigrants in ten months. And this was before the fall of the Wall. The economic costs were also escalating. According to the Finance Ministry, DM 500 million had to be added to the budget in 1990 just to provide emergency shelters for the recent influx of GDR refugees. And an additional DM 10 billion a year for the next ten years might be required to build permanent housing and provide social benefits and unemployment payments. Moreover, the FRG was already subsidising the GDR economy to the tune of several billion a year. And far more would clearly be needed if the GDR were to be propped up sufficiently to stem the haemorrhage of people. But for how long could it be sustained? And what would happen if Germany unified? Revolution was certainly turning the East upside down, but life for West Germans was evidently changing as well – and not all those changes were welcome.[16]

Even if, in the short term, such spending on the GDR and on the migrants was economically feasible, any talk of raising taxes to cover the costs was politically impossible for Kohl and his coalition partners in an election year. The recent rise in the FRG of the Republikaner (the radical right’s new party) reflected growing resentment at the immigrant crisis and dismay at the financial burden to be carried by West German citizens.[17]

Although Kohl had talked about ‘stability’ to Gorbachev and to his Western allies, as he flew back to Warsaw on the afternoon of 11 November to pick up the threads of his Polish visit, he must have seen how difficult it would be to keep the GDR functioning. But, of course, he had no real desire to do so in the longer run. The ‘stability’ he was now beginning to contemplate was how to facilitate a peaceful and consensual transition to a unified German state – a project that had been inconceivable just two days before.[18]

*

How had this Rubicon been reached, only five weeks after the grand celebrations to mark the fortieth anniversary of the East German state?

In reality the big party on 7 October was a facade, to paper over the huge and growing cracks in the communist state. As soon as Gorbachev left East Berlin for Moscow, demonstrations erupted across the city and elsewhere in the GDR and the authorities now cracked down hard. The 7th was the day of what had become a monthly protest against the May election fraud. Nevertheless, while those who had fled the country amounted to tens of thousands, the number of dissidents and those openly antagonistic to the regime was still relatively small, especially outside the big cities of Dresden, Leipzig and East Berlin. Protests and demonstrations were quite contained, involving no more than several hundred people. Formal opposition groups had only just been created since the opening of the Austro-Hungarian border: by the beginning of October some 10,000 people belonged to Neues Forum as well as Demokratie Jetzt, Demokratischer Aufbruch, SDP (SozialDemokratische Partei in der DDR) and Vereinigte Linke. These smaller groupings were mostly associated with Neues Forum. Millions of GDR citizens remained passive and hundreds of thousands were still willing to defend the state.[19]

The atmosphere in those days was tense and uncertain – the rumour mill was in overdrive about what might happen next. At the top, Erich Honecker envisaged a ‘Chinese solution’ to counter the mounting protests over the anniversary weekend (6–9 October),[20] prefigured in East Berlin when Stasi boss Erich Mielke jumped out of his bulletproof limo on the evening of 7 October screaming to police ‘Haut sie doch zusammen, die Schweine!’ (‘Club those pigs into submission!’).[21] That night in and around Prenzlauer Berg near the Gethsemane church, police officers, plain-clothes security forces and volunteer militia attacked some 6,000 demonstrators who shouted ‘Freedom’, ‘No violence’ and ‘We want to stay’, as well as bystanders, with dogs and water cannons – beating and kicking peaceful citizens and throwing hundreds into jail. Women and girls were stripped naked; people were not allowed to use the toilets and told to piss or shit in their pants. Those who asked where they would be taken were told: ‘Auf eine Müllkippe’ (‘To the landfill’).[22]

Unlike similar scenes in other East German cities, where foreign journalists were banned, the images from East Berlin that weekend soon went around the world. And when those arrested were released and talked to the press, what they told the cameras about merciless brutality by the riot police and abuse at the hands of the Stasi interrogators was both really shocking and also entirely believable. Because many of them were simply ordinary citizens, some even SED members, not militant protestors or hardcore dissidents.[23]

Matters came to a head on Monday 9 October in Leipzig, which had been the epicentre of people-protest for the past few weeks. In fact the Monday night demo there had become a weekly feature since the first gathering by a few hundred in early September, spilling out spontaneously – as numbers grew exponentially – from the evening prayers for peace (Friedensgebet) in the Nikolaikirche in the city centre to a big rally along the inner ring road. On the night of 25 September, the fourth such occasion, 5,000 people had come together; a week later there were already 15,000, calling for ‘Demokratie – jetzt oder nie’ (‘Democracy – now or never’), and ‘Freiheit, Gleichheit, Brüderlichkeit’ (‘Freedom, equality, fraternity’). On the march, they chanted defiantly ‘Wir bleiben hier’ (‘We stay here’), as opposed to the earlier ‘Wir wollen raus’ (‘We want out’), while demanding ‘Erich laß die Faxen sein, laß die Perestroika rein’ (‘Erich [Honecker] stop fooling around, let the perestroika in’). Each week, Leipzigers became more daring in their activities and more vehement in their demands.[24]

The 9th of October was expected to be the largest ever protest – facing off against the regime’s full display of force. With this in mind, the Leipzig opposition groups and churches had disseminated appeals for prudence and non-violence. The world-renowned conductor Kurt Masur of the Gewandhaus orchestra, together with two other local celebrities, enlisted the support of three leading SED functionaries of the city government, and issued a public call for peaceful action: ‘We all need free dialogue and exchanges of views about further development of socialism in our country.’ What’s more, they argued, dialogue should not only be conducted in Leipzig but also with the government in East Berlin. This so-called ‘Appeal of the Six’ was read aloud, as well as being broadcast via loudspeakers across the city during the evening church vigils.[25]