Полная версия

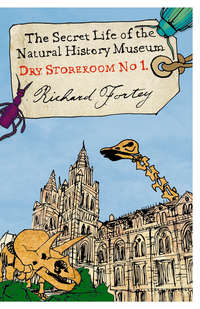

Dry Store Room No. 1: The Secret Life of the Natural History Museum

To either side of the ‘nave’ of the Herbarium there were aisles in which worked the botanists. To be more accurate, the arrangement was like a series of private chapels, tucked away on either side of the long hall. There were no doors to separate the workrooms from the main part of the Herbarium, but rather a narrow opening led into a concealed office area, hidden behind the flanking cabinets, a secret niche protected from the prying eyes of the casual visitor. Nowadays, these niches are partly occupied by computers, but when I first visited there were old black typewriters sitting on the desks, and piles of papers and sheaves of carbon paper for making copies for the files. Old monographs lay open at pictures of weeds. The niches did have a Dickensian atmosphere, and one half expected a Sam Weller to pop out from his niche and cry out that he was ‘wery sorry to keep you waiting, sir’. On my exploratory trip into the Herbarium, I was foolish enough to poke my head around the corner of a niche belonging to a very cross-looking senior curator, who threw a kind of generalized snarl in my direction. I decided it was time to flee back to the safety of the trilobites.

Later, I took another trip out through the basement, but this time I popped out of the back of the old building into a kind of alley; this was the ‘tradesman’s entrance’ to the Museum, where bicycles were parked, and pallets and unwanted pieces of furniture were piled up. There was often a funny smell (see p. 149). Many pieces of surplus wood or furniture had the words ‘Rosen wanted’ scrawled upon them in white chalk. I subsequently discovered these rejects had been bagged by Brian Rosen, the coral expert. Because his room commanded a view of the alley he could nip out with his chalk quicker than anybody else. When I got to know Brian better I visited his house in south London and found complex constructions in his garden entirely fabricated from Museum detritus. There was a kind of apotheosis of the garden shed, a thing with porticoes and pillars, and inside the shed yet more stuff retrieved from the clutches of the skip. I have a vision of a Watts Tower one day rising from the back streets of West Norwood, entirely composed of bits and pieces discarded from the Natural History Museum. Today, the back alley by the bikes is where smokers go to puff furtively, just as they did in their school days.

At the further end of the passageway, an intriguing notice: ‘Spirit Building’ pointed the visitor to a newer block than the original Museum, entirely undistinguished from the outside, no ornament at all. This building proved to be another part of the Zoology Department. The spirits lived in jars. These were the wet collections: pickled, preserved and potted zoology. The store rooms were dark and sealed off from the world, so that when a light was switched on a battery of round glass jars with similar lids stretching away into the distance would suddenly be illuminated … and inside the jars maybe a huge python curled up and pallid, like the intestine of a giant, or perhaps a fish all spiny and phantasmagorical, or a lizard that seemed to paw the edge of its jar, or a long-dead lobster. There were several floors of these jars, arranged by zoological kind, cupboard after cupboard full of fishes, or crustaceans, or frogs, or lizards. It was like a store room for warlocks, where eye of newt and toe of frog came in a thousand varieties, and fillet of fenny snake was as easy to order as buttered toast.

The specimens were preserved in alcohol or formaldehyde. Colour seldom survived this treatment for long, so that fish and newt, frog and worm, jellyfish and jeroboam, shared a kind of tuberous pallor, something like that of a parsnip. The jars ranged in size from tiny phials crowded together and containing dozens of small shrimps to great towers of glass holding goannas from the outback or carnivorous lizards from Comoro. Here was the profusion of the animal world pickled in perpetuity, a washed-out parade of the panoply of life. It was a place to make one think of the transience of all things. I had never realized until I slid open one of the cupboards in the Spirit Building that many fish have a naturally depressed appearance. A grouper in a jar is a sorry thing indeed, the corners of its mouth turned down in a parody of gloominess. Worst of all is the stonefish, an immensely ugly animal that lurks in estuaries in Australia. It is stout, and covered in warty excrescences, with fins more like props than agents of propulsion; its mouth is gloomier than a grouper’s; it seems to have plenty to be gloomy about, looking as it does. I discovered that it spends most of its life camouflaged and motionless, its ragged skin a perfect disguise, until some prey comes near enough – then that apparently dejected mouth can engulf the unfortunate prey in a trice.

On another expedition I encountered the General Library (and this is just one of five libraries in the Museum), after entering it accidentally by a side door off one of the public galleries. It was difficult to believe that there could be so many books pertaining to natural history. Situated in a newer part of the Museum, the main reading room was vast, with tomes on shelves all around the perimeter stretching as high as one could reach – and beyond this room there were galleries of further books, and here they were piled so high on shelf after shelf that there were little ladders to help the reader retrieve some of the higher volumes. There are those who find libraries intimidating, but I am not one of them. I like to see the books in their old leather bindings, the shelves stretching away, deeply filled; it gives me a sense of continuity with past scholars. Even so, encountering an enormous library like this for the first time is a humbling experience. Think of all the thousands of workers putting pen to paper to add to the knowledge of the natural world, or to communicate scientific ideas to their colleagues. If all this is known already, how can a new intruder into the world of learning make any mark at all?

I took down one of the volumes at random: Acta Universitatis Lundensis – the scholarly publications of the University of Lund in Sweden. Well over a century of labours by Scandinavian scientists were preserved here in perpetuity, in volume after volume, or at least until paper crumbles away. The older volumes had green leather bindings, scuffed with use and age; newer volumes were cloth-bound – doubtless in the interests of economy. This part of the library was devoted just to Scandinavian journals, for nearby was a huge run of the organ of the Royal Society of Sweden some yards in length, and over there a great swathe of journals from the University of Uppsala, one of the most ancient universities in Europe. In these pages the great Linnaeus published some of his work, which is still cited today. So it went on, with publications from universities and institutes in Sweden and Norway that meant little to me then. And if the works in this segment of the library were just from one little piece of the world how much greater would be the literature of the United States, or Russia? Or China? The Museum was dedicated to trying to collect everything that was published on the natural history of the planet. Once more I attempted in vain to calculate the size of the holdings on the shelves, floor on floor, only to boggle hopelessly, baffled by bibliographic boundlessness. I crept back to my own little corner.

So my exploration continued, up dark stairwells and down dim passages. I came across a room full of antelope and deer trophies, the walls lined with dozens of ribbed or twisted horns, as if it were the entrance lobby to some stately home owned by a bloodthirsty monomaniac. On another occasion I found my way into one of the towers that flanked the main entrance to the Museum – only to find that to get there one had to take a path that led over the roof. I came across a taxidermist’s lair, where a man with an eye patch was reconstructing a badger. I failed to find the Department of Mineralogy altogether, apart from meeting some meteorite experts in their redoubt at the end of the minerals gallery. There seemed to be no end to it. Even now, after more than thirty years of exploration, there are corners I have never visited. It was a place like Mervyn Peake’s rambling palace of Gormenghast, labyrinthine and almost endless, where some forgotten specialist might be secreted in a room so hard to find that his very existence might be called into question. I felt that somebody might go quietly mad in a distant compartment and never be called to account. I was to discover that this was no less than the truth.

The geography has changed profoundly since I first entered the British Museum (Natural History). Science departments have been rehoused – my own department, Palaeontology, being the first of them. I had to say goodbye to my polished cabinets, balconies and nineteenth-century haven to relocate to the third floor of the rather characterless modern block tacked on to the eastern end of the old building, an extension as typical of the utilitarian (some might say cheap) 1970s as the old building had been typical of the Victorian love of detail. The relevant minister, Shirley Williams, opened the new wing in 1977. Moreover, the space was generous, and necessary, because the palaeontologists had formerly been dotted all over the place; now they could be together. The Zoology Department, including all those sad fish, has been moved to the much more glamorous Darwin Centre at the western end of the building. Farewell to the Spirit Building, and to its dusty and slightly romantic gloom. Only my old friends the molluscophiles are still secreted in their old haunts in the basement. Nonetheless, the sense of the three-dimensional maze has not been lost. The whole thing just got bigger. Gormenghast lives on.

On one of my forays through the basement I came across a door that I had not noticed before. This was on a corridor with an air of being seldom visited on one side of which were tucked away the osteology collections – bones, dry bones, where oxen strode naked of their skin and muscles, and great bony cradles hung from the ceiling, the jawbones of whales. Here, ape and kangaroo met on equal terms in the demotic of their skeletons, with no place for the airs and graces of the flesh. Strange though these collections might seem, they were as nothing compared with what lay behind the mysterious door opposite. For this was Dry Store Room No. 1. Neglected and apparently forgotten, this huge square room entombed the most motley collection of desiccated specimens. Fishes in cases were lined up species by species in their stuffed skins; they were presented in faded ranks like a parade that had forgotten the bunting. At one end there was a giant fish that seemed to have been cut off mid-length, such that the posterior part of its body was apparently missing, and it had a silly little mouth out of proportion to its fat body. It was a sunfish, and its cut-off appearance was entirely natural – a faded notice attached to it proclaimed it was the ‘type’. Elsewhere there were odd boxes, one of which contained human remains, laid out in a kind of slatted coffin. The shells of a few giant tortoises hunkered down like geological features on the floor. There were sea urchin shells, and some skins or pelts of things I couldn’t identify. Most peculiar of all, on top of a glass-fronted cupboard there was a series of models of human heads. They were arranged left to right, portraying a graded array of racial stereotypes. One did not have to look at them for very long to realize that there was a kind of chain running from a Negroid caricature on one side to a rather idealized Aryan type on the other. This was a remnant of an old exhibit, heaven knows from what era, with more than a sniff of racism about it. Dry Store Room No. 1 was a kind of miscellaneous repository, a place of institutional amnesia. It was rumoured that it was also the site of trysts, although love in the shadow of the sunfish must have been needy rather than romantic. Certainly, it was a place unlikely to be disturbed until it was dismantled. I could not suppress the thought that the store room was like the inside of my head, presenting a physical analogy for the jumbled lumber-room of memory. Not everything there was entirely respectable; but, even if tucked out of sight like suppressed memories, these collections could never be thrown away. This book opens a few cupboards, sifts through a few drawers. A life accumulates a collection: of people, work and perplexities. We are all our own curators.

2

The naming of names

In 1976 I almost burnt down the Smithsonian Institution in Washington. If I had succeeded I imagine that I would now be one of the most famous scientists in the world. Thirty years ago I was a pipe smoker, and the study cubicles in the National Museum of Natural History in the Smithsonian allowed scholars to puff away at their pipes while looking down the microscope. It somehow seemed an appropriate thing to permit. Behind the scenes at the Smithsonian lies a similarly vast labyrinth to that in our Natural History Museum and here, too, are ranks of collections, quietly minding their own business until a visiting expert re-examines them in their labelled drawers. I was interested in looking at trilobite specimens collected years before by one of their staff, E. O. Ulrich. I had my microscope in front of me, and a line of specimens to one hand, while the other picked up the pipe from time to time, and waved it about. It was about as contented a scene as could be imagined. At the end of the day I did what pipe smokers do, which is to tap out the dead pipe into the metal waste-paper bin in the corner of the room. The only problem was that the pipe was not completely dead; I had deposited smouldering scraps of Erinmore Mixture among the discarded pieces of paper in the bin. I shut up for the night and went home. Half an hour later, a passing security man noticed billowing smoke arising from my cubicle; fortunately, the fire was quickly extinguished. It might have been a different story had the receptacle been a woven basket. I overheard mumbled gossip about me for the next few days.

Had I destroyed the United States’ national collections of natural history the damage would have been irreparable, not just for the USA but for the world. The most important single feature of the great collections is that they form the basis for naming the living world. They are the reference system for nature. The curated specimens are the ground truth for the scientific names of animals, plants and minerals. The naming of organisms is called taxonomy, and their arrangement in classificatory order is called systematics. All those cabinets I passed when I explored the Natural History Museum in London were the storehouses for the still-growing catalogue of what is now often termed biodiversity, the richness of the living world. Although it achieves a lot besides, the basic justification of research in the reference collections of natural history museums is taxonomic. So if my Erinmore Mixture had sparked off a major conflagration much of the basis for the names given to fauna and flora around the world would have gone up in smoke. It would have taken years to sort out. Some museums were bombed during the Second World War, such as the Humboldt Museum in Berlin, and lost many specimens; the resulting taxonomic confusion is still being worked out. That is why museums place such emphasis on the security of their collections; it is an acknowledgement of their permanence: hence the special keys and the security codes.

The taxonomic mission can be briefly stated: to make known all the species on Earth. It sounds easy. This is, of course, only the beginning of finding out about life, because there lies beyond identification so much more, such as how animals live – their ecology – or why there are different species in different parts of the world. Often the taxonomy is inextricably entwined with these other aspects, for example, when two closely related species may be distinguished by having subtly different ecology. European ornithologists will know the instance of the exceedingly similar marsh (Parus montanus) and willow (Parus palustris) tits, which are readily distinguishable only by their songs. Recognition of species is always the first step in understanding the complex interactions of the biological world. Just as you need a vocabulary before you can speak a language, so it is necessary to have a dictionary of species before you can read the complex book of nature.

Nor is the taxonomic mission as simple as it sounds. There are a few groups of organisms – birds and mammals come to mind – where large size and intensive study over many years means that the vast majority of species have been named and described. Even here there can be surprises, as when a new species of large ungulate mammal was discovered in the jungles of Vietnam a few years ago, or when in 2005 a pristine part of New Guinea was explored for the first time and a rare bird of paradise brought ‘back from the dead’. Bats are turning out to have many more species than was originally thought. I went with a research student into the cloud forest of Ecuador to see a new bat species with the longest tongue in the world that had apparently evolved to feed from (and pollinate) an extraordinary flower with a matching long corolla. It is illustrated in the colour plates. But as a rule there are very few new mammal or bird species to discover, and global concern is rather with conserving those that are known already: by any standard this is a big enough matter.

With other groups of organisms the story is different. The insects are the most obvious example: small, teeming and unnoticed they fill almost every habitat on earth. I will choose one example, from a cast of thousands. You have to be a special kind of person to love fungus gnats, but if you look at mushrooms growing in woods you will certainly see these tiny insects flying around the fungi. They are abundant. Most of us encounter these particular creatures as irritating ‘wormholes’ occupied by their larvae that might spoil an otherwise nice-looking field mushroom. But they still fulfil an important function in nature, and they provide a foodstuff for insectivores in their turn. They are a link in the chain. But how many species are there? And how do you tell them apart? Do they feed on lots of different fungi or are there specialists for particular kinds of fungi? All these questions require the attention of a knowledgeable taxonomist, a microscope, and skill. Tiny differences in the wings or the hairs on the legs may be crucial in the identification of a species. With luck, expertly identified specimens will finish up as collections in a cabinet marked Family Mycetophilidae (‘mushroom lover’) in the Natural History Museum. As to how many species there are, well, at the last count there were 531 different fungus gnats in the United Kingdom alone, and more being added all the time. It is scarcely surprising that there are many more species still remaining to be discovered in the wild. If a new bat can be discovered in Ecuador’s cloud forest, it is likely that nobody has even looked at the fungus gnats. And each species will have its own ecological story to tell, another biography to add to the narrative of the natural world. When it comes to status as a species, size doesn’t really matter.

A fungus gnat, Mycetophila, perched on a fly agaric.

Fungus gnat Mycetophila. Photo © Andrew Darrington/Alamy.

At this point one is supposed to put the beetles centre stage, because what is true of the fungus gnats is true of beetles many times over. The geneticist J. B. S. Haldane remarked, when questioned by a cleric about the putative properties of God, that one sure characteristic of the Almighty would be ‘an inordinate fondness for beetles’; this has become one of biology’s well-worn phrases. It is no less appropriate for all its familiarity. One-fifth of all species are probably beetles, most of them leading inconspicuous lives. There are somewhat less than half a million species of these animals named so far. When in the 1980s Nigel Stork collected insect species from the tropical forest canopy, he found that many of them had never been collected before – and that many of them were beetles. These were new species, needing a scientific name. It is a massive task just to make an inventory of beetles, let alone understand their biology.

Outside the insects, we can go on to tiny organisms like nematode worms, or smaller still to single-celled organisms – a whole universe of different biological organisations – or down to the smallest of all, the bacteria, where it may be necessary to use biochemistry or genetics to recognize species for what they are. Or we might go down into the depths of the sea where a start to sampling has hardly been made, and every animal is a specialist adapted to eternal darkness and great pressure. Nobody knows how many undiscovered species there are down there, although it is certain that there are many: a single trawl can reveal a dozen new crustaceans. A 2007 report from the Antarctic revealed many extraordinary new crustaceans that had escaped the attention of all marine biologists. There are huge numbers of unknown fungi – tiny ones many of them, or inconspicuous species hidden away under rotting logs. Something like two million species have been named and recognized, and there are certainly an equal number still to name. Many scientists believe that there may be five times that number, considering the habitats that are still so poorly known. There is so much to do, and so few people to do it. An estimate of the number of people who might know about systematics in the whole world came to only about four thousand. And I have not even mentioned fossils: a history of life also needs the myriad characters in the narrative of extinct animals and plants to be identified. So far, there is no indication that we are anywhere near the end of that process, even regarding the largest animal fossils, such as dinosaurs. The labyrinthine anatomy of the Natural History Museum might after all be appropriate to the world it represents, for the realm of nature is truly a castle of Gormenghast, with its half-explored wings, and obscure corners where few venture.

Many of the people whose names I had noticed on their offices or cubicles were soldiers in this war against ignorance. They were unseen heroes in a battle against insuperable odds, a battle unnoticed by the million people who pass through the public galleries. A lifetime of endeavour in these cells might be rewarded with the accolade of becoming an ‘authority’ – even a ‘world authority’. This means that the scientist and scholar knows as much about his chosen area as anyone – his views will be sought out on the identification of his organisms by scientists in Minneapolis, Manchester or Mombasa, be they beetles or bats. The notion of authority is a curious one. It is not something that one says of oneself, so I have never heard anyone introducing themselves as ‘the authority on mushroom gnats’. On the other hand it is quite often used to describe a fellow scientist: ‘Dr Buggins, the authority on toads’ and so on. Just working in a museum like the Musée d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris or the American Museum of Natural History in New York is no guarantee of becoming an authority. This distinctive label is hard earned by publishing and writing on the chosen subject, although it would be difficult to define a kind of critical mass of words when a young scientist passes into an authority. There is certainly no sex discrimination in the title these days, as there would have been a hundred years ago. It is one of those titles that cannot be bought, nor traded, nor given away; it just arrives, like grey hair.