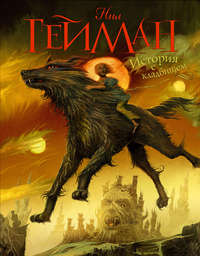

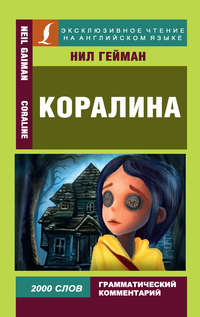

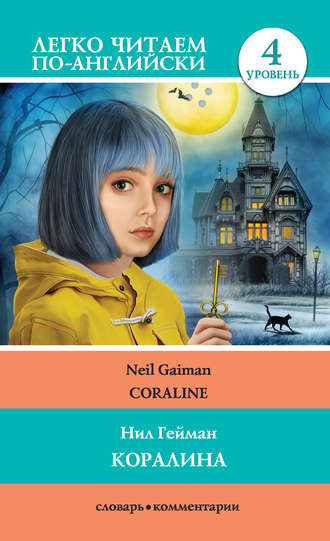

Коралина / Coraline

Полная версия

Коралина / Coraline

Жанр: ужасы / мистикасказкидетские приключениямистикаизучение языкованглийский языкпараллельные мирылексический материалтекстовый материалневероятные приключенияUpper-Intermediate levelзнания и навыкикниги для чтения на английском языке

Язык: Английский

Год издания: 2019

Добавлена:

Серия «Легко читаем по-английски»

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента

Купить и скачать всю книгу