Полная версия

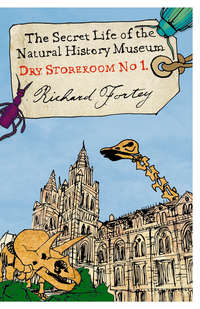

Dry Store Room No. 1: The Secret Life of the Natural History Museum

Taxonomic scientists are often referred to by their speciality. Thus ‘bat man’ would be an expert on bats, ‘worm man’ on worms, and an anthropologist would naturally be a ‘man man’. I suppose I was known as ‘trilobite man’ even though it sounds like a creature from a horror film (‘worm woman’ sounds even worse). Entomologists tend to be even more specific because, as we have noticed, there are just so many insects; a beetle man is, generically, a coleopterist, but he might be a ‘carabid man’ if the Family Carabidae (ground and tiger beetles) was his favourite family. Since there are more than thirty thousand named species of the family there is plenty to know about this particular group, and it is not hard to imagine how somebody could spend their life getting to understand them. The small town I live in has about ten thousand inhabitants, and I am certainly unable to recognize and name more than a small fraction of them. I find it difficult to imagine being on intimate terms with three thousand people, let alone thirty thousand. When a new species is named and described it has to be distinguished from all the others described earlier; and, not surprisingly, mistakes are occasionally made. I once named a trilobite Opipeuter, only to find that the same name had been used a year or two earlier for a South American lizard. It is equally unsurprising that taxonomists tend to be obsessive about what they do. You would have to be to remember the details of so many hairs on so many legs.

Nor are they very well paid. ‘Looking at butterflies all day … it’s not as if it was real work.’ This may partly be a relic from the past. There was a time when to be a museum professional was rather a posh occupation. Private schools were a common background among these elite employees, and probably a private income to match. It was the trade of a gentleman. In those days, perhaps sixty years ago, there was a dress code: suits and ties during the week for the scientific staff. In the Natural History Museum, sports jackets were sanctioned for wearing on Fridays only (by the Director Sir Gavin de Beer) because, after all, this was the day when one went down to the country for the weekend. Later, when one didn’t, the sports jacket became a kind of signature uniform for the museum scientist, complete with leather elbow patches. It indicated an endearing otherworldliness. Too much smartness might betray the wrong priorities, and an inadequate grasp of the carabids. One of my colleagues always wore a marvellously baggy bit of ancient tweed that looked as if it might house a selection of undiscovered species of small organisms. I hope it was curated somewhere upon his retirement, just in case.

Most of the scientists behind the scenes are there because they are devoted to their organisms, like a good priest to his flock. At the present time, there are fewer scientists who exactly correspond to the specialist as I encountered him when I first walked around the Natural History Museum. As we shall see, there are many different kinds of systematic activities today. But it is still true that the taxonomic mission underlies the research programme. In this respect, a museum is different from a university department, where teaching and research run hand in hand, but research does not have to be related to collections. It is the collections that give a museum its signature, its durability, its ultimate purpose.

The Natural History Museum collections were moved from the mother institution in Bloomsbury; the transfer to the splendid new building was completed by August 1883. Richard Owen, he who had looked down upon me during my interview, was the driving force behind setting up an independent place to house natural history collections. He had previously been Superintendent of the Natural History Departments in the original British Museum, and argued that the collections had become too large for a billet among the antiquaries. Owen was a brilliant scientist and scholar, intensely ambitious, sometimes devious, a British pioneer in the study of comparative anatomy, and a guru of the bones. For example, he named the moa from its skeleton. The moa is an extinct flightless bird that walked around New Zealand until the arrival of mankind almost certainly extinguished the feathered giant; the scientific name was Dinornis maximus. Ornis is a bird in Greek, as in the word ornithology; Dino- = terrible as in ‘dinosaur’, ‘terrible lizard’; maximus hardly requires explanation. His judgement rarely faltered when it came to appraising what a sample of bones meant in terms of its closest zoological neighbours. Yet he was no evolutionist. He opposed Darwin vigorously, even after the latter’s theory of evolution had won the day among the intellectual class in the latter half of the nineteenth century. Owen’s vision of a natural history museum was as a kind of paean to the Creator, a magnificent tribute to the glory of his works, a roll call of the splendid species created by His munificence and love for mankind. The words that I used to sing as a child put it thus: ‘All things bright and beautiful, all creatures great and small/all things wise and wonderful, the Lord God made them all.’ The cathedral-like entrance to the great new museum, the nave-like main hall, those columns with their decking of leaves or biological swirls, they all had a message. Here was a temple to nature that was also a shrine to the Ancient of Days.

Owen was an establishment figure par excellence. He knew the Prime Minister William Gladstone very well in the 1860s, and had even been a tutor in natural history for the royal children at Buckingham Palace. No museum figure of modern times has been so close to the seat of power. Owen knew how to make things happen, and his persistent lobbying eventually yielded dividends in the form of Alfred Waterhouse’s vivid new building. Prince Albert, Queen Victoria’s beloved husband, was sympathetic to housing natural history collections in his developing cultural ‘theme park’ in Kensington, and opposite the industrial crafts of the ‘V&A’ along Exhibition Road. The Prince’s effigy, covered in gold, still broods over the Albert Hall a few minutes’ walk north of the Museum on the edge of Kensington Gardens. Owen was trusted to design a museum with sufficient seriousness to satisfy the Victorian sense of self-improvement through knowledge, or as the Keeper of Mineralogy put it in 1880: ‘the awakening of an intelligent interest in the mind of the general visitor’. Owen certainly intended to display in the main hall what he called an ‘index museum’ of the main designs of animals in nature, intended to be a kind of homage to the fecundity and orderliness of the Creator. However, by 1884 when the Museum formally appointed its first Director, William Flower, the principle of evolutionary descent seemed to be the only acceptable way to organize nature for explanatory purposes. The cathedral had been hijacked for secular ends, and the temple of nature had become a celebration of the power of natural rather than supernatural creativity.

Richard Owen in old age with the skeleton he helped to reconstruct of theextinct New Zealand moa, the world’s largest bird.

Richard Owen with moa skeleton. From Richard Owen, Memoirs on the extinct wingless birds of New Zealand. Vol 2. London: John Van Voorst, 1879, plate XCVII.

There are large marble statues of both Charles Darwin and his famous public champion, Thomas Henry Huxley, on display in the Natural History Museum. There is also a bronze of Richard Owen. Few visitors seem to notice them, or pause to read their plaques. Darwin and Huxley look out over a refreshment area on the ground floor, so the great men contemplate a clutter of tables rather than the grandeur of nature.* A seated Darwin is in the splendour of his old age, every inch the bearded patriarch; Huxley, seated nearby, is brooding and imperious. Richard Owen stands around the corner, in academic dress, halfway up the main flight of stairs facing the main entrance. His hands are slightly outstretched, and at least to my eye there is something clerical about him, as if he were offering a blessing rather than a specimen, although his face is still fierce and commanding. The formality and equality of white stone have somehow ironed out the differences between Darwin and Huxley; it is their enquiring spirit that pervades the Museum. They have become the saints in the place. Oddly, the dark bronze of Owen seems more out of place, as if its metallic heaviness were symbolic of the arguments lost to the presiding genius of Darwin, beatified in marble.

It is curious to reflect that the differences that separated these two men, the bronze and the marble, still count today, well over a century later. London is dotted with memorials to its great scientists. Newton is in the Royal Society; Michael Faraday stands outside the Institute of Electrical Engineers on the Embankment. Yet nobody challenges the insights that Faraday or Newton had into the workings of the world (while recognizing, of course, that understanding has also moved on). Yet there are those who would still side with Owen, against Darwin and Huxley, on the subject of biological evolution – they would seek to reverse their respective historical roles and, no doubt, cast out the marble statues. This view is predicated on the idea that evolution is ‘just a theory’; and that other theories – which in fact mean only ‘creation science’ or its close relative ‘intelligent design’ – deserve an equal airing. There are some important and interesting matters hidden away in this argument. There are, indeed, some theoretical issues in evolutionary theory that are still being investigated; indeed, there are whole journals devoted to such questions. Furthermore this is what science is about – probing questions, not just giving ‘the answer’. Physics and chemistry are no different in this regard – they are full of theories in the process of being tested. So are cosmology and economics. But the crux for the statue of Darwin is a third consideration. The issue of ‘creation science’ is not the kind of theoretical question about kin selection that might be found in a scientific journal, it’s about whether evolution happened at all. Put bluntly, it is about whether or not we share a common ancestor with a chimpanzee. The descent of all life through evolutionary processes is not a ‘theory’ in the sense that the creationists would have us believe. So overwhelming is the evidence for evolution by descent that one could say that it is as secure as the fact that the Earth goes around the Sun and not the other way around. Every new discovery about the genome is consistent with evolution having happened. Whether we find it appealing or not is another question, but personally I like being fourth cousin to a mushroom, and having a bonobo as my closest living relative. It makes me feel a real part of the world. So those who promulgate ‘creation science’ are trying to pull off a trick of intellectual legerdemain, a mind jump concealed by jiggery-pokery, mixing in the truly theoretical with what most scientists would simply refer to as the fact of descent. The effect is to try to turn the clock back to a time when immutable versus mutable species was actually a serious debate, a period when Owen and Darwin might have been thought evenly matched for a while. Like Prince Albert, Owen might have finished up gold-plated and Darwin relegated to a back room somewhere in Dry Storeroom No. 1 if only the facts had turned out differently. History has been kinder to Owen than might have been the case. He is recognized as one of the leading anatomists, an outstanding scientific organizer, and instigator of a great museum, even if his dreams for it were transmuted.

The marble statue of Charles Darwin, in wise old age.

Seated statue of Charles Darwin. Photo © Natural History Museum, London.

The hidden rationale behind the displays in any natural history museum I can call to mind is evolutionary, at least as a kind of organizing principle. It does not have to be like that. I can easily imagine an interesting museum in which organisms were arranged by size or colour, or by their utility to mankind. Storage of all the specimens behind the scenes is an entirely different matter, for that has to be systematic. I understand that there is a now a Creation Museum in Kentucky. Its own creators doubtless regard it as a ‘balance’ to all those pesky ‘evolutionary’ museums. It is interesting that the embodiment of respectability for an idea is still a museum, as if a Museum of Falsehoods were a theoretical impossibility. I look forward to a Museum of the Flat Earth, as a counterbalance to all those oblate spheroid enthusiasts.

The Natural History Museum is just one of many in the United Kingdom, and its story could be matched in almost any European country or in North America. The great proliferation of museums in the nineteenth century was a product of the marriage of the exhibition as a way of awakening intelligent interest in the visitor with the growth of collections that was associated with empire and middle-class affluence. Attendance at museums was as much associated with moral improvement as with explanation of the human or natural world. Museums grew up everywhere, as a kind of symbol of seriousness. Universities founded their own reference collections, some of which grew and prospered. Cambridge University has a collection for almost every science department, and Oxford University acquired one of the most beautiful museums of natural history in the world. In some ways, it is a small version of the London museum, but lighter and airier inside, less cathedral, more market place. Large towns needed a museum to celebrate their prosperity, and this period of unrivalled industrial growth meant that there were many new fortunes that sought relief in the purchase of collections. Gentlemen needed ‘cabinets’. An interest in natural history was almost as respectable as an interest in slaughtering wild animals. Our mammal collections show that the two interests were far from incompatible, and that an African or Indian ‘shoot’ could easily become a collection. Scotland was redoubtable in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries as an intellectual centre, so it is no surprise to find that the Hunterian Museum in Glasgow and the Royal Scottish Museum in Edinburgh both have wonderful collections. Wealthy individuals began to realize that a certain kind of immortality could be ensured by endowing collections in their name, and that this was a rather more tangible result than the prospects in the afterlife. One thinks of the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh. The upshot of all this was an explosion in the number of museums paralleling the growth in the numbers of Literary and Philosophical Societies. Nor was this activity confined to the middle classes, as Jonathan Rose has explained in his Intellectual Life of the British Working Classes. No, there was general enthusiasm in most social classes for the life of the mind and the excitement of the new exhibit.

And in the case of Britain this enthusiasm was coupled with the expansion of the Empire. The rights and wrongs have been debated, but it cannot be questioned that the British thought they had both a right and a duty to collect, and then collect some more when abroad in the Empire; and then to send the contents of their collections back home – for keeps. In the eighteenth century, the prospect was for plants of ‘utility and virtue’ as Sir Joseph Banks had said. The market potential was very explicitly built into the purpose of collections. Banks’ collections made on the Captain Cook voyage in Endeavour between 1768 and 1771 were one of the glorious foundation stones on which the Natural History Museum was built. But in the nineteenth century there was an increasing awareness that the study of plants and animals had a value in itself, that indeed there was a duty to inventory the glories and variety of the Empire’s realms; this was an impulse carried forward into the twentieth century, at least until the liberation of the ‘colonies’. Many of the collectors were amateurs in the best sense – intelligent men and women posted to India or Australia, or another of Britain’s many dominions, with time enough to make collections. This was no doubt motivated in some expatriates by the need to alleviate the boredom of duties carried out far from home; others may have made natural history collecting part of a wider programme of exploration. Terrestrial snails were sent to the Natural History Museum by the splendidly named Henry Haversham Godwin-Austen from India, where, among other things, he surveyed the world’s second highest mountain, K2 or Mount Godwin-Austen. Many collectors were talented artists, and women, in particular, were often trained in the skills of watercolour painting. Colours in life could be accurately recorded, even if the collecting process dimmed the original. Then, too, the postal system of the Empire was very efficient, so that collectors could receive encouragement and requests for more specimens from the appropriate Keeper or curator at a museum. From some parts of the world, such as Burma, it was easier to communicate then than it is now.

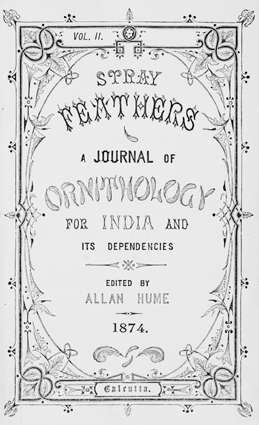

Many private collections made by moneyed individuals eventually found their way into the national collections by bequest or donation. I might mention as one example the collection of Allan Octavian Hume from the Indian Empire acquired in 1885, with 63,000 bird skins, 19,000 eggs and, as an afterthought, 371 mammals. Or there is the famous Lepidoptera (butterfly and moth) collection, comprising some hundred thousand specimens, left as a bequest by Edward Meyrick in 1938, the product of his lifetime’s learning and publication. Some collections were purchased; Hugh Cuming’s collection of shells was bought in 1866 for the appreciable sum for the time of £6,000, and a special grant was made from Parliament to buy it. It comprised 82,992 specimens. That is more than a dozen for a pound, which actually sounds quite reasonable. Overall, the collections grew apace, mostly filling up those cabinets behind the scenes, so that the general public would have been unaware of the increase. In terms of sheer numbers, the entomologists always win. According to William T. Stearn the insect collections had grown from 2,250,000 specimens in 1912 to some 22,500,000 in 1980. For the whole Natural History Museum, the latest figure is eighty million specimens. Such a number is quite incomprehensible as a quantity. Who could say if a huge pile of wheat in front of them comprised a million, ten million or eighty million grains? We simply do not see large numbers that precisely. Perhaps the more meaningful image is that of the ranges of drawers I saw stretching away into the distance when I explored the far reaches of the Entomology Department all those years ago. There was a vision of the scale of life, shelves and shelves of it, stretching away apparently for ever. That is the extent of our responsibilities.

Making known the zoological treasures of Empire: the cover of Allan Octavian Hume’s journal Stray Feathers.

Title page of Stray Feathers, A Journal of Ornithology for India and its Dependencies, Allan Octavian Hume, Vol. 2, (1874).

One of the few things one can admire about the British Empire was its propensity to make museums and botanical gardens. A few years ago, I visited the Indian Museum in Calcutta, another huge and serious building in which the artefacts of the subcontinent were housed. The old Indian Geological Survey was nearby, and there were preserved trilobite specimens collected at the end of the nineteenth century, still in their original cardboard boxes. It was as if the whole place had been preserved perfectly since the British left, a kind of fossilized museum. The curation system still worked, although the twenty-first century had yet to impact on the organization. The same old typewriters were still at the deal desks as they had been in 1947. A clerk arrived at 10 a.m. every day and dusted them off with a feather duster, and then proceeded to do little visible work for the rest of the day. Flies buzzed in the sleepy heat of the afternoon. In the same city was a Botanical Garden, magnificent in decay. The old pavilions had literally gone to seed. Once formal flowerbeds were now overrun with native creepers. It was sad to see a system that had once worked so well fallen into desuetude. There were even snakes in the grass. The banyan tree had grown into the biggest in the world, or so it was claimed, with its many branches propped up by the columns of its aerial roots, so that this wholly natural structure looked like the great mosque of the Mesquite in Córdoba. I hope that when India becomes rich on its own account a little money will be spared to restore the Calcutta Botanical Garden. I had seen its well-cared-for equivalents in Christchurch, New Zealand (see colour plate 4), and in Sydney, Australia, both now grown to splendid maturity, and both worthy heirs to Kew Gardens in London. I like the thought of early colonists listing the creation of a botanical garden and museum as one of the earliest necessities, a badge of civilization. One could argue that this particular idea still has currency, even if many of the other colonial ideals have not withstood the scrutiny of history. It certainly indicates that the nineteenth-century administrators took plants and collections seriously. It is of a piece with the growth of museums and civic gardens in nearly every big town in the home country, and with the great exercise in the systematization of nature that prompted all those earnest contributions to the collections of the Natural History Museum in London, and its equivalents around the world. Nature must evidently be known and named, no less than its beauty appreciated.

Perhaps those colonial pioneers dreamed that the biological world would be described before the dawn of the twentieth century. If so, their dream went unfulfilled; that century came and went and still the inventory of nature was far from complete. I have mentioned already how the labour of making all the species known is still in progress in the twenty-first century. It will not be completed at the end of it, because of the sheer size of the task. We shall see below how modern molecular techniques might provide a shorthand way of speeding up identification. The problem now has an added urgency because of the changes, mostly destructive, that mankind is foisting on the environment. Who can predict whether whole ecosystems will be pushed to extinction as a result of global warming? There are so many species out there that have never been named and described, like those I mentioned in the deep sea. The Times reported on 27 June 2006 that an average of three new species of animals and/or plants had been discovered in Borneo for every month of the preceding decade – and this in a part of the world where forest has been reduced by 25 per cent since the mid-1980s. Every species on Earth has a biography and each one is fascinating in its own way. There may be biologies in the deep sea about which we know nothing. Some of them may be useful to mankind in medicine, or in dealing with extreme conditions as we begin to stretch our metaphorical legs to climb to the stars. Who knows? If we allow species to disappear before they have a chance to tell us about themselves it will be a tragedy to add to the many that our species has already inflicted on the world. The first stage towards understanding is naming – to recognize that this creature before us is different from another already known. I believe we do not have a moral right to imperil the continuation of any species. Who are we, one species among so many, to obliterate the work of millions of years of evolution? Are we like the Greek gods acting on whimsy? Unfortunately, it is difficult to persuade everybody of this moral position. It appears on few political manifestos, except as a kind of harmless truism, vaguely akin to ‘we must be kind to pretty furry things’. It is so much more important than that. I don’t want the only record of a species to be on a video archive, or one of those gloomy, pallid faces peering out of a jar in the Spirit Collections.