Полная версия

You: Having a Baby: The Owner’s Manual to a Happy and Healthy Pregnancy

A good way to visualize the process: Let’s say that you and your partner each comes to your relationship with a set of favorite family recipes. You may contribute a blue-ribbon chili recipe, and your significant other may bring a killer lemon meringue pie to the table. But it’s not just two recipes, it’s hundreds, maybe thousands. (The human genome has some twenty to thirty thousand genes, after all.) Some on index cards, some in books, some on torn-up shreds of cocktail napkins. So what do you do with all these cranberry mold recipes? Stuff each and every one of them in the kitchen drawer. Now it’s hard to sift through them, you don’t have access to many of them, and you really can’t find what you want. Unless …(you knew there was an “unless” coming) you get them organized, say, by sticking hot pink Post-it notes on the recipes you really want to access quickly. You tag your favorite recipes, so you can quickly search, find, and put them into action.

That’s the way epigenetics works.

Genes are like recipes—they’re instructions to build something. Both mom and dad contribute a copy of their entire recipe book to their offspring, but for many genes, only one copy of each recipe will be used by the baby. Mom and dad have the same recipes (one for eye color, one for hair color, one for toenail growth rate, and so on), except they may have slightly different versions of those recipes (they’re called alleles). For example, eye genes are either brown or blue or green. For such genes, you express only the gene from your mom or dad—that is, only one copy is active, but not both. In some cases, neither copy will need to be expressed: Eye color matters only to eye cells; a liver cell doesn’t need either mom’s or dad’s eye color gene to be cranking away.

Figure 1.3 Cell Power On day one, we start with a single fertilized egg (called a zygote). Then cells divide and divide and divide, forming the biological structure of the fetus. By the end of the pregnancy, cells have divided a whopping forty – one times to end up with trillions of cells.

So how does a cell turn off the 24,999 genes it doesn’t need and turn on the few it does? Every cell—and there are around 200 different types in the body—needs to know which few genes are relevant for it, and, of those genes, whether mom’s or dad’s is going to be expressed. As with the kitchen drawer full of recipes, the genes alone are useless unless there’s a way to find what you need when you need it.

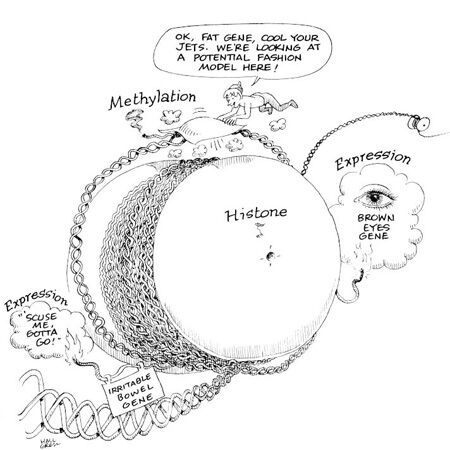

There is. Your body puts biological Post-it notes called epigenetic tags on certain genes to determine which genetic recipes get used. This tagging happens through a couple of chemical processes (such as methylation and acetylation), but guess what? Actions you take during your pregnancy can influence these processes and determine where the Post-it notes go and which genes will be expressed, ultimately affecting the health of your child. (See figure 1.4.)

When DNA gets tagged, it changes from being tightly wound around those histone proteins to being loosely wound, making the genes accessible and able to be expressed. At any given time, only 4 percent of your genes are in this accessible state, while the rest can’t be actively used in the body. By determining which genes are turned off and which are turned on, epigenetics is what makes you unique.

Here’s a point that will help you put epigenetics in perspective: We share 99.8 percent of the same DNA as a monkey, and any two babies share 99.9 percent of the same DNA. Heck, we even have 50 percent of the same DNA as a banana.* So genes alone cannot explain the diversity in the way we look, act, behave, and develop. How those genes are expressed plays a huge role in how vastly different we are from monkeys and how explicitly and subtly different we are from one another.

Figure 1.4 The DNA Drawer The way genes are expressed is a little like pulling recipes out of a drawer. They may be there, but it can take some work to find them.

Epigenetics in Action: What It Means to You

By about this time, we suspect that you’re asking yourself where you can buy yourself some epigenetic Post-it notes, because they sure as heck aren’t in aisle twenty-three of Walmart. The way epigenetics works during pregnancy is that stressors in the mother’s environment cause changes in the gene expression patterns of the fetus. Translation: The chemicals your baby is exposed to in utero via the foods you eat and the cigarettes you don’t inhale serve as biological light switches in your baby’s development. On, off, on, off—you decide how your child’s genes are expressed, even as early as conception. You don’t have total control, though. We still don’t know how you can change your baby’s eye color or how old he’ll be when his hair starts receding. But we do know how to influence some really important factors like your child’s weight and intelligence.

So there’s an important reason why we’re able to turn certain genes on and off. Our bodies have to adapt to a changing environment; that’s how a species survives, after all. But our ability to adapt would be much too slow if we had to wait generations for our genes to change through random mutation (the classical theory of evolution). Our bodies need some other kind of mechanism to allow us to adapt. Epigenetics gives our bodies the ability to influence which genes will be turned on—or as the scientists (and now you) say, expressed—or off, or partially on, depending on our immediate environment. Even more amazing is the fact that epigenetic changes don’t occur just when a baby is developing in the womb—they can also occur throughout life and can be passed down from generation to generation.

One of the best examples of epigenetics is called fetal programming. This refers not to teaching your child to use the remote control before birth, but rather to changes in gene expression that affect the growth and functioning of the placenta, the amazing organ that filters nutrients, oxygen, and waste between mother and baby (more on the placenta in chapter 2). If a mother’s genes for placental growth are turned off and the father’s genes are expressed, a thicker, richer placenta develops and channels more nutrients to the fetus. This puts more strain on the mother, because it both deprives her of nutrition she needs to remain healthy and causes her to carry a larger baby, which is associated with a host of risks. (See chapter 4.) If, instead, the mother’s genes are expressed, a smaller placenta develops and fewer nutrients get to the baby. In this case, the mother is protecting her interests—if this baby doesn’t make it, she can always try again.

Factoid: All of the epigenetic changes that you can make during the development of your fetus don’t just change the way your child’s genes are expressed. These changes can also be passed down from generation to generation—meaning that the small changes you make today can affect generations long after you’ve been said good-bye to—so your responsibility for creating a healthy environment for your offspring is even bigger than you may have thought.

Fetal programming also occurs when a baby is malnourished in utero—either because mom doesn’t eat properly during her pregnancy or because environmental toxins compromise the placenta’s ability to deliver adequate nutrition (more on this in the next chapter). In either case, you get the same result: a smaller baby. You may be asking, “So what if my baby is a couple of pounds smaller than average at birth? So what?” Here’s what:

In utero, if you feed your baby fewer nutrients, you’re programming your child to expect an environment of deprivation ex utero. So genes that cause the fetus to be very thrifty, metabolically speaking, are turned on. Once the baby is born and the external environment is not one of deprivation, that child will conserve more of the food it gets and become fatter, exhibiting what’s known as a thrifty phenotype (we refer to this in chapter 2). More fat storage equals an increased likelihood of becoming overweight and developing heart disease, type 2 diabetes, stroke, cancer, and osteoporosis as an adult. It’s similar to the reason why starvation diets don’t work: When your body thinks it’s faced with famine, it goes into fat-storage mode and your metabolism slows. Poor fetal nutrition may also permanently change the structure and development of vital organs such as the brain. In some cases, these epigenetic changes can even be passed on to future generations as well.

We do want to make one thing clear: If this is not your first pregnancy, don’t beat yourself up that you didn’t know much about epigenetics the last time around. None of us did, either. While epigenetics plays a role in what happens before birth, as we mentioned earlier, you can actually regulate gene activity after birth—for this child, for previous children, even for yourself. Also, if you fear you’ve already done something damaging to this baby, rest assured that human beings are a resilient lot; otherwise we’d have died out millennia ago. Let’s face it: Since 50 percent of pregnancies are unplanned, plenty of women inadvertently expose their babies to toxins like alcohol and tobacco. The key is to stop and make a YOU-turn,* reversing damaging behavior as soon as possible. Even the damage caused by smoking can be offset if you quit in the early part of your pregnancy.

Figure 1.5 Time for Change Through processes called methylation and acetylation, you can alter the way genes are expressed, as well as determine which genes are expressed. In other words, you can take certain actions that will influence whether some genes come to the forefront and whether others get locked away forever.

Another way to think about how epigenetics works is to think about how music is created. Consider your DNA to be the musical composition that will determine the individuality of your child; after all, there are zillions of way to put musical notes together. But the catch is that there are many different ways to interpret any given song. The way Johnny Cash sang a song would be different from the way a rocker would today and is way different from how a philharmonic orchestra would perform it.† Same song, different interpretations, and different results.

You and your partner each has your own set of DNA, and through your recent rendition of a boogie-woogie-woogie, you made your own biological song in the form of a baby. That genetic coding is indeed fixed, but you still have the ability to interpret the song and change the way your offspring’s genes are expressed. That, dear friends, should be music to your ears.

* Please cue “Let’s Get It On” by Marvin Gaye.

* Interestingly, too little of these hormones may lead to infertility or miscarriage, while an abundance may lead to twins and other multiple sets. More on this in “Fertility Issues” on page 380.

* True statement, not a joke.

* A YOU-Turn, as we introduced in YOU: On a Diet, refers to the fact that it’s not too late to make changes. The key is to identify when you’ve gone down the wrong road and get back on the right course as soon as you can.

† Not that one would.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.