Полная версия

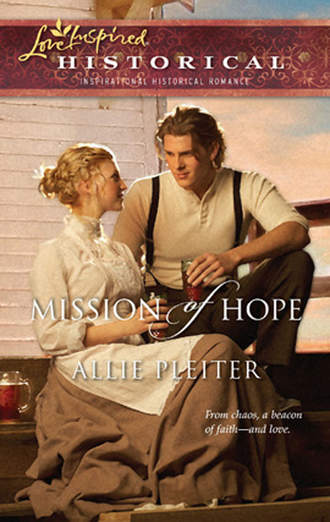

Mission of Hope

“I think you’ll find Major Simon a most extraordinary fellow.” Reverend Bauers walked over to a large sack Quinn only just then realized sat on a table in the center of the room. “With some very considerable resources.” He pulled open the drawstring and tilted the top for Quinn to peer inside.

The sack held half of what had been on his list. On Nora’s list, that is. Bandages, iodine, salt, a few tins of meat, needles and thread and half a dozen other various supplies. Major Simon went up a few notches in Quinn’s book, to be sure. More than a few.

“Where’d you get all that?”

“No need for you to know,” Simon said slyly.

“You stole it. Why else would you answer like that?”

“Would you take it no matter where it came from?”

“I’m smarter than that. I don’t know you, even if Reverend Bauers does.”

“They were ‘procured,’ perhaps, or more precisely, ‘diverted,’ but ready for you to put to good use.” Simon pulled the string shut, placing the sack into a crate that sat under the table. “And no, you don’t know me. Yet.”

“The major has arranged a discreet drop-off point,” Bauers said, clearly enjoying the adventure of it all. With that look in his eye, Quinn could easily imagine the days when Reverend Bauers had been the Black Bandit’s trusted accomplice. He seemed delighted to step into those shoes again. “You’re to return tonight and get it back to camp by…well…whatever means you find necessary.”

His first mission. It hummed through Quinn’s veins. Suddenly, he couldn’t get the Bandit’s old gray shirt on fast enough. He longed to strap on the sword and take the world by storm. Now.

“You have a fire in your eye, Freeman,” Major Simon said to him. “I’ve found our friend the reverend is rarely wrong on such things. But you’ll need far more than good intentions if you really want to do what you say. You’ll need training and cunning and several very particular skills. Skills I’ve offered to teach you. But you’ll have to be both patient and discreet.”

“I am.”

“You don’t strike me as patient in the least.”

“Would you be patient if your family didn’t have enough to eat or a real roof over their heads?”

Simon chuckled and clapped Quinn hard on the back. “Bold as brass. You’re right, Bauers, he’s just the man for the job. If he doesn’t get himself killed first.”

“You’ve no idea where all this came from?” Nora asked as she peered at the supplies that had appeared overnight at the Freeman shack.

Mrs. Freeman squinted at the cut on Sam’s foot, paused, and then dabbed it with a bit more iodine. “None at all,” she said over the resulting protests from Sam. “Quinn said he’d put the list up on a fence post across the street last night, asking for help. That’s all we know.” She turned to the boy. “Hush, lad, it’ll hurt far more than that if it don’t heal properly.” Her words were harsh, but her eyes were kind.

“It is amazing, isn’t it?” Nora examined the items again, grateful her father had allowed her to come over to Dolores Park to inspect this surprise package—provided, of course, that she was properly escorted, which wasn’t at all an unpleasant requirement. Nora turned over the tins of meats, looking for any clue. She’d shown the list to several people, and obviously someone else had now seen the list, but still no one seemed to know who’d found the rare items and delivered them to camp. It was a feat. As common as the items were, Nora could only manage to scare up two needles and three spools of thread. Before the earthquake, it might have taken her all of fifteen minutes to secure the entire list. How scarce life’s necessities had become.

“You’d best listen to my ma,” Quinn said, planting himself down on the chest next to a squirming Sam, whose bottom lip threatened tears at any moment. “You strike me as a smart lad. And a brave one. We’ll need you fit and strong to help out. You’ll be no use to me limping around like a goat, now will you?”

“I’ll need you to escort me,” Nora whispered to Sam, grinning. “I shouldn’t trouble Mr. Freeman much longer. He’s a busy man and he’s likely to tire of leading me to and fro.”

Quinn applied a mock frown, but his eyes told a far different story. While he’d refused her any details, she knew he’d gone to great lengths to meet the two o’clock mail run yesterday. When they were late because one of the cart’s finicky wheels had jammed, she’d found him practically pacing the street in a state she could only describe as panic. And while he’d walked calmly—perhaps it wasn’t too much of an exaggeration to say he swaggered slightly—back to the edge of the camp, she’d noticed he broke into a flat-out run once he turned the corner. Yes, sir, Quinn Freeman was very late for something yesterday, and she could not deny what his tarrying had done to that sparkling spot just above her stomach. He looked at her as if she were the best part of his day, and she was not at all certain she hid her own pleasure at seeing him.

“She’s far too much work, this one,” Quinn said. The sour notes in his voice were no match at all for the spark in his eyes. “Take her off my hands as fast as you can, man.” He ruffled Sam’s moppish hair.

Mrs. Freeman gave the quickest of glances back and forth between her son and Nora. “When the foot’s ready, and not a moment before. Iodine and bandages are too rare to go wasting with foolishness. Put that sock back on, young man, and mind you stay out of the dust as best you can. Come back tomorrow and I’ll have a look at it again.”

“Yep,” said Sam, sliding off the trunk.

Quinn snagged the boy’s elbow as he went to leave. “Yes, ma’am, and say thank you.”

“Thanks, ma’am.” Sam punctuated his attempt at manners by wiping his nose on his sleeve.

Mrs. Freeman moaned. “I’m climbin’ uphill both ways to keep anything clean here.” She rubbed the back of her neck with her hand and sighed. “What I wouldn’t give for a true sink and a clean set of sheets.”

Quinn gave his mother a quick peck on the cheek. “You’ve worked wonders as it is, Ma.” He pointed to the stock of supplies. “And somebody’s taken notice.”

“And wouldn’t I like to know who?” his mother said, smiling. “And what else they’ve got. Father Christmas coming in July. Who’d have thought?” She wiped her hands on her apron and began loading the supplies back into the trunk. “Get her back now, Quinn, before her father starts to worrying about where she is.”

Quinn shrugged his coat back on as they walked. “So your father’s office didn’t deliver that package? I thought surely you’d done it. You had the list, after all.”

“So did you,” Nora replied. “And you posted it. Someone with the things must have seen the one you tacked up. Still, what showed up didn’t really match up to the list we’d made.”

“It’s a mystery, to be sure.” He went to do the button on his coat, found no button to do, and gave out a little hrrmph as he was forced to let it hang open. “I may have to beg Ma for a little of that thread, won’t I?” They walked on, and Nora made a note to dig through her father’s coats for a spare button tonight. “Everyone needs everything, it seems,” Quinn sighed. “Reverend Bauers at Grace House can be a resourceful man, but he needs all of those things as much as we do, if not more.”

“I’ve heard stories about Grace House. Is it still standing?

“It is,” Quinn replied. “The building next door fell to the ground, but Grace House is mostly fine.”

Nora let out a long sigh. “It’s hard not to wonder how He’s let all this happen and why. I can’t get my mind around anything that makes sense, no matter how many prayers I say.”

“No sense to be made, if you ask me. Some things just are. You could stand around all day trying to figure out why, and it still won’t find you dinner or get your house rebuilt. It’s not the whys we need to worry about now, Miss Longstreet, it’s the hows that matter most.”

“How, then, do you think those things found their way to your mother?”

He stuffed his hands in his pockets and shrugged his shoulders. “Don’t rightly know.”

“Someone, somewhere, has played the hero. I think it’s perfectly grand. I hope everyone hears about it and twenty other people do the same. What a wonderful thing that would be, don’t you think?”

Quinn laughed. He had a very delightful, forthright laugh. “I think you’re getting ahead of yourself, miss. It’s not smart to make so much of one good deed.”

“One good deed like a teeter-totter? Oh, I think you know the power of one good deed far more than you let on.” She didn’t hide the broad smile that crept up from somewhere near her heart.

“Grace House does the important work, not me. But even they’re busting under the load right now, or so Reverend Bauers says. He’s got a few benefactors who can help out, you know, friends in high places and all, but not nearly enough.”

Why hadn’t she thought of it before now? “I can help with that.”

He raised an eyebrow. “I think you’re helping as much as you can now. Your pa’ll be sore at your being gone as long as you have, if not worse.”

“No, I mean with the benefactors. I know someone who can help. We had a wealthy woman named Mrs. Hastings to tea at the house the other day. She’s wanted to see the ruined city but her husband won’t let her come any farther than our house.” Nora looked at Quinn. “What if we could get Mrs. Hastings to tour Grace House? Surely her husband couldn’t object to something like that? Then she could meet people. She could meet Reverend Bauers. I’ve heard so much about him, even I’d like to meet Reverend Bauers. It’s the perfect solution.”

Quinn stopped walking and looked at her. “You’ve never met Reverend Bauers?”

He made it sound as if her social upbringing lacked a crucial element. “Well, of course I’ve shaken his hand at some city ceremony at some time or another, but I don’t really know him. I only know of him. Papa knows him, I think, but not socially.”

Those words came out wrong. As if people like Papa didn’t socialize with people like Reverend Bauers. It was true, in some ways, but not in the way her words made it sound. Quinn had noticed. He stood up straighter, started walking again, and the set of his jaw hardened just enough for her to notice.

Nora reached out and caught his elbow. “I didn’t mean it like that.”

“No one ever does.” The edge in his voice betrayed the wound her words had caused.

“No, really. It was a horrid way to put it. I just meant…” What did she just mean? She’d said it without thinking, without consideration, of what Mama would have called “their differences in station.” Why consider some great foolish gulf between them—especially now, when all that seemed to matter so very little? She dropped her hand. “I don’t know what I meant. But I’ve not met Reverend Bauers and I would very much like to. And I want to help. I believe Mrs. Hastings will want to help, too, if we can show her Grace House. Please. I know she will.”

“If she honestly wants to help, and not just gawk at other folks’ hardship. I’ve seen those types. Riding in carriages around the edge of our camp with hankies pressed to their noses. As if we’re all some odd entertainment.”

“Mrs. Hastings can be a bit stuffy, but I think she truly does want to help. She just doesn’t know how. Or maybe just where to start. I know something good would come of it if we could just make the arrangements.” Suddenly, it had become the most urgent thing in the world. Something large and important she could do to make things better. And surely, once she’d been to Grace House with Mrs. Hastings, Papa might let her do more than just sit around and wind bandages. Mrs. Hastings had loads of friends with all sorts of connections. Even Mama would be delighted to work on projects with someone of the Hastingses’ stature. It was the most perfect of ideas.

Quinn’s expression softened. “I’ll see what I can do.”

Chapter Seven

“You’ve left your side unprotected,” Major Simon warned. “I could have run you through four minutes ago.”

“So you said,” Quinn panted as he wiped the sweat from his forehead with his sleeve. Major Simon was proving to be a merciless teacher. Just a moment ago he’d planted the tip of his sword over Quinn’s pounding heart and declared with an annoying calm that in a real duel, Quinn’s life would have come to an abrupt end. Something in his eyes made Quinn believe he could do it. Part of him suspected the major had taken more than one life—in battle or otherwise—but the wiser part of him decided he didn’t really want to know.

“Die? Right here?” Quinn challenged as he regained his footing. It was useful to discover he didn’t at all like being on what Mr. Covington had once called “the business end” of a sword. Quinn vowed to remember the unpleasant sensation of having a blade planted gingerly on his chest—and vowed it would never happen again.

“Hardly sporting of me, I know,” Simon pronounced as he flicked the blade away.

“Speaking of sporting…” With a swift move, Quinn skidded down and forward, making sure his tattered boot collided with Major Simon’s foot, sending the stocky officer off balance. With another kick, he knocked Simon’s remaining knee sideways so that the major came down to the floor in a crash of weapons.

He shot Quinn a nasty look, then laughed. “One does not kick in fencing!”

Quinn held out a hand, telling himself it would be unsporting to enjoy the moment but enjoying it immensely. Simon had kept the upper hand for most of the hour, anyway. “Were we fencing?”

Simon took Quinn’s extended hand and pulled himself to his feet. “That was entirely uncalled for. And downright clever. An old general of mine used to say that the best use for rules was knowing when to break them.” He slid the foil into the holder at his hip. “I dare say it’s a lesson you already know.”

“Life can be a good teacher of some things.”

“And not others. You kicked me because you were angry, not because it was a good strategy. It worked this time. It won’t the next.” He pointed a finger at Quinn as he pulled a handkerchief from his pocket. “You fight with too much emotion, Freeman. We’ll have to work to cool that temper of yours. Give me your hand.” He held out his hand to shake Quinn’s.

Matthew Covington had insisted they shake hands at the end of every fencing lesson or duel as well. Quinn pulled off his glove and held out his hand.

At which point Simon grabbed it, held it, and before Quinn could even blink, had produced a short dagger from his boot and dragged it sharply down Quinn’s forearm.

“Ouch!” Quinn yelled as a thick line of blood pooled where Simon had scratched—no, sliced him. He just barely bit back a retort that would have made Ma’s ears burn. “What the…”

“No broken rule goes without consequences. Every knife hurts, especially the one you didn’t see coming.” Simon handed Quinn the handkerchief. “Next time you face me, you’ll think twice. A small price to pay for wisdom.”

Quinn stood, staring at the man, unable to piece together the gentleman with the savage who’d just calmly cut him.

“It’s but a scratch,” Simon said, “and the first lesson I give all my best students.”

“Some compliment,” Quinn muttered. “What will happen to me if you really like me?”

Simon looked him straight in the eye. “You’ll live.”

As he stood in Reverend Bauers’s study that afternoon, wincing at the excess of iodine the pastor dabbed over his forearm, Quinn recounted the major’s painful lesson.

“I can’t say I care for his methods, but Simon makes an important point.” The reverend smiled. “No pun intended.”

Quinn thought about the tip of Simon’s foil skewered into his chest. “He’s a wild sort, he is. Dangerous.”

“No, I think that Major Simon is just a man aware of how dangerous a game we aim to play here. The moment you forget yourself in the name of playing hero, that’s the moment any fool could come out of the shadows and take you.” He put a clean bandage over the wound. “How’ll you explain that cut to your ma?”

“I’ll worry about that later.” Quinn looked at the reverend. “Are you saying I shouldn’t be doing this now? Changing your mind?”

“Not at all. I’m only saying we can’t be too careful. ‘Wise as serpents,’ the Bible says. Taking on evil—even with the best of intentions—is always a dangerous endeavor.”

Quinn muttered a thing or two about the snakelike nature of a certain army major as Bauers bound off the bandage. The wound smarted for a dozen different reasons, only half of which could be attributed to Reverend Bauers’s enthusiastic doctoring.

“Think of it as a repayment,” Bauers said, raising a disapproving eyebrow to Quinn’s muttered insults. “You do remember the very nasty gash you gave Mr. Covington on your first meeting? The cut you lads gave Matthew was much bigger and twice as deep. All for his noble effort to try and stop you two hooligans from stealing from Grace House. Why, I stitched up his arm in the very next room. After twenty-odd years, has a bit of balance to it, don’t you think?”

“No, I don’t.” Quinn flexed his arm. “And this hurts.”

“Good. Now—” Bauers changed his tone as he put the medical supplies back in their box “—have you given thought to the message system?”

“It’ll go up just before dark tonight,” Quinn replied. “If I’ve got both arms to use by then. I found the wood yesterday, and with a bit of help I can have the post up in an hour. Right across the street from where the mail cart comes in.”

Bauers smiled. “By the mail cart. What an extraordinary coincidence.”

When the mail cart pulled up the next day, Nora noticed a large square post had been erected across the street. A sort of column made from pieced-together planks of wood now stood in the passageway between two shacks. People crowded around it, and it was a minute or so before Nora realized small pieces of paper and scraps of wood and material were stuck to the thing.

She’d heard about a fountain downtown that had become a message board of sorts. People fastened messages or notices or sad notes like “Can’t find Erin Gray since Tuesday” on Lotta’s fountain at Kearny and Market streets. It had become a vital communication place, a gathering spot for the lost and those who had been found. Logistically and emotionally the center point of town. Someone—someone very clever—had thought to do the same here.

When Nora looked out over the crowd, her suspicions proved correct, for her one raised eyebrow of silent inquiry was met with Quinn Freeman’s grinning nod.

“The mail can’t all be headed out of town,” he said when he ambled across the street. “Folks here need to send messages of a smaller sort, too. Took all of an hour, once I found the wood.”

She noticed he had a bandage on his right forearm. “It took a bit more than that, it seems,” she said, pointing to the wound. “That wasn’t there yesterday.”

From behind her at the mail cart, Nora heard her father make a grumbling sort of noise, as if he wasn’t much fond of his daughter noticing the state of some man’s forearms. When she turned, he shot a look of warning between them, as if telling her to stay on the cart while he climbed down to hoist another mailbag off.

“A fencing injury,” he said, pleased at her concern. “I won the duel, anyway.”

What a wit he had. “Now, Mr. Freeman, what sort of man has time for fencing these days?”

“You’d be surprised.” His eyes fairly sparkled. He had the most extraordinary vitality about him. An energy, an inner source of power that stood out like the noonday sun in such a sea of weary souls. And when he looked at her like that, a spark of that power lit up inside her own soul. It was at once thrilling and dangerous.

Nora hid the blush she felt creeping up her face by changing subjects. “How is Sam?” she said brightly, fiddling with a stack of mail. “All healed?”

“Soon enough. He was asking to come over here this morning, but Ma held him off one more day. Fairly bursting to run around, he is. Ma threatened to put him on a leash yesterday afternoon after you left.”

“How resilient children are,” she sighed, sitting down on the edge of the cart. “I think they’ve fared the best of all of us.” Mrs. Hastings’s visit had cheered Mother and Aunt Julia for a little while after, but the dark melancholy had returned within a few days.

“We do fine. Well, as much as we can. You should come over and look at the post. There’s happy news there, as well as the sad news.” He pointed toward the wooden column and extended a hand to help her out of the cart.

Her father didn’t look pleased, but neither did he voice an open objection—that would have to do for now. Nora took Quinn’s hand, forgetting she’d removed her gloves, for it was nearly impossible to handle stacks of paper and the other odd forms of mail with gloves on. He clasped her hand, stunning her with the touch of his rough palms. They were working hands, large and calloused, yet strong and steady. Warm. Something unnamed shot through her, something far more alarming than what his eyes had done. Nora tried to brush it off as something from a dime-store novel, a juvenile thrill, but it felt so…important.

A touch. Quinn Freeman had touched her. Papa was undoubtedly cross, even though it was something as genteel as helping her out of the wagon. Still, she wasn’t the least bit sorry she wasn’t wearing gloves.

He winced, and she realized he had helped her out of the wagon with his injured arm. “Goodness,” she said, “You really are injured there.”

“Only just,” he said, still smiling. “I’ll be fine.” She knew by the way he looked at her that he was as aware of their touch as she was. He held her hand for a fraction of a second longer than was necessary before letting it go and motioning toward the post. She felt that tiny linger—a trembling sensation in her hand—as if her palm would somehow be able to retain the feeling. Nora felt as if she would look at her hand an hour from now and find it physically changed.

She saw, out of the corner of her eye, that Quinn ran his thumb along the tip of each finger. He felt it, too. They walked quietly toward the post, each of them a little bit stunned, pretending at normalcy when nothing at all seemed normal.

Notes of every description, on every kind of material, had begun to cover the post, tacked and pinned or stuffed into cracks. One small corner of a newspaper held the message “Looking for Robert Morris.” Another read “A.D.—I’m fine—M.T.” One heart-wrenching note read “Josiah Edwards born Tuesday morning.” Nora hadn’t even thought about the fact that babies were still arriving. It was cheering to know life went on, but what sort of anguish gripped a mother bringing a precious new life into the wake of catastrophe?

Quinn noticed her eyes on the announcement and nodded at her. “I saw little Josiah yesterday morning. Fine and healthy and hungry as any baby ever was. He’s hurting for a few necessities, but I gather he’ll make out just fine.”

Nora thought of all the soft, clean pampering that surrounded the last baby she’d seen. Babies should never know hardship—it was just wrong. “What’s he missing?”

Adjusting his hat, Quinn pursed his lips in thought. “The usual things—diapers, cloths, jumpers and such. Soap, too, I suppose.” Getting an idea, he began to walk around the post, one hand roaming over the fluttering papers. “Oh, here’s one. ‘Baby arrived. Need sheets, shirts, cloths and pins.’ You know, that sort of thing. Ma found a clean pillowcase they cut down for Josiah to wear and a pair of little socks from a doll somewhere, so things find their way.”

Nora began to look all over the post now, scanning for any requests like the baby’s. There were half a dozen, maybe more, and the post had only been up one day. “I want to write these down, like I did the others. Surely we can find some of these things.”

“Could you make me a copy, like you did before?”

“Of course I could. Do you have any ideas where we might find some of this?” The “we” had slipped out of her mouth unawares.

“I’ve a few thoughts,” he replied. His eyes glowed again, and Nora felt surely Papa would storm across the street this very second and plant her back on the cart.