Полная версия

You: Having a Baby: The Owner’s Manual to a Happy and Healthy Pregnancy

Your interest in sex will change somewhat during the course of pregnancy. In the first trimester, you’re likely to feel generally ill, not sexy. The middle trimester is the one in which most women report feeling best, so your interest in sex may go up again. By the third trimester, changes in your body and worries about hurting the baby may decrease your interest in sex again.

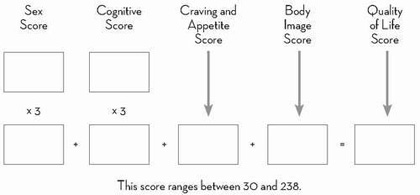

Keeping that in mind, if your score is:

3 to 6: Your interest in sex may actually have gone up since you got pregnant. Hooray for hormones! Remember that your body is going to change a lot over the course of pregnancy, and your interest in sex may vary during that time.

7 to 11: Your interest in sex is about what it was before you got pregnant. All of those changes in your body haven’t dampened your sexuality. Enjoy.

12 to 15: You’re showing less interest in sex than you may be used to. Don’t be too hard on yourself. Your body is going through a lot of changes. If you are feeling a much lower interest in sex even during the second trimester, you might want to check out our strategies for adding sensuality into your life, starting on page 172.

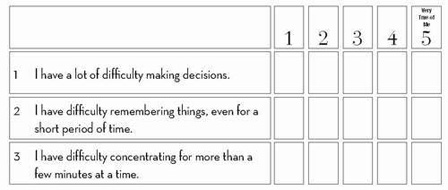

YOUR Quality of Life: Cognitive

Answer each of the following questions on a scale of 1 to 5, 5 being this is Very True of Me:

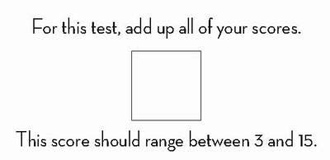

Cognitive Score

Interpreting Your Score

There seems to be little that is helpful about difficulties making decisions, remembering, and concentrating, particularly for women who are trying to maintain a high level of job performance during pregnancy. As frustrating as these experiences may be, think of them as evidence of the transformative power of pregnancy. Plus, they may be good for a few laughs when it’s all over.

If your score is:

3 to 6: Congratulations. Even though you’re pregnant, you’re sharp as a cat’s claw. Somehow, being pregnant has given you laser focus.

7 to 11: Chances are, you’re having a few lapses in thinking. You may feel more indecisive than you did before you got pregnant, and you may have more trouble remembering things than usual. That’s quite normal during pregnancy, though it can be annoying.

12 to 15: You seem to be having a lot of trouble thinking since you got pregnant. Some moderate thinking problems are quite common in pregnancy. If you feel that you have slipped quite a bit, then you need to review aspects of your lifestyle. Are you eating properly? Are you getting enough sleep? If you have other kids already, are you getting some help taking care of them?

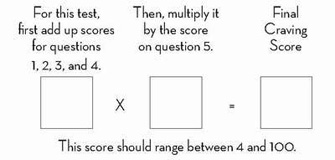

YOUR Quality of Life: Craving and Appetite

Answer each of the following questions on a scale of 1 to 5, 5 being this is Very True of Me:

Craving and Appetite Score

Interpreting Your Score

During pregnancy, it’s crucial that you get good nutrition. Your body is working overtime to keep up your energy and to help you build the brain and body of your developing baby. Pregnancy is not necessarily a time to be adventurous about food. Indeed, in evolutionary terms, there is probably good reason to eat only the foods that you’ve eaten successfully in the past. Morning sickness actually evolved as a protective adaptation. Early in pregnancy, your body is protecting your baby from anything that might be harmful to it. Still, even if you are experiencing a lot of nausea, you need to do your best to feed your baby and to take your prenatal vitamins.

If your score is:

4 to 30: You are probably eating fairly well. Do keep track of how much you’re eating and focus on foods that will give you energy and also help your developing baby. If you do experience some nausea, remember that it is quite normal. See our plan in chapter 3 to help you figure out your diet and do your best to provide your baby with the building blocks for a healthy brain and body. And don’t forget your vitamins.

31 to 50: Nausea is affecting your eating. You may not be making the best choices about your food, so it’s important to listen to your body. At the same time, there may be simple changes you can make to your diet that will make you feel a bit better and will give your baby the nutrients needed for development. See chapter 3 to help you plan your diet. And don’t forget your vitamins.

51 to 70: you’re experiencing moderate nausea, which is affecting the way you eat. In addition, you may be having some cravings. It might be time to make a few midcourse corrections and to work on your diet to give your baby the nutrients needed for healthy brain and body development. Chapter 3 will give you some great suggestions to get started. And don’t forget your vitamins.

71 to 100: Nausea is having a huge effect on what you eat. Pregnancy can be hard on your body and on your frame of mind. It’s hard to think happy thoughts with your head in the toilet bowl. If you’re in your first trimester, remember that that’s when the nausea is usually worst. If you can get through it, you can face anything. You’ll need to make the best choices you can about foods. See chapter 3 to help plan your diet. And don’t forget your vitamins.

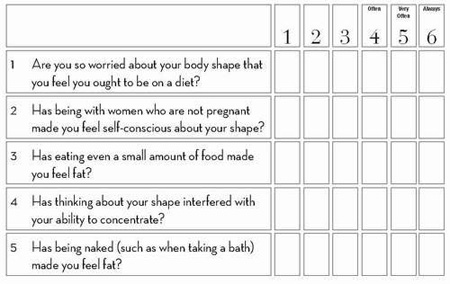

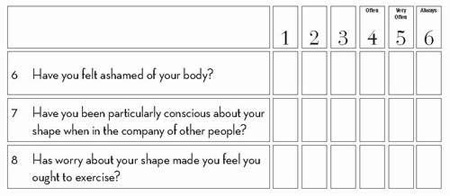

YOUR Quality of Life: Body Image

Answer the following questions about your feelings in the last four weeks (using the scale indicated)

Body Image Score

Interpreting Your Score

8 to 16: You don’t seem to be at all worried about your body. In many ways, that is good. Make sure, though, that you are still keeping in shape. Eat balanced meals and nutritious foods. Exercise is good for you and for your baby. See page 310 for our exercise plan.

17 to 32: You have a small amount of concern about your body image, but it is not excessive. Pregnancy is a time of changes in your body. At the same time, you do need to make sure to take care of your body. A healthy body is good for you and your baby, and it will make it easier for you to have a body you like after you give birth. Make sure that you eat balanced meals and nutritious foods. Remember that exercise is good for you and for your baby.

33 to 48: You have quite a bit of concern about your body. It’s really crucial that you exercise during pregnancy and that you eat balanced, nutritious meals. You are eating for you and for your baby. It is possible that you have gained too much weight and that your doctor may recommend ways to help solve any problems that have come up. However, it is also possible that your weight gain is quite normal. (See page 68 for guidelines for gaining weight.)

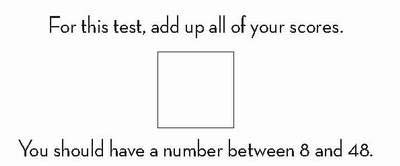

YOUR Quality of Life: Overall Score

To get a sense of how you’re doing overall right now, we’re going to create a total score for Quality of Life. Enter the scores from the four tests that make up the Quality of Life survey in the boxes as shown below.

On many tests, you aim to get the highest score possible. This test is a little different. When your Quality of Life score is low (close to 30), your life is in balance.

Trying to maintain your quality-of-life balance during pregnancy is a bit like trying to walk on a four-inch-wide gymnastics balance beam with your pregnant body. It’s not as easy as it looks, and it doesn’t look easy. It is also possible you have not gained enough weight and are overly concerned about your own shape without attending to what your baby may need. If that describes you, see your OB as soon as possible, and perhaps a nutritionist, to make sure you are not underfeeding the baby unintentionally.

So most people are probably not perfectly in balance. Remember that for every gymnast who nails a perfect routine on the balance beam at the Olympics, there are hundreds who slip a little or even fall flat. The trick is just to keep getting up there and trying to balance again.

Interpreting Your Overall Score

30 to 70: Congratulations! You have achieved some real balance in your pregnant life. There’s still a lot ahead of you, but you’re quite centered so far.

71 to 150: Like most pregnant women, there are days when you have it together and days when things seem beyond your grasp. Keep on reading. We have a lot of tips to help keep you centered.

151 to 238: Between your nausea, your inability to think straight, and your negative feelings about your body, you’re probably looking at pregnancy as more like a never-ending traffic jam than an Olympic gymnastics event. All the same, you’re in the middle of one of life’s peak experiences. We have a lot of tips here to make your worst days more bearable. Hang in there, and read on.

* That book is two shelves over.

† In this day and age, of course, traditional intercourse isn’t the only way to make a baby.

* Apologies to anyone named Horatio Horace Humphrey.

1 Nice Genes A New Twist on Genetics Teaches Us How a Baby Really Develops

Back in tenth-grade biology class, you were probably taught—as were we—that the unique combination of genes you received from your mom and dad (your genotype) was responsible for everything that followed: the color of your eyes, the size of your feet, your love of lasagna, your hatred for all eight-legged and no-legged creatures. To a certain extent, that’s true, but over the past few years, studies have suggested that classical genetics may be only part of the picture. It’s not just your genes that determine who you are, but which of those genes are turned on, or expressed, and to what degree they are expressed—a cutting-edge field called epigenetics. While you can’t control which genes you pass on to your child, you do have some influence over which genes are expressed, affecting what features are seen in your baby (his phenotype). In this chapter, after giving you a brief refresher on the basic biology of what happens after your life-changing evening of romantic rasslin’, we’re going to introduce you to a new subject:YOU-ology—how what you eat, breathe, and even feel can affect the long-term health of your child.

Two to One: The Biology of Conception

We trust that you know the ins and outs of the process that involves his part A and her part B, so we’ll skip what happens deep under the satin sheets and focus on the miracle deep below the flesh and deep inside the body—that is, how the egg and sperm come together.*

The Eggs

Factoid: Though it happens rarely, women who lose their corpus luteum (through a ruptured cyst, for example) might need a progesterone supplement during the first trimester to help maintain the uterine lining until a placenta forms. Other candidates for progesterone supplementation include women who have a history of miscarriages, perimenopausal women, and those having in vitro fertilizations.

On the female side of the conception equation lie her eggs, which are fully formed and stowed away in her ovaries from before birth. Each mature egg contains one copy of each gene in the human genome—half the amount necessary for life. The maximum number of eggs that a woman will ever have is the number she has when she is a twenty-week-old fetus. She’ll have about 7 million of them then, 600,000 when she’s born, and about 400,000 at puberty. Once a woman hits puberty and menstruation begins, her ovaries release one of those eggs every twenty-eight or so days. During each cycle, even though multiple eggs start to develop, hormonal signals ensure that only a single egg will be released and the other eggs will regress. (It’s not wise evolutionarily to blow them all at once, so the body gives females an approximately thirty-year window in which to conceive.) Hormones also work to mature that ready-to-drop egg and to pop a hole in its sac. That hole works as an escape hatch, so the egg can slip out of the ovary and travel down the Fallopian tube, where it may be fertilized by sperm.* Tissue left behind in the ovary after the egg is released, called the corpus luteum, will produce hormones essential to successful pregnancy if the egg is fertilized.

The Sperm

On the other side of the equation, of course, we have those little swimming sperm. As with a woman’s eggs, each sperm contains a single copy of each gene in the human genome. Unlike women, men don’t have a preset number of their reproductive players. In fact, a man produces more sperm in each ejaculation than the total number of eggs that a woman is endowed with for life. (Evolutionarily, a man can continue reproducing for the majority of his adult life, maximizing the chance of passing on his genes. A woman’s reproductive life is limited to the younger years of her life because of the physical strain of pregnancy, childbirth, breast-feeding, and child rearing.)

A man’s sperm, which is carried in semen that’s made by glands such as the prostate, is stored in a duct called the vas deferens. When a man ejaculates, the sperm-carrying semen fires out through the urethra in a seek-and-conquer mission. It may seem that all these millions of sperm are racing one another to the finish. But just like a Tour de France cycling team, the sperm have different roles. Some are deemed the leaders of the pack, trying to be the first to cross the line. Others are designed to assist, specifically by blocking other men’s sperm from making it to the finish line. Competitive little game going on in there, eh? The goal of pregnancy, of course, is for a sperm to find an egg during a precise window of opportunity and fertilize it.

Print Shop

The word imprinting may sound like something you’ve heard on CSI, but it’s actually a form of epigenetics. Even though two copies of a given gene are inherited, one from mom and one from dad, in certain circumstances, one is permanently turned off. The nonexpressed copy is said to be imprinted. As of now, we know of at least eighty genes that are imprinted by epigenetic markers, causing them to be active or inactive in the offspring based on parent of origin. In general, expressed genes that are inherited from the mother conserve maternal resources and limit fetal growth, while expressed genes inherited from the father promote fetal growth, even if it means hurting the mother.

Problems can occur when genes that are supposed to be imprinted, or turned off, are not, or when the wrong parent’s gene is imprinted. The gene for the chemical messenger called insulinlike growth factor 2 (IGF2) is normally turned on from the father and off from the mother. If the mother’s copy is not turned off, the child can develop Wilms’ tumor, a cancer of the kidney. Loss of imprinting of the mother’s IGF2 gene later in life can contribute to age-related cancers, including cancers of the prostate and colon.

The Union

The purpose of an orgasm isn’t solely to make you feel good or provide gossip fodder for the neighbors. The biological purpose is to better the odds that this union between sperm and egg takes place.

On the woman’s side, the mucous membranes that line the vaginal walls release fluids during intercourse so that the penis can slide with just the right amount of friction. As intensity and sensations build, the woman’s brain tells the vagina and nearby muscles to contract. That contraction brings the penis in deeper. Why does that matter? It increases the chance of his sperm getting closer to the target. During an orgasm, the cervix, located at the top of the vagina, dips down like an anteater and sucks semen up into the cervix (the cervix is a passageway connecting the top of the vagina and bottom of the uterus). The sperm is trapped in the cervical mucus

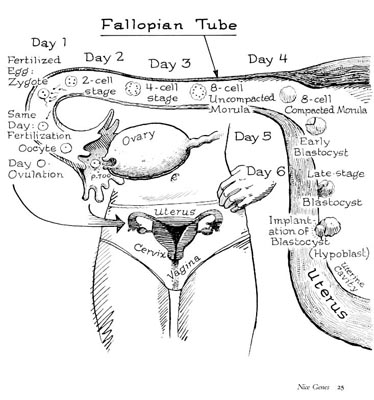

Figure 1.1 Tube Ride In the Fallopian tube, an egg has about twenty-four hours in which it may be fertilized. Once the sperm does so, the fragile combo, the blastocyst, multiplies its cells and must implant in the uterine wall to endure the 280-day pregnancy. Even if you try to summit Everest, this is the most dangerous journey you will ever take.

What’s Age Got to Do With It?

We all know plenty of people who have made the classic clock-ticking jokes about aging women who want kids. But what does that really mean? Before ovulation, eggs have two copies of each of the twenty-three chromosomes. They’re lined up waiting for the signal to divide for mom’s entire life. Unfortunately, the little spindles that pull chromosomes apart don’t work as well when they’ve been waiting for four decades. Instead of a clean break, two copies may be pulled to one side and none to the other. That’s what leads to an increased risk of chromosomal abnormalities such as Down syndrome and an increase in miscarriages in older moms.

Now, that doesn’t let pop totally off the hook. Older men’s (as in over 35) sperm have been linked to an increase in birth defects and autism, as well as an increased difficulty conceiving. New evidence even suggests that children born to older dads score lower on various brain tests through the age of seven.

While older parents may be better equipped to handle some aspects of pregnancy and child rearing (like some of the stresses and emotional wear and tear), and may be better able to support their children financially, there are some physiological trade-offs that you’ll want to consider if you are making a decision about when to have children.

until the release of the egg, and a signal then lets the sperm start the competitive swim up into the uterus.

While it’s by no means necessary to have an orgasm to get pregnant, women who orgasm between one minute before and forty-five minutes after their partner’s ejaculation have a higher tendency to retain sperm than those who don’t have an orgasm. On the man’s side, orgasm is required, because during orgasm fireworks in the brain cause involuntary contractions in lots of muscles in his body. Those contractions help him penetrate deeper and squeeze the prostate to eject sperm deep into the vagina.

Now, the actual fertilization process happens this way: After the egg drops from the ovary, it travels through the Fallopian tube, where there’s about a twenty-four-hour window when it can be fertilized. Since sperm live for up to a week in the cervix (they die after a few minutes of hitting the air), it’s not necessary for two people to have sex precisely when ovulation occurs, as many assume. In fact, conception is more likely to happen if sex occurs a couple days before the egg is released from the ovary. (See “Fertility Issues” on page 380 for more about getting the timing right.)

If all goes according to plan, the sperm meets the egg in the Fallopian tube, and the two half genomes unite to form a complete set of genes containing all the DNA necessary to make a new human being. The fertilized egg says thank you very much and moves along to the uterus. There it will attach to the uterine lining and begin the amazing process of becoming a baby.

YOU-ology: A New Approach to Genes

One of the most miraculous processes in nature, aside from the formation of such things as the Grand Canyon and the hammerhead shark, has to be how we grow from a single fertilized egg cell to the trillions of cells that make up a new person.

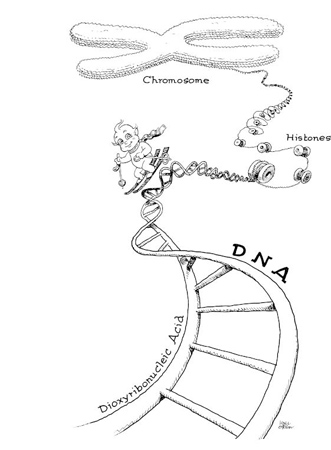

Human cells have twenty-three pairs of chromosomes, structures that hold our DNA. The DNA acts as a complete set of instructions that tells our bodies how to develop. Individual genes are short sequences of these instructions that regulate each of our traits. (See figure 1.2.) As you might imagine, given the fact that virtually every person in this world looks different from every other, the nearly infinite possible combinations of maternal and paternal DNA are what give us our individuality. When maternal brown eyes and maternal red hair get paired with paternal blue eyes and paternal blond hair, there are four possible combinations for offspring, right? Brown eyes – blond hair, brown eyes-red hair, blue eyes-blond hair, blue eyes – red hair. Extrapolate that scenario out to twenty-three chromosomes, and the possible combinations become mind-boggling, unless scientific notation is your thing: 223, or about 8.3 million, combinations—meaning that there’s about a 1 in 8 million chance that the same mother and the same father would have two kids with the exact same coding (excluding identical twins). (See figure 1.3.)

But that’s only part of the story. Consider identical twins. They get dealt exactly the same DNA, but they may develop different traits down the line: One may have allergies and the other may not, one may develop a particular disease and the other may not, one may be able to play the piano without ever learning how to read music, while the other can’t carry a tune with a dump truck. What accounts for these differences? Something in their environment—potentially as early as in utero—affected the expression of their genes differently. That something is called epigenetics.

Figure 1.2 All Wound Up Storing more data than any computer, each chromosome contains all the information needed to give you a base for your physical and emotional characteristics. What we can learn from epigenetics is that you have the power to influence the course of biological destiny.

Here’s how it works:

Each cell in the human body contains about 2 meters of DNA that’s packed into a tiny nucleus that’s only about 5 micrometers in diameter. That’s the rough equivalent of stuffing two thousand miles of sewing thread into a space the size of a tennis ball. As with thread, DNA is wound around spools of proteins called histones. Not all of your DNA gets expressed, or used to create proteins, in every cell; in fact, most of the spools of DNA in each cell are stored away, some never to be seen or heard of again.