Полная версия

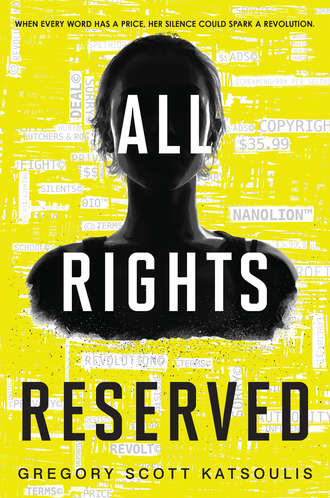

All Rights Reserved: the must read YA dystopian thriller that will have you on the edge of your seat!

Saretha had wiped all evidence of sadness from her face. She looked bright and eager, like she did whenever she was on her way to work, though there was something less ready in her posture. She fixated intently on the screen, and it felt like she was purposely avoiding my gaze. She had not looked at me since the letter came. She had not spoken to me. Out of the corner of my eye earlier, I saw she had pulled up my speech for a moment, but then said to herself, “It doesn’t matter now,” and flicked it away. She was right. Even if I read it now, Butchers & Rog would not back down on Saretha.

“Despite what may be implied by the letter, you can use Miss Harving’s likeness within the private comfort of your home without concern for civil, criminal or financial penalties, provided, of course, that you do not charge a fee or offer promotion in conjunction with the viewing of said likeness.” He smiled.

“And I was going to sell tickets,” Sam said, snapping his fingers.

It took Attorney Holt a moment to realize Sam was being sarcastic. Saretha did not admonish him, and that worried me. She waited for more of the good news.

“However.” Attorney Holt cleared his throat again. No more good news, apparently. “Any transmissions from your home, such as ScreenChat™, constitute a breach of Copyright Law and, as such, you will need to make provisions to have your likeness altered, obscured or blocked through electronic pixelation or other means.”

My Cuff popped an Ad for ScreenChat™ Enhanced, which promised to make you look better. I knew how this worked—they installed more flattering lighting and squeezed the image to make you look thinner. I had long ago adjusted the lighting in our unit to make it as pleasant as the space would allow.

“Technically, I should have you stand outside of frame, but, as this is privileged communication, I think we can make an exception.” Attorney Holt smiled in the hope Saretha would smile back. She obliged weakly.

“You can easily purchase facial recognition software that will pixelate or block your image on any digitized transmission, but, of course, this does not solve the larger problem of what might happen outside the home.”

Another Ad popped up, this one for PixelMate™ PixelBlock® software. We were all familiar with Blocking. It was becoming increasingly common for companies to Block certain imagery in-eye using the overlays on your corneal membranes. An expensive perfume bottle, for example, might appear as a blocky mess of color if you fell too far out of the company’s target demographic. People who were too poor, or fell too far in debt, could end up with a full-blown case of The Blocks. Famous faces, clothes, architecture—anything valued over $500 all became blurred. Silas Rog kept his face blocked at all times to show just how important he was; no one could afford to see him.

It could be debilitating to navigate through the world with The Blocks on—which is why, when the police arrested people, they instituted The Blocks as a way of subduing criminals.

“Outside of the home,” Holt said, “in public, you will need to alter your likeness by physical means.”

Saretha mouthed the word physical and was charged for it.

“What does that mean, physical?” Sam asked. Saretha shushed him. Arkansas was getting to that. Our bill ticked higher—$4,328.19.

Holt glanced down uncomfortably at his Pad. “I know this is distressing. If you don’t like the idea, I could try to broker a deal to use Miss Harving’s likeness, but in the hands of Butchers & Rog, I suspect such a deal would be unpalatable.” He paused to see how this would go down with us. No one said a word, so he went on.

“You could have your face altered through plastic surgery. I could arrange for a consultation. I know a few people who will consult for a minimal fee and offer payment plans on your baseline debt. I recommend breast enhancements as well, if you are going that direction. They are generally beneficial in a courtroom setting. Actually, they are a fine investment for any young girl looking to improve her financial opportunities and sponsorship potential.” He paused again. I couldn’t look at him.

“No,” Saretha said. A small vibration rang out as her Cuff charged her.

“To the breasts?” he asked.

“To all of it,” Saretha said clearly, tucking her hair behind one ear.

I looked at her. I had envied how she looked, but now I just felt shame blooming in my gut. I had brought this on her. Butchers & Rog had shot the arrow, but I had drawn the target. I swallowed hard. How could I even begin to apologize? How could I make this right? I ducked my head, tilting into Saretha’s field of vision, but she showed no sign of noticing.

“Maybe this is an opportunity,” Saretha said, sitting up taller.

Holt’s mouth hung open in confusion. Saretha flashed her incredible smile.

“Maybe I could meet her. We could talk. We could work something out.”

My heart sank. I prayed she did not still think she would get to be in a movie with Miss Harving. It was a childish fantasy years ago, even when she was newly fifteen and we first saw Carol Amanda Harving in her debut film. Saretha thought she could play her sister.

“Can’t we talk to her?” Saretha continued.

“What do you think she would say?” Arkansas Holt seemed a little taken aback, but then he sighed. “It’s irrelevant. Silas Rog would never allow it. I don’t think it is any secret that Butchers & Rog have it in for you. I can’t beat them in court. I’m probably the only Lawyer stupid enough to even provide counsel. The best we can hope for now is to roll over and pray it isn’t made worse for you. For some reason, Butchers & Rog haven’t just taken everything, which is a small miracle.”

“Okay,” Saretha said. Her voice quavered a little.

“You could consider deconstructive surgery,” he suggested, circling his own face with a finger through the air. Saretha’s brow knit. She did not understand.

“They could reconfigure your face, like plastic surgery, but without the goal of improving your features. It is significantly cheaper, as they need not be so careful.”

“Why don’t we just do it ourselves?” Sam burst out.

“You could do that,” Holt plowed forward. “Though I am legally bound to inform you this would not be safe or sanitary.”

Another Ad popped up. Zockroft™: When things aren’t going your way, it read. A row of happy little pills appeared beneath it.

Holt put the Pad down. “Please understand that if you don’t make a choice, they will. They have the legal right to prevent your face from potentially entering the public sphere if you fail to desist.”

I felt a little sick. Was it their plan to disfigure her? Or take her away? Or worse?

“Let’s not let it come to that,” he said, picking up his Pad again.

“Couldn’t she wear a mask?” Sam asked. “Like a Product Placer or something?”

“No!” Holt said, scrolling through more legal documents. “Product Placers have a special exemption. Maybe. Who even knows what they wear?”

They wore masks. Everyone knew that. They weren’t supposed to be seen, but it did happen. Ninety-nine out of one hundred times, if a Placer was spotted, no one said a word. Why cause trouble? Why upset them? It was an unspoken rule that if you happened upon Placers, you watched quietly and did not follow or draw attention to them. Everyone liked a good Product Placement, and often people were rewarded for their silence with a surprise Placement. Norflo Juarze thought this was how our building got inks that one time.

For Saretha, though, wearing a mask would be a breach of the Patriots Act©. How would she be identified? How would advertisers know who to market to?

Our bill was blinking now—$7,328.55. We were approaching our debt ceiling for the month. Holt could see this, too. He sighed again, like it pained him to feel anything.

“Stay home,” he instructed briskly. “They can’t issue a complaint if you stay in your private residence.”

“My job?” Saretha groaned.

“Oh.” Holt laughed sadly. “You can’t work in public. They could accuse you of tacitly using Miss Harving’s likeness in the promotion of a product or business. Miss Harving would be entitled to those earnings and then whatever damages Butchers & Rog could dream up. It is utterly out of the question.”

The blinking grew faster. My heart rate went with it.

“Mrs. Nince,” Saretha muttered, imagining the wrath of her boss.

I hated Mrs. Nince, though I’d never met her. During Saretha’s first week of work, the woman had “accidentally” jabbed Saretha in the arm with a leather punch, leaving a small crescent-shaped scar in the flesh above Saretha’s right elbow. She’d sued Saretha $90 for causing a workplace accident.

“Speth can work. She’s past Last Day, and she doesn’t look like anyone,” Holt suggested.

I almost snorted. What kind of job did he think I could get?

Attorney Holt’s face contorted as he remembered one more thing. He looked conflicted, then tapped at his Cuff a few times and looked to the left and the right, as if he were afraid to be observed.

“You can’t get sick,” he said. His bill had stopped creeping up. He was paying for this bit of advice himself. I don’t know why he did it. Compassion is trained out of Lawyers, but Arkansas Holt wasn’t a very good Lawyer. Had some small bit of kindness survived? “You can’t go to a hospital, because that would put your face in public. You can’t get arrested or taken into Collection, either.”

Saretha’s eyes seemed to go blank. Sam’s lips formed a question, but he didn’t need to ask. We all realized the same thing.

While we’d never had any significant hope of paying off our debt in our lifetimes, we had to keep making progress. Our parents’ income and our income had to be at a high enough level to chip away at our debt. We lived in constant fear of losing ground, because if the algorithms foresaw us earning under our minimum payments, they would take Saretha into Collection. Until Holt’s visit, we were afraid of her being sent to Indenture like my parents, stuck working a farm or much, much worse. But now, if that happened, they would disfigure her first.

“Just stay safe and healthy and home,” Holt counseled.

The Zockroft™ Ad popped up again, this time with a name. Saretha Jime: Be Positive! it read. The pills danced.

“We can talk again at the start of your next billing cycle,” Arkansas said, his attention falling away. “Perhaps I’ll think of something,” he mumbled quickly. Before we could agree, the call winked out and an Ad screamed at us to buy new, fluffier toilet tissue. I sat numbly by Saretha, the screeching noise from the Ad blasting over us like an unforgiving wind. I stood and shut the whole wall panel off.

Saretha buried her head in her hands. What were we going to do?

A CRESCENT: $10.98

Mrs. Nince was the kind of woman who wore a cinched half-corset and tight black jeans, even though she was sixty years old and weighed about eighty pounds. She had jet-black hair interwoven with delicate, sharp, printed shapes. Her face had been rebuilt at least a dozen times, and it looked like something from a creepy wax museum. She thought her look was stylish, though that wasn’t the word she used to describe it. She called it modish, because she owned that word. She bragged about how she’d watched auctions for years for a word this good to be sold. I think she just took what she could find. Modish wasn’t exactly a common word.

Mrs. Nince wanted people to say it so she could make money. Words, she knew, were good investments.

Saretha had worked under her for two years and never said a bad word about her. She never described Mrs. Nince’s face as pinched and cruel. She never mentioned how painful the clothes must have been to model. In fact, she never mentioned Mrs. Nince at all, if she could help it, because Saretha never liked to say anything bad.

Her boutique was north, part of the shops above Falxo Park, but far enough along the outer ring that it was in the next section, the Duodecimo. I’d never understood why that section had a Latin name. The buildings were still printed to look French. That was baffling, too. The obsession with French style supposedly came from the period when the French let all their Intellectual Property rights lapse, but I’d only heard that from kids passing it on. It didn’t seem like the full story. My history classes were weirdly devoid of information about the world outside our nation’s borders.

At the shop, Sam asked for Mrs. Nince, and a pretty girl in a painfully tight silver corset and tight white jeans scurried awkwardly into the back to fetch her. I don’t think she could bend at the knees.

We waited.

“Litsa, pour l’amour de Dieu!” a voice croaked. The girl backed out the door and nearly fell over.

Mrs. Nince stepped out of her office, locked the door behind her conspicuously, then turned to us expectantly as she pocketed the key.

“We were hoping,” Sam said, trying to sound both humble and professional, “you might consider letting my sister Speth take over Saretha’s job?”

I tried my best to smile Saretha’s smile. I caught sight of myself in the mirror. My short hair stuck out at odd angles to keep the style in the public domain. I had to be careful not to let it get too neat, or it would drift over into a Patented Pixie 9®. My eyes were red and puffy and opened too wide.

I looked ridiculous. I dialed my expression down to a more appropriate level.

“Her?” Mrs. Nince asked, drawing a long finger up and down in the air to indicate what an inferior specimen I was. Then she drew herself up and held a hand to the silver rim of her Cuff, indicating she would like us to pay for her speaks. The Cuff vibrated—99¢. The gesture was not free. Sam tapped in our family code, and Mrs. Nince relaxed just a hair.

“Litsa, get back to work,” she growled at the girl who was hovering nearby. The girl scurried off, the top and bottom halves of her body seeming to twist without coordination, the corset, perhaps, hampering communication from top to bottom. Phlip and Vitgo wanted to see her nude? Why was this supposed to be attractive? It looked warped and creepy to me.

“What is it that you wanted?”

“We know Saretha can’t work here anymore...” Sam began.

Mrs. Nince rolled her eyes. “Saretha’s unapproved departure from my employ was extraordinarily inconvenient.”

“But Speth...”

“Speth,” Mrs. Nince spit the word out with even more distaste than Mrs. Harris. She shuddered. “At least it isn’t one of those tedious French names like Claudette or Mathilde. Those are rather passé, and so costly.”

She looked me over again—probably jamming me into a corset in her mind—and grimaced. “Why would I want to hire her? She’s flat as a board.”

My face heated up. Sam took a breath. He didn’t want to be part of this conversation. Neither did I. I hated this woman, and it set my jaw tight to think about working for her. I pictured the crescent-shaped scar she’d punched into Saretha’s arm and had to work hard to clear the image from my mind.

“People might be curious...” Sam began. “Affluents...they might like to see if they can get her to talk.”

“How would that be good for business?” Mrs. Nince asked. “Why should I want people distracted by some carnival game of trying to make a Silent Freak talk when they should be buying my modish clothes?”

Sam tried to answer this, but she talked right over him.

“My modish customers don’t want some oddball Silent Freak hovering over them. Can you imagine? You ask the Silent Freak how you look in these modish jeans, or you ask the Silent Freak how many ribs should be removed for a modish Frid-Tube™ Halter, or you ask the Silent Freak if we’re having a sale, and the Silent Freak would just stare and stare like a farm animal.”

“Don’t call her that,” Sam growled.

“Farm animal, or Silent Freak?” Mrs. Nince asked innocently. “Isn’t her silence unusual and freakish? She can’t control it. Isn’t that what we’re supposed to believe? It’s a malformation; the poor Silent Freak can’t speak because her idiot boyfriend killed himself.”

I said nothing, but I thought so many things. She was a noxious, sour, self-important excuse for a human being. I struggled to keep my loathing from showing. How had Saretha been able to stand working for her?

She stepped to within an inch of my face. “Silent Freak,” she said, calmly, as if I should nod so we could all agree.

There was something odd about how pleased she was with herself. Was she trying to goad me into talking? It didn’t seem like it. Despite her overall hatefulness, she seemed more than happy to keep talking to us—at least until Sam spoke.

“You waxy old prune,” Sam burst out. His brow was furrowed, and his cheeks were flushed red. “Everyone can see you slathered on your makeup and had some doctor pull your face folds back. It doesn’t fool anyone into thinking you’re younger.”

I wished I could have said those things. Once, I would have. Sam and I were a lot alike that way.

Mrs. Nince stepped away and pretended to pick at something under a long curling black nail. “Silent Freak,” she said. “So much better and more descriptive than Silent Girl.”

Sam reached for her Cuff, to stop paying for her words, but she held her arm up and away.

“I made a lovely purchase after the incident at your party. I bought the Trademark to the phrase Silent Freak™.” Sam feinted left and quickly moved right. She whipped her Cuff arm back behind her, but teetered a little on her heels.

“I do hope you will stay in the news.” She grinned, her thin, translucent teeth glistening. She must have really hated me to go to the trouble of obtaining the phrase, coordinating with the owners of the words silent and freak, offering a cut of the profits and paying all the Lawyers’ fees.

“I’d love for everyone to keep talking about the Silent Freak™,” she hissed.

I reached out suddenly, and my movement surprised her. I grabbed her arm and held it fast. I wanted to pull it back, like Sera had done to me, but I’m sure I would have broken something on this horrible twig of a woman. Sam leapt up and jammed his thumb to her Cuff, and I let go. The conversation ended abruptly.

She sued us, of course—$1,700 worth. The bill showed up at home. Mrs. Nince also managed to make $3,108.88 off the words modish and Silent Freak, pushing us to within $80 of Collection.

FIND ME: $11.98

I sat in Falxo Park alone, at the spot where my stage had been. Sam offered to stay with me and sit in silence while I thought, but I knew he was in no mood for staying put. I sent him off with a flick of my eyes, secretly hoping he could think up some better plan than the one I’d gotten myself into.

When he was gone, my speech popped up on my Cuff. Keene Inc. wanted it read now? Was it just appearing randomly? What if I read it in the park, to an audience of no one? Would Butchers & Rog back down?

Unlikely. It was too late for that. I ran my finger on the glossy surface of my Cuff, thinking about how few objects in my world were smooth.

To my right, one of the faux Parisian shops was being reprinted, layer by layer. All these plastic buildings were rough to the touch, built upon each other, with strata that flared and splayed in thin, coarse lines. It was possible to smooth these walls out with a little skill and a hot, iron-like device from EvenMelt™, but that process was Patented and expensive—and looking closely at details was considered bad form.

The speech glowed on my arm. I flipped it away, embarrassed by my weakness. An Ad popped up in its place with a trill. Steadler’s™ Inks. More flavor-nutrition in every cartridge. I could flip it away, but it would only come right back, like a boomerang, with a message asking if I wanted to opt out. The tap was 10¢, but the amount made no difference. I wasn’t going to break my silence for it.

I felt weird, keeping my voice still, like I was playacting or lying. I hadn’t thought about what would happen after I went silent. Before, I would talk to myself when I was alone. I would work out my thoughts, or just mutter pretty words to myself. Regret crept up the back of my throat, and I had to remind myself that even if I hadn’t gone silent, I didn’t have the money to talk to myself anymore. Even if I hadn’t gone totally silent, I still would not be free to say much more.

I let the Ad sit, glowing, insistent, using me as a mini-billboard for as long as Steadler’s™ wanted to pay. Around me, the Ad screens had quietly filled with the same message, but lit dimly, like they were at half power. The park was awash in a sad blue glow, which suited my mood.

My Cuff felt warm. I pressed a finger to the edge near my wrist, realizing that I might never again feel the skin underneath. The Cuff’s warmth troubled me. It was not unheard of for NanoLion™ batteries to malfunction and go white-hot in a Cuff. If that happened, I’d lose my arm—and probably my life. Would I scream? Would it matter?

Perhaps sensing my blackening temper, the Ad on my arm finally winked away. The screens around me shut down, and the park darkened.

A short time later, a thick group of golden-haired teenage boys ambled by. They were enormous, fat-legged specimens of wealth and privilege. They glanced at me and walked on like they had stepped in dog feces. I lowered my head and hid my face. I didn’t want another confrontation.

Screens burst to life around them, flooding the path before them in bright, sunny colors. Ads addressed them loudly by name. Parker. Madroy. Thad. The Ads scrambled after them, like dogs desperate for a master’s attention, moving from screen to screen. Moon Mints™ invited them to sit in the park, showing them fatter, more pleasant-looking versions of themselves sitting in the park in golden light, laughing and surrounded by skinny, big-breasted girls far prettier than me.

Please no, I thought.

They heaved themselves down the street, waving off the Ads like flies. They couldn’t be bothered. One of them cupped his hands around his mouth and yelled back at me. “Sluk!” That was all the effort he could expend.

My Cuff popped to life again. Are you a Sluk? Take the Cosmo™ Quiz!

I kept my head down. The Ad faded quickly. Then I heard a different voice, this one quiet and gentle.

“I have things to tell you,” the voice whispered.

I looked up. Beecher’s grandmother was standing right in front of me. She was smaller and more stooped than I remembered. She wore a stiff black dress with sleeves so long they covered her hands. It looked ancient. She looked so sad, and I had the urge to tell her how sorry I was.

“Find me,” she said in a low, quavering voice. Her lips barely moved. Her head was low.

She shuffled away, back out of the park, and stepped onto the bridge with a heavy sigh. Find her? Did she want me to follow now? Why didn’t she just say what she wanted to say? Was she on the edge of Collection, too?

She moved to the side of the bridge opposite where Beecher had jumped, and then made her way over the curve. Anger suddenly twisted through me. Was she toying with me? Hadn’t I done enough for her? If Beecher hadn’t jumped, I don’t think any of this would have happened.

I wasn’t going to follow her. I wasn’t going to find her, either. If what she wanted to say was so important, she could find me.

SILENTS: $12.99

Nancee’s Last Day ceremony was moved to Pride’s Corner, a small, empty square of land not far from Mrs. Micharnd’s gymnastic academy. It was a “waker,” because Nancee had been born at 4:12 a.m. and Mrs. Harris refused to apply for a shifting permit to schedule the ceremony at a more reasonable hour.

“Maybe we’ll see a Placer,” Sam said, scanning the rooftops as we walked. He wasn’t supposed to come, technically, but he said he wanted to walk with me. Even if I had been speaking, though, I wouldn’t spoil his enthusiasm by pointing out that the Placers would have come through long before. They would have to know Nancee’s schedule, to make her Last Day Placements and set her Brand. But Sam enjoyed looking out for them too much for me to ruin it. I’d already ruined enough.