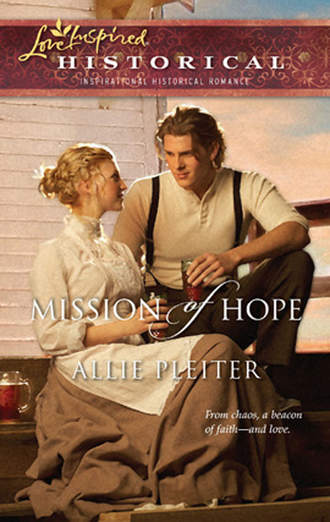

Полная версия

Mission of Hope

“My father would agree heartily. He’ll probably be rather sore at me for trying. I hadn’t realized…thank you again. First the locket, and now this. Surely there’s some way to thank you.”

He smiled the engaging grin he’d shown her back at the rally. His eyes were a light brown, an almost golden color that picked up the straw shades of his hair. He had a strong, square jaw that framed his easy grin—the sort of face at home with a frequent smile. “Like I said, Miss Longstreet, I was happy to see something find its way home.” The sadness in the edge of his voice—the sadness that caught the edge of so many voices all around her—undercut the cheer of his words. “But there is something I’d like to show you. Something you ought to see before you leave with Ollie’s version of how things are in here.”

“Do you live nearby?” She realized what a ludicrous question that was, as if he had a house just up the street instead of a shack somewhere in this makeshift camp.

He tucked his hands into his pockets and nodded over his left shoulder. “Two rows down. The charming cottage on the left.” When Nora blushed, feeling like an insensitive clod for asking such a useless question, he merely chuckled. “It’s okay, really. I’ve seen worse. My uncle Mike says we might get back into a house next month. Just come see this and I’ll walk you back across the street before your papa begins to worry.”

He led Nora through one more row of shacks to where a cluster of children gathered. The gaggle of tots surged toward Quinn when they saw him, parting the crowd to reveal a rough-hewn teeter-totter pieced together out of scrap and an old barrel. She knew, instantly, that the makeshift toy had been Quinn’s doing.

“Mister Kin, Mister Kin!” a chubby blond-haired girl greeted. Nora guessed it to be her approximation of Mr. Freeman’s given name. “It works!”

Quinn hunched down and tenderly touched the tot’s nose. “Told you it would.” Nora smiled. How long had it been since she had heard children’s laughter?

The girl giggled. “You’re smart.”

“Only just. Go ahead and take another turn, then. It’ll be time to get on back to your ma soon, anyway.”

Nora stood awed for a moment. Quinn Freeman had handed her the smallest patch of happiness, but it did the trick. “Thank you.” She looked up at him, for he was a good foot taller than she if only a few years older, and thought that he was indeed clever to recognize a slapped-together toy would do so much good. “I did need to see this—you were right.”

“Most people are afraid to really build anything here, thinking it’ll make it feel like we’ll be here forever, but even I know lads with nothing to do usually find something bad to fill their time.”

“You’ll be here another month?” Many families were talking of pulling up stakes and starting over somewhere else just as soon as circumstances would allow. Others refused to even think past their next meal.

“That’s my guess. Don’t pay much to peer too far into the future these days. God’s got His hands full in the present, I’d say.”

“He does.” And he talks about God. In a calm way. Many people—her own family pastor Reverend Mansfield included—were shouting about the awful judgment God had “sent down” upon the sinful city of San Francisco. It wasn’t so hard a thought to hold. With dust and destruction everywhere, it was easy to wonder if the Lord Almighty hadn’t indeed turned His head away.

By this time they’d reached the mail wagon, and Papa was standing with a sour and alarmed look on his face. “Thank heavens you’re all right. Just what do you think…?”

“I’ve seen her back safely, Mr. Longstreet, and told her not to venture over here like that again,” Quinn cut in.

“Papa, this is Mr. Freeman. The man who returned Annette’s locket. Now you can thank him in person.”

The announcement took the wind out of Papa’s scorn. Her father stepped down off the mail wagon and extended a hand to Quinn. “Seems I owe you.”

The two men shook hands. “You don’t owe me a thing. I was glad to help.”

Papa looked at Nora. “Don’t you go needing help again. I’ll not let you come back if you wander off like that again. It’s only by God’s grace that Mr. Freeman was here to keep you from any trouble.”

“Grace indeed,” Quinn said, shooting a sideways smile at Nora as he tipped his hat at Papa. “Don’t let it happen again, Miss Longstreet.” As he turned, he added quietly over Nora’s shoulder, “At least not until tomorrow around two.”

Nora climbed back on the wagon to join her father. Perhaps the mail would not be so perfunctory from now on.

Chapter Three

Ah, but she was a beauty.

Quinn stood mesmerized by the way she held her ground. Tall and proud, with defiant lines he wanted to catch from every angle.

Quinn was vaguely aware of an elbow to his ribs. “Nephew, ya look foolish just standing there like that.”

Rough hands grabbed his face on both sides and pulled his gaze to the dusty, whiskered sight of his uncle Michael. “There’s something wrong with you, man. It ain’t natural, the way you look at buildings.”

“Architecture. It’s called architecture. I’d give anything to study.”

Uncle Mike snorted. “You need a wife.”

Quinn shifted his sore feet as his mind catapulted back to the rows of tiny black buttons that ran up the sides of Nora Longstreet’s boots. He’d stared then, too, liking their lines as much if not more. “I need to learn,” he said impatiently to his uncle, who simply rolled his eyes at the speech he’d heard every day even before the earthquake. “Apprentice an architect. Only there’s no time to learn anymore. We need loads of builders, but we need them now.” Everything took so much time these days. Lord Jesus, You know I’m thankful to be alive, but this bread line feels two thousand miles long. I’m in no mood to learn no more patience, if You please. He felt he’d die if he wasn’t back at the camp edge by two. He had to see her again. Had to see that dented locket that he just knew would be polished up and hanging around her neck. He’d miss half a week’s worth of bread to make sure he caught that sight—even if it meant he’d catch a whole lot more from his ma for returning without bread.

By the time the sun was high in the sky and the police officer on the corner said it was one-fifteen, Quinn still was looking at forty or so people in line in front of him. Without so much as an explanation, Quinn nudged his uncle and said, “I’m off.”

“And just what do you think you’re doin’?” the man balked as Quinn strode off in the direction of home, his feet no longer feeling the holes that burst through his shoes yesterday.

“I ain’t sure yet,” Quinn replied with a grin, tipping his hat as his uncle stood slack-jawed, “but I’ll let you know.”

Nora sat beside her father in the mail cart, her heart thumping like the hooves of the horse in front of them. Since the earthquake, she’d barely looked forward to anything or been excited about anything.

She wanted to see him. To feel that tug on her pulse when he caught sight of her. He seemed so happy to see her. She knew, just by the tilt of his head, that she brightened his day. There was a deep satisfaction in that; something that went beyond filling a hungry belly. Still, that hadn’t stopped her from bringing a loaf of bread she’d charmed out of the cook this morning.

He was a very clever man. He stood on the other side of the street, far enough from the cart to be unobtrusive, near enough to make sure she caught sight of him almost immediately. His eyes held the same fixation they had at the ceremony, and Nora felt a bit on display as she went about her duties.

He watched her. His gaze was almost a physical sensation, like heat or wind. He made no attempts to hide his attentions, and the frank honesty of his stare rattled her a bit, but not the way that man Ollie’s stare had. She might be all of twenty-two, but Nora had lived long enough to judge when a man’s intentions were not what they should be. Simply put, Quinn looked exceedingly glad to see her again. And there was something wonderful about that.

“You’ll stay by the cart today,” Quinn said, walking across the street when the line finally thinned out. “Mind your papa and all.”

“I should,” she admitted. “However, I would like very much to see the teeter-totter again. It seemed a very clever thing to do, and I wonder if there aren’t some things back at my aunt’s house that we could add to your contraption.”

A bright grin swept over his face. “My contraption. I like that a far sight better than that thing Quinn built.” He pushed his hat back on his head as he looked up at her, squinting in the sunlight. It gave Nora an excuse to settle herself down on the cart, bringing her closer to eye level with the man. “A contraption sounds important. I’ll have to build another just to say I am a man of contraptions.”

They held each other’s gaze for a moment, and Nora felt it rush down her spine. It was powerful stuff these days to see someone happy—they’d barely left misery behind, and there was so much yet to endure ahead of them. She’d taken the streetcars completely for granted before. Now, everyone’s shoes—and feet—had suffered far too much walking. She imagined his smile would be striking anywhere, but here and now, it was dashing.

“Still,” he said, “it’s best we don’t wander off today. I wouldn’t want your papa thinking poorly of me.”

“Oh, I’m sure he couldn’t do that.” Nora fingered the locket now fastened around her neck. Something flickered in his eyes when she touched it. “You brought me back Annette’s locket, and that was a fine thing to do.”

“The pleasure’s mostly mine, Miss. I think it made me as happy as it made you. And good news is as hard to come by as good food these days.”

“Oh,” Nora shot to her feet, remembering the loaf of bread tucked away behind her. “That reminds me. I know you said you didn’t need a reward, but I just didn’t feel right without doing something.” She pulled out the loaf, wrapped in an old napkin. “Cook makes the best bread, even missing half her kitchen.” She held it out.

“Glory,” Quinn said, his grin getting wider, “You can’t imagine how glad I am to see a loaf of bread. Especially today.”

“Aren’t you able to get any?”

She thought she saw him wink. “That’s a long story. Just know you couldn’t have picked a better day to give me a loaf of bread.”

That felt simply grand, to know she’d done something he appreciated so much. “I’m glad, then. We’re even.”

“Hardly,” he said, settling his hat down on to his head again. “I’m still ahead of you, Miss Longstreet. By miles.” He bent his nose to the bread and sniffed. “I’d best get this home before it gets all shared away. Thank you, Miss Longstreet. Thank you very much.”

“My pleasure,” Nora said, meaning it. Taking a deep breath, she bolstered her courage and offered, “Tomorrow?”

“Absolutely.”

The only sad thing about the entire exchange was that three months ago, Nora would have rushed home to tell every little detail to Annette. Today, she didn’t mind the trickle of mail customers that still came to the wagon, for there was only Mama waiting at home. Nora laid her hand across the locket, hoping her thoughts could soar to where Annette could hear them. Is heaven lovely? I miss you so much.

Reverend Bauers tried to lift the large dusty box, but couldn’t budge the heavy load at his advanced years. He huffed, batted at the resulting cloud of dust that had wafted up around him and threw Quinn a disgusted glance. “I’m too old for this.”

Quinn wiped his brow with his shirtsleeve. It was stale and dusty down here in the Grace Mission House basement, and he’d already had a long day’s work, but he’d be hanged if he’d let Reverend Bauers attempt cleaning up the rubble on his own. The man was nearly eighty, and although he showed little signs of slowing down his service to God, his body occasionally reminded him of the truth in “the spirit is willing but the flesh is weak.”

“Didn’t I just get through telling you the very same thing? Reverend, I don’t think when God spared you and Grace House through the earthquake and the fire that He did it all to have you collapse in the basement. You’ve got to slow down. You’ll do no good to anyone if you hurt yourself.”

His long and fast friendship with the pastor—since boyhood, going on twenty years now—had given him leave to speak freely with Reverend Bauers, but even Quinn knew when too far was too far. And even if the reverend’s insistence on ordering the Grace House basement was a bit misguided, Quinn wasn’t entirely sure he should be the soul to point it out. People reacted in funny ways to the overwhelming scale of destruction. His own ma bent over her tatting every night, even though Quinn was certain there’d be little use for lace in the coming months. Many people focused on ordering one little segment of their lives, because they could and because so much of the rest of their lives was spinning in chaos.

“I can’t seem to stay away,” Reverend Bauers said, giving a look that was part understanding, part defiance. “I keep getting nudges to tidy up down here, and you know I make it a policy not to ignore nudges.” Reverend Bauers was forever getting “nudges” from God. And Quinn believed God did indeed nudge the portly old German—he’d seen far too much evidence of it to dismiss the man’s connection with The Almighty. Only no one else ever just got “nudged.” God seemed to be shouting at everyone else—or so they said. People were talking everywhere about God’s judgment on San Francisco or claiming they’d heard God’s command to destroy the city—and/or rebuild it, depending on who you talked to.

Only, after twenty-six years, God had yet to nudge or shout at Quinn. Reverend Bauers was always going on about purpose and providence and such, and he’d so vehemently declared that God had spared Quinn for some great reason that Quinn mostly believed him. The reason just hadn’t shown itself yet, nor had any of God’s nudges.

Quinn sighed as Bauers slid yet another box out of his way, poking through the cluttered basement. “There must be something down here,” Bauers said, almost to himself. “Over there, perhaps.” He pointed to a stack of shelving that had toppled over in the far corner of the room and motioned for Quinn to clear a path.

It took nearly ten minutes, and Quinn was tempted to offer up a nudge of his own to God about how dinner might be soon, when suddenly Bauers went still.

Quinn looked up from the shelf he was righting to see the reverend staring intently at an upended chest. “Oh, my,” Bauers said in the most peculiar tone of voice. “Goodness. I hadn’t even remembered this was down here.”

“What?” Quinn cleared a path to it.

“That’s it, isn’t it? And there should be another one—a long, narrow one—right beside it somewhere.”

Quinn stared from Bauers to the pair of chests, his heart thumping as he recognized the shape of the long narrow box. He must have been, what, twelve? Surely not much older. He caught Bauers’s gaze, the old man’s eyes crinkling up when he read Quinn’s expression.

“Mr. Covington’s things.” Quinn began tearing through the boxes, bags and beams between him and the pair of chests. “Those are Mr. Covington’s…”

“No, man, not just Mr. Covington’s, and you know that. Those belong to the Bandit.”

Quinn had reached the chests, fingering the latch on the longer box. He remembered what was inside now. He remembered thinking that that sword and that whip were the most powerful weapons on earth. He blew the dust off the box and set it atop a crate. “Do you think it lasted?”

“I see no scorch marks or dents. I’d venture to say it’s in perfect shape.” He picked his way quickly through the room until he stood next to Quinn. “But we’ll not know a thing until you open it.”

Chapter Four

With a deep breath, Quinn undid the pair of latches on either side of the long wooden box. Inside, carefully nestled in their places on a bed of still amazingly blue velvet, lay a pair of swords. Even with the patina of twenty years, they gleamed in the basement’s faint light. “His swords,” Quinn remarked, not hiding his amazement. “The Bandit’s swords.”

Reverend Bauers’s hand came to rest on Quinn’s shoulder. “So many years. Such a long time ago—for both of us.”

Quinn could hear the smile in Reverend Bauers’s voice, sure it matched his own as he remembered the daring heroic feats of the Black Bandit that had once captured his young imagination. A dark hero who roamed the streets at night, offering aid to those who had none, supplying food to needy families, even sending money once to fix Grace House. The Black Bandit legend had woven its way into San Francisco’s history—everyone’s mother and grandmother had a Black Bandit story—but Quinn and the reverend were two of the only four people in the world who knew Matthew Covington had been the man behind the mask. He cocked his head in the clergyman’s direction. “Wouldn’t we like to have our Bandit back now, hmm?”

Quinn picked up the sword, turning it to catch the light. When he was twelve, this sword had seemed enormous. Too heavy and long for a slight boy. Time and trials had done their work on Quinn, however, and he was a tall man of considerable strength. He wondered, for a moment, if he remembered any of the moves Mr. Covington had taught him. “Do you remember that day, Reverend?”

There was no need to explain “that day.” Bauers would know Quinn was referring to the day he met—and marred—the noble English businessman. Bauers’s smile and nod confirmed his understanding. “Evidently, I’ve remembered it better than you. You, who have the most reason of all to remember that day.”

Quinn’s introduction to Matthew Covington had been, in fact, by injury. He’d taken a knife to Covington’s arm as the Englishman tried to stop a robbery. A crime Quinn and his buddy were attempting—stealing from Grace House. It was amusing, in a sad sort of way, to think they’d thought times hard enough to steal from a church back then. Those times were nothing compared to what they were now.

Still, Quinn was young, impressionable and desperate for decent food. His father’s love of the whiskey bottle hadn’t made for much of a steady home life. Trying to steal from Grace House Mission—an organization bent on helping his impoverished neighborhood—had been the low point of his life.

It had also been the turning point. Back in that garden, watching Matthew Covington bleed, Quinn had realized he had two choices in life: up or down. Dark or light. Hard or easy. And, when it came right down to it, destruction or redemption. That day Quinn chose to climb his way out of the mess his young life had become, and Reverend Bauers had been the first to recognize it. That troublesome day, and the tense ones that followed it, marked the beginning of Quinn’s unusually close relationship with the reverend. Uncle Mike had been known to say that Bauers was the real father Quinn never had; and it was true.

Quinn swung the sword in a gentle arc. It felt so light now. “Do you think he knows? Everything that’s happened here?”

Bauers smiled. “Matthew and Georgia wired money last week and asked that we wire back a list of needed supplies. His own son is fifteen now.”

Quinn tilted the sword again, admiring it. Even though Bauers had only been able to secure him a year or two of fencing lessons, he knew it was an outstanding weapon. It had a graceful balance and tremendous strength.

As wondrous as the sword was, it wasn’t the weapon most people associated with the Black Bandit. Catching Bauers’s eye, Quinn flipped open the second chest. There it lay, on top, carefully coiled; the Bandit’s leather whip. His mind wandered back to the summer afternoons where Quinn would swish a length of rope around the Grace House garden, pretending at the Bandit’s skill with his whip. Quinn lifted it carefully—it hadn’t survived the years as well as the swords. Bits of leather disintegrated with every flex, and the rich black braids were a stiff and crackled gray. He found himself afraid to uncoil it, simply moving it to the side to gain access to the rest of the chest’s contents. It contained exactly what he knew it would: a pair of black boots with a small silver B imbedded in each calf, a trio of dark gray shirts—voluminous, almost piratelike in appearance—and a black hat with the remnants of a white feather beside it.

And there, at the bottom of the chest, lay the mask. An ingenious thing, the Bandit’s mask was almost a leather helmet with a strip that could either come down over the eyes or fold up into the hat. Covington had let him try the mask on once, and the thing had nearly slid off his head. Quinn raised the mask into the light, inspecting it. It had held up much better than the whip, still surprisingly supple even after so much time. He couldn’t help but smile at the memory of the Bandit’s myriad of adventures. “Mr. Covington should have kept these.”

The reverend’s expression changed. “I don’t think that was the plan. He gave those to you. And Matthew Covington did everything for a very good reason.”

That made Quinn laugh. “I’ve not much use for a sword and whip, now do I? Although I could put the boots to good use.”

Reverend Bauers leaned his heavy frame against a dusty chest of drawers. “It makes one wonder.”

“What?”

“What else you could put to good use.”

It took Quinn a full ten seconds to gain the man’s meaning, at which point he dropped the mask. “You’re not serious.”

The sparkle in Reverend Bauers’s eye was unmistakable. “Why not?”

Quinn squared off at the man. “I’m a bit old for adventure stories. And times are a mite harder now.”

Bauers folded his arms across his chest. It was a gesture Quinn knew all too well, and he did not like the look of it.

“Matthew was close to your age when it all started. And it all started with a story.” He caught Quinn’s glare. “Stories are meant to be told. And retold.”

“I’m not Matthew Covington,” he said, because it needed saying. Covington was a clever, wealthy man who’d done remarkable things.

“No, Quinn. You’re you. Matthew knew that, too. What if you are exactly the man we need? Do you really think we’re down here digging in the basement for no reason at all?”

Quinn sank down on a crate. “I hardly think God brought me down to your cellar to ask me to be the Black Bandit.”

It was a long moment before Bauers answered simply, “How do you know?”

“Because it’s insane. I’ve barely enough food to eat, my shoes have twelve holes in them, the city’s barely getting through the day, I’ve no money, no influence and barely a spare hour to think.”

Bauers’s face split into a satisfied grin. “But you found enough time to help an old man go through his cellar. You found enough time to build those little ones that toy you told me about. You know what I always say—there’s always enough time to do God’s will.”

Even as the mail cart bounced its way a block from Aunt Julia’s house, Nora could tell something was happening. The house seemed almost bustling, with Mama and Aunt Julia scurrying around the yard and porch with a speed and energy Nora hadn’t seen in a while. A gracious table—or as gracious a table as one could manage these days—was set up on the porch.

Tea. Mama and Julia were setting out afternoon tea. And while afternoon tea had recently meant cups and saucers on mismatched plates with whatever crackers could be managed, this tea was different. It took a moment for Nora to realize what Mama and Aunt Julia were actually doing; they were entertaining.

“There you are,” said Mama hurriedly as the cart rattled its way into the drive. “Goodness, I thought you’d miss it altogether. Run upstairs, find whichever dress is the most clean and put it on. She’ll be here soon.”

“Who?” Nora and her father asked at the same time.

“Mrs. Hastings.”

“Dorothy Hastings? Here?” Papa asked. “I didn’t think she was still in town.”

“She’s returned.” Mama said it almost victoriously, as if it were as significant a societal achievement as the streetcar lines coming back into service. “And she’s coming here.”