Полная версия

Island Stories: Britain and Its History in the Age of Brexit

The 1550s proved a critical turning point, defined by the accidents of gender and mortality. Henry died in 1547. His young son Edward VI was an ardent Protestant, eager to promote his faith, but he died – probably of tuberculosis – in 1553, aged 15. Anticipating his death, Edward tried to ensure a Protestant succession by willing the Crown to his cousin, Lady Jane Grey. But her reign lasted only nine days before Mary, Catherine of Aragon’s daughter, was installed on the throne. A staunch Catholic, committed to extirpating Protestantism, Mary married the heir to the Spanish throne, who became King Philip II in 1556. This placed England on the other side of Europe’s wars of religion. But then in 1558, Mary died aged 42, possibly from cancer of the uterus. She was succeeded by her half-sister Elizabeth – the daughter of Anne Boleyn, who was then 25. Given the fate of her siblings, few would have predicted at her accession that Elizabeth would reign for nearly 45 years. In 1562, for instance, she contracted smallpox and seemed close to death. Her fortuitous longevity proved to be of huge historical significance.

Elizabeth was a firm but cautious Protestant. Both those adjectives mattered: she secured the Reformation but did not allow religion to divide the country as happened in France. Equally important, in 1559–60 Scotland’s anti-Catholic nobles expelled the French and established a Protestant regime. What ensued has been described as ‘the greatest transformation in England’s foreign relations since the start of the Hundred Years’ War’ – making ‘an ally of England’s medieval enemies the Scots, and an enemy of its medieval allies the Burgundians’ whose possessions in the Netherlands had now passed to Philip of Spain.[14] What’s more, France and Spain finally made peace in 1559 after nearly seven decades of periodic conflict, freeing Philip to concentrate on his mission of rolling back the Reformation.

In 1567 the Duke of Parma began a ruthless Spanish campaign to suppress the Protestant-led rebellion in the Low Countries; in 1572 thousands of French Protestants were killed in what became known as the Saint Bartholomew’s Day Massacre. At home Elizabeth, pressed by her advisers, turned on recalcitrant Catholics as potential traitors; abroad she began to aid the Dutch revolt in the interests of national security. This escalating confrontation with Spain climaxed in Philip’s abortive invasion in July 1588 – which was defeated not so much by English naval prowess as by the fabled ‘Protestant wind’ that prevented the Spanish Armada from linking up with Parma’s army in Flanders and instead drove the sailing ships into the North Sea. A third of the original 130 vessels did not make it around Scotland and home to Spain.

From these years of fevered insecurity, when regime and religion both seemed to hang in the balance, there emerged a new national ideology. Rooted in providentialist interpretations of recent history, it depicted the English as a staunchly Protestant nation, blessed by God’s protection. An intellectual landmark was John Foxe’s Actes and Monuments of these Latter and Perillous Days, Touching Matters of the Church – popularly known Foxe’s Book of Martyrs because it was a collection of stories – some true, others little more than rumour – about Christian martyrs, mostly anti-Catholic. Foxe had started compiling his work in Latin, while exiled on the Continent during Mary’s reign. Returning to England in 1559, soon after Elizabeth acceded to the throne, he was quickly taken under the wing of her principal adviser, William Cecil, who put Foxe in touch with the printer John Day, persuaded him to publish in English and also helped finance what was a truly massive project – the biggest book printed in England to date. The first edition, which appeared in 1563, ran to 1,800 pages, lavishly illustrated with 60 woodcuts; the second, in 1570, filled 2,300 pages – more than two million words – in two volumes, with 150 illustrations. Over the course of Elizabeth’s reign five editions were published; four more followed during the seventeenth century; and abridged versions, in cheap instalments, were printed throughout the eighteenth century – carrying Foxe’s message to a new and much wider audience.[15]

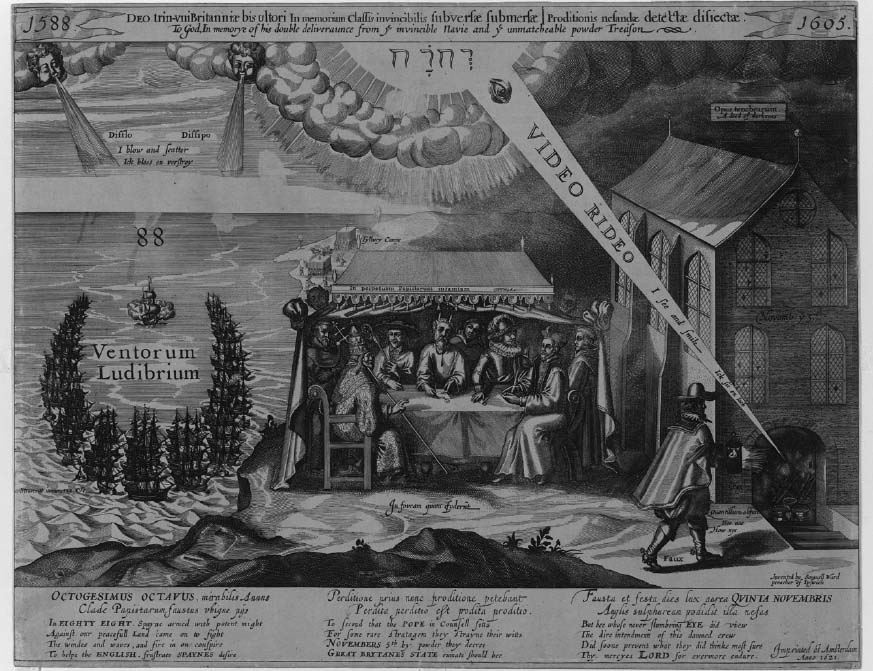

‘The Double Deliverance’: Samuel Ward’s print, published in Amsterdam in 1621 and widely distributed. In the centre the Pope and a Spanish grandee (King Philip II?), with advisers including the Devil, plot England’s destruction. Left: the Armada of 1588 is blown away by the wind from Heaven. Right: Guy Fawkes prepares his deadly plot but the all-seeing Jehovah smiles on his chosen people in England. [16]

This providentialist sense of the English as a Chosen People – like the Israelites of old – became enshrined in the national calendar. Particularly significant in English national memory was what preacher Samuel Ward called in 1621 the nation’s ‘double deliverance’ from ‘the invincible navie’ and ‘the unmatcheable powder treason’ – in other words, from the Armada of 1588 and the Catholic plot to blow up king and parliament in 1605. The failure of both were depicted as acts of divine intervention.

The Gunpowder Treason Plot became even more sacred to Protestant memory during the reign of the crypto-Catholic Charles I and the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. Charles’ attempt to impose an Anglican prayer book on the Scottish Presbyterian church provoked the so-called Bishops’ Wars of 1639–40. In an effort to put down the Scottish revolt, the King tried to raise an army of Irish Catholics, which deepened suspicions that he was a Papist. Finally obliged to call Parliament in London into session, after more than a decade, in order to obtain money for the Scottish war, Charles was confronted by a long list of civil and religious grievances from a legislature that voted itself into permanent session (the ‘Long Parliament’) until its demands were met. Deadlock turned into confrontation and then three English civil wars between 1642 and 1651, which were intertwined with the politico-religious struggles in Scotland and Ireland.

Charles was executed in 1649 and although his son regained the throne in the Restoration of 1660 as Charles II, he returned to a country permanently changed by the civil wars. England was now firmly established as a constitutional monarchy committed to a Protestant church. So much so that when Charles’ brother and successor, James II, turned to Catholicism, he was displaced in 1688 in favour of his Protestant daughter, Mary, and her Dutch Calvinist husband William of Orange. After Mary died in 1694, ‘King Billy’ reigned alone until his death in 1702. The year before, a parliament dominated by Tory squires passed the Act of Settlement, prohibiting a Catholic (or anyone married to a Catholic) from acceding to the throne. This was no ritual act of piety. In 1707, ensuring the Protestant succession throughout Britain was a major reason for the Anglo–Scottish Treaty of Union, which established a new constitutional entity, Great Britain. And in 1714, when Queen Anne (Mary’s younger sister) died without a living heir, Parliament passed over more than fifty individuals closer to her in blood yet Papist in faith. Instead they invited Georg Ludwig, Elector of Hanover – barely able to speak English but a staunch Lutheran – to be crowned King George I.[17] In other words, to preserve England as a constitutionally affirmed Protestant nation it was considered an acceptable price, both in 1688 and also 1714, to call in a continental monarch.

The Protestant succession also brought with it renewed engagement with the Continent. By the 1680s France, under Louis XIV, had replaced Spain as Europe’s predominant Catholic power. Autocratic and aggressive, Louis and his successors sought to expand through enforced dynastic marriages and overt military conquest – a project seen by many in Britain as portending a ‘universal monarchy’. The French directly supported the son and grandson of James II in their bids to put the Stuarts back on the throne through invasions in 1715 and 1745. This threat forced Britain into continental alliances in the wars of 1689–97, 1702–13 and 1743–8 – waged to restrain French power.

In any case, the Protestant succession meant that Britain was itself a continental monarchy. Except for the twelve years of Queen Anne (1702–14), ‘from 1688 to 1837 the holder of the British thrones was simultaneously ruler of significant continental European territories’ – the United Provinces under William III and the Electorate of Braunschweig-Lüneburg under the Hanoverian dynasty. Although generally known as Hanover after its capital city, the Electorate actually covered much of north-central Germany – from Brunswick to Bremen on the North Sea, and from Göttingen to the edge of Hamburg. George I and George II were rulers of two separated territories and – retaining deep German roots – they took their continental obligations seriously, spending at least one summer in three in Hanover, together with key ministers usually headed by the senior Secretary of State. This pattern was broken only in 1760 with the accession of George III – the first Hanoverian to be born in Britain and to speak English as his mother tongue. Indeed he never visited Hanover during his sixty-year reign.[18]

The Hanover connection and the experience of fighting continental wars gave the eighteenth-century British political elite a keen awareness of Europe as a whole, both geographically and politically. This also discouraged insular isolationism. In 1716 the Earl of Sunderland asserted that ‘the old Tory notion that England can subsist by itself whatever becomes of the rest of Europe’ had been ‘justly exploded since the revolution’ of 1688. In 1742 the MP John Perceval ridiculed the idea ‘that this country is an island entrenched within its own natural boundaries, that it may stand secure and unconcerned in all the storms of the rest of the world’. The politician Lord Carteret insisted in 1744 that ‘our own independence’ was closely linked to ‘the liberties of the continent’.[19] And setbacks against the French were often blamed on eighteenth-century equivalents of lack of willpower: luxury, selfishness, even an addiction to tea. ‘Were they the sons of tea-sippers’, asked the pamphleteer Jonas Hanway, ‘who won the fields of Cressy and Agincourt, or dyed the Danube’s streams with Gallic blood’ at Blenheim?[20]

It became an explicit theme of Whig political rhetoric during the first half of the eighteenth century that the ‘national interest’ required Britain to maintain a ‘balance of power’ on the Continent, through judicious alliances and selective intervention. Yet there were many who disagreed. One critic claimed in 1742 that the idea of it ‘being the Honour of England to hold the balance of Europe has been so ignorantly interpreted, so absurdly applied, and so perniciously put into practice, that it has cost this Nation more lives, and more money, than all the national Honour of that kind in the World is worth’.[21] The Tory politician and political philosopher Lord Bolingbroke offered an alternative strategy. ‘Great Britain is an island,’ he insisted. ‘The sea is our barrier, ships are our fortresses, and the mariners that trade and commerce alone can furnish are the garrisons to defend them.’ Bolingbroke did not totally rule out sending soldiers to the Continent. ‘Like other amphibious animals, we must come occasionally on shore,’ he admitted, ‘but the water is more properly our element, and in it, like them, as we find our greatest strength, so we exert our greatest force.’[22]

Emerging here was what would prove to be a lasting tension in debates about British foreign policy between a ‘continental’ and a ‘maritime’ strategy. The latter became more plausible after 1760 under a monarch who did not share his predecessors’ orientation towards Hanover, both personally and politically. What’s more, Britain’s trade had now shifted away from northwest Europe to the Mediterranean, East Indies, Caribbean and the American colonies, in an increasingly profitable nexus of goods, commodities and people-trafficking. The major wars against France in the second part of the ‘long eighteenth century’ – 1756–63, 1778–83, 1793–1802 and climacterically 1803–15 – were struggles for global empire, especially in North America and the Indian sub-continent. Indeed Britain was now, to quote historian Peter Marshall, ‘a nation defined by Empire’.[23]

Yet also still defined by its relations with the rest of Europe: every one of these wars entailed threats to the security of the British homeland, above all the menace of invasion by Napoleon in 1803–5. But except for the crisis years of 1812–15, Britain did not deploy large armies on the continent – using instead its commercial wealth and stable national debt to employ foreign mercenaries as its contribution to continental alliances. In 1760, for instance, at the height of the Seven Years’ War, there were 187,000 soldiers in Britain’s pay yet the contingent of British and Irish troops sent to Germany numbered only 20,000.[24] In the seven wars against France from 1688 to 1815, the British were diplomatically isolated just once, when Spain and the Dutch joined France in 1779–80. As a result, Britain lost control of the seas and, with this, its American colonies.

These conflicts had a profound effect on national identity. ‘Great Britain’ – the union of England and Wales with Scotland in 1707 – was an invented nation, forged and hardened through these conflicts. ‘A powerful and persistent threatening France became the haunting embodiment of that Catholic Other which Britons had been taught to fear since the Reformation,’ historian Linda Colley has observed. ‘Confronting it encouraged them to bury their internal differences in the struggle for survival, victory and booty.’[25]

The global struggle against France between 1793 and 1815 (over twice as long as both of Britain’s twentieth-century world wars combined) revived a real threat of invasion. A small French force landed in Wales in 1797, followed by more substantial invasions of Ireland in 1796 and 1798 – one of the main reasons for incorporating Ireland into the United Kingdom in 1801. Indeed from 1798 to 1805 the invasion of England was Napoleon’s main strategic aim. ‘Eight hours of night in our favour would decide the fate of the universe,’ he blustered. ‘We have six centuries of insult to avenge.’ Britain was mobilised as never before. In 1804–5, nearly a tenth of the country’s 10.5 million people were directly involved in national defence. In these years, France became Britain’s bogeyman, with fears fanned by propagandists. ‘That perfidious, blood-thirsty nation, the French,’ one pamphlet claimed in 1793, was ‘the source of every evil you have experienced for a century past.’[26]

Only when he lost control of the seas after the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805 did Napoleon turn east against Prussia and then Russia. But he posed a new challenge in the form of economic warfare. His ‘Continental Blockade’ of Britain from 1806 and British retaliation against any state that cooperated with him proved the climax of this battle to control the narrow seas. It also had wider implications. The refusal of Portugal to join the blockade allowed the British to open a vital second front from 1808 in the Peninsular War, fighting Napoleon in Spain. And the Tsar’s refusal to maintain the blockade was a major factor in Napoleon’s hubristic invasion of Russia in 1812, which marked the beginning of his end. In 1814 and again in 1815 Britain was able to subsidise a coalition of three major powers (Prussia, Russia and Austria) as well as its own now-substantial army and thereby twice defeat the Little Emperor – culminating in the British-Prussian victory at Waterloo in June 1815.

The French wars from 1793 to 1815 led to a sharper definition of national borders. For the British, the sea between the two countries became generally known as ‘The English Channel’ – reflecting their claim that ‘the maritime frontier was defined by the French coast’. For the French, the waterway was known as ‘La Manche’ – the sleeve – indicating a looser conception of territorial waters. ‘The sea became an external limit of the French territory, without belonging to it,’ but the English claimed the sea as well.[27] Affirming Britain’s security interest in the other side of the Channel coast, in 1839 the Foreign Secretary, Lord Palmerston, orchestrated an international agreement to guarantee the independence and neutrality of Belgium, which had broken away from the United Kingdom of the Netherlands. France and Prussia were among the signatories. This had fateful consequences seventy-five years later.

After Waterloo there was periodic friction with France and occasional invasion scares, but, to quote historian François Crouzet, the French ‘never again picked up the gauntlet’. They ‘understood that they would not have a chance, and so backed down when the risk of war was serious, for example in 1840 and again in 1898’.[28] Gradually relations between Britain and France moved haltingly towards co-existence, then entente and eventually alliance – redefining Britain’s continental connection until 1940.

The Channel – transcended yet triumphant

During the century between 1815 and 1914, Britain tried to maintain its hybrid grand strategy – maritime and continental – by new means. Global expansion, often conducted by limited wars such as the conquest of Egypt in 1882, was combined with periodic bouts of calculating diplomacy to maintain a European balance. Throughout, large-scale wars such as the Crimea (1854–6) and South Africa (1899–1902) were the exception. But in the last decades of the nineteenth century – after the geopolitical turning points of American and German unification between 1861 and 1871 – the implications of Britain’s relative decline began to kick in. During the long eighteenth century the British had battled against a single foe, France, for European stability and global hegemony. The struggle was immense, but the chess game was essentially simple. By 1900, however, the country faced simultaneous challenges on the continent and globally from a variety of powers, even though Germany was the most threatening because closest to home. The first German war (1914–18) was won by Britain and France, but only with massive American help; in the second France quickly became irrelevant geopolitically and America all-important. In the process the Channel lost much of its strategic significance – transcended by the bomber and then the nuclear missile. Yet its psychological importance for British identity was triumphantly re-asserted by the events of 1940. The era of the two world wars requires closer attention because it has become central to national debate.

In the late-nineteenth century, Britain’s default response in the face of multiple challengers was a policy of selective ‘appeasement’ – in those days a perfectly respectable diplomatic term. It meant, according to historian Paul Kennedy, ‘satisfying grievances through rational negotiation and compromise, thereby avoiding the resort to an armed conflict which would be expensive, bloody, and possibly very dangerous’.[29] But the rationality and acceptability of appeasement was more obvious to the British than to others. ‘We are not a young people with an innocent record and a scanty inheritance,’ Churchill privately admitted in 1914. ‘We have got all we want in territory and our claim to be left in the unmolested enjoyment of vast and splendid possessions, mainly acquired by violence, largely maintained by force, often seems less reasonable to others than to us.’[30] He chose to omit the italicised phrases when quoting this memorandum in his war memoirs – a sign, presumably, of his awareness that they did not accord with what the British liked to present as their principled love of peace.

The United States, at least, could be managed around the turn of the century by calculated appeasement – backing down on points of friction, while playing up the economic and cultural ties between the two ‘Anglo-Saxon’ powers. The US was a force only in the Americas and the Pacific, with – at this stage – minimal political engagement in Europe. In Europe itself, Germany was not geographically a direct threat – unlike Napoleonic France had been. However, its aspirations under Kaiser Wilhelm II to become a ‘world power’ equal to the others did pose a serious challenge, especially in the 1900s when Germany built a large modern fleet to rival the Royal Navy. This prompted Britain to draw closer to France and Russia – colonial rivals in North Africa and the Indian subcontinent respectively but also European states that feared the growth of German military power. The Anglo–French entente of 1904 and the Anglo–Russian agreement of 1907 were intended to resolve, or at least reduce, imperial tensions in the interests of deterring Germany.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.