Полная версия

Island Stories: Britain and Its History in the Age of Brexit

ISLAND STORIES

BRITAIN AND ITS HISTORY

IN THE AGE OF BREXIT

David Reynolds

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2019

Copyright © David Reynolds 2019

Front cover photograph © Martin Parr/Magnum Photos

David Reynolds asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780008282318

Ebook Edition © October 2019 ISBN: 9780008282332

Version: 2019-09-13

Epigraph

We have got all we want in territory, and our claim to be left in the unmolested enjoyment of vast and splendid possessions, mainly acquired by violence, largely maintained by force, often seems less reasonable to others than to us.

Winston Churchill, 10 January 1914

Trade cannot flourish without security.

Lord Palmerston, 22 April 1860

Unless we change our ways and our direction, our greatness as a nation will soon be a footnote in the history books, a distant memory of an offshore island, lost in the mists of time, like Camelot, remembered kindly for its noble past.

Margaret Thatcher, 1 May 1979

Vote Leave. Take Back Control.

Brexit campaign slogan, 2016

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Epigraph

List of illustrations

Introduction: Brexit Means …?

1. Decline

2. Europe

3. Britain

4. Empire

5. Taking Control of Our Past

Notes

Index

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Also by David Reynolds

About the Publisher

List of illustrations

1. ‘Brexit means …’ © Christian Adams (Tim Benson, The Political Cartoon Gallery)

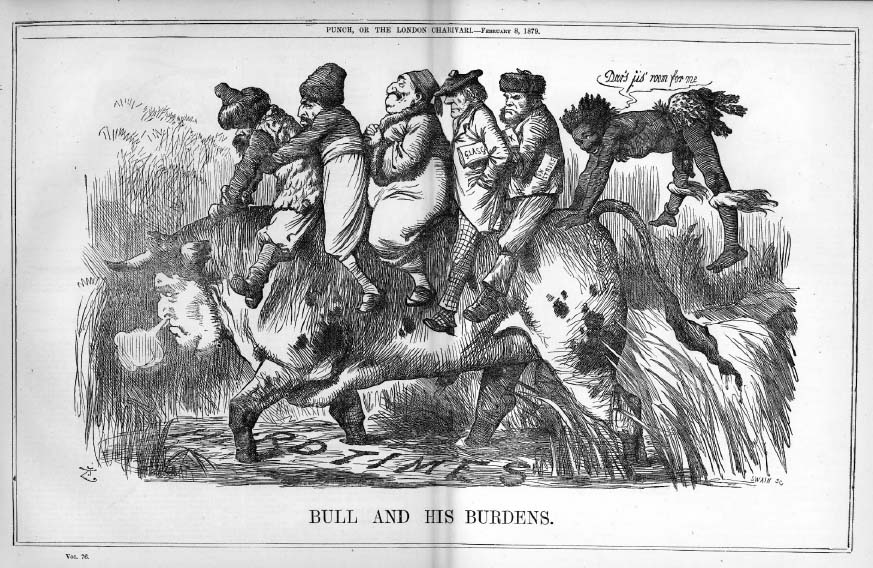

2. ‘Bull and his burdens’, John Tenniel © Punch, 8 February 1879, Vol 76

3. ‘We can fly the Union Jack instead of the white flags …’ © Cummings, Daily Express/Express Syndication, 16 June 1982

4. ‘Er, could I be the hind legs, please?’ © Vicky/Victor Weisz, Evening Standard, 6 December 1962

5. ‘The Double Deliverance’ (1621). © The Trustees of the British Museum.

6. ‘Very Well, Alone’. © David Low, Evening Standard, 18 June 1940.

7. ‘Come on in! Vite! The water’s wunderbar.’ © Cummings, Daily Express, 28 June 1989

8. ‘The United Kingdom: Liberate Scotland now …’ © Lindsay Foyle, 15 January 2012

9. Woodcut from James Cranford, ‘The Teares of Ireland’ (1642). © British Library Board/Bridgeman Images

10. ‘Massacre at Drogheda’ from Mary Frances Cusack, An Illustrated History of Ireland (1868)

11. Mr Punch reviews the fleet at Spithead, Punch, June 1897. © Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group/Getty Images

12. ‘Windrush Betrayal’. © Patrick Blower/Telegraph Media Group Ltd, Daily Telegraph, 18 April 2018

13. ‘The Aliens Act at Work’ (1906). © Jewish History Museum, London

14. ‘We need migrants …’ © Matt Pritchett/Telegraph Media Group Ltd, Daily Telegraph, 30 June 2017

15. ‘It’ll whisk you back to the sepia-tinted 1950s’. © Kipper Williams, In or Out of Europe (2016).

16. ‘Remainers Ahead’, © Grizelda, New Statesman, 13 April 2018

17. ‘Free at Last’ © Patrick Chappatte, New York Times, 23 June 2016.

Introduction

Brexit Means …?

On 23 June 2016, the British electorate voted to leave the European Union. The margin was arithmetically narrow, yet politically decisive: 51.89 per cent ‘Leave’ and 48.11 per cent ‘Remain’. ‘Leave’ meant ‘out’ but nobody in the governing class, let alone the country, had a clear idea where the country was going. No contingency planning for a ‘Leave’ vote had been undertaken by David Cameron, the Prime Minister who had called the referendum. And Theresa May, who succeeded Cameron after he abruptly resigned, lacked any coherent strategy for exiting an international organisation of which the UK had been a member for close to half a century. Her mantra ‘Brexit means Brexit’ initially sounded cleverly Delphic. By the end of her hapless premiership in July 2019, it had become a sick joke. There was still no clear idea what Brexit meant. The country’s future seemed more uncertain than at any time since 1940.

And not just its future; also its past. How should we tell the story of British history in the light of the referendum? Had the turn to ‘Europe’ in 1973 been just a blind alley? Or was the 2016 vote mere nostalgia for a world we (thought we) had lost? Bemused by both future and past, Brexit-era Britons feel challenged about their sense of national identity – because identity has to be rooted in a clear feeling about how we became what we are.

This is not a book about Brexit – its politics and negotiations: these will drag on for years. Instead, I ponder how to think about Britain’s history in the light of the Brexit debate. Because the country’s passionate arguments about the European Union raised big questions about the ways in which the British understand their past. About which moments they choose to celebrate and which to blot out. And about how to construct a national narrative linking past, present and future. Or, more exactly, national narratives – plural – because a central argument of this book is that there is no single story to be told – whatever politicians may wish us to believe.

For a century, there was a dominant national narrative: about the expansion of Britain into a global empire. In 1902 – after victory over the Boers in South Africa – the poet A. C. Benson added words to Edward Elgar’s Pomp and Circumstance ‘March No. 1’, extolling the ‘Land of Hope and Glory’:

Wider still and wider shall thy bounds be set,

God, who made thee mighty, make thee mightier yet

But after two world wars and rapid decolonisation, the ‘ever-mightier’ imperial theme rang hollow. In 1962, Dean Acheson, the former US Secretary of State, declared that Britain had ‘lost an empire’ but ‘not yet found a role’.[1] Over the next decade British leaders – Tory and Labour – tried to join the European Economic Community. But two French vetoes from President Charles de Gaulle blocked their way and it was not until 1973 that the UK (together with Ireland and Denmark) eventually became a member of the EEC. Even though Britain was always an ‘awkward partner’[2] – protesting about the size of its budget contributions and the EEC’s obsession with farm subsidies – for the next four decades or so the narrative did seem clear: the British had lost a global empire but found a European role.

But in 2016 that new role suddenly also seemed to be lost. During the referendum debate, various historical precedents and patterns were invoked to help frame Brexit Britain’s historical self-understanding. Much cited was ‘Our Finest Hour’ in the Second World War. Leaving the EU ‘would be the biggest stimulus to get our butts in gear that we have ever had’, declared billionaire Peter Hargreaves, a financier of Brexit. ‘It will be like Dunkirk again … Insecurity is fantastic.’[3] Developing the 1940 theme, Tory politician Boris Johnson asserted that the past 2,000 years of European history had been characterised by repeated attempts to unify Europe under a single government in order to recover the continent’s lost ‘golden age’ under the Romans. ‘Napoleon, Hitler, various people tried this out, and it ends tragically,’ he claimed. ‘The EU is an attempt to do this by different methods.’ The villains of the piece, in Johnson’s view, were once again the Germans. ‘The Euro has become a means by which superior German productivity is able to gain an absolutely unbeatable advantage over the whole Eurozone.’ He depicted Brexit as ‘a chance for the British people to be the heroes of Europe and to act as a voice of moderation and common sense, and to stop something getting in my view out of control … It is time for someone – it’s almost always the British in European history – to say, “We think a different approach is called for”.’[4]

Also touted as a historical guide for Britain’s future was the idea of the ‘Anglosphere’ – influenced by Winston Churchill’s A History of the English-Speaking Peoples from the 1950s – and even the concept of an ‘Imperial Federation’ with the ‘White Dominions’, as proposed by Joseph Chamberlain in the 1900s. Churchill biographer Andrew Roberts was one of those advocating CANZUK – a confederation of Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the UK – as potentially ‘the third pillar of Western Civilisation’, together with the USA and the EU. He argued that that ‘we must pick up where we left off in 1973’ when the ‘dream of the English-speaking peoples’ was ‘shattered by British entry into the EU’. Theresa May spoke in a similarly expansive vein when outlining her government’s vision of Brexit. ‘June the 23rd was not the moment Britain chose to step back from the world. It was the moment we chose to build a truly Global Britain.’ Although stating that she was ‘proud of our shared European heritage’, May insisted: ‘we are also a country that has always looked beyond Europe to the wider world. That is why we are one of the most racially diverse countries in Europe, one of the most multicultural members of the European Union.’[5]

Here were hints of how Brexit might be seen in historical perspective: as the latest attempt to resist a continental tyrant, or as the chance to resume a global role that had been rudely interrupted by joining the EU. But neat historical analogies are not adequate. Nor are simplified benchmarks like 1940 or 1973. We need to probe more deeply what is still often called ‘our island story’ – and to do so with greater geographical breadth and over a longer time span – in order to gain some perspective on the Brexit malaise.

* * *

Our Island Story was the title of Henrietta Marshall’s best-selling History of England for Boys and Girls, first published in 1905. In 2010 the education secretary Michael Gove told the Tory party conference that he would ‘put British history at the heart of a revived national curriculum’, so that ‘all pupils will learn our island story’. In 2014 Prime Minister David Cameron lauded Marshall’s stirring account of the country’s inexorable progress towards liberty, law and parliamentary government.[6] But today a simple ‘Whiggish’ narrative is implausible. This is a book about ‘stories’, plural – about different ways in which to see our complicated past. In particular, we need to move beyond the idea of a self-contained ‘island’, portrayed as adopting various roles over the centuries – empire, Europe, the globe – as if these could be tried on and then taken off, like a suit of clothes. In reality, ‘we’ have been ‘made’ by empire, Europe and the world as much as the other way round.

And the ‘we’ – the United Kingdom – has also been a shifting entity, a historically conflicted archipelago, comprising more than six thousand islands, and not a unitary fixed space occupied by a people whom many in England still tend to call, interchangeably, ‘British’ or ‘English’. [7] In particular, ‘our island story’ omits Ireland – ‘John Bull’s Other Island’, as George Bernard Shaw entitled his satirical comedy of 1904 about an English con man who dupes Irish villagers into mortgaging their homes so he can turn the place into an amusement park. Ireland was brought under English rule in the Norman period but never really subdued, despite the Acts of Union in 1801. Its centuries of turmoil and tragedy, in turn, had a profound impact on the island of Britain.

This, then, is a book about history, framed by geography. But it is also a book about ways of thinking, because being ‘islanded’ is a state of mind.[8] The English Channel did not always seem a great divide: for four centuries the Anglo-Norman kings ruled a domain that straddled it and treated water as a bridge rather than a barrier. The sense of ‘providential insularity’ came later, as a product of England’s Protestant Reformation, followed by several centuries of war against the continental Catholic ‘other’, embodied in Spain and then France. As the power of Protestantism waned in twentieth-century Britain, providential insularity was given a new lease of life by two wars against Germany, and especially by the way that 1940 has become inscribed in national history and popular memory.

Nor would the ‘island’ narrative have proved so enthralling had medieval English kings not created such a strong state, which they then tried to impose by force on their neighbours. The Welsh were incorporated in the 1530s, the Scots not until 1707, but thereafter – during the eighteenth, nineteenth and most of the twentieth centuries – the London government effectively directed the whole of ‘our’ island of Britain. Yet making the ‘other island’ across the Irish Sea ‘British’ as well proved a far more difficult task. The English failed to do so, but the struggle ebbed and flowed for centuries, costing several million lives through war and famine. At points along the way the ‘Irish Question’ also tested the unity of Britain itself – in the 1640s, for instance, when it was the catalyst for civil war, and in the Home Rule crisis before 1914. In 1920, after the brutal war of independence, it resulted in the partitioning of the island of Ireland in two between an independent Catholic state and an embattled, Protestant-dominated Ulster clinging on to its Britishness within the UK.

In the mid-1960s the rancorous issues of partition and sectarianism escalated into the three-decade long ‘Troubles’ in Northern Ireland, whose brutal violence was quelled only by the Good Friday agreement of 1998. This brought a ragged peace to Ulster and also redefined the political geometry of Ireland, opening up the border between the two states. Yet during the EU referendum debate, the Conservative and Unionist Party closed its eyes to recent history. Only after the vote to leave the EU did it start to grapple with the profound implications that Brexit would have for Northern Ireland, the peace process and the unity of the UK.

By the end of the twentieth century, both the Good Friday agreement and the institution of devolved governments in Scotland and Wales presaged a different set of relationships between and within the two main islands. In England the apparent indifference of London to the socio-economic problems of the regions, especially in the north, played a significant part in the Leave victory in 2016, and the failure of the Westminster Parliament to resolve – or even address – the challenges of Brexit aggravated this sense of alienation. Yet the saga of Britishness – forged by war and burnished by retelling – continues to exert immense power, whether deployed by politicians or dramatised in movies. Equally potent are the individual national stories of the Scots, Welsh and Irish – even of the English without the others[9] – all reinvigorated by the crisis of the Union. In a struggle for the future, the past really matters. Yet not just the past of the two islands and their tangled relations with continental Europe. The global dimension is equally important.

Developing as a seafaring nation from the sixteenth century, the English used their relative security from the Continent as both a sanctuary and a springboard. Exploiting their growing naval reach they were able to prey on foreign rivals, profit richly from the slave trade, open up markets and create settlements – first in the Caribbean and North America; later in the Indian subcontinent, Australasia and Africa. The wealth thereby generated played a critical part in Britain’s precocious industrial revolution. It also drew the country gradually and messily into a patchwork of formal empire, which the British then struggled to rule on the cheap in the face of bigger and stronger international challengers. By the 1970s, after two world wars and an often violent process of decolonisation, the British Empire has disappeared. But the UK remained a global economy, shaped by its commercial and financial past, and the stories of global greatness, now somehow disconnected from the empire project, still appealed to political and public nostalgia. More problematic legacies of empire, such as the slave trade or mass immigration, tended to be ignored in the grand narrative of our island’s worldwide reach.

Those simple words ‘island’ and ‘stories’ are, therefore, worthy of close examination. To do so we need to engage with ‘big history’ and the longue durée in ways which do justice to the English stamp on these islands’ histories without being narrowly Anglocentric. And although Island Stories has been prompted by the Brexit imbroglio, it reflects deeper concerns. There is now a profusion of innovative and detailed scholarly research, based on analysis of new sources and fresh insight into old sources. But much of this work takes the form of micro-histories, addressing narrow topics for an academic audience, and a good deal of it has been shaped by the ‘cultural turn’ – which privileges food, dress, and gender relations and frowns on political history as being antiquated and irrelevant. As a result, big-picture narratives have been left to popular writers skimming the surface, or to politicians advancing their own agenda. This short book is an attempt by one professional historian to start filling this gap, at a time when political and international history really matter.

The four main chapters outline and probe four alternative, if overlapping, ways of telling our island stories in the era of Brexit. They draw on some of the narratives that have been offered by famous voices of the twentieth century, such as Joseph Chamberlain, Winston Churchill, Hugh Gaitskell and Margaret Thatcher, and also by politicians of our own time including Boris Johnson and Jacob Rees-Mogg. But the chapters range far beyond the problems and personalities of the twentieth century, and offer some very long views to offset the national fixation with 1973 and 1940.

Each chapter explores an overarching theme, reflecting on the history of the last millennium. The first chapter ‘Decline’ looks at how and why Britain’s place in the world has changed in recent centuries, and whether the turn to Europe represented realistic statesmanship or a failure of national will. I also consider the country’s assets – both ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ power – in the Brexit era and the powerful hold of ‘heritage’ in the national culture. The second chapter looks more closely at Britain’s engagement with Europe, going back beyond the Protestant Reformation to the Anglo-Norman kings, and exploring that ambiguous role of the Channel as both barrier and bridge. The third chapter turns to the long history of Britain, tracing the impact of English empire-building on the archipelago and assessing the two Acts of Union in 1707 and 1801 that brought Scotland and then Ireland into the United Kingdom. The chapter also discusses the impacts of two world wars, 1990s devolution and the Brexit vote on the unity of the Union. The fourth chapter, ‘Empire’, emphasises the role of slavepower as well as seapower in making Britain great, but also examines how the ideology of freedom both promoted the empire and eroded it. In the last section of this chapter, ‘The Empire comes home’, I offer a historical context for the impassioned Brexit debate on immigration and reflect on a post-imperial country in which racist attitudes coexist with multiculturalism.

In the concluding chapter, ‘Taking Control of Our Past’, I reflect more generally on what the political feuding since 2016 reveals of Britain’s deeper problems in dealing with Brexit and also in coming to terms with its past. This is, of course, a personal view – on topics that are highly contested, for history has become an integral part of political argument in Brexitoxic Britain. Island Stories is a contribution to that fevered debate.

1

Decline

Of every reader, the attention will be excited by an history of the decline and fall of the Roman empire, the greatest, perhaps, and most awful scene in the history of mankind.

Edward Gibbon, 1788[1]

Thus began the final paragraph of Edward Gibbon’s magnum opus The History of the Rise, Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Volume one had appeared in 1776, just as the American colonies declared independence from Britain and proclaimed themselves a republic. The sixth and last volume was published in 1788, a year before ancien régime France was engulfed by revolution. Its fratricidal anarchy would spawn Napoleon’s continental empire.

Gibbon’s chronicle of the Pax Romana became a literary classic during the nineteenth century, as Britain saw off the Napoleonic challenge and grew into a global power – spanning the world from India to Africa, from the Near East to Australasia. By the end of the century the term Pax Britannica had entered the vernacular. But there were also creeping fears of imperial mortality – captured by Rudyard Kipling, the bard of empire, in his fin de siècle poem ‘Recessional’:

Far-called, our navies melt away;

On dune and headland sinks the fire:

Lo, all our pomp of yesterday

Is one with Nineveh and Tyre![2]

An 1879 Punch cartoon by John Tenniel shows John Bull the ox carrying the world’s woes on his back – Russia, Afghanistan, Egypt, Scotland (a recent financial scandal in Glasgow), a striker and a gleeful African warrior from the costly Zulu Wars.

Britain’s Victorian and Edwardian leaders sought strategies that might save their unlikely empire from a Roman fate. How best to deal with jealous rivals? By military confrontation, or selective appeasement? The first could sap the nation’s wealth and power; the latter risked letting in the barbarians by the back door. They also wrestled with the Roman tension between libertas and imperium, of civic virtues supposedly corrupted by militarism and luxury. Would British imperialism undermine political liberty at home? Conversely, would a freedom-loving people have the backbone to resist the jackals of the global jungle? These dilemmas became acute during the era of the two world wars.